Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to clarify the microlevel determinants of the economic burden of dementia care at home in Japanese community settings by classifying them into subgroups of factors related to people with dementia and their caregivers.

Design

A cross-sectional online survey.

Participants

4313 panels of Japanese research company who fulfilled the following criteria: (1) aged 30 years or older, (2) non-professional caregiver of someone with dementia, (3) caring for only one person with dementia and (4) having no conflicts of interest with advertising or marketing research entities.

Primary outcome measures

Informal care costs and out-of-pocket payments for long-term care (LTC) services.

Results

From 4313 respondents, only 1383 caregivers in community-settings were included in this analysis. We conducted a χ² automatic interaction detection analysis to identify the factors related to each cost (informal care costs and out-of-pocket payments for LTC services) divided into subcategories. In the resultant classifications, informal care cost was mainly related to caregivers’ employment status. When caregivers acquired family care leave, informal care costs were the highest. On the other hand, out-of-pocket payments for LTC were related to care-need levels and family economic status. Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living functions such as bathing, toileting and cleaning were related to all costs.

Conclusion

This study clarified the difference in dementia care costs between classified subgroups by considering the combination of the situations of both people with dementia and their caregivers. Informal care costs were related to caregivers’ employment and cohabitation status rather to the situations of people with dementia. On the other hand, out-of-pocket payments for LTC services were related to care-need levels and family economic status. These classifications will be useful in understanding which situation represents a greater economic burden and helpful in improving the sustainability of the dementia care system in Japan.

Keywords: informal care, rud, cost, classification, Japan

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study clarified the difference in dementia care costs between classified subgroups by considering the combination of the situations of both people with dementia and their caregivers.

The χ² automatic interaction detection dendograms provide a visual depiction of criteria and predictor variable interactions that might not be detected in traditional analytic procedures.

The sample may therefore not be representative of all caregivers because the sample is limited to those who have access to the internet and are registered with an internet research company.

We only assessed objective burden of dementia care such as informal care time or costs, but we did not consider the subjective burden of care and depressive symptoms.

Introduction

In the ageing society of Japan, it is estimated that there are approximately 4.7 million people living with dementia and that there will be approximately 7 million people with dementia in 2025.1 Given that it is also estimated that the total number of people with dementia throughout the world will double every 20 years,2 we need to reconsider how to prepare for dementia care in the community.

Long-term care (LTC) services in Japan used by people with dementia in home care can be classified into three main types: (1) LTC insurance services, (3) LTC services not covered by insurance and (3) informal care as mutual assistance by family members. When a person with dementia uses the LTC insurance service, the user bears 10% or 20% of the service expenses as out-of-pocket payments depending on the person’s income (Article 49–2 of the Long-Term Care Insurance Act). Aside from such copayments, when LTC services not covered by insurance or exceeding the LTC insurance limit amount are used, people must pay the full amount. Furthermore, it has been pointed out that informal care is an important component of home care, yet it places a burden on caregivers.3 4 Nevertheless, given the estimates of the societal costs of dementia care throughout the world, the impact of informal care is essential.5 6

The Japanese government recommends policies to shift to patient-centred and home-centred care to reduce the fiscal burden of the insurance system on community-based integrated systems. While microlevel of impact of dementia care has not been insufficiently understood,7 to construct a sustainable dementia care system, we clarified the personal economic burden of dementia care for different residence types and demonstrated that the cost at home in a community setting was equal to or higher than in various institutions.8 Sustainable dementia care systems should be provided to benefit the government or insurance system and also to benefit people with dementia and their caregivers. Furthermore, although there are increasing dementia care costs related to the severity of dementia,9–12 it can be seen that the cost of dementia care increases through the interaction of characteristics or situations of people with dementia and their caregivers. Given this interaction, it is necessary to understand the actual conditions by classifying cases where the greatest economic burdens in dementia care are felt.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to clarify the microlevel determinants of the economic burden of dementia care at home in community settings by classifying them into subgroups of factors related to people with dementia and their caregivers.

Methods

This study was a cross-sectional study, based on a self-rated, online questionnaire survey. The economic burden of dementia care in this study is roughly divided into informal care costs as opportunity costs and out-of-pocket payments that people actually made.

Online survey for data collection on people with dementia and their caregivers

In this cross-sectional study, we conducted an online questionnaire survey from 3 March to 14 March 2016 in cooperation with a commercial research company (Automatic Internet Research System, Macromill, Japan). Potential participants fulfilled the following criteria: (1) aged 30 years or older, (2) non-professional caregiver of someone with dementia, (3) caring for only one person with dementia and (4) having no conflicts of interest with advertising or marketing research entities. A total of 3600 participants were recruited from the research company’s registrants and divided into different age groups (850 participants each in the groups aged in 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s; 200 participants in the group aged ≥70 years). We excluded caregivers under 29 years of age because, in Japan, they are estimated to represent only 2% of all caregivers.13

Questionnaire

Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD)14 15 is a widely used tool to collect data about resource use in persons with dementia and their caregivers.15 RUD is available in more than 60 languages and it is widely used throughout the world. In this study, we used RUD (Japanese version) items related to the characteristics of people with dementia and their caregivers, informal care time, employed situation of caregivers, residential types of people with dementia and resource use of nursing care services. We added items related to LTC services and residential types. The questionnaire components were divided into four categories: (1) characteristics of people with dementia, (2) caregivers’ situations (eg, employment and cohabitation status), (3) informal care duration and (4) frequency of utilisation of LTC services.

In this project, we could not get information about severity of dementia data because it was regarded as too difficult for caregivers to estimate that. However, we asked for substantial information about care-need levels. Care needs reflect function, which is a stronger explanatory factor for costs than cognition.16 Care-need levels (Support-need levels 1–2, Care-need levels 1–5) determine whether a person is qualified to apply for LTC insurance (Article 27 and 32 of the Long-Term Care Insurance Act). Once an insured person applies to use any LTC service, their mental and physical status is first assessed by certified researchers using a basic checklist. Based on this checklist, care-need times are estimated using an evidence-based computer algorithm. This algorithm was created from the data on how much LTC services were required in 48 hours for more than 3000 elderly people as a 1 min time study.17 After estimating the care-needs time, care-need levels were determined by an expert panel to indicate the amount of care required by each person while taking into consideration their symptoms and functional capability. High care-need levels indicate increasing dependency and requirement for LTC services.18 Care-need levels also affect the base amount of the maximum payment for LTC services allowance categories covered by insurance.

Informal care time

In the questionnaire, informal care time was divided into three domains; support for Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) and Supervision.15 We asked for the mean caregiving time per day and mean caregiving days per week in the past 30 days. We then multiplied the mean daily caregiving time and caregiving days per week to calculate both weekly and monthly informal care time. Supervision time was excluded in calculating informal care time and costs because supervision could be done simultaneously when caregiving for ADL and IADL functions or in other housekeeping for people without dementia and other family members.

Cost estimation

In this study, we identified three costs as follows: informal care costs, out-of-pocket payments for LTC services covered by insurance (copayments) and out-of-pocket payments for LTC services not covered by insurance. To calculate the informal care costs, there are two methods that are frequently used: the ‘opportunity cost’ and ‘replacement cost’ approaches.19–21 With the opportunity cost approach, it is assumed that there is an alternative use of caregiving time (such as paid work) and thus estimates the costs due to this lost opportunity, whereas the replacement cost approach assumes that informal care services can be valued similarly to home care services provided by professional caregivers. Even though many previous studies on the economic valuation of informal care have used the replacement cost approach,20 the ‘opportunity cost approach’ is recommended by the developers of RUD for estimating informal care costs.2 5 22 We used the opportunity cost approach to assess informal care time as forgone wages for caregivers.2 5 9 We used caregivers’ monthly mean wages stratified by sex and age to value informal care. We assessed informal care costs for caregivers who were not working or who were over 65 years of age at 30% of the mean wage of employed caregivers.23–26 A maximum daily informal care time of 16 hours was assumed, in order to allow for other activities such as cooking for other family members and sleep.12 27 28 Caregivers were asked to state their contribution to the total informal care in 5-point scale of 20%. In order to treat all caregivers as primary caregivers and estimate the costs associated with all informal care provided to a patient, we adjusted the informal care time by dividing its time by the median of these contribution levels, according to RUD instructions. This adjustment of informal care time was done only when calculating the informal care costs.

Out-of-pocket payments for LTC services both covered and not covered by insurance were included in the questionnaire. We asked for these out-of-pocket payments through categories that were easy to answer (no payments, under JPY9999, JPY10 000–24 999, JPY25 000–49 999, JPY50 000–74 999, JPY75 000–99 999, JPY100 000–124 999, JPY125 000–149 999, JPY150 000–299 999, JPY300 000–499 999 and over JPY500 000). We adjusted the answers by capping the upper limit of the limit amount (Care-needs level 1; JPY166 920, Care-needs level 5; JPY 360 650) depending on each care-needs level or each ratio of copayment (10% or 20%) if the answers were over it. These costs were substituted by a median of each category, and we calculated the weighted average as the following formula: .

All costs were converted from Japanese yen to US dollars using the purchasing power parity rate in 2016 (\102=$1) provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

With respondents, we only focused on community settings for people with dementia who lived in their own home. We excluded respondents based on the following criteria: (1) people with dementia who were hospitalised or lived in nursing home, (2) lack of data about out-of-pocket payments for LTC services or care-need levels, (3) contradictions in relationships between caregivers and people with dementia and (4) contradictions in care time (over 24 hours). When the age difference was less than 15 years and the person with dementia was a parent or child (not in-law), these cases were identified as contradictions.

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive analysis for characteristics of people with dementia and caregivers. We then stratified the informal care time and dementia care costs by the care-needs level and cohabitation to test our hypothesis that high care-needs level or people who live with caregivers need more informal care time. In this description, we did not adjust informal care time by caregivers’ contribution rate.

Also, we used χ² automatic interaction detection (CHAID) analysis to identify the characteristics of people with dementia and caregivers who needed more care services. In CHAID analysis, the dependent variable would be divided into subgroups by the most explanatory independent variables. These groups could be formed by any possible combination with all independent variables. In particular, we conducted an exhaustive CHAID analysis that repeats the trial until it finds the optimal combination of all independent variables. The CHAID dendograms provide a visual depiction of criteria and predictor variable interactions that might not be detected in traditional analytic procedures. We set informal care costs, out-of-pocket payments for LTC services covered by insurance and out-of-pocket payments for LTC services not covered by insurance as dependent variables. Then, we used the characteristics of people with dementia (age, sex, care-need level, dementia types, ADL and IADL functions and primary disease as the reason for care), the characteristics of caregivers (age, sex, marital status, children, cohabitation with people with dementia, visiting time, relationship to people with dementia and occupation) and economic factors (the ratio of copayments for healthcare services and family income of caregivers). We treated the ratio of copayments for healthcare services as income proxy variable because this ratio was decided by income of people with dementia. We set the following criteria: tree depth was limited to three levels, no group smaller than 100 was split, no group smaller than 30 was formed, and the p value for all statistical tests was under 0.05.

All data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Ethical considerations and consents

This study was approved by the Ethics committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (R0487). All participants were volunteers and they were informed that there was no obligation to participate in the study, and only people who consented to this study completed the questionnaire.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not formally involved in this study; however, their caregivers participated in our online-based questionnaire survey. Caregivers, who constituted the online panel, were sent the invitation by the internet research company. Patients and their caregivers can view the results of this study when it is published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Results

Characteristics of people with dementia and their caregivers

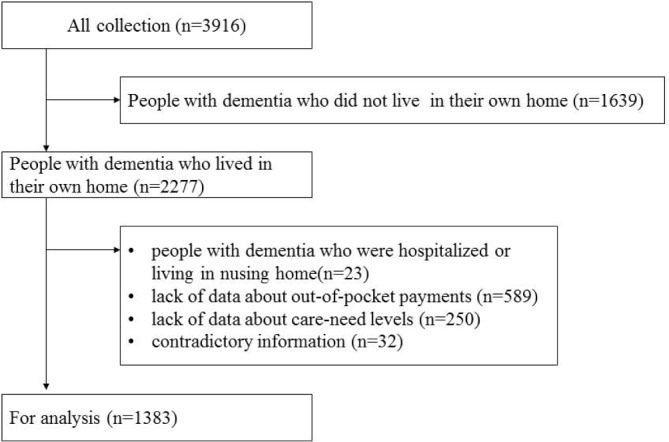

A total of 3916 caregivers answered the questionnaire. We focused only on people with dementia who lived in their own home (n=2277). However, we excluded the data according to the criteria and the final sample comprised 1383 respondents (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection process for the analysis. This diagram shows the flow of participants who we focused on.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of people with dementia and their caregivers. More than half of the people with dementia were female (66.7%), and the mean age was 81.8 years. In contrast, more than half of the caregivers were male (61.7%) and the mean age was 52.2 years. 1233 people (89.2%) responded that ADL functions such as meals and toilet use could be managed by themselves, while IADL functions such as cleaning and shopping could be done by one person in the same way. There were only 788 people (57.0%) who did the latter by themselves.

Table 1.

Characteristics of people with dementia and caregivers

| People with dementia | n=1383 |

| Age, mean±SD, years | 81.8±10.3 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 922 (66.7) |

| Male | 461 (33.3) |

| Care-need levels, n (%) | |

| Support-need levels 1–2 | 253 (18.3) |

| Care-needs level 1 | 310 (22.4) |

| Care-needs level 2 | 335 (24.2) |

| Care-needs level 3 | 258 (18.7) |

| Care-needs level 4 | 122 (8.8) |

| Care-needs level 5 | 105 (7.6) |

| ADL/IADL functional capabilities | |

| ADL score (0–6), mean±SD | 3.2±2.0 |

| IADL score (0–7), mean±SD | 1.3±1.6 |

| Ratio of copayments for healthcare services, n (%) | |

| 10% | 961 (69.5) |

| 20% | 137 (9.9) |

| 30% | 157 (11.4) |

| Unknown | 128 (9.3) |

| Types of dementia, n(%) | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 751 (54.3) |

| Caregivers | |

| Age, mean±SD | 52.2±13.1 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 530 (38.3) |

| Male | 853 (61.7) |

| Relationship, n (%) | |

| Mother | 575 (41.6) |

| Mother-in-law | 169 (12.2) |

| Father | 288 (20.8) |

| Father-in-law | 90 (6.5) |

| Spouse | 99 (7.2) |

| Sibling | 11 (0.8) |

| Child | 10 (0.7) |

| Friend | 5 (0.4) |

| Other (including grandparents) | 136 (9.8) |

| Contribution level for caregiving, n (%) |

|

| 1%–20% | 395 (28.6) |

| 21%–40% | 355 (25.7) |

| 41%–60% | 241 (17.4) |

| 61%–80% | 166 (12.0) |

| 81%–100% | 226 (16.3) |

| Currently employed, n (%) | 532 (38.5) |

ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

Informal care time and costs of dementia care

The mean daily informal care time was 9.36 hours in total. The time for only ADL was 4.97 hours and for only IADL was 4.39 hours. On the other hand, monthly informal care time (ADL+IADL) was 166.32 hours. Table 2 shows the differences in daily informal care time and personal cost of dementia care among the care-need levels. In this table, we did not adjust by contribution rate. Informal care times increased with care-need levels, especially in ADL. Out-of-pocket payments for LTC services were less than informal care costs in all of the care-needs levels.

Table 2.

Daily informal care time and personal costs of dementia care sorted by care-need levels

| Support-required level | Care-needs level 1 | Care-needs level 2 | Care-needs level 3 | Care-needs level 4 | Care-needs level 5 | |

| Informal care time (hours/day) | ||||||

| ADL | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.56 (3.23) | 2.23 (2.54) | 2.92 (2.90) | 3.44 (2.90) | 3.99 (2.40) | 4.60 (3.85) |

| Median ((IQR) | 1.67 (2.00) | 1.50 (2.50) | 2.00 (3.00) | 3.00 (3.50) | 4.00 (3.00) | 3.33 (4.00) |

| IADL | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.35 (2.62) | 2.46 (3.05) | 2.88 (3.26) | 2.82 (2.92) | 3.03 (2.59) | 3.45 (3.77) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.00 (2.00) | 1.50 (2.00) | 2.00 (2.00) | 2.00 (2.50) | 2.00 (3.13) | 2.00 (4.00) |

| Personal cost of dementia care (US$) | ||||||

| Informal care cost | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1518 (2017) | 1271 (1526) | 1754 (1982) | 2181 (2220) | 2112 (2104) | 2672 (2314) |

| Median (IQR) | 747 (1646) | 709 (1440) | 1090 (1697) | 1366 (2459) | 1535 (1466) | 1939 (2240) |

| OPP for LTC services covered by insurance | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 148 (190) | 158 (174) | 244 (209) | 313 (217) | 301 (202) | 318 (218) |

| Median (IQR) | 49 (172) | 49 (123) | 172 (319) | 368 (441) | 368 (196) | 368 (441) |

| OPP for care services not covered by insurance | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 158 (336) | 95 (156) | 278 (695) | 303 (543) | 241 (579) | 352 (998) |

| Median (IQR) | 49 (172) | 49 (172) | 49 (368) | 172 (319) | 49 (368) | 49 (368) |

ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; LTC, long-term care; OPP, out-of-pocket payments.

Classification with classification trees

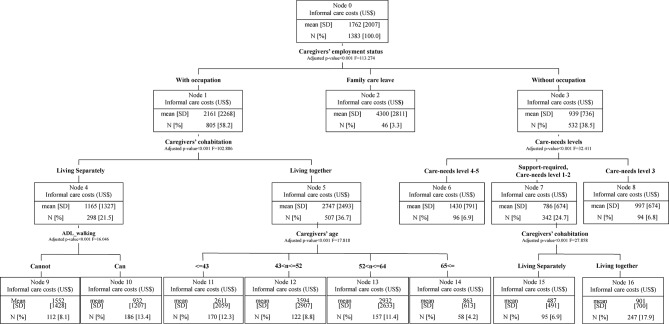

Figure 2 shows the results of CHAID analysis for informal care costs. Informal care costs were related to caregivers’ employment status, cohabitation, age and care-need levels or ADL function of people with dementia. When the caregiver acquired family care leave, informal care cost was the highest (node 2). For the caregivers who were between 43 and 52 years old (node 12) and worked outside the home as well as cohabited with people with dementia, informal care costs were high, similar to caregivers who acquired family care leave (node 2). Even if the caregiver did not work, informal care costs were higher with high care-need levels (nodes 6–8). The costs for cohabiting caregivers (node 5) were higher than for those not cohabiting (node 4). For those not cohabiting and the person with dementia who could not walk without assistance (node 9), informal care costs were higher than for those that could walk (node 10).

Figure 2.

Classification tree of χ² automatic interaction detection for informal care costs. The dendogram illustrates the combinations of independent variables to clarify who need or provide more informal care. ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; LTC, long-term care.

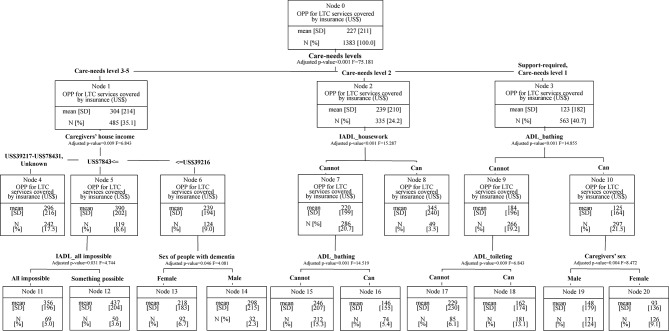

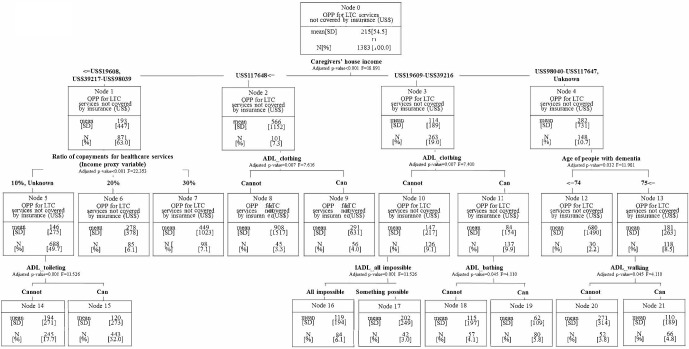

Out-of-pocket payments for LTC services covered by insurance were related to care-need levels, ADL or IADL functions, sex (both the people with dementia and caregivers) and caregivers’ household incomes (figure 3). In particular, if the people with dementia could bathe or use the toilet by themselves, out-of-pocket payments would be about 65% lower (nodes 9–10, 15–18). On the other hand, if out-of-pocket payments were not covered by insurance, they were related to caregivers’ household incomes, income proxy variable, ADL or IADL functions of people with dementia and age of people with dementia (figure 4). Both the out-of-pocket payments that were covered by insurance and those that were not were related to caregivers’ house hold income or ADL functions affected the ability to pay and service use volume.

Figure 3.

Classification tree of χ² automatic interaction detection for OPP for LTC services covered by insurance. The dendogram illustrates the combinations of independent variables to clarify who need more LTC insurance services. ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; LTC, long-term care; OPP, out-of-pocket payments.

Figure 4.

Classification tree of χ² automatic interaction detection for OPP for LTC services not covered by insurance. The dendogram illustrates the combinations of independent variables to clarify who need more LTC services without insurance. ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; LTC, long-term care; OPP, out-of-pocket payments.

Discussion

In this study, we first demonstrated that informal care time for ADL or IADL functions increased with high care-need levels as our hypothesis stipulated (Care-need level 1: 2.2 hours, level 3: 3.4 hours. level 5: 4.6 hours). Second, we established that the combination of characteristics of both people with dementia and their caregivers were related to dementia care costs through the classification tree analysis. Caregivers’ employment and cohabitation status were mainly related to informal care costs, and the costs were the highest when caregivers took nursing care leave which caregivers leave work due to caregiving (figure 2, node 2). Furthermore, when caregivers worked at an occupation and lived separately or the people with dementia could not walk, the costs doubled. Out-of-pocket payments for LTC services covered by insurance were mainly related to care-need levels and ADL and IADL functions. In the case of low care-need levels, where care was needed for toileting or bathing, high out-of-pocket payments were required for LTC insurance services. On the other hand, out-of-pocket payments were related to caregivers’ household income levels or income proxy variable. Caregivers with high annual incomes (more than US$117 648) made out-of-pocket payments for dementia care of full amounts that were two to five times more than others.

Informal care costs were mainly related to caregivers’ characteristics such as employment or cohabitation status in the classification tree, which illustrated related factors by order of precedence. In many previous studies, ADL functions or dementia severity were explained as related factors in regression models.9–12 Some studies showed caregivers’ characteristics such as employment status were related to informal care costs,9 29 30 but few studies considered all of the caregivers’ characteristics. Thus, caregiver factors may be as important as factors related to people with dementia are.

Furthermore, we considered the combination of characteristics of both people with dementia and their caregivers. For example, informal care costs doubled when caregivers lived separately and people with dementia could not walk. Many previous studies established the determinants by regression analysis.9 12 31–34 Although it is possible to understand the influence on the objective variable adjusted in the multivariate by regression analysis, the combinations between explanatory variables have not been clarified. CHAID analysis provided the classification only for related characteristics in the outcome. Such combinations suggest that support should be provided to caregivers who cannot live with people with dementia or caregivers who are not employed (figure 2, nodes 3–4).

The association between out-of-pocket payments for LTC services covered by insurance and care-need levels is reasonable because the benefit limit standard amounts for formal care services at home are decided in relation to care-need levels.35 In addition, when people with dementia had a high care-need level and their caregiver’s household income was high, out-of-pocket payments were high. Because the determination of service usage within the limit amount is a free contract, people with dementia and their caregivers may decide how they use formal care services depending on how much they can pay for services. High care-need levels,36 age10 34 36 37 and sex10 36 were related to the high costs of LTC services. Even for low care-need levels, the cost may be high when people with dementia need assistance with bathing or toileting. This was affected by LTC insurance services providing specific substitutions, such as bath assistance, and also Ku et al’s or Dodel et al’s ADL functions were related to the social care costs.9 30

Similarly, economic variables such as household income and income proxy variable were mainly related to out-of-pocket payments for LTC services not covered by insurance (figure 4). This is because people must pay the full amount if they use LTC services without insurance. In the USA, high copayments are required for the use of LTC services; however, these copayments were related to age, sex and comorbidities in the cohort study.37 A part of the result of Hurd et al was similar to our results in the case of the payments that were covered by insurance for the use of LTC services. Out-of-pocket payments not covered by insurance might occur for over the limit standard amounts or the use of LTC services not covered by insurance (eg, feeding service38). According to the questionnaire responses, people tended to pay for expendables such as diapers, employment of housekeepers and home repair such as handrail installation as out-of-pocket payments not covered by LTC insurance. Furthermore, except when caregivers’ income was high, the cost did not change significantly due to differences in ADL and IADL functions as it did for the payments that were covered by insurance. These application examples were not really affected by ADL or IADL functions.

From the viewpoint of independent variables, if people with dementia lacked some ADL function, then costs might be higher but in the case of IADL functions this was reversed. There is a possibility that some services are used to support the independent lives of people with dementia. Some people with dementia who can do housework by themselves might move or walk around more and therefore use more LTC services like commuting for care (day service) or commuting for rehabilitation. Also, care-need levels were not related to out-of-pocket payments not covered by insurance. The above application examples were also not related to care-need levels. The relationship of cohabitation or employment status was the same as in previous studies.9 29 32 While differences of burden of dementia care depended on the dementia types that existed and were pointed out,24 dementia types were not related to any other factors in this study. In our CHAID analysis, family caregivers’ economic status or severity (care-need levels) might have been more important than dementia types to dementia care costs. In creating policy for LTC services in an ageing society, we must understand the actual conditions from a societal and a personal perspective. This is true even if from a societal viewpoint, the societal cost of dementia care in the community has been established by other countries to be greater than that in institutional care.39 Furthermore, we need a wide range of perspectives of stakeholders to discuss the dementia care system, while almost all studies of economic burden of dementia stood on societal or payers’ viewpoint.7 19–21 Then, as a first step, we need to understand what people with dementia and their family caregivers are already spending too much money on. We need to recognise the complicated combination of characteristics associated with people with dementia and their caregivers. To this point, the results of this classification could be useful to understanding which situation requires more resources depending on cost types. Our results may suggest that a sustainable dementia care system in Japan should be reconstructed from a personal viewpoint.

There are some limitations to this study. First, we conducted an online questionnaire survey with caregivers of people with dementia. Traditionally, respondents who use the internet tend to be male and relatively young, reflecting the general characteristics of online research.40–42 The sample may therefore not be representative of all caregivers because the sample is limited to those who have access to the internet and are registered with an internet research company.43 Certainly, we cannot extrapolate the representative value in each node of the CHAID tree to the population as a whole. However, this study focused on finding a combination of independent variables related to the dependent variables (informal care cost and financial burden), taking into account the interaction between multiple independent variables. The significance of subgroups made by combinations of variables may not change significantly even if the population changes. Therefore, in this study, influence due to the difference between this sample and general public is not considered to be a practical problem. However, further research (eg, a paper-based questionnaire survey mailed to the family caregivers association) to collect representative samples might be needed in the future. Second, it was impossible to measure the response rate in this study. Samples were collected from an online panel until the target number set in each age category was achieved. Third, we did not consider the subjective burden of care and depressive symptoms. These mental burdens are considered to be important factors in explaining the actual state of care costs, and many previous studies in Japan have covered subjective costs.44–46 In the future, in addition to the burden of time and money, it would be preferable to measure subjective burdens. Fourth, we could not measure the clinical dementia severity data measured by such as Mini Mental State Examination or Neuropsychiatric Inventory questionnaire. However, we used care-need levels as substantial measurements of the severity data, which indicates individual requirements for amount of care determined by an evidence-based computer algorithm and expert panel. Fifth, we estimated informal care costs only by the opportunity cost approach. Some studies indicated results estimated by both opportunity cost approach and replacement cost approach. The opportunity cost approach might be underestimated in comparison to the replacement approach9 37

Conclusion

This study clarified the difference in dementia care costs between classified subgroups by considering the combination of the situations of both people with dementia and their caregivers. Informal care costs were related to caregivers’ employment and cohabitation status rather to the situation of people with dementia. On the other hand, out-of-pocket payments for LTC services were related to care-need levels and family economic status. These classifications will be useful in understanding which situation represents a greater economic burden and helpful in improving the sustainability of the dementia care system in Japan.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TN, NS and YI designed the study. All authors discussed for preparing the questionnaire. TN mainly analysed all data, and HU, SK, AW and YI advised for analysis. TN prepared the draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to rewrite it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was financially supported by a Health Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H26-ninntishou-ippan-001), the Japan Foundation for Aging and Health (H27), and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science ([A]16H02634, [A]19H01075).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: When this study was approved by the ethics committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (R0487), due to the sensitive issues, the raw data which we collected should not be treated outside of our laboratory.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Ninomiya T, Kiyohara Y, Obara T, et al. . A study on future estimation of the elderly population of dementia in Japan Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research for Ministru of Health, Labor and Welfare in 2014(H26-Tokubetsu-Shitei-036). 2014. https://mhlw-grants.niph.go.jp/niph/search/NIDD00.do?resrchNum=201405037A.

- 2. Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, et al. . World Alzheimer Report 2015: the global impact of dementia. 2015. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2015 (Accessed 3 Apr 2016).

- 3. Wimo A, Jönsson L, Fratiglioni L, et al. . The societal costs of dementia in Sweden 2012 - relevance and methodological challenges in valuing informal care. Alzheimers Res Ther 2016;8:59 10.1186/s13195-016-0215-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wimo A, von Strauss E, Nordberg G, et al. . Time spent on informal and formal care giving for persons with dementia in Sweden. Health Policy 2002;61:255–68. 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wimo A, Prince M. World alzheimer report 2010 the global economic impact of dementia. 2010. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/files/WorldAlzheimerReport2010ExecutiveSummary.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, et al. . The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimers Dement 2017;13:1–7. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jönsson L, Lin P-J, Khachaturian AS. Special topic section on health economics and public policy of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2017;13:201–4. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakabe T, Sasaki N, Uematsu H, et al. . The personal cost of dementia care in Japan: A comparative analysis of residence types. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018;33:1243–52. 10.1002/gps.4916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ku LJ, Pai MC, Shih PY. Economic Impact of Dementia by Disease Severity: Exploring the Relationship between Stage of Dementia and Cost of Care in Taiwan. PLoS One 2016;11:e0148779 10.1371/journal.pone.0148779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leicht H, Heinrich S, Heider D, et al. . Net costs of dementia by disease stage. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;124:384–95. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leicht H, König HH, Stuhldreher N, et al. . Predictors of costs in dementia in a longitudinal perspective. PLoS One 2013;8:e70018 10.1371/journal.pone.0070018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farré M, Haro JM, Kostov B, et al. . Direct and indirect costs and resource use in dementia care: A cross-sectional study in patients living at home. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;55:39–49. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities in 2016. 2017. http://www.stat.go.jp/data/shakai/2016/pdf/gaiyou2.pdf (Accessed 6 Mar 2018).

- 14. Wimo A, Jonsson L, Zbrozek A. The Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD) instrument is valid for assessing informal care time in community-living patients with dementia. J Nutr Health Aging 2010;14:685–90. 10.1007/s12603-010-0316-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wimo A, Gustavsson A, Jönsson L, et al. . Application of Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD) instrument in a global setting. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2013;9:429–35. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mesterton J, Wimo A, By A, et al. . Cross sectional observational study on the societal costs of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2010;7:358–67. 10.2174/156720510791162430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Mechanism and procedures for cartification of care-needs levels. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-11901000-Koyoukintoujidoukateikyoku-Soumuka/0000126240.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2019).

- 18. Lin HR, Otsubo T, Imanaka Y. Survival analysis of increases in care needs associated with dementia and living alone among older long-term care service users in Japan. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:182 10.1186/s12877-017-0555-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mauskopf J, Mucha L. A Review of the Methods Used to Estimate the Cost of Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementiasr 2011;26:298–309. 10.1177/1533317511407481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quentin W, Riedel-Heller SG, Luppa M, et al. . Cost-of-illness studies of dementia: a systematic review focusing on stage dependency of costs. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;121:243–59. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01461.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schaller S, Mauskopf J, Kriza C, et al. . The main cost drivers in dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;30:111–29. 10.1002/gps.4198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. An estimate of the total worldwide societal costs of dementia in 2005. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3:81–91. 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johannesson M, Borgquist L, Jönsson B, et al. . The costs of treating hypertension--an analysis of different cut-off points. Health Policy 1991;18:141–50. 10.1016/0168-8510(91)90095-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Costa N, Ferlicoq L, Derumeaux-Burel H, et al. . Comparison of informal care time and costs in different age-related dementias: a review. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:1–15. 10.1155/2013/852368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Åkerborg Ö, Lang A, Wimo A, et al. . Cost of Dementia and Its Correlation With Dependence. J Aging Health 2016;28 10.1177/0898264315624899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bergvall N, Brinck P, Eek D, et al. . Relative importance of patient disease indicators on informal care and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2011;23:73–85. 10.1017/S1041610210000785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rattinger GB, Schwartz S, Mullins CD, et al. . Dementia severity and the longitudinal costs of informal care in the Cache County population. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2015;11:946–54. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gustavsson A, Brinck P, Bergvall N, et al. . Predictors of costs of care in Alzheimer’s disease: a multinational sample of 1222 patients. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:318–27. 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gervès C, Chauvin P, Bellanger MM. Evaluation of full costs of care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease in France: The predominant role of informal care. Health Policy 2014;116:114–22. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dodel R, Belger M, Reed C, et al. . Determinants of societal costs in Alzheimer’s disease: GERAS study baseline results. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:933–45. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, et al. . Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2013;368:1326–34. 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dodel R, Belger M, Reed C, et al. . Determinants of societal costs in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2015;11:933–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J. Economic valuation and determinants of informal care to people with Alzheimer’s disease. The European Journal of Health Economics 2015;16:507–15. 10.1007/s10198-014-0604-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hajek A, Brettschneider C, Ernst A, et al. . Longitudinal predictors of informal and formal caregiving time in community-dwelling dementia patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2016;51:607–16. 10.1007/s00127-015-1138-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tokyo Metropolitan Government. The Long-term Care Insurance System:Long-term Care Service Costs to Be Paid by th User. http://www.fukushihoken.metro.tokyo.jp/kourei/koho/kaigo_pamph.files/p.10kaigohoken-english.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2019).

- 36. Lin H-R. Tetsuya Otsubo and YI. The Effects of Dementia and Long-Term Care Services on the Deterioration of Care-needs Levels of the Elderly in Japan. Medicine 2015;94:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, et al. . Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1326–34. 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Reference case examples of long-term care insurance services for constructing community-based integrated care system. 2016. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12300000-Roukenkyoku/guidebook-bunkatu1.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2019).

- 39. König HH, Leicht H, Brettschneider C, et al. . The costs of dementia from the societal perspective: is care provided in the community really cheaper than nursing home care? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:117–26. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eysenbach G, Wyatt J. Using the Internet for surveys and health research. J Med Internet Res 2002;4:e13 10.2196/jmir.4.2.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fujihara S, Inoue A, Kubota K, et al. . Caregiver burden and work productivity among japanese working family caregivers of people with dementia. Int J Behav Med 2018;11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Gelder MM, Bretveld RW, Roeleveld N. Web-based questionnaires: the future in epidemiology? Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:1292–8. 10.1093/aje/kwq291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Washio S, Toyoshima Y, Yamazaki R, et al. . Factors related to the care burden of family caregivers - focusing on the care burden of caregivers of elderly who needs nursing care -]. Japanese J Clin Exp Med = Rinshou to Kenkyuu 2012;89:1687–91. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Arai Y, Kumamoto K, Mizuno Y, et al. . Depression among family caregivers of community-dwelling older people who used services under the Long Term Care Insurance program: a large-scale population-based study in Japan. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:81–91. 10.1080/13607863.2013.787045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Washio S, Nogami Y, Motoyama S, et al. . Long-Term Care Insurance Act amendment and care burden of family caregivers for elderly who need long-term care at home]. Japanese J Clin Exp Med = Rinshou to Kenkyuu 2015;92:75–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.