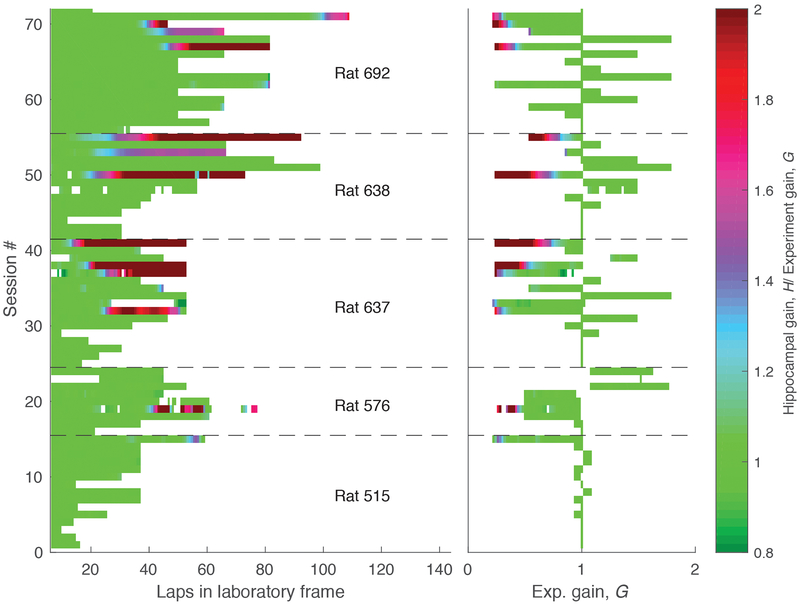

Extended Data Figure 4: Summary of dataset.

Each row indicates one of the 72 sessions composing the dataset during the period when the landmarks were on. In the left plot, the x-axis is laps in the lab frame. In the right plot the x-axis is experimental gain, G. The sessions are chronologically ordered (bottom to top). Sessions from different animals are separated by dashed lines. In all rats, we typically performed smaller manipulations in G first, since initial landmark failure tended to occur at larger manipulations of G. Once landmark control failed, it tended to fail more frequently. The color represents the ratio between hippocampal and experimental gains (H/G, color bar, right). Green (H/G = 1) indicates landmark control. Four of the rats (576, 637, 638, 692) experienced landmark failure (red portions of trials). Failures only happened when the G was less than one (i.e., the landmarks moved in the same direction as the rat) and generally occurred at low values of G (less than 0.5) and after rats had experienced multiple gain manipulation sessions over days. The asymmetry in landmark control between G < 1 and G > 1 is similar to a study of medial entorhinal cortex by Campbell and colleagues41. In this study, mice ran on a VR linear track controlled by a stationary treadmill, and the authors manipulated the gain factor between distance traveled on the treadmill versus the VR track. Grid cells showed asymmetric responses to increases versus decreases of the gain. Gain increases (i.e., G > 1) caused phase shifts in the spatial firing patterns but gain decreases (i.e., G < 1) caused changes in the spatial scales. These results were elegantly explained by a model of how grid cells respond to conflicts between self-motion and landmark cues. Although this paper did not address the issues of path integration gain recalibration as in the current study, its results may provide a causal explanation for the asymmetric responses of place cells to the landmark manipulations seen in the present study.