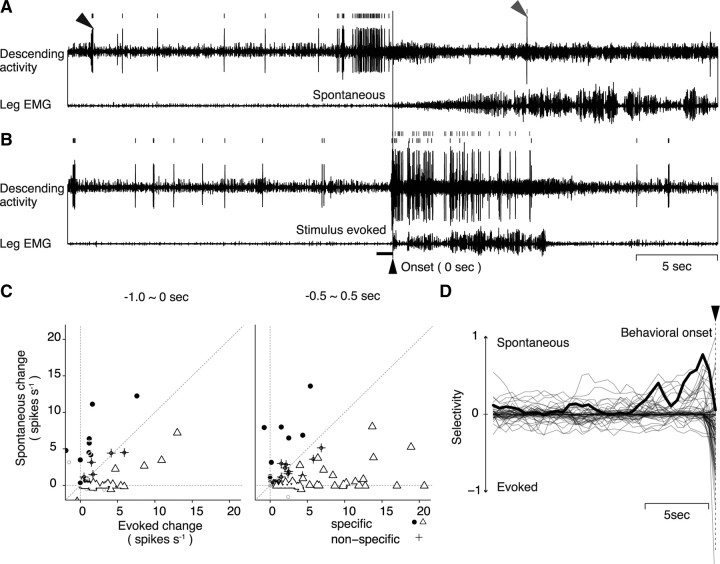

Figure 4.

Selective activity of descending units for spontaneous and mechanical stimulus-evoked walking. A, Descending unit activities recruited for the spontaneous initiation of walking. B, Unit activities associated with mechanical stimulus-evoked initiation of walking recorded from the same animal as in A. The horizontal bar on the left side of the behavioral onset indicates the approximate period of mechanical stimulation. Two different units were selectively recruited for the spontaneous (black arrowhead and spike trains) and stimulus-evoked (gray arrowhead and spike trains) walking. C, Activity changes in the descending units associated with spontaneous or mechanical stimulus-evoked initiation of walking. Each symbol represents the averaged difference in the spike discharge number of each unit between the control and the test period before the spontaneous and stimulus-evoked walking, plotted against the ordinate for the former and the abscissa for the latter type of walking. The control period was 1 s in duration, starting at 20 s before the behavioral onset, and common to the left and right panel of C. The test period was 1 s in duration and started 1 s (left) or 0.5 s (right) before the behavioral onset. If the difference in the spontaneous or mechanical stimulus-evoked walking was judged to be statistically meaningful by model selection, the unit was classified into spontaneous (filled circle) or evoked walking-specific unit (open triangle), respectively. The unit that showed a meaningful difference in both types of walking behavior was plotted on or near the diagonal and classified into the nonspecific unit (cross). The test period for the right panel could detect larger number of evoked walking-specific units that increased spike activity just before or almost at the same time as the behavioral onset. D, Temporal changes in the selective activity of descending units before the behavioral onset of spontaneous and mechanical stimulus-evoked walking. The test period was shifted from 19 to 0.5 s before the behavioral onset (from −19 to −0.5 s) with the time step of 0.5 s. Each of the superimposed 81 traces shows the temporal change of behavioral selectivity of each unit obtained from 12 animals. We measured the distance from the diagonal to quantify the behavioral selectivity of unit discharges for the test period at each time. The ordinate is the measure of distance of each unit from the diagonal, normalized to the maximal value in the spontaneous domain to indicate the behavioral selectivity of the unit. The zero level means that the unit showed no selective activity for either spontaneous or evoked behavior. The trace deflects upward from zero when the unit increases its spike discharge at a certain time before the onset of spontaneous walking, whereas it deflects downward when the unit increases its spike activity at that time before the onset of mechanical stimulus-evoked walking. The abscissa indicates time. The measurement in each of the successive test period with time step of 0.5 s was connected with its neighbors by a straight line to make up the behavioral selectivity profile of the unit over the prebehavioral time period. The unit illustrated in A is indicated by a thick line.