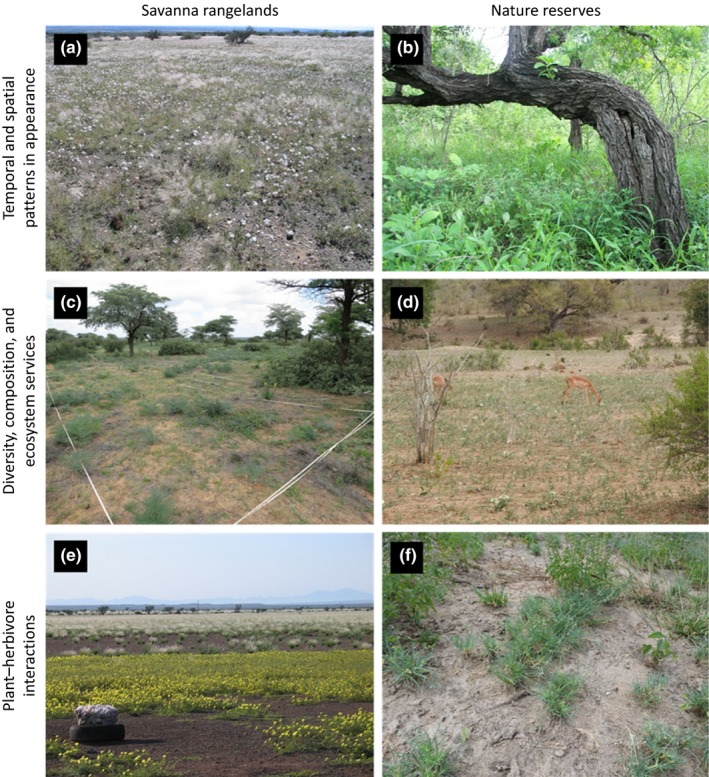

Figure 1.

Examples taken from rangeland systems and protected areas illustrating multifaceted aspects of forb ecology in savannas (which may apply to both systems interchangeably). (a) Flower display of Monsonia umbellata in a year providing opportunity to locally codominate the herbaceous layer together with the grass Stipagrostis uniplumis under low grazing pressure (arid Nama Karoo savanna, Namibia; nd); (b) fertility island effect of a savanna tree contributing to a structurally diverse savanna landscape with distinct herbaceous communities including a variety of specialized forb species (semiarid Lowveld savanna, Kruger National Park, South Africa; fs); (c) A high diversity of partly poisonous and unpalatable forbs (including geophytes) determining herbaceous biomass production and forage availability in an overgrazed savanna system (semiarid Kalahari savanna, South Africa; nd); (d) postdrought flush of forbs (including geophytes) providing nutritious forage to a variety of insects and megafauna (semiarid Lowveld savanna, Kruger National Park, South Africa; fs); (e) carpet of prostrate Tribulus spp. at a lick. These species are adapted to, profit from and indicate increased livestock activity (arid Nama Karoo savanna, Namibia; nd); (f) mesoherbivores, particularly impala are responsible for creating and maintaining forb forage patches with feedbacks on local plant species pools, resource use, and foraging behavior of herbivore communities and consequently biodiversity (semiarid Lowveld savanna, Kruger National Park, South Africa; fs). Pictures: fs = F. Siebert, nd = N. Dreber