Abstract

The spectral (frequency) and amplitude cues in speech change rapidly over time. Study of the neural encoding of these dynamic features may help to improve diagnosis and treatment of speech-perception difficulties. This study uses tone glides as a simple approximation of dynamic speech sounds to better our understanding of the underlying neural representation of speech. The frequency following response (FFR) was recorded from 10 young normal-hearing adults using six signals varying in glide direction (rising and falling) and extent of frequency change (, , and 1 octave). In addition, the FFR was simultaneously recorded using two different electrode montages (vertical and horizontal). These factors were analyzed across three time windows using a measure of response strength (signal-to-noise ratio) and a measure of temporal coherence (stimulus-to-response correlation coefficient). Results demonstrated effects of extent, montage, and a montage-by-window interaction. SNR and stimulus-to-response correlation measures differed in their sensitivity to these factors. These results suggest that the FFR reflects dynamic acoustic characteristics of simple tonal stimuli very well. Additional research is needed to determine how neural encoding may differ for more natural dynamic speech signals and populations with impaired auditory processing.

1. Introduction

Everyday listening environments are filled with dynamic auditory signals like speech that vary in frequency and amplitude. Speech sounds can be conceptualized as multi-layered collections of acoustic features such as onsets, offsets, fundamental frequency, harmonics, formants, formant transitions, fine structure, and the speech envelope (Abrams & Kraus, 2009). Because speech understanding depends upon how well the auditory system encodes dynamic acoustic cues, a better understanding of the underlying neural processing of dynamic stimuli may help improve diagnosis and treatment of listening difficulties experienced in complex listening environments (e.g., when background noise is present). Speech is an extremely complex signal, and often much simpler stimuli are used in psychophysical and neurophysiological experiments to allow for more tightly controlled study of how basic speech-related acoustic cues may be processed. For example, simple tone glides are employed as a starting point to study the neural coding of frequency change in speech because they can be designed to approximate the trajectories of dynamic cues such as formant transitions and voice-pitch contours (e.g., Clinard & Cotter, 2015).

The frequency following response (FFR) is a useful tool for examining brainstem-level neural coding of the different types of frequency changes in auditory stimuli (Aiken & Picton, 2008). The FFR represents neural processing from the cochlea to the inferior colliculus (Chandrasekaran & Kraus, 2010), with potential contributions from the auditory cortex as well (Coffey et al., 2016). The sensitivity of the FFR to dynamic characteristics of both simple and complex signals give it broad utility for studying the encoding of acoustic characteristics important for speech discrimination (Batra, Kuwada, & Maher, 1986; Krishnan, 2007; Skoe & Kraus, 2010). Our focus here is to improve our understanding of the neural response to simple tone glides that differ with respect to frequency extent and glide direction in preparation for using more complex and realistic approximations of speech in upcoming investigations.

Both psychophysical (Collins and Cullen, 1978; Gordon and Poeppel, 2001) and physiological (Maiste and Picton, 1989; Krishnan and Parkinson, 2000) studies have demonstrated improved responses to rising stimuli. It has been suggested the source of this asymmetry is cochlear in origin, due to traveling-wave dispersion along the basilar membrane (Collins and Cullen 1978; Krishnan and Parkinson, 2000; Gordon and Poeppel, 2001). The findings of Gordon and Poeppel (2001) suggest that the degree of asymmetry in identifications of tone glide direction is related to the rate of frequency change: listeners were better at identifying rising tones than falling tones at rates between 6.2 and 25.0 octaves/second. However, the dispersion rate in the cochlea is likely too rapid to account for directional asymmetries in glide perception, and asymmetries have not always been observed (Arlinger et al., 1977; Elliot et al., 1989; vanWieringen and Pols, 1994; Clinard and Cotter, 2015). Nevertheless, the effects of glide rate can still be observed in the neural response: Clinard and Cotter (2015) found weaker stimulus-to-response correlations for tonal glides with a faster rate of frequency change (6667 Hz/s) compared to glides with shallower slopes (1333 Hz/s). Apart from the direction and rate of frequency change, it appears that absolute stimulus frequency is itself a key factor, given that the FFR generally represents lower frequencies better than higher frequencies (Krishnan & Parkinson, 2000; Galbraith et al., 2000).

When assessing neural encoding of tone glides, FFR electrode montage has a significant impact on the recorded responses. Galbraith et al. (2000) found that, compared to a vertical montage (vertex to linked mastoids), recording from a horizontal electrode montage (ear-to-ear) generally resulted in larger amplitudes and higher signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) for frequencies between 133 and 950 Hz. Especially pronounced differences were observed above 500 Hz, suggesting that the horizontal montage targets an acoustic-nerve generator—known to phase-lock to frequencies as high as 4–5 kHz (Rupert, Moushegian, et al., 1963; Tasaki, 1954)—whereas the vertical montage likely reflects more central brainstem generators (Marsh, Brown, et al., 1975; Galbraith, 1994). In addition, King et al. (2016) reported that FFRs had shorter latencies when recorded with a horizontal montage as opposed to a vertical montage, providing further support for the hypothesis that horizontal montage reflects activity that is more peripheral than the activity captured by the vertical montage.

The current study was designed to target the three key factors described above—glide direction, rate of frequency change, and recording electrode montage—in a unified experimental paradigm aimed at investigating how these factors interact. This is a necessary preparatory step for the systematic investigation of more complex and speech-like dynamic stimuli in the future. Our review of the literature leads us to hypothesize that slowly rising tone glides will result in the most robust FFRs, and that constraining the average frequency extent of all glides to a range centered logarithmically at 500 Hz will reveal consistent effects of electrode montage.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Ten adults (7 female, 3 male) aged 24–33 years (mean = 28.1, SD = 3.6) participated in this study. All participants had normal hearing in the test ear, defined as thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL at all octave frequencies from 250 to 4000 Hz. None reported taking sleep-inducing or mood-altering medications. All were paid for their participation and provided informed consent.

2.2. Stimuli

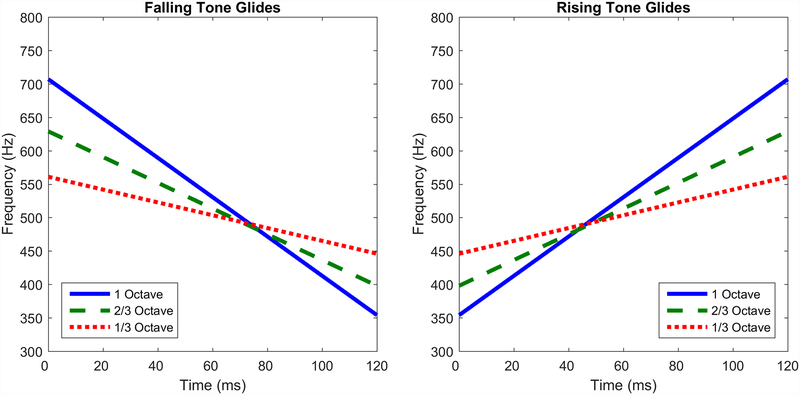

Stimuli were six tone glides that varied in direction (rising or falling in frequency) and extent of total change in frequency (, , or 1 octave). Starting and ending frequencies are given in Table 1. The frequency extrema for each glide were centered around 500 Hz on a log2 (octave) scale, and instantaneous frequency changed linearly over the glide’s duration of 120 ms, as shown in Figure 1. Glides were generated in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) as zero-phase sine waves with 5-ms cosine on-ramps and off-ramps. To allow for alternating-polarity presentations, a phase-inverted copy of each glide was derived by multiplying the amplitude at each sample point by −1. Stimuli were digitally stored as 44.1-kHz WAV files with 16-bit LPCM encoding.

Table 1.

Extent of frequency change, rate of change, and starting/ending frequencies of test stimuli.

| Rising (Hz) | Falling (Hz) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extent | Rate (Hz/s) | Starting Frequency | Ending Frequency | Starting Frequency | Ending Frequency |

| octave | 958 | 446 | 561 | 561 | 446 |

| octave | 1925 | 398 | 629 | 629 | 398 |

| 1 octave | 2942 | 354 | 707 | 707 | 354 |

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the six tone-glide conditions. The red, blue, and green lines represent the 1-octave, -octave, and -octave extents, respectively. The left panel shows falling glides and the right panel shows rising glides. The stimuli were designed so that for each extent, the extreme frequencies are the same for both rising and falling glides.

2.3. Data Acquisition and Processing

Testing took place inside a sound-treated and electrically shielded test booth where participants lay comfortably reclined in an armchair with footrest extended. To minimize myogenic artifacts, participants were encouraged to relax and were instructed to refrain from unnecessary movement; sleeping was encouraged. The presentation order of the six glides was randomized across participants. Each condition lasted about 10 min, and breaks between stimulus conditions were 2-min periods of silence. Participants were allowed to take longer stretching/walking breaks as needed. Study visits lasted no more than four hours, including consenting, audiometric testing, and setup.

Stimuli were presented monaurally at 80 dB SPL using Stim2 software and digital-to-analog conversion hardware (Compumedics Neuroscan, Charlotte, NC) and an ER-3A insert earphone (Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL). The transducer was treated with mu-metal magnetic shielding, and its output was routed to the participant’s left ear using 51 cm of silicone sound tubing (double the regular ER-3A length) and a 2.5-cm foam insert tip. The distance between the transducer and the participant’s ear was always at least 36 cm. FFRs were recorded to both inverted and non-inverted stimuli in alternating polarity for a total of 3000 sweeps per stimulus condition (1500 per polarity). Inter-stimulus intervals (offset to onset) were randomly jittered among 146, 163, and 180 ms to prevent neural entrainment, which can occur in response to a rhythmic presentation (Gao et al., 2009).

FFRs were recorded at a sampling rate of 20 kHz with an online analog filter passband of 100–3000 Hz using SynAmps RT amplifiers and Scan Acquire 4.5 software (Compumedics Neuroscan, Charlotte, NC). Recordings were made using pre-gelled, self-adhesive, snap-on Ag/AgCl electrodes (Neuroline 720, Ambu USA, Columbia, MD) in a six-channel montage. The non-inverting (active) electrodes were placed at Cz (vertex), C7 (the 7th cervical vertebra), M1 (left mastoid), and Fz (halfway between Cz and the nasion); the inverting (reference) electrode was positioned at M2 (right mastoid); and the common ground electrode was located at Fpz. Two single-channel montages were used for analysis: one vertical (Cz to C7) and one horizontal (A1 to A2). To obtain the vertical montage, the data were digitally re-referenced in the Neuroscan Edit 4.5 software such that C7 became the inverting electrode; the Cz channel was then extracted for analysis. The horizontal montage consisted of the A1 channel from the original A2-referenced recording.

To verify that the mu-metal shielding was functioning as intended and that responses were not contaminated by electromagnetic radiation from the transducer, each recording session ended with an artifact-control testing block, in which a -octave rising tone was played through the ER-3A; the transducer was positioned the same as in previous blocks, but this time without any coupling to the ear. To further ensure the stimulus was inaudible, the participant’s ears were occluded with Sound Guard Two-Color disposable ear plugs made from polyvinyl chloride foam. Visual inspection of these artifact runs confirmed that responses were not contaminated by stimulus artifacts.

The continuous electroencephalogram was divided into epochs extending from −40 ms to 240 ms re: stimulus onset. Each recorded epoch was baseline-corrected by vertically aligning the sweep such that the mean amplitude in the pre-stimulus interval (−40 to 0 ms) was equal to zero. Epochs that contained activity exceeding ±30 μV were rejected. If responses from one polarity had more accepted sweeps than from the other polarity, sweeps were discarded starting with the last-collected sweep until the number accepted sweep was equal between polarities. Accepted sweeps were averaged separately for each polarity. Then, a differential average was calculated by subtracting the non-inverted average from the inverted average and dividing the result by two. This operation accentuates the activity phase-locked to the stimulus fine-structure (i.e., the FFR). To isolate the frequency range of interest, average responses were passed through a 401-tap digital FIR filter with passband of 300–800 Hz, created using Matlab’s fdesign.bandpass and design functions. As designed, the filter had a length of 20 ms and an order of 400, but because the filter was applied using Matlab’s filtfilt function, which processes in both forward and reverse directions to eliminate phase delays, the effective filter order was 800. The transition bandwidth on each side was about 100 Hz, and attenuation in the stopband was always at least 52 dB relative to the passband. Passband ripple was virtually nonexistent (−0.02 dB).

Prior to evaluating the FFRs, we attempted to time-align the averaged responses so that each portion of the response could be matched up with the portion of the stimulus that evoked it. To accomplish this, we calculated the cross-correlation function between the stimulus and the response (see Rabiner & Schafer, 2007, for a tutorial) and estimated the time-delay between stimulus and response by assuming it to be equal to the lag at which the cross-correlation function was at its maximum. The lag was allowed to range between 2 and 22 ms, which encompasses all physiologically feasible values for brainstem generator sites (King et al., 2016). The calculation and alignment procedure was performed separately for each subject and each condition. To allow one-to-one mapping between the two series, the stimulus was first downsampled from from 44.1 kHz to 20 kHz to match the sampling rate of the response, using the resample function in Matlab’s Signal Processing Toolbox. We also removed the pre-stimulus portion of the response and zero-padded the end of the stimulus as needed to ensure the two signals always had an equal number of samples. The stimulus-to-response lags were subtracted from the original timestamps on the FFRs to bring them into alignment with their evoking stimuli; afterward, the portion of each response that trailed beyond the stimulus duration was trimmed away. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the lag values obtained from the cross-correlation analysis.

Table 2.

Lag Statistics by Montage

| Lag (ms) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montage | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. |

| Horizontal | 7.27 | 7.80 | 1.55 | 4.10 | 10.45 |

| Vertical | 9.75 | 9.55 | 2.94 | 4.65 | 19.75 |

2.4. Response Characterization

To capture the dynamic nature of the stimulus, the trimmed, time-aligned response waveform was divided into three adjacent, non-overlapping 40-ms time windows: 0–40 ms, 40–80 ms, and 80–120 ms, relative to the estimated onset of the electrophysiological response to the stimulus. In each window, we quantified the FFR in two ways: (1) response strength was measured using the signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) of the response, and (2) temporal coherence between the stimulus and response was measured using the stimulus-to-response correlation coefficient (SRCC). The purpose of using these measures was to emphasize different aspects of the response relevant to encoding frequency changes within a signal.

In order to pinpoint a stimulus frequency for SNR analysis, which is not a straightforward task for signals with continuously varying frequency such as glides, symmetrical 40-ms Blackman windows were applied to each of the three stimulus and response segments. We required a “peaky” time-domain window to produce clear spectral maxima in the context of a moving signal. Of the commonly-used windowing functions, the Blackman window was chosen specifically because of its efficacy in minimizing spectral splatter. The magnitude of the FFR in each time window was estimated by first determining the stimulus frequency of each window (defined as the frequency of the largest discrete Fourier transform component in the stimulus), then calculating the peak magnitude of the discrete Fourier transform of the response within a ±25 Hz range around that stimulus frequency. The noise floor associated with each response was estimated from the average pre-stimulus baseline (−40 ms to 0 ms relative to stimulus onset) as the mean discrete Fourier transform magnitude in a ±25 Hz range around the stimulus frequency (i.e., the same frequency range analyzed to locate the signal). The SNR, in decibels, was calculated as 20 times the base-10 logarithm of the ratio of the signal and noise voltages estimated above:

The second measure, the SRCC, was obtained by scaling the response to have equal rms voltage to the stimulus, taking the dot-product of the stimulus and the response, then normalizing the result on a 0–1 scale by dividing by sum of squares of the stimulus. Or, equivalently:

3. Results

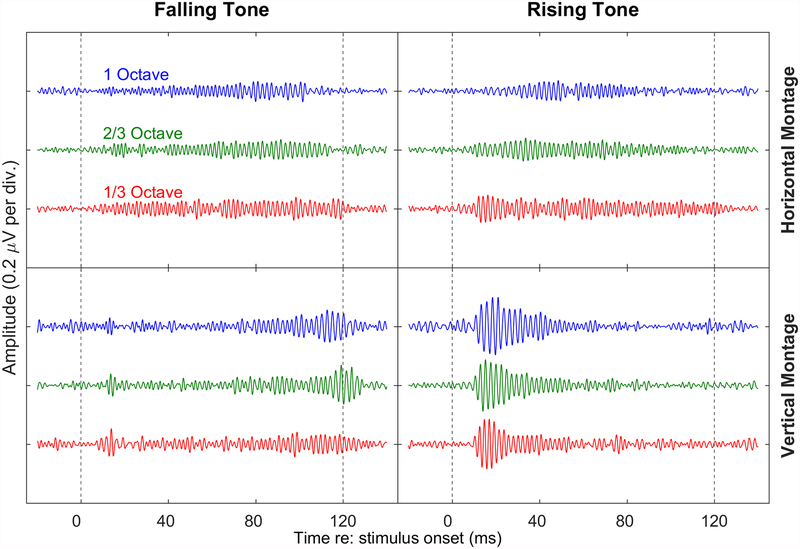

Grand-average time waveforms in response to each of the six stimulus condition types in each of the two analysis montages are shown in Figure 2. A four-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) was completed with the factors of Window (first, second, and third), Direction (rising and falling), Extent (, , and 1 octave), and Montage (vertical and horizontal) as independent variables and SNR and SRCC as dependent variables. Greenhouse-Geisser corrections (Greenhouse and Geisser, 1959) were applied to the degrees of freedom in cases where the assumption of sphericity was rejected by Mauchly’s test (Mauchly, 1940). Significant main effects and interactions are reported below under the subheadings for each of the independent variables. The details of the statistical analysis are presented in Appendix A. Also available are the deidentified data used in obtaining these results, along with all code and output from the analyses.

Figure 2.

Grand-average time waveforms (n=10) for the six tone-glide conditions tested for each of the two electrode montages analyzed. Within each quadrant, glide extent is indicated from top to bottom by blue (1 octave), green ( octave), and red ( octave) lines for each of the direction-montage combinations. The variation in response amplitude over the epoch duration is greater for the vertical montage than for the horizontal, with larger average onset amplitudes for the rising tones than for the falling tones.

3.1. Time Window

There was a significant main effect of Window on response SNR (F(1.14, 10.28) = 4.91, p = .047). An average SNR increase of about 1 dB across conditions was observed in the first window relative to the second and third windows, corresponding to response onset (Figure 2). In contrast, the main effect of window on the SRCC was not significant (F(2, 18) = 1.234, p = .315), indicating that although the response strength was larger early in the response, temporal coherence between the stimulus and response appeared to be consistent across the analysis windows. A significant Montage × Window interaction was observed for both the SNR (F(2, 18) = 5.56, p = .013) and the SRCC (F(2, 18) = 4.08, p = .035), reflecting that the main effect of Window was driven primarily by responses in the vertical montage, whereas the horizontal-montage FFRs showed little to no early boost in the response SNR. A significant Extent × Montage × Window interaction on SRCC was also observed (F(4, 36) = 2.76, p = .042).

3.2. Direction

There was no significant main effect of Direction (rising or falling) on either the SNR (F(1, 9) = 0.691, p = .427) or the SRCC (F(1, 9) = 0.183, p = .679); the difference in marginal means between the rising glides and the falling glides was less than 0.4 dB for the SNR and less than .01 for the SRCC. However, Direction was involved in two significant interactions on the SRCC: Direction × Window (F(1.29, 12.20) = 28.13, p < .001) and Direction × Montage × Window (F(2, 18) = 5.89, p = .011). The bottom two panels of Figure 3 show that the average responses were more temporally correlated to rising stimuli in the first window and falling stimuli in the third window, with differences more pronounced for the vertical montage than for the horizontal montage.

Figure 3.

Effect of Direction, Montage, and Window on SNR and SRCC. Solid and dashed lines indicate the horizontal and vertical montages respectively. Top panels depict the SNR across the three windows for the falling (left panels) and rising (right panels) tone glides; bottom panels depict the same for the SRCC. On average, the responses from the horizontal montage exhibit larger SNRs and stronger correlations than the vertical montage. A Window effect is also seen for the vertical montage.

3.3. Extent (Slope)

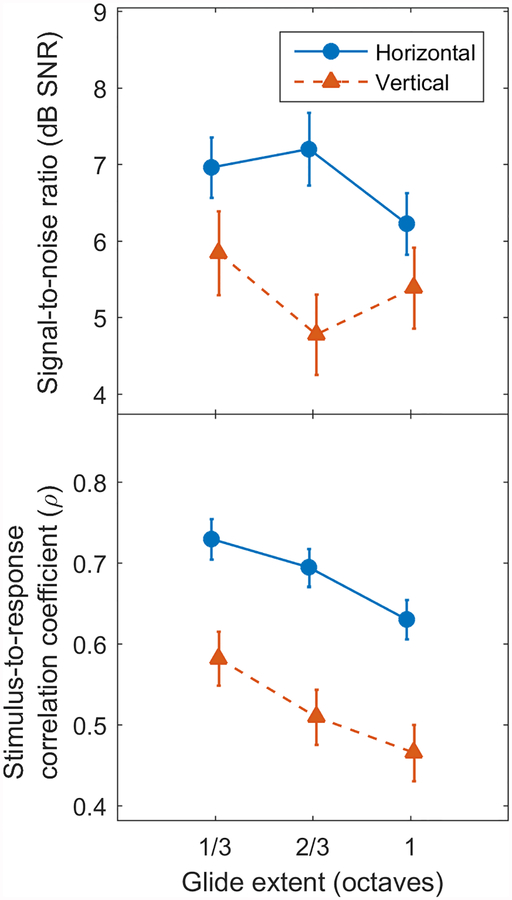

The RM-ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of Extent on both SNR (F(2, 18) = 4.81, p = .021) and SRCC (F(2, 18) = 13.12, p < .001). On average, smaller extents (shallower slopes) produced stronger responses, in terms of both SNR and SRCC, which is demonstrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Effect of Montage on the SNR (top) and SRCC (bottom) for the different tone-glide extents. Averaged across the three time windows, responses obtained from the horizonal montage (blue solid line) generally had both larger SNRs and SRCCs than those from vertical montage (red dotted line). In addition, smaller extents (shallower slope) resulted in improved responses to tone glides with smaller extents (shallower slope), especially for the temporal coherence measure.

3.4. Electrode Montage

In addition to the interactions involving Montage described above, there was also a significant main effect of Montage on both SNR (F(1, 9) = 5.82, p = .039) and SRCC (F(1, 9) = 12.01, p = .007). As seen in Figure 4, the nature of the effect was the same for both measures: the horizontal montage resulted in higher SNRs and SRCCs on average. However, the significant Montage × Window and Extent × Montage × Window interactions indicate that this effect was not uniform across all conditions. In the first window of the rising tones, for instance, the effect was negated (SRCC) or reversed (SNR) as seen in Figure 3.

4. Discussion

The dynamic frequency and amplitude cues present in the speech signal must be encoded by the auditory system. The current study employed the FFR to investigate the auditory neural coding of simple tone glides that varied in Direction and Extent (see Table 1). To explore the properties of the phase-locked brainstem response to stimuli that change in frequency over time, FFRs were characterized across three consecutive time windows and with two different electrode montages (vertical and horizontal). In quantifying the response, we used two different measures (SNR and SRCC) to emphasize two distinct aspects of the FFR (response strength and temporal coherence, respectively).

4.1. Differential Coding of Direction and Extent

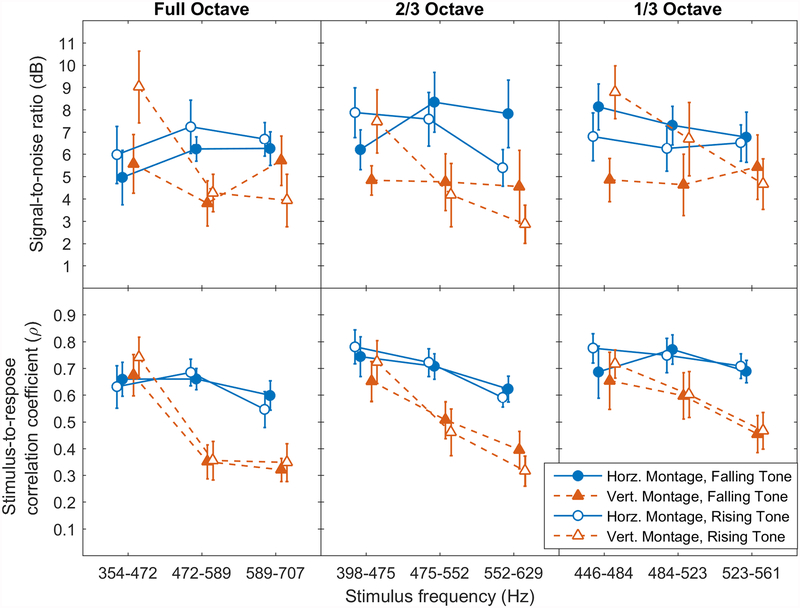

The FFR is driven primarily by the acoustic properties of the stimulus, up to the frequency limit of phase-locking; therefore, we anticipated that tone-glide Extent and Direction would impact measures of FFR response strength and temporal coherence. In agreement with previous findings (Clinard & Cotter, 2015), smaller extents (shallower slopes) produced more robust responses, as measured by both SNR and SRCC. Because stimulus duration was equal across conditions, changes in the frequency extent of the glides were directly proportional to changes in their linear slopes. We believe that the effect is likely related to the glide slopes rather than their extent per se, because it may be more difficult for the firing of auditory neurons to phase-lock to a tone with rapidly changing frequency. That the same pattern is still present after controlling for possible effects of frequency and window further supports this interpretation. When glides are passing through the same frequency region at different rates—as in the second time window of each condition in this study—the glides passing through more quickly elicit weaker temporal coherence to the stimulus than do those moving more slowly (Figure 5, bottom row). Similar general effects of slope are apparent in Krishnan et al. (2009) where steeper stimulus slopes tend to result in reduced response pitch strengths for the English-speaking participants.

Figure 5.

SNR and SRCC measures by signal frequency. Effects of Direction (rising—open symbols; falling—solid symbols) and Montage (horizontal—triangles; vertical—circles) are shown for each Extent (columns). The responses obtained in the vertical montage (bottom row, dotted lines) show clear evidence of a relationship between stimulus frequency and the temporal coherence measure, with lower frequencies producing stronger correlations regardless of Direction.

In the case of SNR, there is a confounding factor that could also be contributing to this pattern: namely, that steeper glides inherently have reduced spectral density due to faster changes in instantaneous frequency. When we applied the same analysis methods to the stimuli we found reductions in spectral peak amplitudes of 3.6% for the -octave stimuli and 8.4% for the 1-octave stimuli (both relative to the -octave stimuli, which had the largest spectral peaks). However, this cannot account for the same pattern being present in the SRCC data, where no spectral analysis is performed and overall response amplitude is inconsequential. This was empirically verified by creating versions of the stimuli that were corrupted with zero-mean Gaussian noise and correlating them with their uncorrupted counterparts. Comparing these correlations across slopes showed that correlation strength did not pattern with slope in any consistent way.

Figure 5 also illustrates that glide direction is less important than average frequency, especially for the SRCC measure. These results contrast with previous findings of Krishnan and Parkinson (2000), who found larger amplitudes for rising tones than for falling tones. However, they used shorter duration stimuli (80 ms) and did not assess temporal coherence. It may be that because the signal used by Krishnan et al is shorter, the neural response to the onset may have greater influence than for the longer signal that we have used.

4.2. Frequency and Onset Effects

A main effect of Window was found for the response amplitude measure (SNR) but not for the temporal alignment measure (SRCC), probably because the FFR, like most evoked responses, has a larger amplitude near the onset of the stimulus. This is apparent in Figure 2, where a larger response amplitude is seen shortly following the onset of each stimulus, especially for the vertical montage. As a result, the response amplitude in the first window was found to be larger than would be expected based on Direction or frequency content alone. It is important to note, however, that larger response SNRs near stimulus onset did not affect temporal coherence as measured by the SRCC. Therefore, we conclude that the onset effect fundamentally represents an increase in absolute response magnitude, which would have a large effect on SNRs and very little effect on SRCCs.

The possible role of frequency in modulating the onset effect is important to consider given the trends observed in these data. Vertical-montage results from Figure 5 illustrate larger absolute SNR differences between glides at low frequencies than at high frequencies. Research comparing FFRs to glides and to flat tones at various frequencies in the same listeners may be warranted to help clarify the relative contributions of frequency and onset effects, since the current experimental paradigm does not allow the two to be fully disentangled.

4.3. Horizontal versus Vertical Electrode Montage

The primary role of montage seems to be that it modulates the sensitivity of the FFR to other effects. For example, horizontal-montage recordings are stronger on average in large part because they remain more robust as frequencies increase and slopes steepen. It is noteworthy that a response recorded with a horizontal montage will emphasize the contributions of earlier auditory-system components, while a vertical montage will emphasize contributions of later ones. Table 2 illustrates the general trend for horizontal-montage stimulus-to-response lags to be shorter than vertical montage lags, which supports the idea that horizontal-montage recordings are more sensitive to earlier, more peripheral activity (also see King et al., 2016).

4.4. Significant Interactions

Several of the significant interactions we observed emphasize some of the stimulus characteristics that influence the FFR. Direction contributed to both a two-way interaction (Direction × Window) and a three-way interaction (Direction × Montage × Window) for the SRCC. When considered together, Direction and Window can be thought to roughly divide the one-octave frequency range into lower, middle, and upper regions of approximately octave each. The Direction × Window interaction, then, coarsely represents a main effect of stimulus frequency, with about a -octave resolution. The lowest frequency region of rising glides is in the first window (0–40 ms), whereas for falling glides it occurs in the third window (80–120 ms). Over the range of frequencies considered in this study (354–707 Hz), the lowest frequencies produced notably stronger correlations than the middle and upper portions of the frequency range. Similarly, the Direction × Montage × Window interaction can perhaps be viewed more meaningfully as a Montage × Frequency interaction: recordings obtained from the vertical montage are more sensitive to stimulus frequency than are those from the horizontal montage; thus, the vertical montage is the primary driver of the Direction × Window effect. Although, the effect of stimulus frequency was not directly tested in this study, it can be reasonably inferred from Figure 5 where results are plotted according to average window frequency.

The Montage × Window interaction for the SRCC also reflects the influence of frequency, but presents a different pattern altogether. For the vertical montage, the average correlation in the second window (40–80 ms) is lower than in the first and third windows, whereas for the horizontal montage it is higher. As noted above, in the vertical montage the lowest frequencies result in the highest correlations. These lowest frequencies occur in the first window in the rising conditions and in the last window in the falling conditions, but they never occur in the second window. Correlations are therefore lower for the second window on average, because the optimal frequencies are never presented there. In contrast, for the horizontal montage it is the highest frequencies that stand out as weaker than the rest, so the same logic operates in reverse fashion: the second window is the only time-frame where the high frequencies never occur, so it retains the strongest average correlations. Because the horizontal montage is less sensitive to frequency effects than the vertical montage, its second-window increase is smaller than the vertical montage’s second-window decrease. It should be noted that using a different frequency range for the glide stimuli may alter the pattern of interactions from what has been observed here.

Finally, there is also a significant Extent × Montage × Window interaction, which simply reflects that frequencies that are further apart from one another result in more pronounced differences. The nature of the differences, however, is exactly the same as for the Montage × Window interaction.

4.5. SNR and SRCC Response Measures

Although most of the response patterns and trends discussed above are relatively consistent between the SNR and SRCC measures, there are at least two notable differences. First, the onset effect (the early enhancement of vertical-montage responses to rising tones) primarily manifests as a large boost in SNR in the first window, while similar increases to SRCC are absent. SNR is an estimate of the magnitude of the response in a given frequency region of the stimulus; SRCC is an estimate of the covariance between the phase of the response and the phase of the stimulus. Interestingly, the increase in onset magnitude in the FFR does not translate into a better temporal coherence between stimulus and response; rather, the temporal coherence is more closely related to stimulus frequency (see Figure 5).

Second, the SNR is substantially more variable than the SRCC. The methodological differences in calculation of the two measures introduce at least three potential sources of additional variability into the SNR that are not present for the SRCC: (1) The SNR is derived from two variable components—signal and noise—whereas the SRCC has only one (the response varies across subjects but the stimulus does not). (2) Broadband changes in amplitude systematically coinciding with stimulus-on periods or stimulus-off periods will show up as changes in SNR but not as changes in SRCC. This is because the reference window for the noise floor is a stimulus-off period, while the signal is calculated from stimulus-on periods. Therefore, from the standpoint of this particular SNR measure, broadband stimulus-related changes in magnitude are indistinguishable from changes that are specific to the frequencies near those of the stimulus. (3) The Blackman functions used to window the responses for SNR analysis are heavily time-weighted to the center of each window. While this has the advantage of isolating a very short time-fragment from the moving signal to allow for defining a target frequency, it also has the side-effect of reducing the amount of data being used to obtain the measurement. The SRCC, on the other hand, does not require any windowing, because it does not involve finding spectral peaks. Thus, data were averaged more uniformly within each window, which tends to reduce variability.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated neural coding of dynamic spectral changes in tone glides that varied in direction and extent of frequency change. Responses recorded with vertical and horizontal montages were compared to one another to contrast the encoding of dynamic spectral information at relatively lower and higher levels of the brainstem. On average, weaker neural responses were observed in response to tone glides with larger frequency extents (i.e., faster rates of frequency change), but no difference was noted between upward- and downward-sloping glides. Neural responses at lower-frequencies (<~500 Hz) tended to be more robust than at higher frequencies, particularly with a vertical recording montage. These results suggest that the FFR is well suited to evaluating neural coding of dynamic spectral change in simple tonal stimuli, and that different electrode montages may emphasize different signal characteristics. Future studies will apply these methods to more natural speech-like stimuli and impaired populations to determine how neural coding may differ for complex speech signals and in individuals with potential processing deficits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD R01DC12314 (MRM) and R01DC015240 (CJB). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the NIH or US government. Portions of this work were presented at the 2016 American Auditory Society Annual Scientific and Technology Meeting. Special thanks to Sam Gordon and Drs. Melissa Frederick, Sean Kampel, and Jane Grabowski for their assistance with this project.

References

- Abrams DA, & Kraus N (2009). Auditory pathway representations of speech sounds in humans Issues in Hand Book of Clinical Audiology, (pp. 611–676). [Google Scholar]

- Aiken SJ, & Picton TW (2008a). Envelope and spectral frequency-following responses to vowel sounds. Hearing Research, 245, 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken SJ, & Picton TW (2008b). Human cortical responses to the speech envelope. Ear and Hearing, 29, 139–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlinger S, Jerlvall L, Ahren T, & Holmgren E (1977). Thresholds forlinear frequency ramps of a continuous pure tone. Acta Otolaryngologica, 83, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra R, Kuwada S, & Maher VL (1986). The frequency-following responseto continuous tones in humans. Hearing Research, 21, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran B, & Kraus N (2010). The scalp-recorded brainstem responseto speech: Neural origins and plasticity. Psychophysiology, 47, 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinard CG, & Cotter CM (2015). Neural representation of dynamicfrequency is degraded in older adults. Hearing Research, 323, 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey EB, Herholz SC, Chepesiuk AM, Baillet S, & Zatorre RJ(2016). Cortical contributions to the auditory frequency-following responserevealed by MEG. Nature Communications, 7, 11070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MJ, & Cullen JK Jr (1978). Temporal integration of tone glides.The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 63, 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau T, Wegner O, Mellert V, & Kollmeier B (2000). Auditory brainstemresponses with optimized chirp signals compensating basilar-membrane dispersion.The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 107, 1530–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easwar V, Banyard A, Aiken S, & Purcell D (2018). Phase delays betweentone pairs reveal interactions in scalp-recorded envelope following responses.Neuroscience Letters, 665, 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott LL, Hammer MA, Scholl ME, Carrell TD, & Wasowicz JM (1989). Discrimination of rising and falling simulated single-formant frequency transitions: practice and transition duration effects. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 86(3), 945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith GC (1994). Two-channel brain-stem frequency-following responsesto pure tone and missing fundamental stimuli. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section, 92, 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith GC, Threadgill MR, Hemsley J, Salour K, Songdej N, Ton J, & Cheung L (2000). Putative measure of peripheral and brainstemfrequency-following in humans. Neuroscience Letters, 292, 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M, & Poeppel D (2001). Inequality in identification of directionof frequency change (up vs. down) for rapid frequency modulated sweeps.Acoustics Research Letters Online, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse SW, & Geisser S (1959). On methods in the analysis of profiledata. Psychometrika, 24, 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Keselman H, & Keselman JC (1993). Analysis of repeated measurements Applied analysis of variance in behavioral science, (pp. 105–145). [Google Scholar]

- King A, Hopkins K, & Plack CJ (2016). Differential group delay of thefrequency following response measured vertically and horizontally. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 17, 133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Swaminathan J, Gandour JT (2009). Experience-dependent enhancement of linguistic pitch representation in the brainstem is not specific to a speech context. J Cogn Neurosci, 21(6), 1092–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, & Parkinson J (2000). Human frequency-following response:representation of tonal sweeps. Audiology and Neurotology, 5, 312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwada S, Batra R, & Maher VL (1986). Scalp potentials of normal andhearing-impaired subjects in response to sinusoidally amplitude-modulatedtones. Hearing Research, 21, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiste A, & Picton T (1989). Human auditory evoked potentials tofrequency-modulated tones. Ear and Hearing, 10, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J, Brown W, & Smith J (1974). Differential brainstem pathways forthe conduction of auditory frequency-following responses. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 36, 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauchly JW (1940). Significance test for sphericity of a normal n-variate distribution. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 11, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner LR, Schafer RW et al. (2007). Introduction to digital speech processing. Foundations and Trends in Signal Processing, 1, 1–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rupert A, Moushegian G, & Galambos R (1963). Unit responses to soundfrom auditory nerve of the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology, 26, 449–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SE, & Nuttall AL (1985). High-synchrony cochlear compound actionpotentials evoked by rising frequency-swept tone bursts. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 78, 1286–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoe E, & Kraus N (2010). Auditory brainstem response to complex sounds:a tutorial. Ear and Hearing, 31, 302–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan J, Krishnan A, Gandour JT, & Xu Y (2008). Applicationsof static and dynamic iterated rippled noise to evaluate pitch encoding in thehuman auditory brainstem. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 55, 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasaki I (1954). Nerve impulses in individual auditory nerve fibers of guinea pig. Journal of Neurophysiology, 17, 97–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wieringen A, & Pols LC (1994). Frequency and duration discrimination of short first-formant speechlike transitions. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 95(1), 502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.