Summary

The root lesion nematode P ratylenchus zeae, a migratory endoparasite, is an economically important pest of major crop plants (e.g. cereals, sugarcane). It enters host roots, migrates through root tissues and feeds from cortical cells, and defends itself against biotic and abiotic stresses in the soil and in host tissues. We report de novo sequencing of the P . zeae transcriptome using 454 FLX, and the identification of putative transcripts encoding proteins required for movement, response to stimuli, feeding and parasitism. Sequencing generated 347 443 good quality reads which were assembled into 10 163 contigs and 139 104 singletons: 65% of contigs and 28% of singletons matched sequences of free‐living and parasitic nematodes. Three‐quarters of the annotated transcripts were common to reference nematodes, mainly representing genes encoding proteins for structural integrity and fundamental biochemical processes. Over 15 000 transcripts were similar to C aenorhabditis elegans genes encoding proteins with roles in mechanical and neural control of movement, responses to chemicals, mechanical and thermal stresses. Notably, 766 transcripts matched parasitism genes employed by both migratory and sedentary endoparasites in host interactions, three of which hybridized to the gland cell region, suggesting that they might be secreted. Conversely, transcripts for effectors reported to be involved in feeding site formation by sedentary endoparasites were conspicuously absent. Transcripts similar to those encoding some secretory–excretory products at the host interface of B rugia malayi, the secretome of M eloidogyne incognita and products of gland cells of H eterodera glycines were also identified. This P . zeae transcriptome provides new information for genome annotation and functional analysis of possible targets for control of pratylenchid nematodes.

Keywords: nematode effectors, parasitism genes, Pratylenchus spp., root lesion nematode, transcriptome

Introduction

Pratylenchus zeae is a migratory endoparasitic root lesion nematode (RLN) present in many agricultural regions. It can infect major economically important crops, such as cereals, fruits and vegetables, cotton, coffee and sugarcane, so contributing to substantial yield losses (Blair and Stirling, 2007; Castillo and Vovlas, 2007). Pratylenchus zeae infestation is characterized by plant stunting, wilting, premature leaf yellowing, poor root development and the presence of brown lesions on roots. These symptoms result from root damage, causing nutritional and water stress, and from physical damage caused by nematode migration and feeding. Root damage also enables other soil microorganisms and root pathogens to enter (Khan, 1959). The control of plant‐parasitic nematodes (PPNs) normally involves resistance breeding, cultural practices or the application of chemical nematicides: for broad‐scale agriculture, chemical control is usually uneconomical, and many of the older nematicides have now been banned or their use restricted because of environmental and human risk concerns (Chitwood, 2002). This has prompted a search for alternative methods of control, including biological control agents, more environmentally benign chemicals or new forms of genetic control. The delivery of compounds that prevent the growth of PPNs via transgenic plants is one such approach, e.g. by expressing proteins that inhibit nematode behavioural or digestive functions, or RNA interference (RNAi) to inactivate genes vital for nematode parasitism or metabolism. The identification of suitable target genes for such control strategies requires a detailed knowledge of the genes present and their function, which, until recently, has been lacking (Fosu‐Nyarko and Jones, 2015; Jones and Fosu‐Nyarko, 2014).

The life cycle of Pratylenchus species varies from 3 to 8 weeks depending on the conditions and host (Castillo and Vovlas, 2007). Pratylenchus zeae reproduces by parthenogenesis: adult females lay eggs singly or in small groups; first‐stage juveniles (J1) develop in the eggs and moult to the first infective J2 stage, followed by three further moults (to J3, J4 and adults). All stages from J2s to adults are vermiform and motile, can leave and enter roots, and can feed from host cells (Jones and Fosu‐Nyarko, 2014; Stirling, 1991). They locate host roots via gradients in the soil rhizosphere (Trevathan et al., 1985), then enter the roots, move from cell to cell and feed from cell cytoplasm using their mouth stylet. Feeding is accompanied by mechanical probing and the secretion of compounds and effectors from gland cells, chemosensory sensilla and amphids (Perry, 1996; Reynolds et al., 2011; Zunke, 1990).

Partly because RLNs do not induce permanent feeding sites, such as giant cells, syncytia or nurse cells (Jones, 1981), which enable infection sites of sedentary endoparasites to be identified readily, host–pathogen studies of RLNs have been neglected despite their economic importance. With new genomic technologies this situation is now changing, and it is evident that RLNs are amenable to RNAi: the down‐regulation of genes required for movement significantly decreases their survival and reproduction (Soumi et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2013). RNAi studies in PPNs have two complementary roles: to study gene function and to define targets for an RNAi strategy to control them. As RLNs actively seek and feed from host cells throughout their lives, the genes required for locomotion, neuro‐reception (e.g. chemo‐ and thermo‐reception) and successful parasitism are expressed in all infective stages, making them good subjects for functional studies. However, to date, there has been no work to identify and analyse such transcripts/genes for P. zeae. Here, we report the sequencing and analysis of the transcriptome of mixed stages of P. zeae to identify transcripts for proteins that make them successful parasites. These include transcripts for proteins similar to those required for movement and response to stimuli in other nematodes, and putative transcripts encoding effectors similar to those secreted from gland cells by other PPNs. Such effectors may modify cell walls, aid the ingestion and digestion of host cell cytoplasm, and enable the parasites to evade or neutralize host immune responses. The identification and functional analysis of such transcripts are needed to understand why RLNs are widespread and successful crop pests, and how their genome complement and secreted effectors function and differ from those of sedentary endoparasites. This knowledge will contribute to the development of new strategies for genetic or chemical control of these important agricultural pests (Fosu‐Nyarko and Jones, 2015).

Results

P ratylenchus zeae transcriptome

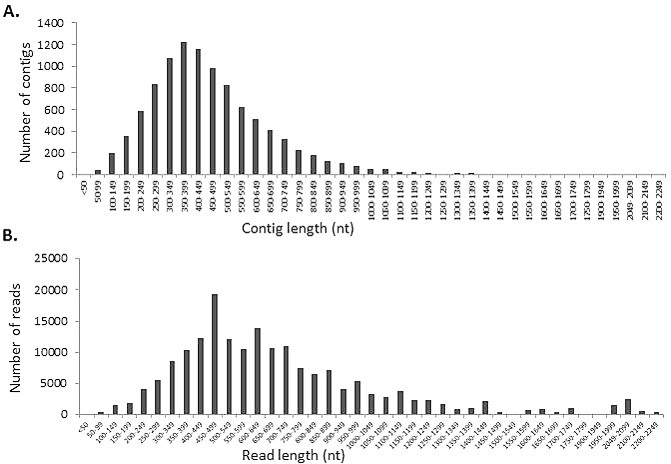

Sequencing of the transcriptome of motile J2 to adult stages of P. zeae yielded 347 443 high‐quality reads: over 98% had an average PHRED score of 22 or more. The reads consisted of 32 602 958 nucleotides with a mean read length of 178.8 nucleotides, 60% (208 429) of which were assembled using SoftGenetics NextGEne V2.16 into 10 163 contigs with an average of 17.9 reads/contig. The minimum number of reads/contig was two and the maximum was 5746 (for contig 251 which wa 450 nucleotides long); 11 other contigs were composed of a similar number of reads. The contigs ranged in size from 16 to 2221 nucleotides with an average of 470.5 nucleotides and an N50 of 519 bases. About 72% of the contigs were of size 200–599 nucleotides, with the highest number between 300 and 399 nucleotides (Fig. 1). The singletons (139 015 of the reads not used in contig assembly) ranged from 40 to 752 nucleotides, with an average length of 182 nucleotides. The A + T contents of contigs and singletons were 53.9% and 55.3%, respectively. Transcripts less than 100 nucleotides in length (53 contigs and 46 044 singletons) were excluded from functional analyses. The reads and assembled transcripts were deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject ID PRJNA268047, with the accession number SRR1657910 for deposits in the Sequence Read Archive and temporary BioSample submission ID, and SUB990140 for the assembled transcripts in the Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly database.

Figure 1.

Sequence characteristics of the P ratylenchus zeae transcriptome. (A) Distribution of contig lengths. (B) Distribution of read lengths. nt, nucleotides.

Analysis of transcripts putatively encoding carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes) and identification of possible contamination

Considerable care was taken to prevent possible contamination of the starting material and during the sequencing process, as this can be an issue for high‐throughput sequencing data (Lusk, 2014). Possible contamination in the P. zeae transcriptome was investigated using Alien Index (AI) analysis as described by Gladyshev et al. (2008) and Eves‐van den Akker et al. (2014). To do this, AI was calculated for all transcripts (singletons and contigs) that returned a blastx hit to at least a sequence of a metazoan or non‐metazoan species in the NCBI non‐redundant nr/nt database at an E‐value threshold of 1E‐05. An AI was not calculated for transcripts without a hit to a sequence in the database. Transcripts with AI > 0 indicated a better hit to a non‐metazoan species than to a metazoan species: these were considered as possible contaminants and, on this basis, 796 of these, including 64 contigs, were excluded from further analysis. This analysis was particularly important before comparison of the transcripts with CAZymes in the CAZy database (http://www.cazy.org), which also contain CAZymes of bacterial and fungal origin.

The recent compilations of sequences of CAZymes (CAZy database; November, 2014), which contained 188 123 protein sequences of families of glycoside hydrolases (GHs), including carbohydrate‐binding modules (CBMs), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), carbohydrate esterases (CEs) and auxiliary activities (AA), were downloaded and, together with the sequences of 500 glycosyltransferases (GTs), were compared with the P. zeae transcripts using a local blastx on CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5. At thresholds of 1E‐05, E‐value and blast hit percentage identity of 50 646 transcripts were identical to known CAZymes. For any transcript with similarity to CAZymes of both metazoans and non‐metazoans, a further filter was used to assess its possible ‘foreignness’ to the transcriptome. For this, if a transcript had ≥50% blastx hit identity to a non‐metazoan sequence, but less than 40% identity to any nematode sequence, it was excluded from the analysis. This resulted in the identification of 607 transcripts with matches to sequences of the following families of CAZymes: 20 GHs, one PL3, four CBMs, two CEs, 33 GTs and no AAs (Table S1, see Supporting Information). A majority of the transcripts matched CAZymes of both parasitic and free‐living nematodes (FLNs), mainly Caenorhabditis elegans, Strongyloides ratti and Ascaris suum, and were identified as involved in common molecular processes of development, e.g. endoplasmic reticulum degradation‐enhancing α‐mannosidase, trehalases and lysozymes (Table S1).

Sixty‐three P. zeae transcripts matched CAZymes of PPNs (Table 1). Some transcripts matched CAZymes with multiple enzyme domains of the different classes, and these were generally GHs with CBMs. For example, 27 transcripts matched GH5 cellulases of Ditylenchus destructor, Pratylenchus coffeae and Radopholus similis, and these proteins are also known to have CBM2 activity (Table 1). A total of 45 transcripts matched GH5 cellulases of five genera of PPNs: these were Pratylenchus species (P. penetrans, P. pratensis, P. vulnus and P. coffeae), the lesion nematode R. similis, Aphelenchoides fragariae, Rotylenchulus reniformis and D. destructor. Two transcripts were also similar to those of PL3 pectate lyases of the cyst nematodes Heterodera schachtii and H. glycines. Together with GH5 cellulases, pectate lyases are well‐characterized cell wall‐modifying enzymes secreted from gland cells of PPNs during the migration phase of host invasion (Smant et al., 1998).

Table 1.

P ratylenchus zeae transcripts putatively encoding carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes) similar to those of plant‐parasitic nematodes

| CAZy family | CAZymes putatively encoded by P. zeae transcripts | Number of matching transcripts | blastx characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism with best CAZyme match | NCBI accession number of CAZyme with greatest blastx % identity | Lowest E‐value | Greatest blastx hit identity (%) | Greatest positive (%) to best‐matching accession number | |||

| GH5 | Cellulase, partial | 1 | Aphelenchoides fragariae | AFI63769 | 4.89E‐18 | 80.56 | 94.44 |

| GH5 | β‐1,4‐Endoglucanase | 2 | Pratylenchus penetrans | BAB68523 | 1.76E‐06 | 69.57 | 86.96 |

| GH5 | β‐1,4‐Endoglucanase, partial | 5 | Pratylenchus pratensis | AER27775 | 1.26E‐11 | 83.33 | 95.83 |

| GH5 | β‐1,4‐Endoglucanase, partial | 7 | Pratylenchus vulnus | AER27785 | 1.85E‐07 | 94.12 | 100 |

| GH5 | GHF5 β‐1,4‐endoglucanase | 3 | Rotylenchulus reniformis | ADM72857 | 1.59E‐08 | 90 | 100 |

| GH5, CBM2 | β‐1,4‐Endoglucanase | 15 | Ditylenchus destructor | ADW77528 | 1.05E‐17 | 53.85 | 72.31 |

| GH5, CBM2 | GHF5 endoglucanase precursor | 9 | Pratylenchus coffeae | ABX79356 | 7.35E‐24 | 95.35 | 96.3 |

| GH5, CBM2 | GHF5 endo‐1,4‐β‐glucanase precursor | 3 | Radopholus similis | ABV54446 | 6.73E‐11 | 50 | 75 |

| PL3 | Pectate lyase | 2 | Heterodera glycines, Heterodera schachtii | ADW77534; ABN14273 | 8.54E‐08 | 69.77 | 79.07 |

| GT20 | Putative trehalose 6‐phosphate synthase | 15 | Aphelenchus avenae | CAH18869; CAH18871; CAH18873; CAH18874 | 1.95E‐73 | 96.29 | 94.73 |

| GT2 | Chitin synthase | 1 | Meloidogyne artiellia | AAG40111 | 1.09E‐10 | 83.33 | 84 |

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information.

A total of 52 transcripts best matched the GH family of CAZymes of six non‐nematode origins: Oryza sativa and O. indica, the bacterium Peptoclostridium difficile and fungi Piriformospora indica and Leptosphaeria maculans, and the insect Nilaparvata lugens. Further analyses of these transcripts indicated that they also had ≥40% identity to similar nematode proteins. For example, the GH18 protein LEMA_P082410.1 of L. maculans JN3, whose transcripts are putatively similar to 32 transcripts of P. zeae, also had 55% sequence identity to protein kinases of both free‐living and parasitic nematodes, including Caenorhabditis japonica, Pristionchus pacificus, Brugia malayi and Haemonchus contortus.

The majority (75%) of the 344 transcripts matching the 34 GT families were mainly those of the nematodes C. elegans and A. suum, and are required for common biological or developmental processes (Table S1). The best matches to PPNs included GT2 chitin synthase of the root knot nematode Meloidogyne artiellia and GT20 putative trehalose 6‐phosphate synthase of Aphelenchus avenae. In addition, there were matches to exostosin‐1 and ‐2 (of A. suum), an endoplasmic reticulum‐resident type II transmembrane GT involved in the biosynthesis of heparan sulfate. Interestingly, there were transcripts similar to those encoding bre‐3 and bre‐4 of C. elegans and bre‐4 and bre‐5 of A. suum, which encode GT2 β‐1,4‐mannosyltransferases, and, in the case of C. elegans, are expressed in the gut epithelium and are required for resistance to toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5B (Marroquin et al., 2000). For 69 transcripts, the best matching GT CAZymes were of non‐nematode origin; however, they also had ≥40% blastx hit identity to several similar nematode proteins.

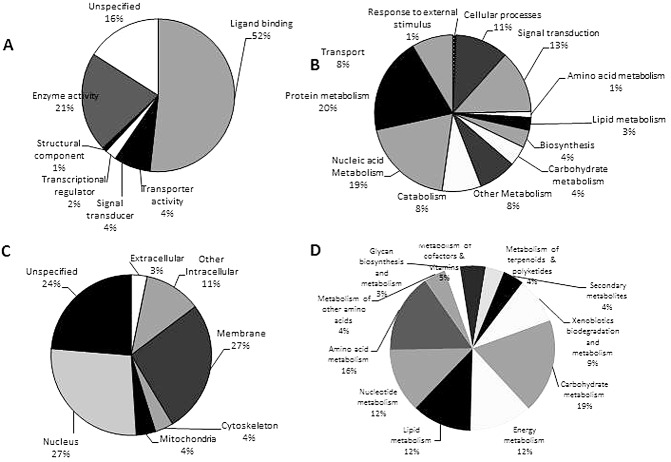

In silico functional annotation of transcripts

About 48% of contigs and 15% of singletons were assigned putative functions from their similarities to genes encoding proteins involved in biological, molecular and/or cellular processes using the Gene Ontology (GO) classification and genetic information from C. elegans. These (4827 contigs and 21 129 singletons) matched genes associated with 912 GO terms, including 420 multiple terms associated with biological functions, 321 terms with molecular functions and 171 terms with cellular functions (Fig. 2). A total of 52% of the transcripts had putative molecular functions associated with ligand binding—a term which describes how molecules, including secreted peptides (activators and repressors), may interact with each other or with receptors. The most highly represented GO category under biological processes was metabolism, associated with 65% of the transcripts, including 21% each for protein and nucleic acid metabolism. Transcripts putatively encoding nuclear or membrane proteins, or associated with genes that encode proteins with similar functional domains, were also identified. Some transcripts (24% in the cellular component and 16% in the molecular category) had unspecified functions. All categories in the GO scheme necessary for eukaryotic development were represented in the transcriptome.

Figure 2.

Functional classification of P ratylenchus zeae transcripts. (A) Percentage of transcripts mapping to Gene Ontology (GO) terms with molecular functions. (B) Percentage of transcripts matching terms for biological processes. (C) Percentage of transcripts matching terms with cellular components. (D) Classification of transcripts into biochemical pathways using Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

Using Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) metabolic pathways, 9411 contigs and singletons were assigned Enzyme Commission (EC) and KEGG Ontology (KO) numbers, and represented 11 major metabolic EC pathways (Fig. 2). A similar number of transcripts matched enzymes involved in nucleotide, lipid and energy metabolic pathways, and slightly more were assigned to pathways for amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 2). About 9% of the transcripts were similar to genes involved in xenobiotics, biodegradation and metabolism.

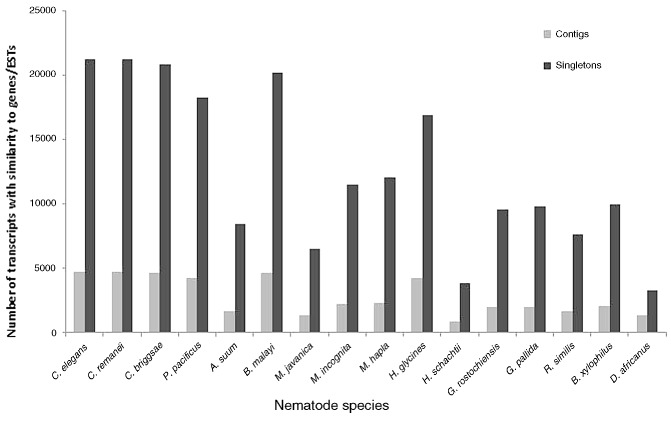

Similarity to expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and genes of other nematodes

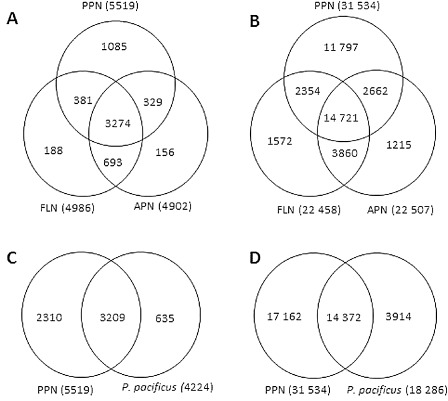

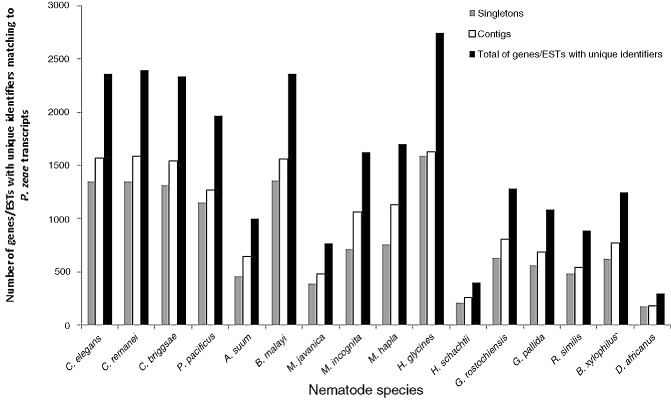

The P. zeae transcripts were further annotated by comparison with sequences of a reference group of 16 nematode species with different modes of feeding and lifestyle. These included three FLNs (C. elegans, C. remanei and C. briggsae), two animal‐parasitic nematodes (APNs; A. suum and B. malayi), the insect nematode P. pacificus and 10 species of PPNs [three root knot nematodes (Meloidogyne incognita, M. hapla, M. javanica), four cyst nematodes (H. glycines, H. schachtii, Globodera pallida, G. rostochiensis), the migratory endoparasite R. similis, the peanut pod nematode D. africanus and the pine wilt nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus]. Using a tblastx search to compare the transcripts with individual sequence databases of the reference nematodes on NCBI at an E‐value threshold of 1E‐05, 6473 contigs and 38 181 singletons were similar to sequences of at least one of the nematode species (Fig. 3). For each reference group, there were consistently more singletons with identity to reference sequences than to contigs. The large number of database sequences for B. malayi (compared with A. suum) and H. glycines (compared with the other PPNs) is reflected in the greater number of matches of P. zeae transcripts to these species (Fig. 3). Venn diagrams were constructed for the distribution of transcripts among different nematodes, which allocated the transcripts into those that matched sequences of the reference nematodes. Of the annotated transcripts, 3274 contigs and 14 721 singletons were similar to genes/ESTs of nematodes of all lifestyles (Fig. 4). Overall, more transcripts matched ESTs of PPNs than the three well‐characterized Caenorhabditis spp. There were 1570 contigs and 15 674 singletons with high similarity to sequences of PPNs, which had no match to any sequence of the FLNs or P. pacificus: some of these could represent genes needed for parasitism.

Figure 3.

P ratylenchus zeae transcripts matching genes/expressed sequence tags (ESTs) of 16 nematode species.

Figure 4.

Distribution of P ratylenchus zeae transcripts among free‐living nematodes (FLNs), animal‐parasitic nematodes (APNs), plant‐parasitic nematodes (PPNs) and P ristionchus pacificus. (A, B) Number of P . zeae contigs (A) and singletons (B) with matches to genes/expressed sequence tags (ESTs) of FLNs, APNs and PPNs. (C, D) Number of P . zeae contigs (C) and singletons (D) with similarities to P . pacificus genes. FLNs: C aenorhabditis elegans, C . briggsae, C . remanei. APNs: A scaris suum, B rugia malayi. PPNs: H eterodera glycines, H . schachtii, G lobodera pallida, G . rostochiensis, M eloidogyne incognita, M . hapla, M . javanica, R adopholus similis, B ursaphelenchus xylophilus, D itylenchus africanus.

tblastx alignment scores (total bit scores) for the annotated transcripts (E‐value of 1E‐05) ranged from 30 to over 4000. In general, for matches to the nematode species, 40%–50% of the annotated contigs had total bit scores of ≥100, whereas more matching singletons (>60%) had scores of <100. For example, of the 4758 transcripts with matches to genes of the three Caenorhabditis spp., 2070 had total bit scores of ≥100, whereas only 15% of the >21 000 singletons had total bit scores of ≥100. Unique genes expressed in the transcriptome were determined from the tblastx homologues using a total bit score of 100 as the threshold. The results are shown in Fig. 5, which indicates the number of matching genes/ESTs for each of the nematode reference groups and the number of genes/ESTs with unique identifiers for both transcripts. Generally, for each reference nematode, more hits/genes were identical to singletons than to contigs. However, the numbers of ESTs/genes with unique identifiers matching either transcript were similar, indicating that most singletons were fragments of the same genes but lacked sufficient overlapping sequences to create contigs. To verify this observation, the reads were also assembled with CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5 and GS De novo Assembler (Newbler) Version 2.5 using similar parameters of minimum overlap length and identity of 40% and 90%, respectively, and the transcripts were compared with C. elegans proteins using a local blastx with an E‐value threshold of 1E‐05. The assembly generated 67 849 contigs and 38 960 singletons from the CLC Genomics Workbench, and 13 771 contigs and 13 938 singletons by Newbler. For both sets of assemblies, some contigs and singletons were identical to transcripts of the same C. elegans proteins: 905 singletons of the CLC Genomics Workbench assembly were identical to transcripts of the same proteins matching 2461 contigs and 190 Newbler singletons, and 554 contigs were identical to transcripts of the same C. elegans proteins, indicating that, for some genes, the read coverage was not sufficient for complete assembly.

Figure 5.

Number of genes/expressed sequence tags (ESTs) with unique identifiers of 16 different nematodes matching transcripts of P ratylenchus zeae (total bit score of >100).

For the three Caenorhabditis spp., the NextGEne contigs matched 1354 genes (bit score of >100), whereas the singletons matched 1584 genes, which together represented a total of 2396 homologues (genes) with unique Wormbase identifiers. Transcripts identical to 1746 unique H. glycines ESTs (with a bit score of >100) were identified in the transcriptome—more than for any other nematode species (Fig. 5). The Caenorhabditis spp. analysis was performed on unique genes, whereas, for PPNs and APNs, the analysis was performed with ESTs, and so the number of genes identified may have been overestimated, because of redundancy in EST databases. Most of the common genes/ESTs similar to sequences of all the reference nematodes were involved in fundamental biological and molecular processes related to different aspects of development (Table 2).

Table 2.

P ratylenchus zeae transcripts with best matches to 10 common genes of nematodes with different lifestyles

| Gene description | Wormbase Gene ID | Number of matching contigs, singletons | Length of longest contig (nucleotides) | Total bit scores of longest contig to genes of nematode species | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caenorhabditis elegans | Brugia malayi | Pristionchus pacificus | Meloidogyne incognita | Heterodera glycines | ||||

| Heat shock hsp70 proteins | WBGene00009692 | 2, 3 | 1301 | 994 | 895 | 771 | 1041 | 932 |

| Actin‐related protein of the conserved Arp2/3 complex (arx‐4) | WBGene00021170 | 1, 1 | 925 | 1221 | 414 | 972 | 1168 | 1059 |

| Protein kinase N (pkn‐1) | WBGene00009793 | 1, 10 | 1055 | 1330 | 438 | 228 | 1068 | 804 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) iron–sulfur protein (dhb‐1) | WBGene00006433 | 1, 3 | 926 | 1294 | 403 | 692 | 1586 | 1593 |

| Guanine nucleotide‐binding protein (goa‐1) | WBGene00001648 | 3, 13 | 921 | 1582 | 335 | 1299 | 1843 | 1076 |

| Actin (act‐2) | WBGene00000064 | 2, 16 | 864 | 1664 | 1079 | 1472 | 1522 | 1848 |

| Casein kinase I (kin‐19) | WBGene00002202 | 4, 14 | 1383 | 1491 | 498 | 903 | 1197 | 1414 |

| ATP‐dependent DEAD‐box RNA helicase (cgh‐1) | WBGene00000479 | 2, 9 | 771 | 1378 | 447 | 1247 | 205 | 1114 |

| Casein kinase (kin‐3) | WBGene00002191 | 1, 4 | 1224 | 1153 | 1202 | 1279 | 1478 | 798 |

| Chemokine (C–C motif) receptor 4 (ccr‐4) | WBGene00000376 | 3, 5 | 1264 | 1793 | 592 | 154 | 770 | 1188 |

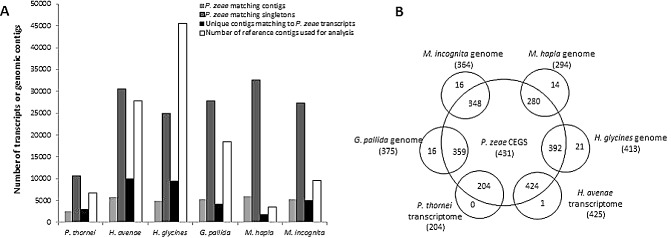

Comparative analysis with transcriptomes and genomes of PPNs

To extend the depth of the analysis, the transcripts were also compared directly and indirectly [using the Core Eukaryotic Genes (CEGs) employed for CEGMA (Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach)] with the Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA) of Pratylenchus thornei (Nicol et al., 2012), contigs of the H. avenae transcriptome (Kumar et al., 2014) and genomic sequences of M. hapla (PRJNA29083), M. incognita (PRJEA28837), H. glycines (PRJNA28939) and G. pallida (PRJEB123) available at NCBI. Using a local tblastx with a cut‐off E‐value of 1E‐05 with individual sequence databases for each reference nematode, 9% of the P. zeae transcripts (2631 contigs and 13 349 singletons) were similar to 46% (3122 of 6733) of the P. thornei TSA, whereas between 20% and 26% were similar to contigs of the other five PPNs (Fig. 6A). A higher percentage of contigs of M. hapla (54%), M. incognita (53%) and TSA of P. thornei (46%) were similar to P. zeae transcripts, compared with 36%, 24% and 21% for the cyst nematodes H. avenae, G. pallida and H. glycines, respectively (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis of P ratylenchus zeae transcripts with transcriptomes and genomes of six plant‐parasitic nematodes (PPNs). (A) tblastx matches of P . zeae transcripts to Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA) of P . thornei, transcriptome of H eterodera avenae and genomic contigs of H . glycines, G lobodera pallida, M eloidogyne incognita and M . hapla. (B) Comparison of homologues of Core Eukaryotic Genes (CEGs) in the transcriptomes of P . zeae, P . thornei, H . avenae and genomes of H . glycines, G . pallida, M . incognita and M . hapla.

In addition, the 2748 protein sequences of the euKaryotic clusters of Orthologous Groups (KOGs), representing 458 CEGs conserved between Arabidopsis thaliana, C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, Homo sapiens, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (http://korflab.ucdavis.edu/datasets/cegma), were compared with local databases of transcripts and genomes of the six nematodes above using blastx with an E‐value threshold of 1E‐05 to assess the similarity of the genomes to genes expressed in the P. zeae transcriptome. Similarities to a total of 454 of the 458 CEGs were identified in sequences of the six nematodes (Table S2, see Supporting Information). For the P. zeae transcriptome, 7% of contigs (735) and 2.51% of singletons (3496) were similar to a total of 431 CEGs (Fig. 6B). A relatively higher percentage of contigs of M. hapla (15.3%) and M. incognita (12%) were similar to 294 and 364 CEGs, respectively. Between 3% and 9% of contigs of the cyst nematodes and 5% of TSA of P. thornei were similar to the number of CEGs identified (Fig. 6B). In all, 210 CEGs were common to sequences of all the nematode species under study. Transcripts of 23 CEGs were not present in the P. zeae transcriptome, but appear to be present in the genome of at least one of the other nematodes, and genes for seven of these were present in genomic contigs of root knot and cyst nematodes.

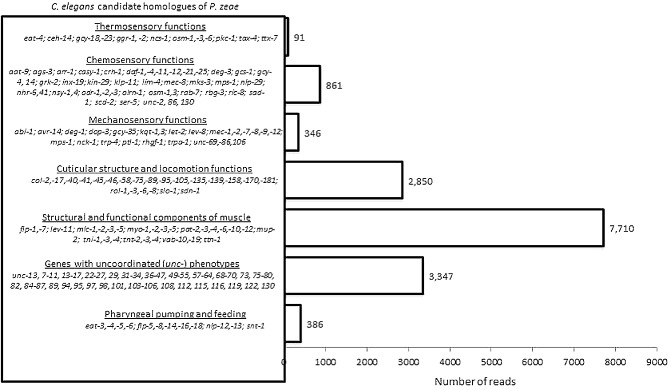

Putative thermosensory, chemosensory and mechanosensory transcripts

Caenorhabditis elegans can detect and respond to temperature changes and gradients as it moves and feeds. Little is known about the orthologous genes involved in such activities in PPNs and, for these obligate biotrophs, thermotaxis could play a role in migration through the soil and identification of a host root. From comparative analysis using 26 C. elegans genes with thermosensory and thermotactic functions, we found that 12 were similar to 91 P. zeae reads (Fig. 7). Among these were ttx‐7 (myo‐inositol monophosphatase), two guanylyl cyclases (gcy‐18, gcy‐23) and two members of the γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA)/glycine receptor family of ligand‐gated chloride channels (ggr‐1, ggr‐2) (Fujiwara et al., 1996; Kimata et al., 2012). In C. elegans, the gcy‐18 and gcy‐23 genes function redundantly to regulate thermotaxis (Hitoshi et al., 2006). Most of these genes are multifunctional and include tax‐4 and pkc‐1 (which encodes a serine/threonine protein kinase), both of which, in addition to controlling several behaviours, are required for sensitivity to chemicals and temperature (thermosensation) (Komatsu et al., 1996; Satterlee et al., 2004).

Figure 7.

Number of P ratylenchus zeae transcripts similar to C aenorhabditis elegans genes with roles in structural integrity of the cuticle and movement, and those involved in responses to stimuli.

Nematodes exhibit avoidance or attraction to certain chemicals, but, for PPNs, relatively little information is available. From our analysis, we identified P. zeae transcripts similar to the genes employed by C. elegans to respond to and/or regulate responses to chemical stimuli. Pratylenchus zeae contigs or singletons, or both, were similar to 44 of 74 C. elegans genes with chemosensory functions (Fig. 7). There were also matches to three C. elegans genes with ‘odorant‐response abnormal’ phenotypes (odr‐1, odr‐2 and odr‐3), all of which are required for correct functioning of the AWC‐olfactory neurons that respond to AWC‐sensed odorants (L'Etoile and Bargmann, 2000; Roayaie et al., 1998). In addition to odr‐1 (a putative guanylyl cyclase gene), transcripts similar to three other guanylyl cyclases (GCY‐4, GCY‐14 and DAF‐11, a transmembrane guanylyl cyclase) were identified: their functions are not only required for chemosensation and chemotaxis, but results from RNAi in C. elegans also indicate that the expression of daf‐11 may help nematodes to avoid volatile and non‐volatile odorants (Bargmann et al., 1993; Vowels and Thomas, 1994). Most of these genes can nullify the effects of some chemicals by modulating neuronal or mechanical movement (e.g. unc‐2) and are expressed in chemosensory interneurons. Some putative homologues have roles in avoidance or desensitization of C. elegans to chemicals and/or toxins. An example is the neuropeptide‐like protein NLP‐29, which, in C. elegans, is thought to have antimicrobial properties, as its expression, which is localized in the hypodermis and intestine, is highly up‐regulated following exposure to bacteria and fungi (Nathalie et al., 2008).

Sensory receptors are needed by soil‐inhabiting nematodes to respond to external stimuli. From comparative analysis with C. elegans genes with such roles, 346 P. zeae reads (17 contigs and 110 singletons) were similar to 24 C. elegans genes that either encode proteins with specific functional domains (e.g. Kunitz, mec‐1; Kunitz‐type protease inhibitor domains, mec‐9), structural elements (e.g. mec‐7, mec‐12) or regulatory enzymes involved in the complex process of response to touch (Savage et al., 1989). These genes are involved in mobilizing the touch receptor ‘degenerin’ complex (mec‐1, unc‐105), especially to the body wall, and in ensuring the abundance of collagen in extracellular matrices (García‐Añoveros et al., 1998). Amongst these were six genes with ‘MEChanosensory abnormality’ RNAi phenotypes encoding different genes (mec‐1, mec‐2, mec‐7, mec‐8, mec‐9, mec‐12), three genes with ‘uncoordinated’ RNAi phenotypes (unc‐69, unc‐89, unc‐105) and gcy‐35.

Guanylyl cyclases may have important functions in several processes, some multifunctional, in protecting nematodes from different forms of abiotic stress. An example is gcy‐35, which, in C. elegans, expresses in sensory neurons, pharyngeal and body wall muscles. It encodes a soluble guanylyl cyclase, which is required for the regulation of feeding and also innate immunity (Gray et al., 2004; Hukema et al., 2006). It also plays a part in sensing increasing oxygen levels and behavioural changes (Gray et al., 2004). The function(s) of such genes have not been determined in PPNs, and this analysis provides a basis for further functional characterization.

Transcripts similar to C . elegans genes required for feeding and pharyngeal pumping

A total of 386 P. zeae reads were similar to 12 C. elegans genes required for pharyngeal pumping and feeding. Of these, 214 were identical to eat‐3, eat‐4, eat‐5 and eat‐6 for which loss of function affects ‘eating’. These genes encode proteins involved in different processes in C. elegans, but are generally expressed in pharyngeal muscles and/or cells (Avery, 1993; Starich et al., 1996). An example is eat‐3, which encodes a mitochondrial dynamin required for body size development, growth, movement and reproduction. It is highly expressed in muscles and neurons, and loss of function in C. elegans results in irregular and reduced pharyngeal pumping, as do transcripts of eat‐4 (a vesicular glutamate transporter), eat‐5 (an innexin) and eat‐6 (encoding an α subunit of a sodium/potassium ATPase) (Kanazawa et al., 2008). Loss of function also affects other aspects of feeding: eat‐4 is required for chemotaxis, feeding, foraging and thermotaxis, whereas eat‐5 and eat‐6 are required for relaxation and synchronized pharyngeal muscle contractions (Lee et al., 1999; Starich et al., 1996). The roles of similar genes have not been studied in PPNs, for example, how they may affect host recognition and feeding. Pratylenchus zeae transcripts similar to C. elegans genes encoding products which regulate action potentials of pharyngeal muscles or are expressed in pharyngeal muscles or neurons were a synaptotagmin (snt‐1) and neuropeptide‐like proteins, including an LQFamide neuropeptide (nlp‐12), possibly with a role in the regulation of digestive enzyme secretion and fat storage, an MSFamide neuropeptide (nlp‐13) and five FMRFamide‐like peptides (flp‐5, flp‐8, flp‐14, flp‐16 and flp‐18): orthologues of these genes have also been identified in other PPNs (Abad et al., 2008; Maule and Curtis, 2011).

P ratylenchus zeae transcripts matching genes for locomotion

Uncoordinated (unc) mutants of C. elegans have been used to characterize over 700 genes involved in many cellular processes that regulate mechanical and neural control of movement, including myosin assembly (Hoppe and Waterston, 2000), regulation of G protein and receptor signalling (Hajdu‐Cronin et al., 1999; Koelle and Horvitz, 1996; Lackner et al., 1999; Robatzek et al., 2001), neuropeptide function (Frooninckx et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 1998) and maintenance of structure and integrity of the cuticle (Broday et al., 2007). These genes were used to identify P. zeae transcripts that may encode proteins with similar functions. About 1300 reads had high similarity to C. elegans genes involved in structural integrity of the cuticle, muscle and collagen formation and function, and directional movement (Fig. 7).

Amongst matches to genes of C. elegans were those encoding nematode cuticular collagen (e.g. col‐2, rol‐6) required for the development of normal body morphology, and those required for structural integrity, appropriate functioning and maintenance of muscle, including the troponin C and I (tnc, tni) gene families (Terami et al., 1999). There were 7710 reads matching the latter genes, including paralysed arrest at two‐fold (pat‐2, pat‐3, pat‐4, pat‐6, pat‐10, pat‐12), genes encoding heavy chain myosin (e.g. myo‐1), ttn‐1 and vab‐10. Of these, pat‐10 (alias tnc‐2) and unc‐87 (required to maintain the structure of myofilaments in body wall muscle cells) are also involved in the control of movement in RLNs: knockdown of both genes causes paralysis and strong inhibition of reproduction in host tissues (Soumi et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2013). A total of 24 contigs and 10 singletons matched ttn‐1 (a connectin), the largest known protein responsible for passive elasticity of muscle (Forbes et al., 2010). Transcripts similar to the vab‐10 gene were highly represented in the transcriptome: there were 2263 reads assembled into 17 contigs and 39 singletons. In C. elegans, vab‐10 encodes two spliceoforms of spectraplakins that act jointly to provide mechanical resilience to the epidermis under strain. RNAi phenotypes of vab‐10 show that it is essential for the organization of body wall muscles (Bosher et al., 2003; Plenefisch et al., 2000).

Transcripts with high identity to two functionally diverse neuropeptides, FLP‐1 and FLP‐7, of C. elegans were also identified. The flp‐1 gene regulates well‐coordinated sinusoidal movement and transition between active and inactive states of egg laying (Nelson et al., 1998). In contrast, FLP‐7 is a negative regulator of movement, as injection of C. elegans FLP‐7 peptides into A. suum causes paralysis and loss of locomotory waveforms (Reinitz et al., 2000). In addition, 162 contigs matched 84 ‘unc’ genes encoding proteins involved in processes for which loss of function results in aberrant movement or uncoordinated phenotypes. As well as the transcripts putatively encoding slo‐1 and sdn‐1 genes, which are required for forward and backward motion in C. elegans, functional characterization of similar genes, which could be important for mechanical and neural control of movement of migratory endoparasitic nematodes, is needed, as such genes are potential targets for the control of these pests (Carre‐Pierrat et al., 2006).

Nematode parasitism genes

There were 92 contigs and 674 singletons identified with high sequence similarity to 25 previously characterized or putative PPN parasitism genes, or those that encode proteins involved in nematode–host interactions (Table 3). Five of these genes matched only singletons and except for peroxiredoxins, both contigs and singletons were similar to genes encoding products employed by PPNs to elicit or suppress host defences: these included secreted SPRYSEC proteins of G. pallida (Sacco et al., 2009), superoxide dismutase (Zacheo and Bleve‐Zacheo, 1988; Zacheo et al., 1987), thioredoxin (Hewitson et al., 2008; Lu et al., 1998), peroxiredoxin (Li et al., 2011), glutathione peroxidase (Jones et al., 2004) and glutathione S‐transferase (Dubreuil et al., 2007). The P. zeae sequences were most similar to genes of three Meloidogyne spp., two Globodera spp., two Heterodera spp. and D. africanus, and, except for peroxiredoxin, were also similar to genes of the roundworm A. suum (Table 3). A candidate homologue of the nematode‐specific fatty acid‐ and retinol‐binding (FAR) family of proteins, secreted for the evasion of host defences, was also identified with high total alignment scores to those characterized for other PPNs. Many transcripts were identical to three well‐characterized cell wall‐degrading enzymes apparently secreted by sedentary PPNs during migration through host tissue pectate lyase, endoglucanases and polygalacturonase (Table 3). Transcripts were also identified that matched three groups of proteases secreted by nematodes of all lifestyles: these were aminopeptidase, serine protease and cathepsin B, D, S and L groups of proteases. RLNs secrete a range of proteins: some are involved in digestion and others in developmental processes (e.g. moulting); others are secreted into host cells and may be required for parasitism (e.g. influencing signalling pathways, evading host defences). Some transcripts matched genes with such functions, and these included the secreted 14‐3‐3/b protein and calreticulin of M. incognita, and annexins which also had high similarities to those of cyst nematodes (Jaubert et al., 2004, 2005; Table 3). A total of 14 contigs and 107 singletons matched the group of PPN‐specific transthyretin‐like proteins (ttl) and precursors, with the best matches to those of R. similis, for which ttl1–4 are preferentially expressed in the parasitic stages (Jacob et al., 2007).

Table 3.

P ratylenchus zeae transcripts similar to putative parasitism genes of plant‐parasitic nematodes (PPNs) and A scaris suum

| Nematode parasitism gene | Number of matching transcripts (contigs, singletons) | Length of best‐matching transcript (nucleotides) | Nematode species with matches to P. zeae transcripts (*nematode with best match to most similar transcript) | tblastx results for best‐matching transcript and accession number | Example of evidence of confirmed or suggested function/role in parasitism | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | Query coverage (%) | Accession number of best‐matching gene (length, nucleotides)* | |||||||||||||||

| Mi | Mj | Mh | Gp | Gr | Hg | Hs | Rs | Da | As | Pv | |||||||

| Sec‐2 protein | 3, 26 | 923 | + | + | + | + * | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | 1834 | 77 | BM415209 (1338) | Prior et al. (2001) |

| RANBP domains | 1, 9 | 443 | − | − | − | − | − | + * | − | − | − | − | − | 385 | 84 | CA939458.1 (484) | Sacco et al. (2009) |

| Superoxide dismutase | 2, 18 | 624 | + | − | + * | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 930 | 71 | CF803336 (469) | Bellafiore et al. (2008) |

| Thioredoxin | 7, 58 | 758 | − | + | − | − | + * | − | + | − | − | + | − | 873 | 59 | AW505887 (537) | Lu et al. (1998) |

| Ubiquitin extension protein | 2, 3 | 520 | − | − | − | − | + * | − | − | − | − | − | − | 965 | 91 | EE269774 (527) | Jones et al. (2009) |

| Transthyretin‐like protein (TTL) | 14, 107 | 455 | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + * | − | − | − | 1230 | 88 | EY190294.1 (488) | Jacob et al. (2007) |

| S‐phase kinase‐associated protein 1 (SKP‐1) | 4, 0 | 459 | + * | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 365 | 79 | CF980621.1 (652) | Gao et al. (2003) |

| 14‐3‐3b protein | 5, 27 | 618 | + | + | + | − | + * | + | + | + | + | + | − | 982 | 88 | EE267463.1 (594) | Jaubert et al. (2002b) |

| Aminopeptidase | 9, 48 | 533 | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | 997 | 81 | CA995734.1 (701) | Lilley et al. (2005) |

| Annexin | 1, 30 | 581 | + | − | + * | + | + * | + | − | − | + | + | − | 1415 | 96 | BM345703.1 (583) | Jones et al. (2009) |

| Cathepsins B, L, S, D and Z* | 12, 94 | 669 | + | + | + | + * | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 1653 | 96 | BM415989.1 (1262) | Neveu et al. (2003) |

| Cellulose‐binding protein | 1, 1 | 379 | + * | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 159 | 64 | AW828050.1 (548) | Adam et al. (2008) |

| Endoglucanases and precursors | 3, 45 | 339 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + * | 916 | 83 | CV200806.1 (507) | Smant et al. (1998) |

| Galectin | 11, 57 | 448 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + * | + | + | + | − | 1433 | 98 | CD750386.1 (508) | Dubreuil et al. (2007) |

| Glutathione peroxidase | 3, 25 | 775 | + * | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | 906 | 50 | AW829298.1 (537) | Jones et al. (2004) |

| Glutathione S‐transferase | 4, 51 | 448 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + * | + | + | − | 1191 | 91 | EY194552.1 (613) | Dubreuil et al. (2007) |

| Calnexin/calreticulin | 0, 11 | 390 | + | − | − | + | − | + * | − | − | + | + | − | 517 | 97 | CB380179.1 (554) | Jaouannet et al. (2012) |

| Pectate lyase | 0, 3 | 219 | − | − | − | − | + | + * | + | − | − | − | − | 249 | 75 | CB279891.1 (499) | Doyle and Lambert (2002) |

| Peroxiredoxin | 0, 14 | 204 | + | − | + | + | + | + * | − | − | − | − | − | 516 | 96 | CB299476.1 (612) | Robertson et al. (2000) |

| Polygalacturonase | 0, 3 | 373 | + | + | + * | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 273 | 92 | BU095396.1 (566) | Jaubert et al. (2002a) |

| Venom allergen‐like proteins (Vap‐1) | 0, 3 | 245 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | 599 | 92 | BM416306.1 (1284) | Lozano‐Torres et al. (2012) |

*The numbers of contigs and singletons represent matches to cathepsins B, L, S, D and Z from the nematodes indicated in column 4; tblastx results are for cathepsin L of G. pallida.+ indicates presence of a similar sequence [expressed sequence tags (ESTs) or gene] of the respective nematode in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database.− indicates absence of a similar sequence (ESTs or gene) of the respective nematode in the NCBI database. Mi, Meloidogyne incognita; Mj, M. javanica; Mh, M. hapla; Gp, Globodera pallida; Gr, G. rostochiensis; Hg, Heterodera glycines; Hs, H. schachtii; Rs, Radopholus similis; Da, Ditylenchus africanus; As, Ascaris suum; Pv, Pratylenchus vulnus.

A notable feature was that many transcripts similar to those encoding effectors and thought to be required for giant cell or syncytium formation by root knot and cyst nematodes were not found in the P. zeae transcriptome. Examples of these include the secreted effector 7E12 (AF531166.1), for which over‐expression in tobacco accelerates giant cell formation induced by M. incognita (de Souza Junior et al., 2011), and CLE peptide and 16D10 CLE‐related proteins (e.g. DQ087264.1), known to influence transcriptional regulation processes that promote giant cell induction (Huang et al., 2006). Similarly, we did not find homologues of the C‐terminally Encoded Peptide (CEP) family of regulated peptides which contribute to the control of root development in vascular plants (Matsubayashi, 2011). A recent survey identified similar peptides in the M. hapla genome. These peptides have structural similarities to those present in plants, and have been suggested to play a role in the modification of root structures during nematode infection (Bobay et al., 2013). In a local blastx comparison of the P. zeae transcripts with CEPs of M. hapla (MhCEP1–12; Bobay et al., 2013), plant homologues of Medicago truncatula (MtCEP1–11; Bobay et al., 2013) and those in Arabidopsis thaliana (AtCEP1–5; Bobay et al., 2013), none of the transcripts were similar to any of the CEPs at an E‐value threshold of 1E‐03. In addition, we did not find any P. zeae transcript matching the taxonomically restricted MAP‐1 gene (e.g. AJ278663.1) of Meloidogyne species, which is potentially involved in the early stages of host recognition (Semblat et al., 2001). In the same way, we did not identify any transcript similar to three cyst nematode genes which encode effectors secreted via the oesophageal gland cells. These were the effectors Hg30C02 effector (JF896103) of H. glycines, the expression of which increases the susceptibility of Arabidopsis to infection by H. schachtii, Hs19C07 (AF490250.2), which interacts with the Arabidopsis auxin influx transporter LAX3 to facilitate syncytium development, and 10A06 (GQ373257.1) of H. schachtii: host expression of this gene induces morphological changes, targets spermidine synthase and possibly disrupts Arabidopsis defence signalling, resulting in increased susceptibility to infection (Hamamouch et al., 2012; Hewezi et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011).

Putative secretome of P . zeae

The set of proteins identified in PPN secretions which appear to play specific roles in host interactions are collectively referred to as the secretome. For sedentary endoparasites, such proteins have typically been isolated from gland cells, whereas, for the filarial nematode B. malayi, they have been identified from excretory–secretory products of microfilariae, adult males and females at the host–parasite interface. A tblastx comparison of the P. zeae transcriptome with the secretomes of H. glycines, M. incognita and B. malayi revealed 193 contigs and 1233 singletons with sequence similarity to genes of 61 secreted peptides (Table 4). These were divided into 10 groups based on function, including those involved in structural and cytoskeletal functions, energy metabolism, and protein digestion and fate (Table 4). There were also matches to genes of peptides secreted in response to stress, those suggested to be involved in the evasion of host immune responses and, in the case of the PPNs, proteins secreted to modify plant cell wall polysaccharides. Amongst the 20 secreted peptides common in the secretomes of M. incognita and B. malayi were structural proteins (e.g. actin, tropomyosin family protein and high‐mobility group proteins), ubiquitination proteins, peptidases (e.g. aminopeptidase and serine carboxypeptidase) and proteins of unknown functions e.g. transthyretrin‐like proteins. Transcripts with high percentage identity to those encoding six proteins identified in three independent studies of excretory–secretory products of B. malayi life stages were also identified. Four of these (glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, galectin and cystatin‐type proteinase inhibitor) were also identified by proteomic analysis of the secretome of M. incognita (Bellafiore et al., 2008). The other two were the macrophage migration inhibitory factor 1, also an encoded protein in C. elegans, and triose‐phosphate isomerase (Bennuru et al., 2009). Thirteen secreted products of M. incognita and H. glycines, whose genes share high homologies to transcripts of P. zeae, have so far not been identified in the excretory–secretory products of B. malayi; these included eight of the parasitism genes in Table 3, four structural proteins and an ATP synthase (atp‐2).

Table 4.

P ratylenchus zeae transcripts with putative homology to those of proteins/peptides of the secretomes of M eloidogyne incognita and H eterodera glycines and secretory–excretory products of B rugia malayi

| Secretome of nematode | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretome of sedentary endoparasites | Excretory–secretory products of B. malayi life stages | |||||

| Proteins | M. incognita * | H. glycines † | Host–parasite interface‡ | Microfilariae, female and males§ | Adult life stage¶ | Number of matching contigs (singletons) |

| Structural/cytoskeleton/nuclear | ||||||

| Actin | YES | — | — | — | YES | 13 (186) |

| Calmodulin | YES | — | — | — | YES | 9 (26) |

| Tropomyosin family protein | YES | — | — | — | YES | 6 (120) |

| High‐mobility group (HMG) protein | YES | — | — | — | YES | 10 (37) |

| Intermediate filament protein | — | — | YES | — | — | 3 (12) |

| Cuticle collagen | — | — | YES | — | — | 8 (46) |

| N‐Heparan sulfate | — | — | YES | — | — | 0 (0) |

| Troponin C‐like protein | YES | — | — | — | — | 2 (0) |

| Myosin regulatory light chain | YES | — | — | — | — | 7 (72) |

| Polygalacturonase | YES | — | — | — | — | 0 (1) |

| Cellulose‐binding protein | YES | YES | — | — | — | 1 (1) |

| Twitchin (unc‐22) | YES | — | YES | — | — | 2 (42) |

| Guanylyl cyclase | — | YES | — | — | — | 2 (47) |

| Chitinase | — | YES | — | — | — | 0 (8) |

| Histone H4 | — | ‐ | YES | — | — | 1 (14) |

| Msp‐1 | — | YES | — | YES | YES | 2 (13) |

| Energy metabolism | ||||||

| 6‐Phosphofructokinase | — | — | — | — | YES | 0 (2) |

| Enolase | YES | — | — | YES | YES | 1 (11) |

| Fructose‐bisphosphate aldolase 1 | — | — | — | YES | — | 0 (0) |

| Transaldolase | — | — | YES | — | — | 1 (5) |

| ATP synthase (atp‐2) | YES | — | ‐ | — | — | 17 (72) |

| Adenylate cyclase | — | — | YES | — | — | 2 (9) |

| Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | — | — | YES | — | — | 3 (6) |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | YES | — | YES | YES | YES | 1 (1) |

| Guanylate kinase | — | — | YES | — | — | 8 (11) |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase | — | — | — | YES | — | 1 (4) |

| Protein digestion, folding and fate/calcium binding | ||||||

| Aminopeptidase | — | — | YES | YES | — | 3 (20) |

| Calreticulin | YES | — | — | — | YES | 0 (6) |

| Serine carboxypeptidase | — | — | — | — | YES | 2 (10) |

| Ubiquitin (extension protein) | YES | YES | — | — | YES | 0 (0) |

| Ubiquitin‐like protein SMT3 | YES | — | — | — | YES | 2 (8) |

| Peptidyl‐prolyl cis–trans isomerase | YES | — | YES | — | YES | 3 (23) |

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase | — | — | YES | — | YES | 9 (72) |

| Cytochrome c type 1 protein | — | — | YES | — | — | 2 (0) |

| SKP‐1 | — | YES | — | — | — | 3 (22) |

| Putative trypsin inhibitor | — | — | — | YES | — | 0 (13) |

| Calsequestrin family protein | — | — | — | YES | YES | 1 (5) |

| Cyclophilin | YES | — | — | — | YES | 3 (28) |

| Protein disulfide isomerase | — | — | — | — | YES | 4 (10) |

| Cytosol stress response and antioxidants | ||||||

| 14‐3‐3b | YES | — | — | — | YES | 5 (24) |

| Hsp 70 | YES | — | — | — | YES | 3 (9) |

| Heat shock 90 | — | — | — | YES | ‐ | 5 (26) |

| Glutathione peroxidase | YES | — | YES | YES | YES | 4 (16) |

| Thioredoxin | — | — | YES | — | YES | 3 (14) |

| Superoxide dismutase | YES | — | YES | YES | YES | 2 (16) |

| Translationally controlled tumour protein | YES | — | — | — | YES | 2 (1) |

| Annexin | YES | YES | — | — | — | 1 (17) |

| Glutathione‐S‐transferase | YES | — | — | — | — | 3 (12) |

| Glutathione reductase | — | — | YES | — | — | 3 (0) |

| Glutathione synthetase | YES | — | — | — | — | 3 (6) |

| — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Lectins and glycosyltransferases | ||||||

| Galectin | YES | — | YES | YES | YES | 7 (33) |

| N‐Acetylglucosaminyltransferase | — | — | — | — | YES | 2 (9) |

| C‐type lectin | — | — | — | — | YES | 1 (0) |

| Protease inhibitors | ||||||

| Cystatin‐type cysteine proteinase inhibitor | YES | — | YES | YES | YES | 3 (1) |

| Lipid binding | ||||||

| Phosphatidylethanolamine‐binding protein | — | — | YES | — | YES | 1 (10) |

| Fatty acid retinol‐binding protein | YES | — | — | — | — | 2 (8) |

| Other proteins | ||||||

| TTLs | YES | — | YES | — | YES | 9 (36) |

| Venom allergen‐like proteins | YES | — | YES | — | ‐ | 0 (1) |

| Mucin‐like protein | — | — | — | — | YES | 1 (3) |

| Host cytokine homologues | ||||||

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor 1 (MIF‐1) | — | — | YES | YES | YES | 0(0) |

| Plant cell wall degradation enzymes | ||||||

| Pectate lyase | YES | YES | — | — | — | 0 (1) |

| Endoglucanase (and precursors) | YES | YES | — | — | — | 1 (27) |

In addition, 765 P. zeae transcripts matched 531 ESTs isolated from the single dorsal and/or the two subventral oesophageal gland cells in pre‐parasitic and parasitic stages of H. glycines (Gao et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2001). The characterization of these ESTs and those identified above is needed to determine whether they are indeed secreted by P. zeae.

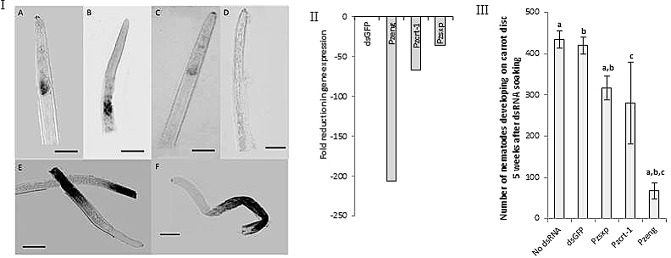

Functional characterization of P . zeae transcripts

Pratylenchus zeae transcripts putatively encoding five proteins were characterized using in situ hybridization and/or RNAi: these were putative transcripts for troponin C (with the C. elegans RNAi phenotype pat‐10) and calponin (unc‐87), both of which are essential for structural integrity and appropriate muscle contraction in nematodes, and three putative parasitism genes: β‐1,4‐endoglucanase (eng), calreticulin (crt‐1) and a transcript for the SXP‐RAL2 protein (sxp). Primers were designed using transcripts with the highest percentage identity to the characterized genes, and were employed successfully to amplify P. zeae transcripts from the mRNA used for transcriptome sequencing, employing reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) as described in Methods S1 (see Supporting Information): the amplicons were designated Pzpat‐10 (282 bp), Pzunc‐87 (275 bp), Pzeng (400 bp), Pzcrt‐1 (354 bp) and Pzsxp (234 bp) (Methods S1). Sequences of the amplicons were determined by Sanger sequencing, and each was 100% similar to the contigs/singletons from which the primers were designed (Methods S1, Table S3a–e, see Supporting Information). tblastx search revealed that they were also identical to genes of many PPNs (Table S3a–e). Notably, matches to Pzeng included endoglucanases with GH5 activity of several bacteria, including species of Sorangium, Saccharophagus, Cellulophaga and Hymenobacter, suggesting the acquisition of such genes from bacteria via horizontal gene transfer (Table S3a).

The P. zeae amplicons were then cloned into a transcription vector, pDoubler: we designed this vector for the synthesis of RNA probes and double‐stranded RNA (dsRNA) for in vitro RNAi (Methods S1). Digoxigenin (DIG)‐labelled RNA antisense probes synthesized from DNA templates digested from pDoubler clones for Pzeng, Pzcrt‐1 and Pzsxp all hybridized to the pharyngeal region of P. zeae juvenile and adult stages, behind the median bulb, suggesting that they may be secreted via the pharyngeal glands (Fig. 8I). In contrast, for Pzpat‐10 and Pzunc‐87, intense non‐specific hybridization was observed in all stages of the nematodes, and hybridization was generally localized at the anterior end of the nematodes (Fig. 8I). There was no hybridization with the sense probes of any of the genes.

Figure 8.

Functional characterization of P zeng, P zcrt‐1, P zsxp, P zpat‐10 and P zunc‐87. (I) In situ hybridization of P zeng (A), P zcrt‐1 (B), P zsxp (C), sense probe of P zeng (D), P zpat‐10 (E) and P zunc‐87 (F). Scale bar represents 50 μm. (II) Fold reduction of gene expression of P zeng, P zcrt‐1 and P zsxp in nematodes 16 h after incubation with the corresponding double‐stranded RNA (dsRNA) compared with expression in nematodes soaked with double‐stranded green fluorescent protein (dsGFP). (III) Reduction in number of P ratylenchus zeae on carrot discs 5 weeks after soaking with dsPzeng, dsPzcrt‐1 and dsPzsxp. Note that bars with the same letters represent significantly different means (P < 0.05).

To further characterize the three putative parasitism genes using RNAi, dsRNAs corresponding to Pzeng, Pzcrt‐1, Pzsxp and 715 bp of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) were synthesized using the transcription vector pDoubler, which has two opposing T7 polymerase promoters on either side of a multiple cloning site, as described in Methods S1. For each gene, 2000 vermiform P. zeae were soaked in 2 μg/μL dsRNA (designated dsPzeng, dsPzcrt‐1, dsPzsxp and dsGFP), resuspended in M9 buffer with 0.05% gelatin, 3 mm spermidine trihydrochloride and 50 mm octopamine, and incubated for 16 h at 25 °C. Compared with nematodes soaked in medium without dsRNA and with dsGFP, both used as controls, no effect was observed on the behaviour and activity of P. zeae nematodes soaked in dsRNA of the endogenous genes for 16 h. However, when the transcript abundance of the endogenous target genes in 500 of these nematodes was assessed 16 h after incubation by quantitative PCR, and relative expression was determined using the ΔΔCt method with 18S rRNA expression as internal control, there was a reduction in expression of all three genes. Target gene expression levels were determined for control nematode treatments (either no dsRNA or treated with dsGFP) and dsRNA of target genes: this enabled the discrimination of the effects of the stress of feeding a non‐specific dsRNA from the effects of the down‐regulation of expression of the target genes. There was a 207‐fold reduction in transcript abundance for Pzeng, 67‐fold for Pzcrt‐1 and 36‐fold for Pz‐sxp compared with the expression in nematodes soaked with dsGFP (Fig. 8II).

To assess the possible effects of the down‐regulation of target genes by RNAi on nematode reproduction, 50 nematodes each from the in vitro RNAi soaking treatments were used to infect five replicates of carrot mini discs, and the number of nematodes was counted after 5 weeks, as described by Tan et al. (2013). After this period, the number of nematodes present on carrot discs not treated with dsRNA or with dsGFP increased about nine times, and there was no significant difference between the two treatments (P < 0.05; Fig. 8III). For the nematodes treated with dsRNA to target genes, the numbers extracted after 5 weeks for those soaked in dsPzcrt‐1 increased seven times over the primary inoculum, but this did not differ significantly from the controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 8III). In contrast, there was a significant reduction in the reproduction of nematodes soaked with dsPzsxp and dsPzeng: after 5 weeks of culture, the number of nematodes soaked in dsRNA of these targets was substantially less, with an 84% reduction in numbers for dsPzeng compared with the control (no dsRNA) (Fig. 8III). These results mirror previous work, in which we showed that similar treatment of P. zeae with dsRNA of Pzpat10 and Pzunc87 substantially reduced transcript levels and significantly reduced the reproduction of P. zeae in carrot discs (Tan et al., 2013).

Discussion

This study provides the first sequence data on the transcriptome of the RLN P. zeae, a significant pest of crop plants, such as sugarcane and sorghum. Analysis of the data focused on transcripts likely to encode structural proteins and those involved in locomotion, sensitivity to external stimuli and host parasitism. About 60% of the total reads were assembled with SoftGenetics NextGENe V2.16 software into 10 163 contigs, leaving 139 104 singletons. This relatively large number of singletons could have been a result of the stringent base overlapping parameters used for contig assembly, which could also lead to singletons matching the same blast hits as contigs (and, in some cases, more singletons having higher blast hit percentage identities to hits than contigs). However, assembly of the reads with both CLC Genomics Workbench and Newbler also generated singletons, although less than in the NextGEne assembly. blastx of the resulting transcripts with C. elegans proteins showed that some singletons and contigs from each assembly were identical to the same C. elegans proteins. This suggests that the read coverage may not be sufficiently large for a complete assembly. Nevertheless, the use of both contigs and singletons of appropriate length in annotation, as performed here, provides useful new information, because some singletons not only matched similar characterized genes, but had sufficiently high percentage identities to warrant further characterization, as demonstrated by the strong reduction in nematode reproduction on carrot discs after soaking P. zeae with dsRNA of Pzcrt‐1 and Pzsxp. About 65% of contigs and 28% of singletons of the NextGEne assembly were similar to sequences of different nematodes (FLNs, APNs and PPNs). The transcripts matching genes common to all of these nematode species mainly encoded structural proteins or were involved in general metabolic and biological processes.

For RLNs, such as P. zeae, all juvenile stages (except J1s) and adults can move to and feed from a range of cells at the epidermis and within roots. In contrast, sedentary endoparasitic nematodes enter and migrate in host roots, and identify one or more specific host cells at which they control cell differentiation to develop permanent feeding sites (different forms of giant cells or syncytia; Jones, 1981; Jones and Goto, 2011), after which the nematodes become sedentary. As all feeding stages of P. zeae are motile and active, it is not surprising that most genes/transcripts are likely to be expressed throughout the infective stages of their life cycle. One such group of genes are those needed for different forms of movement, and P. zeae transcripts similar to 84 C. elegans genes were identified in the transcriptome with uncoordinated RNAi phenotypes (e.g. unc‐87), slo‐1 and sdn‐1 required for directional movement, and two neuropeptides (flp‐1 and flp‐7) that regulate sinusoidal movement and locomotory waveforms (Nelson et al., 1998; Reinitz et al., 2000). The importance of the correct functioning of two such genes (pat‐10 and unc‐87) has been demonstrated clearly in RNAi soaking experiments for three Pratylenchus species, including P. zeae, in which these two genes were down‐regulated after soaking in dsRNA and, subsequently, there was a significant reduction in reproduction (Soumi et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2013).

One interesting aspect of this study was the identification of many P. zeae transcripts with similarity to the genes involved in mechanosensory, chemosensory and thermosensory activities employed by C. elegans in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. There is no information available on whether P. zeae employs similar genes and mechanisms to sense and respond to chemicals in the rhizosphere, or to mechanical pressures in the soil environment, or to temperature changes, or what mechanisms it uses to evade or defend itself against plant immune responses, as such genes have been little studied in PPNs. Similarly, the free‐living C. elegans can be infected by pathogenic viruses and bacteria. Again, little is known about the interaction of PPNs and potential pathogens, although the Soybean cyst nematode midway virus has been found recently in the transcriptome of H. glycines (Bekal et al. 2011). The identification of transcripts similar to the C. elegans genes nlp‐29, bre‐3, bre‐4 and bre‐5 in the P. zeae transcriptome is therefore interesting and warrants further investigation—in C. elegans, their roles are to protect the nematode from biotic stresses.

This study adds to the increasing molecular information available for RLNs and highlights the similarities and differences in gene content between migratory and sedentary endoparasites (Jones, 1981; Jones and Fosu‐Nyarko, 2014; Jones and Northcote, 1972). Our analysis shows that P. zeae has 19 putative parasitism genes similar to those of P. coffeae and P. thornei (Haegeman et al., 2011; Nicol et al., 2012). However, transcripts of seven effectors widely reported to be important in sedentary nematode–host interactions and identified in the P. zeae transcriptome were not reported as expressed in the transcriptomes of P. coffeae and P. thornei (Haegeman et al., 2011; Nicol et al., 2012). These include transcripts for superoxide dismutase (required for stress response and protection), two proteases (aminopeptidase and serine protease) and SKP‐1, which has been identified in secretions of M. incognita and H. glycines, and is thought to be involved in ubiquitination (Bellafiore et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2003). Interestingly, our data, and similar data from P. coffeae and P. thornei, highlight, at the molecular level, differences in the lifestyles between migratory and sedentary endoparasitic nematodes. It further confirms that some genes present in sedentary endoparasitic nematodes, thought to be essential for host interactions, have not been identified so far in migratory RLNs. The genes apparently missing include secreted effectors involved in giant cell or syncytium formation, identified in sedentary endoparasitic nematodes, such as 7E12 (de Souza Junior et al., 2011), CEPs (Bobay et al., 2013), CLE peptide and 16D10 CLE (Huang et al., 2006), and MAP‐1, required for host recognition by root knot nematodes (Semblat et al., 2001), and effectors 10A06, Hs19CO7 and 30C02 of cyst nematodes (Hamamouch et al., 2012; Hewezi et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011). In the transcriptome analyses of P. thornei and P. coffeae (Haegeman et al., 2011; Nicol et al., 2012), transcripts were reported with very low percentage identity to the chorismate mutase encoded by sedentary nematodes, but no such match was found in the P. zeae transcriptome. It is not clear whether Pratylenchus spp. require this gene for host interactions, but, based on the characterized functions of chorismate mutases of fungi, plants and sedentary endoparasitic nematodes, it seems probable that a functional chorismate mutase is not present in RLN genomes.

Despite different lifestyles, there is nevertheless a common set of proteins or effectors in PPNs which enable them to invade root tissues and evade or suppress host immune responses. From this analysis, P. zeae also expresses transcripts that may encode 25 such effectors previously identified in sedentary PPNs and in other RLNs. These are required for common parasitic processes, including cell wall modification (pectate lyases and endoglucanases) required for migration in plant tissues. There is also a similarly large number of transcripts putatively encoding proteases, and gene products required to combat stresses, such as glutathione S‐transferase, superoxide dismutase and reducing agents, such as peroxiredoxin and thioredoxin, which may act against reactive oxygen species generated by the host, in addition to involvement in nematode metabolism. No proteomic studies have been published so far on the analysis of proteins secreted by Pratylenchus spp. However, we have identified a number of transcripts similar to those that encode proteins secreted by B. malayi, M. incognita and H. glycines, which suggests that parasitic nematodes may have similar genes, but the functions of these need to be determined for each nematode, because they may have evolved divergent roles that reflect different evolutionary pressures or lifestyles.

Although the molecular basis of host–pathogen interactions of RLNs has been less studied than that for sedentary PPNs, new sequencing technologies now make it possible to sequence whole transcriptomes or genomes of other PPNs, such as economically important Pratylenchus species. Here, we provide new data on the preliminary characterization of many expressed transcripts of P. zeae, including many potentially involved in nematode development, migration and feeding from cells of host tissues, and some which appear to be involved in protecting the nematode in soil and counteracting host defences in plant tissues. In this study, we have also examined the spatial expression of transcripts encoding putative homologues of five proteins required for movement or nematode parasitism by in situ hybridization. This analysis demonstrated that transcripts thought to encode a β‐1,4‐endoglucanase gene (Pzeng) and calreticulin (Pzcrt‐1), and a putative transcript of a SPRY‐containing protein (Pzsxp), are localized to P. zeae pharyngeal gland cells, which suggest that they may be secreted. Significantly, knockdown of Pzeng and Pzsxp by RNAi significantly reduced the multiplication of P. zeae in carrot discs. Although most of the genes identified require functional characterization, the data generated here have enabled the identification of potential targets for the development of new control strategies (Fosu‐Nyarko and Jones, 2015; Jones and Fosu‐Nyarko, 2014; Soumi et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2013). In addition, the characterization of transcripts with unknown function provides a further challenge: functional characterization is now required to generate a more complete picture to complement future sequencing and assembly of the genomes of Pratylenchus species.

Experimental procedures

Nematodes and RNA extraction

Vermiform juveniles and adults of P. zeae were harvested from the roots of infected sugarcane using a mist apparatus (Tan et al., 2013). Nematodes which migrated through the coffee filter were collected via tubing in a disposable syringe. Active nematodes were removed from the syringe at 4‐h intervals, and pelleted by gentle centrifugation. The nematodes were then resuspended in sterile water and washed by centrifugation and resuspension a further five times. The nematodes were then surface‐sterilized and inoculated onto surface‐sterilized carrot pieces maintained in vitro (Tan et al., 2013). Nematode surface sterilization involved suspending nematodes in 1% chlorhexidine gluconate (hibitane) for 20 min, followed by 1% streptomycin sulfate for 5 min; they were then washed five times with sterile water. Washing involved suspending nematodes in sterile water and centrifugation at 1000 g for 3 min: resuspension was by gentle inversion of the tubes three to five times, repeated five times. The nematodes were then examined by light microscopy to check for viability and any signs of microbial contamination before use. To further minimize any possible contamination before RNA extraction for transcriptome sequencing, mixed juvenile and adult stages of P. zeae were extracted from sterile carrot pieces and surface‐sterilized again. Nematode inocula added to carrot mini disc cultures and for RNAi feeding experiments were obtained from axenic stock cultures without further sterilization after extraction and washing with sterile distilled water.

Total RNA was extracted from freshly collected active nematodes using Trizol (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and RNA was cleaned with an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen Pty Ltd, Victoria, Australia). The quality and quantity of RNA were assessed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Mississauga, ON, Canada): RNA with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) greater than 7, with absorbance ratios of 260:280 at 2.1 and 260:230 at 2.0, was used for cDNA synthesis.

Sequencing and contig assembly

A cDNA library was prepared from 2.5 μg of total RNA using the Ovation RNA‐Seq system (NuGEN Technologies Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA), and the quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Half a picotitre plate was used to generate the 454 GS FLX dataset employing a Roche 454 GS FLX at the Institute of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Murdoch University, Perth, WA, Australia. Sequencing linkers were removed from all reads and de novo assembly was carried out using standard settings of the SoftGenetics NextGENe V2.16 software and the Condensation Tool (Manion et al., 2009). The average PHRED scores of the sequences were determined using CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5. The reads were also assembled with CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5 and GS De novo Assembler (Newbler) Version 2.5: the purpose was to assess whether the presence of singletons after the NextGEne assembly was a result of the algorithms of the software, or whether it related to read coverage. The set of parameters used for the CLC Genomics Workbench assembly was as follows: mismatch cost of 2, insertion cost of 2, deletion cost of 2, length fraction of 0.4 and similarity fraction of 0.9. The Newbler assembly was performed with the following settings: a seed step of 12, seed length of 16, seed count of 1, minimum overlap length of 40%, minimum overlap identity of 90% and alignment identity and difference scores of 2 and –3, respectively.

Calculation of AI for transcripts

The detection of possible contaminating sequences in the transcriptome was assessed using AI analysis. AI was calculated for P. zeae transcripts with a blast hit to at least one metazoan or a non‐metazoan sequence in the NCBI non‐redundant nr/nt database using the following formula described by Gladyshev et al. (2008) and Eves‐van den Akker et al. (2014): AI = log(best metazoan E‐value + 1E‐200) − log(best non‐metazoan E‐value + 1E‐200). When no metazoan or non‐metazoan significant blast hit was found, an E‐value of unity was automatically assigned and, consequently, no AI value was obtained for transcripts in which there was no significant hit in the non‐redundant database. Transcripts with AI > 0, indicating a better hit to a non‐metazoan species than to a metazoan species, were considered as possible contaminants and excluded from further analysis.

Functional classification

The transcripts were characterized using tblastx with a cut‐off expected (E)‐value of 1E‐5 (Camacho et al., 2009; Hunter et al., 2009). The GO functional classification scheme was used to assign the transcripts into three GO functional groups: molecular function, biological processes and cellular components (Ashburner et al., 2000). The molecular function category described the putative functions of transcripts based on their involvement in fundamental and cellular activities, whereas the biological process category included transcripts encoding gene products involved in molecular events and pathways. The cellular component category grouped the transcripts that encoded structural proteins of cells or their extracellular environment. As an alternative approach to annotation and to determine their biochemical functions, the transcripts were assigned to metabolic pathways using KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/KEGG/) enzyme commission (EC) and orthology (KO) pathways (Kanehisa et al., 2010). tblastx results against KEGG databases (nucleotide and amino acid) were parsed to obtain KEGG identifiers and EC numbers, which were matched to specific metabolic pathways. The results were then compiled, and percentages of the transcripts in each functional group (or pathway) were determined.

Comparative analysis with nematode sequences