Summary

The analysis of the interaction between Arabidopsis thaliana and adapted (PcBMM) and nonadapted (Pc2127) isolates of the necrotrophic fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina has contributed to the identification of molecular mechanisms controlling plant resistance to necrotrophs. To characterize the pathogenicity bases of the virulence of necrotrophic fungi in Arabidopsis, we developed P. cucumerina functional genomics tools using Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation. We generated PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP transformants constitutively expressing the green fluorescence protein (GFP), and a collection of random T‐DNA insertional PcBMM transformants. Confocal microscopy analyses of the initial stages of PcBMM‐GFP infection revealed that this pathogen, like other necrotrophic fungi, does not form an appressorium or penetrate into plant cells, but causes successive degradation of leaf cell layers. By comparing the colonization of Arabidopsis wild‐type plants and hypersusceptible (agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3) and resistant (irx1‐6) mutants by PcBMM‐GFP or Pc2127‐GFP, we found that the plant immune response was already mounted at 12–18 h post‐inoculation, and that Arabidopsis resistance to these fungi correlated with the time course of spore germination and hyphal growth on the leaf surface. The virulence of a subset of the PcBMM T‐DNA insertional transformants was determined in Arabidopsis wild‐type plants and agb1‐1 mutant, and several transformants were identified that showed altered virulence in these genotypes in comparison with that of untransformed PcBMM. The T‐DNA flanking regions in these fungal mutants were successfully sequenced, further supporting the utility of these functional genomics tools in the molecular characterization of the pathogenicity of necrotrophic fungi.

Introduction

Necrotrophic fungi, such as Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria brassicicola and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, cause severe diseases in a wide range of crops, as well as in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Bolton et al., 2006; Cramer and Lawrence, 2004; Perchepied et al., 2010; Williamson et al., 2007). These fungal pathogens usually induce host cell death, and can proliferate and develop on dead and decaying tissue (reviewed in van Kan, 2006). During tissue colonization, some necrotrophic fungi develop differentiated structures, called appressoria, that physically breach the host cuticle and cell wall barriers by exerting high turgor pressure (Howard and Valent, 1996) and secreting cell wall‐degrading enzymes (CWDEs; Ospina‐Giraldo et al., 2003; Reignault et al., 2008). However, many necrotrophic fungi do not form appressoria and penetrate the leaf surface directly by producing CWDEs (Chen et al., 2004; Jenczmionka et al., 2003; Mendgen et al., 1996; Mendoza‐Mendoza et al., 2003; Di Pietro et al., 2001). Necrotrophic fungi may also produce host‐specific toxins or race‐specific avirulence proteins that interfere with the host resistance response to favour fungal colonization (Friesen et al., 2008; Lawrence et al., 2008).

The filamentous fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina (Lindf.) W. Gams, anamorph Plectosporium tabacinum (van Beyma) M.E. Palm, W. Gams, et Nirenberg (Palm et al., 1995), is a ubiquitous soil‐borne pathogen. Formerly known as Fusarium tabacinum (Gams and Gerlagh, 1968), and later as Microdochium tabacinum (von Arx, 1984), P. cucumerina is a common fungus in the rhizosphere and decaying tissues of a diverse range of plants. It has been widely reported as the causal agent of sudden death and blight in crops, such as cucurbits (Abad et al., 2000; Jimenez and Zitter, 2005; Mullen and Sikora, 2003; Sato et al., 2005; Vitale et al., 2007) and legumes (Chen et al., 1999; Dillard et al., 2005; Youssef et al., 2001), becoming an emergent pathogen in recent decades (Jimenez and Zitter 2005). Plectosphaerella cucumerina is also a natural pathogen of several weeds, including A. thaliana and Hydrilla verticillata (Berrocal‐Lobo et al., 2002; Smither‐Kopperl et al., 1999; Ton and Mauch‐Mani, 2004). The symptoms observed on infected plants include white‐ to cream‐coloured lesions on both the stems and the underside of the leaves coinciding with the leaf veins (Strickland et al., 2007). As the disease progresses, the infected stems become very brittle, often leading to breakage (Berrocal‐Lobo et al., 2002). Of note, this fungus also infects animals, such as the potato cyst nematode (Atkins et al., 2003; Jacobs et al., 2003).

The interaction between Arabidopsis and P. cucumerina is a well‐established pathosystem for the study of plant basal and nonhost resistance to necrotrophic fungi. Nonadapted P. cucumerina isolates (e.g. Pc2127 and Pc1187), which are unable to colonize Arabidopsis plants, as well as an adapted isolate (PcBMM), which is virulent on all Arabidopsis ecotypes tested, have been characterized (Llorente et al., 2005; Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010; Ton and Mauch‐Mani, 2004). The resistance of Arabidopsis to the adapted PcBMM isolate is genetically complex and multigenic, similar to that described in the majority of the interactions between crops and necrotrophic fungi (Denby et al., 2004; Llorente et al., 2005; Maxwell et al., 2007; Micic et al., 2004; Rowe and Kliebenstein, 2008). The analysis of the Arabidopsis–P. cucumerina pathosystem has contributed to the identification of novel components of plant defence. Thus, it has been found that the biosynthesis of tryptophan (trp)‐derived metabolites (depleted in cyp79B2cyp79B3 and pen2 mutants) and their targeted delivery at pathogen contact sites are required for Arabidopsis basal resistance to both nonadapted and adapted isolates of P. cucumerina (Bednarek et al., 2009; Lipka et al., 2005; Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2006). By contrast, the agb1‐1 mutant, defective in the β or γ subunits of Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G‐protein, shows a compromised resistance to the adapted PcBMM isolate, whereas its susceptibility to nonadapted P. cucumerina isolates is enhanced slightly in comparison with that of wild‐type plants (Delgado‐Cerezo et al., 2012; Llorente et al., 2005; Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010).

The analysis of the Arabidopsis–P. cucumerina interaction has also contributed to the demonstration that Arabidopsis resistance to necrotrophs depends on the precise regulation of different signalling pathways, such as those mediated by hormones, as Arabidopsis mutants defective in ethylene (ET), jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA) and auxin signalling pathways are more susceptible than wild‐type plants to both P. cucumerina and B. cinerea fungi (Berrocal‐Lobo et al., 2002; Hernández‐Blanco et al., 2007; Llorente et al., 2008). Plant cell wall structure/composition is also a resistant determinant for necrotrophic fungal colonization success: the irregular xylem (irx) mutants impaired in secondary cell wall cellulose synthase (CESA) subunits [AtCESA4 (IRX5), AtCESA7 (IRX3) and AtCESA8 (IRX1/ERN1)] show an enhanced resistance to P. cucumerina and other necrotrophic and vascular pathogens (Ellis et al., 2002; Hernández‐Blanco et al., 2007).

Recently, several screenings have been performed to identify virulence factors in necrotrophic fungi, such as B. cinerea and S. sclerotiorum (Amselem et al., 2011; reviewed in Tudzynski and Kokkelink, 2009). However, our current knowledge of the molecular and genetic bases controlling the virulence of necrotrophic fungi is scarce compared with that of hemibiotrophic and biotrophic fungi (reviewed in Deller et al., 2011). In other fungal pathogens, such as Magnaporthe oryzae, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici, Leptosphaeria maculans, Cryptococcus neoformans and Colletotrichum higginsianum, random insertional mutagenesis by Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation (ATMT) has been established and successfully exploited for large‐scale forward genetic screening to identify pathogenicity and virulence genes (Betts et al., 2007; Blaise et al., 2007; Huser et al., 2009; Jeon et al., 2007; Michielse et al., 2009).

In this article, we present the characterization of the genomic structure of P. cucumerina, and describe the first application of ATMT technology to P. cucumerina functional genomics. Using ATMT, we generated fungal transformants constitutively expressing green fluorescence protein (GFP) (PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP), which were used to characterize, by spectral confocal microscopy, the initial colonization stages of P. cucumerina in Arabidopsis wild‐type plants and resistant (irx1‐6) and hypersusceptible (agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3) mutants. We also used ATMT for insertional mutagenesis of P. cucumerina, and the virulence of a subset of the mutants generated in Arabidopsis wild‐type plants and agb1‐1 mutant was screened. The Arabidopsis–P. cucumerina functional genomics tools presented here will contribute to the identification of novel pathogenicity genes from necrotrophic fungi.

Results

Structural genomics of P. cucumerina isolates

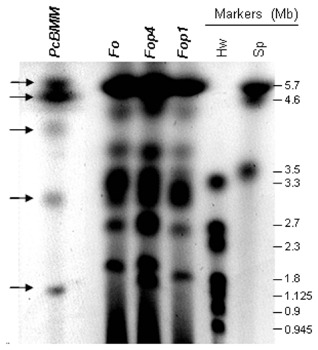

To gain some knowledge on the structural genomics of P. cucumerina fungi, we determined the karyotype of the adapted PcBMM isolate using different clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) gel electrophoresis conditions that allowed the separation of PcBMM chromosomes (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Three chromosomes of approximately 4, 3 and 1 Mb were clearly distinguishable in the PcBMM karyotype (Fig. 1). In addition, at least two 5‐Mb chromosomes and probably two 6‐Mb chromosomes, which could not be separated under the different CHEF conditions tested, were inferred from the ethidium bromide intensity of the corresponding bands (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Based on these data, the genome size of PcBMM could be estimated to be about 30 Mb = 6 + 6 + 5 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 1. The number of chromosomes and the genome size of PcBMM were lower than those of the three strains of F. oxysporum [FoAB82, and Fop1 and Fop4 (F. oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli); Alves‐Santos et al., 1999], which were included in the karyotype analyses for comparison. We also determined the karyotype of the nonadapted Pc1187 and Pc2127 strains, and found that they have an identical number of chromosomes of similar Mb, but lack the smallest 1‐Mb chromosome present in the PcBMM karyotype (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information). Moreover, the sizes of the two smallest Pc1187 and Pc2127 chromosomes differed from those of 4 Mb and 3 Mb observed in PcBMM CHEF analyses (Figs 1 and S1).

Figure 1.

Karyotype of the Plectosphaerella cucumerina BMM isolate. Chromosomes were resolved under small‐ and medium‐sized chromosome separation conditions by clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) and stained with ethidium bromide. From left to right: PcBMM, P. cucumerina isolate BMM; Fo, Fusarium oxysporum strain AB82; Fop1 and Fop4, F. oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli, strains 1 and 4, respectively; chromosome size markers (Mb) from Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Sp) and Hansenula wingei (Hw).

Early events in the colonization of Arabidopsis by PcBMM

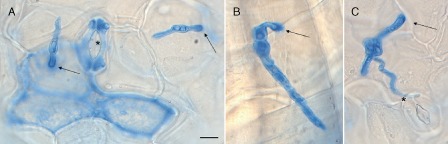

To characterize the initial colonization events of Arabidopsis plants by the adapted PcBMM isolate, leaves of wild‐type plants (Col‐0) were drop inoculated with a spore suspension (5 μL of 4 × 106 spores/mL) of the fungus. The progression of the infection was followed at different times post‐inoculation [6–48 h post‐inoculation (hpi)] on trypan blue (TB)‐stained leaves under bright field light microscopy, which allowed the detection of both fungal cell walls and dead plant cells (Fig. 2). These analyses revealed that the spore germination and hyphal growth of PcBMM occurred over the epidermal layer at earlier than 12 hpi (Fig. 2 and data not shown). The spores developed a first germ tube that remained attached to the leaf surface despite the intense washings of the TB staining protocol. Fungal penetration through the cell walls of epidermal stomata or trichomes was not observed (Fig. 2A–C). At the adhesion point of the fungal germ tube on the epidermal surface of the leaf, TB staining was very strong, but specialized penetration structures (e.g. appressoria) were not identified (Fig. 2A–C). TB staining was detected at the initial stages of infection in the plant cell in which adhesion of the fungal spore occurred, but also in some of the cells around this adhesion point (12–24 hpi), indicating that the fungus was able to impair the viability of these cells (Fig. 2A,B). At 24 hpi, the first mesophyll cell layer underlying the infection area accumulated the highest TB staining, indicating that plant cell death induced by PcBMM infection had also expanded to these layers under the epidermal adhesion cells despite the fact that these cells were not in direct contact with the fungus (Fig. S2, see Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Morphology of Plectosphaerella cucumerina at early stages of infection. Lactophenol trypan blue (TB) staining of PcBMM germinated spores at 12 h post‐inoculation (hpi) on Col‐0 leaves. Representative spores are shown in (A)–(C). Black arrows indicate the hyphal adhesion point to the epidermal surface of the plant, where a higher accumulation of the dye occurs. Stomata are indicated by stars (A,C) and trichomes by arrowheads (B). Scale bar, 10 μm.

ATMT of P. cucumerina

To characterize the initial events of Arabidopsis colonization by adapted and nonadapted P. cucumerina isolates, we generated PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP transformants constitutively expressing GFP, which were used for spectral confocal microscopy studies. To select the plasmid for P. cucumerina ATMT, we first determined the sensitivity of the fungal isolates to different concentrations of the selective antibiotics nourseothricin (NTC), hygromycin and geneticin. The first two compounds were chosen as selective antibiotics for ATMT, as PcBMM and Pc2127 growth was not detected on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates containing 100 μg/mL of any of these antibiotics (data not shown). Thus, the plasmids pDON and pDONG (G, GFP gene), both carrying the gene conferring NTC resistance (Krügel et al., 1993), were generated for P. cucumerina ATMT [Fig. S3 (see Supporting Information) and Experimental Procedures]. Transformation of PcBMM and Pc2127 spores with these plasmids was performed following the procedure developed for F. oxysporum ATMT (Mullins et al., 2001), and approximately 150 transformants/106 spores were obtained for both fungal isolates. Several monoconidial cultures showing an intense constitutive GFP fluorescence signal were found among the selected fungal transformants generated with pDONG, and their virulence was tested on Arabidopsis Col‐0 wild‐type plants and the hypersusceptible agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutants (Llorente et al., 2005; Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010). The PcBMM transformant DONG7.3 (named PcBMM‐GFP) was chosen for spectral confocal microscopy analyses, as it showed an intense GFP signal both in vitro and in planta, grew and sporulated in vitro like the PcBMM wild‐type, untransformed isolate and was as virulent as PcBMM in the Arabidopsis genotypes tested (data not shown). Similarly, the Pc2127 transformant DONG18.1 (named Pc2127‐GFP) was selected for studies of the colonization of Arabidopsis by a nonadapted isolate as it fulfilled the above‐mentioned criteria and, like Pc2127, colonized cyp79B2cyp79B3 plants, impaired in nonhost resistance, but not the Col‐0 and agb1‐1 genotypes (Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010).

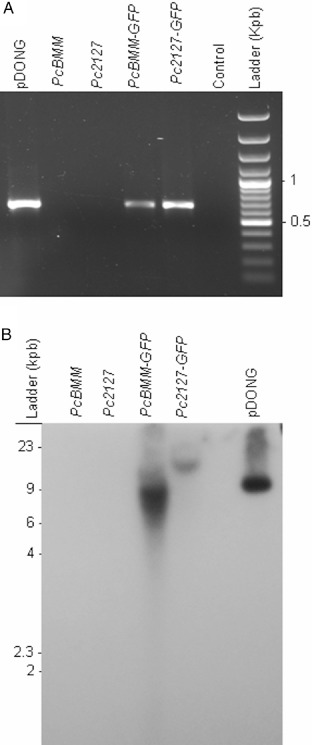

The two selected fungal transformants were mitotically stable and maintained their levels of GFP expression after repetitive subculture on nonselective medium. The insertion of T‐DNA in the Pc2127‐GFP and PcBMM‐GFP genomes was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the GFP encoding sequence with specific oligonucleotides that gave amplified DNA fragments (0.7 kbp) identical to those obtained from the PCR amplification of the pDONG plasmid used for transformation (Fig. 3A). Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from the Pc2127‐GFP, PcBMM‐GFP, PcBMM and Pc2127 isolates, and the pDONG plasmid, was performed using the NTC probe to detect the T‐DNA insertion, and it was found that the selected fungal transformants harboured just one T‐DNA insertion in their genomes (Fig. 3B). The DNA flanking sequences of the T‐DNA insertions in PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP were amplified by thermal asymmetric interlaced‐polymerase chain reaction (TAIL‐PCR). The sequences of the PcBMM‐GFP amplified products showed a low similarity with predicted protein or DNA sequences in the blast comparisons performed (Table S1, see Supporting Information), suggesting that either the T‐DNA insertion was in the noncoding region of the P. cucumerina genome or in a putative P. cucumerina gene with low sequence similarity with known fungal genes. Attempts to obtain the T‐DNA flanking region of Pc2127‐GFP failed, as we amplified pDON sequences in the right and left borders of T‐DNA, suggesting the presence of in‐tandem T‐DNA insertion, as has been reported previously in the screening of other T‐DNA mutants (Michielse et al., 2009).

Figure 3.

Characterization of PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP transformants. (A) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of green fluorescence protein (GFP) DNA from pDONG (positive control), PcBMM, Pc2127, PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP using the GFP‐A and GFP‐B oligonucleotides. Water was used for PCR negative control. Ladder DNA fragments (kbp) are shown. (B) Southern hybridization with NTC probe of genomic DNA from different isolates/transformants digested with XbaI. Ladder DNA size markers are shown.

Colonization of Arabidopsis leaves and roots by the adapted PcBMM‐GFP

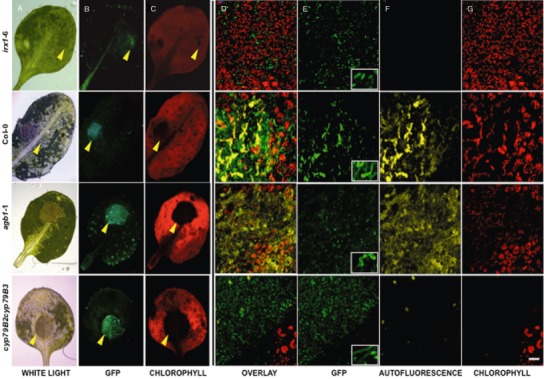

We monitored at different time points the colonization of distinct Arabidopsis genotypes by PcBMM‐GFP using a fluorescence stereomicroscope and a confocal microscope. Leaves from wild‐type plants (Col‐0), the hypersusceptible agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutants and the broad‐spectrum‐resistant irx1‐6 plants were drop inoculated with a spore suspension of PcBMM‐GFP (5 μL of 4 × 106 spores/mL) and the infection process was analysed from 12 to 72 hpi by following the GFP fluorescence signal. At 72 hpi, fluorescence of PcBMM‐GFP in the inoculated area was detected under a stereomicroscope (Fig. 4A–C). The intensity of the GFP fluorescence at the inoculation points correlated with a significant increase in chlorophyll degradation determined by the decay of the red autofluorescence of chlorophyll, which is an indicator of the maintenance of cell viability (Hörtensteiner and Kräutler, 2011; Prado et al., 2011; Fig. 4A–C). This decay was higher in the hypersusceptible agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutants than in the susceptible Col‐0 wild‐type plants, whereas it was almost undetectable in the resistant irx1‐6 mutant (Fig. 4A–C).

Figure 4.

Comparison of PcBMM‐GFP infection in drop‐infected leaves of Col‐0, agb1‐1, cyp79B2cyp79B3 and irx1‐6. (A)–(C) Fluorescence stereomicroscope images of Col‐0, agb1‐1, cyp79B2cyp79B3 and irx1‐6 infected leaves at 72 h post‐inoculation (hpi) with 5 μL of 4 × 106 spores/mL of PcBMM‐GFP: (A) white light; (B) blue light excitation (450–490 nm); (C) green light excitation (540–580 nm). Yellow arrows indicate the position of the spore suspension drop. (D)–(G) Confocal microscopy images of germinating spores in the indicated genotypes at 12 hpi with 5 μL of 4 × 106 spores/mL of PcBMM‐GFP. These overlay projections show merged (D) and separate (E–G) fluorescence channels. (E) Fluorescence (green) emitted by PcBMM‐GFP. The inset shows a zoom of representative germinated spores. (F) Fluorescence (yellow) emitted by the plant in response to the infection. (G) Fluorescence (red) emitted by the plant chlorophylls. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Given the soil‐borne nature of P. cucumerina, we performed root inoculation assays to test whether P. cucumerina was able to colonize Arabidopsis through the roots and to reach the above‐ground vegetative tissue. Roots of wild‐type plants (Col‐0) and the cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutant were inoculated with a spore suspension (107 spores/mL) of PcBMM‐GFP, and the intensity of the GFP fluorescence in the inoculated roots was followed at different days post‐inoculation (dpi) using a fluorescence stereomicroscope. We found that PcBMM‐GFP colonized the roots of both genotypes and, in particular, those of the hypersusceptible cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutant, which showed macroscopic disease symptoms in the above‐ground tissue at 10 dpi [Fig. S4 (see Supporting Information) and data not shown]. Fungal biomass was determined in the roots and rosettes of the inoculated plants at several dpi by quantitative PCR amplification of the NTC gene, and DNA from the fungal transformant was detected in both tissues of Col‐0 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 genotypes, indicating that the fungus was able to colonize both plant tissues (Fig. S4A). The fungal biomass and disease symptoms were greater in the cyp79B2cyp79B3 hypersusceptible mutant than in Col‐0 plants, which further supported the relevance of Trp‐derived metabolites in the basal resistance of roots to soil‐borne fungi (Fig. S4).

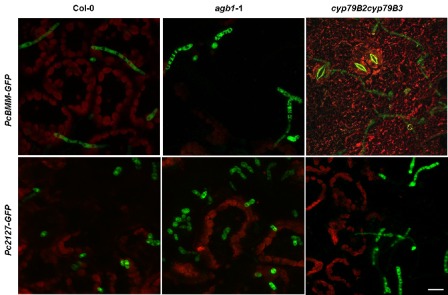

Comparative confocal studies of the colonization of different Arabidopsis genotypes by PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP

The initial stages of Arabidopsis colonization by PcBMM‐GFP were also studied by confocal microscopy. The fluorescence of the PcBMM‐GFP fungus and of plant chlorophyll from the inoculated Col‐0 plants and agb1‐1, cyp79B2cyp79B3 and irx1‐6 mutants was captured on stacks of sequential focal planes at different hpi, from the first epidermal layer, where the drop containing the spore inoculum (5 μL of 4 × 106 spores/mL) was placed, to the first mesophyll layer, which contains large chloroplast‐bearing cells (Fig. 4D–G). We found that, at 12 hpi, the progression of fungal growth was proportionally inverse to the plant cell integrity, measured as the red autofluorescence signal of chlorophyll (Fig. 4D–G). Confocal images at different time points after inoculation revealed a correlation between the time course of spore germination, hyphal growth, plant cell death and macroscopic disease symptoms (Fig. 4D–G and data not shown). Thus, PcBMM‐GFP spores germinated earlier and produced longer hyphae in agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutants than in wild‐type plants (Fig. 4E, inset). The agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 plants showed the most intense and evident signals of cell degradation, as revealed by decreased chlorophyll autofluorescence, an indicator of the loss of cell viability (Hörtensteiner and Kräutler, 2011; Prado et al., 2011; Fig. 4G). These data are in agreement with the macroscopic symptoms produced by PcBMM, which caused the decay of agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 plants in less than 7 days (Llorente et al., 2005, Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010). In contrast, the inoculated irx1‐6 resistant mutant exhibited more chlorophyll autofluorescence than Col‐0 plants and the PcBMM‐GFP germinated spores did not reach the length observed in Col‐0 plants (Fig. 4D–G). In the Col‐0 genotype, plant cell degradation and PcBMM‐GFP hyphal growth exhibited an intermediate phenotype between those observed in irx1‐6 and agb1‐1/cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutants (Fig. 4D–G). All of these data indicate that the time course of spore germination and hyphal growth correlates with the susceptibility of the Arabidopsis genotypes tested, and therefore that the susceptibility/resistance of Arabidopsis genotypes to PcBMM is established at early stages of infection (12–16 hpi).

Projections of stacks from confocal sections revealed that viable cells (containing intact autofluorescent chloroplasts) were not detected in the infected areas at 12 hpi (Fig. S5, see Supporting Information). These results were confirmed on orthogonal projections across the xz and yz planes at different z positions from the first epidermal layer, where the spores were placed, to the first mesophyll cell level, where integrity of plant cells was missing (Fig. S5). In the leaves inoculated with PcBMM‐GFP spores, an additional autofluorescence signal to that of chlorophyll was observed at 16–36 hpi (Fig. 4F and data not shown). Complementary experiments were carried out with the Col‐0, irx1‐6, agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 genotypes using different spore concentrations of PcBMM and PcBMM‐GFP to elucidate the nature of this signal, as well as to discard possible interferences with the fluorescence of GFP. Spectral separation of the emission on the confocal microscope allowed us to determine that this broad emission spectral pattern of the plant had a maximum intensity at 560 nm (yellow colour), which partially overlapped with the GFP fluorescence signal (green colour and a maximum emission at 515 nm; Fig. S6, see Supporting Information). This plant autofluorescence was detected in susceptible Col‐0 and hypersusceptible agb1‐1, to a lower extent in cyp79B2cyp79B3 plants, and was almost undetectable in the irx1‐6 mutant (Fig. 4D,F).

We next analysed by confocal microscopy the colonization process that occurred after inoculation of Arabidopsis plants with the nonadapted Pc2127‐GFP transformant. We drop inoculated with a spore suspension (5 μL of 4 × 106 spores/mL) leaves from the wild‐type plants (Col‐0), which are not colonized by the Pc2127 isolate, the agb1‐1 mutant, which shows a weak susceptibility to this fungus, and the cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutant, which is fully susceptible to Pc2127 (Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010). The infection process was examined between 10 and 72 hpi by following the GFP fluorescence of the Pc2127‐GFP fungus, and this process was compared with that caused by PcBMM‐GFP (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Germination rates of Pc2127‐GFP spores on the leaf surface of wild‐type plants and the mutants tested were very similar and occurred between 10 and 12 hpi (data not shown), as has been reported previously (Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010). At 24 hpi, the germinated Pc2127‐GFP spores had longer hyphae on cyp79B2cyp79B3 plants than on Col‐0 and agb1‐1 plants (Fig. 5). By contrast, hyphal growth was observed at 24 hpi on the leaf surface of Col‐0 plants inoculated with the adapted PcBMM‐GFP, and also in the hypersusceptible cyp79B2cyp79B3 and agb1‐1 mutants, which supported a faster growth of the hyphae than that observed in Col‐0 plants (Fig. 5). These data further indicate that the virulence of the PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP transformants did not differ from that of the wild‐type isolates (Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010),

Figure 5.

Comparison of PcBMM‐GFP and Pc2127‐GFP infection in drop‐infected leaves of Arabidopsis plants. Confocal microscopy overlay projections of Pc2127‐GFP and PcBMM‐GFP spores on leaves of wild‐type plants (Col‐0) and agb1‐1 and cyp70B2cyp79B3 mutants at 24 h post‐inoculation (hpi). Fluorescence emitted by P. cucumerina GFP (green) and by chlorophylls (red) is shown. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Plectosphaerella cucumerina functional genomics platform

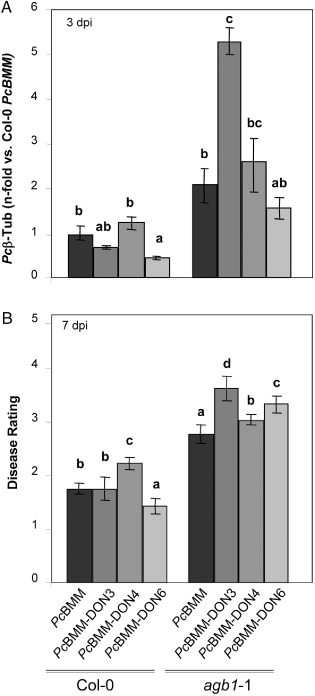

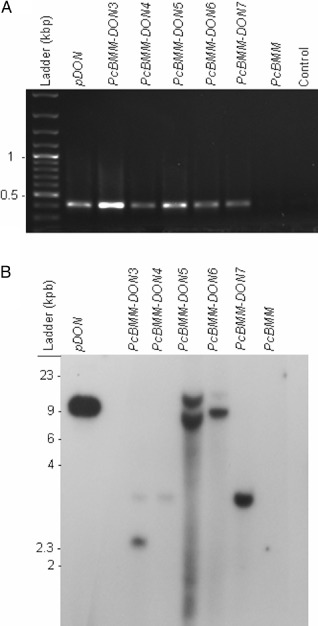

To determine whether ATMT may be a valuable method for the identification of P. cucumerina pathogenicity genes, we used the pDON vector carrying the NTC resistance gene to perform T‐DNA insertional mutagenesis in PcBMM. A first set of 300 stable NTC‐resistant transformants was obtained (average of 150 transformants/106 spores), and monoconidial cultures from 70 transformants were generated to test their virulence. Wild‐type (Col‐0) and agb1‐1 plants were sprayed with a spore suspension (4 × 106 spores/mL) of the different transformants, the virulent PcBMM isolate or water (mock inoculation), and infection progression was examined at different dpi by macroscopic evaluation of the disease rating (DR) and determination of fungal biomass using quantitative PCR (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Among the transformants tested, PcBMM‐DON3, PcBMM‐DON4 and PcBMM‐DON6 showed altered virulence in Col‐0 and/or agb1‐1 genotypes in comparison with that of the untransformed PcBMM isolate (Fig. 6): (i) PcBMM‐DON3 was more virulent than PcBMM in agb1‐1 plants at different dpi, whereas, in Col‐0 plants, it was less virulent than PcBMM at the initial stage of infection (3 dpi); (ii) PcBMM‐DON4 was slightly more virulent than PcBMM in Col‐0 and agb1‐1, in particular at later time points (7 dpi); and (iii) PcBMM‐DON6 was, by contrast, less virulent than PcBMM in Col‐0 and agb1‐1 plants at 3 dpi, but, at 7 dpi, its virulence in agb1‐1 plants was higher than that of the untransformed isolate. The presence of a T‐DNA insertion in PcBMM‐DON3, PcBMM‐DON4 andPcBMM‐DON6, as well as in additional transformants (e.g. PcBMM‐DON5 and PcBMM‐DON7), was confirmed by PCR amplification of the NTC sequence, which gave DNA fragments (0.4 kbp) of similar size to those obtained using the pDON plasmid as template (Fig. 7A). Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from these transformants using the NTC probe revealed that, in the selected transformants, there were either one (e.g. PcBMM‐DON4, PcBMM‐DON6 and PcBMM‐DON7) or two (e.g. PcBMM‐DON3 and PcBMM‐DON5) T‐DNA insertions (Fig. 7B). The T‐DNA flanking regions in these transformants were amplified by TAIL‐PCR, and the sequences of the amplified PcBMM‐DON3 and PcBMM‐DON4 products were found to show a high similarity with predicted fungal proteins or DNA sequences, whereas the amplified sequences in the rest of the transformants did not show significant similarities with known proteins/genes, suggesting that either the T‐DNA insertions were in noncoding regions of the P. cucumerina genome or in P. cucumerina genes with low sequence similarity with known fungal genes (Table S1). The imperfect repeat sequences in which the T‐DNA insertions took place were analysed (Fig. S7, see Supporting Information) and, remarkably, we found that they showed some similarities with those previously reported in ATMT of other fungi (Choi et al., 2007; de Groot et al., 1998; Li et al., 2007; Michielse et al., 2009; Mullins et al., 2001).

Figure 6.

PcBMM‐DON mutants exhibiting different phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana infections. (A) Quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) quantification of Plectosphaerella cucumerina DNA (Pc β‐tubulin) at 3 days post‐inoculation (dpi) with PcBMM or PcBMM‐DON mutants. Values (± SDs) are represented as the average of the n‐fold fungal DNA levels relative to PcBMM‐infected wild‐type (Col‐0) plants. (B) Average disease rating (DR ± SD) of the indicated Arabidopsis genotypes at 7 dpi. DR varies between 0 (no symptoms) and 5 (dead plant). The letters indicate values statistically significantly different from those of PcBMM‐infected genotypes (anova, P ≤ 0.05, Bonferroni's test). The experiments were performed three times with similar results.

Figure 7.

Characterization of PcBMM‐DON transformants. (A) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of NTC gene in PcBMM‐DON transformants using OliC and Nat1U oligonucleotides. From left to right: DNA ladder; PCR products from pDON vector (positive control), PcBMM‐DON transformants, PcBMM wild‐type isolate; negative control (water). (B) Southern blot hybridization with the NTC probe of genomic DNA from the indicated isolates/tranformants digested with PstI. DNA size markers are shown.

Discussion

In this study, we have used ATMT to develop P. cucumerina functional genomics tools to characterize the initial events of the colonization of Arabidopsis plants by both adapted (PcBMM‐GFP) and nonadapted (Pc2127‐GFP) isolates of this necrotrophic fungus, and to identify novel pathogenicity fungal genes controlling this process. The results presented here demonstrate that PcBMM isolate colonizes the leaves of its natural host, A. thaliana, using virulence mechanisms that are similar to those described previously for other necrotrophic fungi, such as B. cinerea (Choquer et al., 2007; van Kan, 2006). TB staining of inoculated leaves revealed that the fungal germ tubes remained attached to the epidermal cells despite TB staining and subsequent washings, and also that primary hyphae grew through the outer surface of the epidermal cell layer (Fig. 2). The presence of infection‐specific structures, such as appressoria, which are required for the penetration of host cells by some fungal pathogens (De Jong et al., 1997), were not found in the plant cells where the adhesion of the spores occurred. Spore adhesion points similar to those observed here have been described during the colonization of some plant species by B. cinerea, and have been referred to by some authors as appressoria, despite the fact that they are unable to penetrate directly the plant cell wall (Williamson et al., 2007). This may also occur during P. cucumerina infection, but the presence of melanin and certain specific appressoria marker proteins in the P. cucumerina germ tubes should be determined to prove this hypothesis (Doss et al., 2003). TB staining and confocal studies of the fungal infection areas revealed that, after germ tube formation (12–24 hpi), the adapted PcBMM fungus was able to affect plant cell viability, as specific TB staining and significant reduction of chloroplast autofluorescence were observed in the plant cells at the adhesion points and in the surrounding cells (Figs 2 and 4), as has been described for other necrotrophic fungi (van Baarlen et al., 2007). These analyses demonstrated that, in the inoculated areas, reduction of chlorophyll autofluorescence was stronger in the susceptible agb1‐1 and cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutants than in Col‐0 wild‐type plants, whereas, in the inoculated resistant irx1‐6 plants, no diminution of chlorophyll autofluorescence was observed (Fig. 4). Interestingly, these features correlated with the severity of the macroscopic symptoms observed and the intensity of the GFP signal detected by the fluorescence stereomicroscope at the inoculation points (Fig. 4), indicating that the PcBMM‐GFP transformant could be a useful tool to perform in vivo time course studies of P. cucumerina infection in different Arabidopsis genotypes. Notably, we found that PcBMM‐GFP was able to colonize the roots of Arabidopsis Col‐0 wild‐type plants and the cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutant impaired in nonhost resistance (Sánchez‐Vallet et al., 2010), and that this colonization was accompanied by the systemic spread of the fungal infection to the above‐ground tissue, which could be quantified by quantitative PCR amplification of the NTC gene (Fig. S4). These results were consistent with the described soil‐borne nature of several P. cucumerina isolates. In summary, the results presented here indicate that PcBMM‐GFP could be a valuable tool to study the genetic basis of Arabidopsis resistance to necrotrophic and soil‐borne (root‐infecting) fungi.

In agb1‐1 and Col‐0 wild‐type plants inoculated with PcBMM‐GFP, and to a smaller extent in the cyp79B2cyp79B3 mutant, we detected an additional autofluorescence signal with a maximum peak at 550 nm (yellow colour), which was identified on lambda scans and imaged separately from the GFP and chlorophyll fluorescence signals (Figs S6 and 4). This autofluorescence was hardly observed on the irx1‐6 mutant, suggesting that it could be a susceptibility‐related plant response to infection. In different plant species, autofluorescence has been detected in the areas surrounding the site of fungal infection (e.g. B. cinerea; Grovrin and Levine, 2002; Ponce de Leon et al., 2007), and has been reported to be indicative of the accumulation of different compounds in infected tissues (Billinton and Knight, 2001; Frye and Innes, 1998).

Using CHEF analysis, we have determined the PcBMM karyotype, which differs from that of different F. oxysporum isolates (Fig. 1), and have estimated the PcBMM genome size to be around 30 Mb (Fig. 1). This size is slightly smaller than that of other ascomycete fungi, such as Verticillium dahliae (34 Mb), F. graminearum (36 Mb), B. cinerea (41 Mb), Magnaporthe grisea (41.7 Mb), F. verticilloides (42 Mb) and F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (61 Mb) (Klosterman et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2006). However, the value determined by CHEF analysis might be an underestimation of the fungal genome size, as has been shown previously for other fungi, such as Verticillium sp. and F. oxysporum (Klosterman et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2010). Notably, the 1‐Mb chromosome present in the adapted PcBMM was absent in the nonadapted Pc2127 and Pc1187 isolates (Fig. S1), suggesting that this chromosome could be a lineage‐specific (LS) genomic region, similar to those found in the vascular tomato pathogen F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici, which are enriched in genes related to pathogenicity. The transfer of LS chromosomes (LSCs) between otherwise genetically isolated strains has been suggested to explain the polyphyletic origin of host specificity and the emergence of new pathogenic lineages in F. oxysporum (Ma et al., 2010). To further prove that the 1‐Mb PcBMM chromosome is an LSC, further characterization of the virulence and karyotype of additional P. cucumerina strains will be needed.

In this study, we have set up the tools (ATMT) for high‐throughput forward genetic screening and identification of pathogenicity genes from the necrotrophic fungus PcBMM. Using co‐cultivation of Agrobacterium with germinating conidia of P. cucumerina, we have obtained an efficient genetic transformation (150 transformants/106 spores), which was similar or even higher than those reported previously for ATMT in other plant fungal pathogens (Huser et al., 2009; Maruthachalam et al., 2008; Talhinhas et al., 2008). We determined an average of 1.5 T‐DNA insertions per PcBMM transformant analysed, a value in line with those obtained in similar approaches performed with other fungi (Blaise et al., 2007; Duyvesteijn et al., 2005; Idnurm et al., 2004; Meng et al., 2007; Michielse et al., 2005). We have validated the ATMT tools developed by screening the virulence of a subset of T‐DNA insertional mutants, which led to the identification of three PcBMM transformants showing significant alterations in their virulence in Arabidopsis wild‐type plants (PcBMM‐DON6) or the hypersusceptible agb1‐1 mutant (PcBMM‐DON3, PcBMM‐DON4 and PcBMM‐DON6). The proportion of mutants with altered pathogenicity identified in this screening was similar to that described for large‐scale functional genomics screening in L. maculans, Colletotrichum species and M. grisea (Betts et al., 2007; Blaise et al., 2007; Huser et al., 2009; Jeong et al., 2007; Seong et al., 2007). TAIL‐PCR experiments carried out with the fungal transformants allowed us to identify the T‐DNA flanking sequences from the majority of the transformants, further confirming that ATMT of P. cucumerina has great potential for the large‐scale discovery of pathogenicity genes from necrotrophic fungi. Of note, the P. cucumerina functional genomics platform developed here will allow us to perform pathogenicity screenings in both Arabidopsis wild‐type plants and mutants impaired in different components of innate immunity, further providing a unique tool to study the impact of plant genetic determinants in the effectiveness of fungal pathogenicity factors.

Experimental Procedures

Biological materials and growth conditions

PcBMM isolate was kindly provided by Dr Brigitte Mauch‐Mani (University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland), and Pc2127 and Pc1187 were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ) Collection (Braunschweig, Germany). The F. oxysporum strain, AB82, and the F. oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli strains, 1 and 4, have been described previously (Alves‐Santos et al., 1999; Ramos et al., 2007). Spores from these fungi were obtained as reported by Hernández‐Blanco et al. (2007). For fungal DNA extraction, cultures were grown at 28 °C as described previously (Ramos et al., 2007). The Arabidopsis genotypes used in this study, agb1‐1 (Llorente et al., 2005), cyp79B2cyp79B3 (Zhao et al., 2002) and irx1‐6 (Hernández‐Blanco et al., 2007), were in the Col‐0 background. Plants were grown on sterilized soil as described by Hernández‐Blanco et al. (2007).

Arabidopsis inoculation with P. cucumerina

Inoculation of Arabidopsis leaves was performed by spraying 3‐week‐old soil‐grown plants with a spore suspension (4 × 106 spores/mL) of the fungus, as reported by Llorente et al. (2005). Disease progression was followed at different dpi and a DR in the range 0–5 was assigned to each individual plant (0, no symptoms; 5, dead plant; Llorente et al., 2005). At least 12 plants per genotype were inoculated and a minimum of three independent experiments was performed. Results are the means ± standard deviation (SD); statistically significant differences were determined by one‐way analysis of variance (anova) and Bonferroni post hoc test (Sánchez‐Rodríguez et al. 2009). For the root inoculation assays, 3‐week‐old soil‐grown Arabidopsis plants were carefully uprooted and the roots were washed with tap water and dipped in 1 mL of a 107 spore/mL suspension for 10 min. Then, plants were transferred to vermiculite substrate, and root and rosette samples were collected at different dpi. For the visualization of PcBMM‐GFP‐infected roots, 14‐day‐old plants growing on Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates were root inoculated with 200 μL of a 107 spore/mL suspension and fluorescence was captured at 3 dpi.

Fungal biomass quantification

For fungal DNA quantification, DNA from infected plants was extracted as described by Llorente et al. (2005). The QNat1‐F (5′‐CACTCTTGACGACACGGCTTAC‐3′) and QNat1‐R (5′‐GTGGTGAAGGACCCATCCAGT‐3′) oligonucleotides of the NTC gene employed for quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) were designed using PRIMER EXPRESS v2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA; http://www.appliedbiosystems.com). qRT‐PCR analyses were performed as reported previously, with 0.3 μm of each primer (Hernández‐Blanco et al., 2007), using the FS Universal SYBR GreenMasterRox (Roche, Basel, Switzerland; http://www.roche.com) and the amplification conditions described by Sánchez‐Rodríguez et al. (2009). The plant UBIQUITIN21 (At5G25760, UBQ21) gene was used to normalize and calculate the change in the cycle threshold (ΔCt) value. The relative expression ratio was determined from the expression 2–ΔΔCt (Rieu and Powers, 2009), using the relative quantification application of the sequence detector software (v1.4; Applied Biosystems; Rieu and Powers, 2009). The qRT‐PCR results are the means (± SD) of two technical replicates. Differences in expression ratios (ΔCt) among the samples were analysed by anova or Student's t‐test using statgraphics.

Pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis

Intact chromosomal DNA was prepared from protoplasts as reported by Alves‐Santos et al. (1999) and Boehm et al. (1994). Chromosomal DNA bands were separated in a contour‐CHEF system (CHEF mapper, Bio‐Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) under the electrophoretic conditions described previously (Alves‐Santos et al., 1999). Chromosomal preparations from Hansenula wingei and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Bio‐Rad Laboratories Inc.) were included as DNA size markers, and DNAs from other previously karyotyped fungi were used for comparison (Alves‐Santos et al., 1999; Ramos et al., 2007).

Vector construction and fungal transformation

The sensitivity of P. cucumerina isolates to the antiobiotics NTC (Jena Bioscience, GmbH, Jena, Germany), hygromicin (Roche) and geneticin G418 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was determined in both PDA and potato dextrose broth (PDB). For ATMT, the pDON vector was constructed by cloning the NTC cassette from the pNR2 plasmid (which includes the OliC promoter and Nat1 coding region) into the polylinker region of plasmid pDHt1 (Mullins et al., 2001) excised with PstI and XbaI endonucleases; the pDONG vector was constructed by cloning the GFP cassette [including the promoter of the glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD) gene from Aspergillus nidulans (pGPDA), the sGFP coding region and the TrpC terminator from plasmid pGPDAsGFP; Fernández‐Ábalos et al., 1998] into the polylinker region on plasmid pDON excised with the EcoRI and XbaI endonucleases (Fig. S2). The pDON and pDONG vectors were used to transform Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain AGL‐1 (Lazo et al., 1991) by electroporation, and these bacteria were utilized for the transformation of P. cucumerina spores, according to Mullins et al. (2001). Transformants were selected on regeneration medium containing 100 μg/mL of NTC, and then replicated to PDA medium containing the same antibiotic concentration. The stability of transformants was examined by culturing in PDA medium without NTC for 4–7 days, followed by an additional replica plating in PDA with and without NTC. Monoconidial cultures of the transformants were obtained by the selection of agar (15%)–water‐plated single spores under the stereomicroscope.

Molecular analysis of fungal transformants

The presence of T‐DNA insertions in the P. cucumerina transformants was checked by PCR of genomic DNA extracted from mycelium obtained as described by Alves‐Santos et al. (1999, 2002). The OliC‐F (5′‐GGAGGTTCGGCGTAGGGTTG‐3′) and Nat1‐R (5′‐GCCTGGACACCGCCCTG‐3′) oligonucleotides, which amplified a 0.4‐kbp fragment from NTC, and the GFP‐A (5′‐GCGGCGGTCACGAACTCC‐3′) and GFP‐B (5′‐GGGGTGGTGCCCATCCTG‐3′) oligonucleotides, which amplified a 0.7‐kbp fragment from the GFP gene, were used. PCR‐amplified fragments were purified from agarose gels using the Qiaex kit (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA, USA), and were sequenced with an ABI PRISM 377 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Capillary transfer of genomic DNA digested with different restriction enzymes (XbaI and PstI) to nylon hybridization membranes (Roche) was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). DNA probes were labelled with Digoxigenin‐11‐dUTP by the PCR method. DNA from pDONG was employed as template and hybridization was performed using a chemiluminescent detection procedure with CDP‐Star (Roche).

Sequencing of T‐DNA flanking regions

The sequencing of T‐DNA flanking regions was carried out by TAIL‐PCR following the conditions and primers indicated by Mullins et al. (2001). The tertiary TAIL‐PCR product(s) of each transformant was/were purified using a QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and sequenced. Taq Polymerase (Applied Biosystems) and PhusionHot Start II High‐Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Vantaa, Finland) were used in these PCRs. The sequences of TAIL‐PCR products were subjected to blastn and blastx (Altschul et al., 1990; Cummings et al., 2002) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/genom_table.cgi?organism=fungi)

Bright field, fluorescence and confocal microscopy

Lactophenol TB staining of inoculated plants was performed as reported by Sánchez‐Rodríguez et al. (2009) and bright field images were obtained on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a Leica DFC 300FX CCD colour camera under the Leica Application Suite 2.8.1 build 1554 acquisition software (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Fluorescence images were captured on a Leica MZ16F stereomicroscope equipped with a Leica DFC 490 CCD colour camera with the image acquisition and processing software Leica Application Suite 2.8.1 build 1554 (Leica Microsystems). Excitation ranges for blue (450–490 nm) and green (540–580 nm) light were used. Confocal images were acquired on a TCS SP2 AOBS spectral confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems) and on an LSM710 (Carl Zeiss). The autofluorescence emission profile of the leaves was determined on infected, non‐GFP‐tagged specimens by a lambda scan under the excitation lines 351, 364, 488 and 543 nm. Once spectrally differentiated autofluorescence profiles had been identified (one corresponding to a signal in the infection area and the other to chlorophyll), these were collected separately as follows: GFP fluorescence (green) was captured by excitation at 488 nm and emission in the range 490–520 nm; the autofluorescence signal in response to infection (yellow) was excited at 488 nm and the emission was recorded from 520 to 600 nm; and chlorophyll autofluorescence (red) was captured with an excitation of 543 nm and the emission was collected in the range 600–720 nm. Three‐dimensional xyz confocal stacks and orthogonal projections across selected xz and yz planes were analysed using Leica Confocal Software LCS Lite version 2.61 build 1538 (Leica Microsystems) and ZEN 2009 Light Edition software (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Karyotype of nonadapted Plectosphaerella cucumerina isolates.

Fig. S2 Arabidopsis mesophyll degradation on Plectosphaerella cucumerina infection.

Fig. S3 Plasmid vectors used for fungal transformation.

Fig. S4 Colonization of Arabidopsis roots by PcBMM‐GFP.

Fig. S5 Analysis of fungal infection progression by confocal microscopy.

Fig. S6 Lambda scanning of fluorescent signals of PcBMM‐GFP‐inoculated leaves.

Fig. S7 T‐DNA insertion flanking sequences from PcBMM‐DON and PcBMM‐DONG mutants.

Table S1 blast similarity of T‐DNA insertion sequences of PcBMM mutants

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs J. van Kan (Wageningen University, the Netherlands) and J. M. Fernández‐Ábalos [IMB, Universidad de Salamanca (USAL)‐Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cinetíficas (CSIC), Salamanca, USAL‐CSIC, Spain] for providing pNR2 and pGPDAsGFP plasmids, respectively, and to R. Martín Domínguez [Centro Hispano‐Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias (CIALE)‐Universidad de Salamanca (USAL), Salamanca, Spain] for technical assistance. We thank Drs J. M. Díaz‐Mínguez and A. P. Eslava (CIALE‐USAL, Spain) for providing CHEF mapper and FOP and FO chromosomal preparations, and Dr G. Sexton (Carl Zeiss, Barcelona, Spain) and M. T. Seisdedos [Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas (CIB)‐(CSIC), Madrid, Spain] for confocal technical supervision. Work in A. Molina's laboratory was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MICINN, grants BIO2009‐07161 and EUI2008‐03728/BALANCE). Dr B. Ramos was Ayudante from Universidad de Salamanca (Spain), and C. Sánchez‐Rodríguez and A. Sánchez‐Vallet were PhD Fellows from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación (MEC) and MICINN, respectively.

References

- Abad, P. , Pérez, A. , Marqués, M.C. , Vicente, M.J. , Bruton, B.D. and García‐Jiménez, J. (2000) Assessment of vegetative compatibility of Acremonium cucurbitacearum and Plectosphaerella cucumerina isolates from diseased melon plants. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 30, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F. , Gish, W. , Miller, W. , Myers, E.W. and Lipman, D.J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves‐Santos, F.M. , Benito, E.P. , Eslava, A.P. and Diaz‐Minguez, J.M. (1999) Genetic diversity of Fusarium oxysporum strains from common bean fields in Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 3335–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves‐Santos, F.M. , Cordeiro‐Rodrigues, L. , Sayagués, J.M. , Martín‐Domínguez, R. , García‐Benavides, P. , Crespo, M.C. , Díaz‐Mínguez, J.M. and Eslava, A.P. (2002) Pathogenicity and race characterization of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. phaseoli isolates from Spain and Greece. Plant Pathol. 51, 605–611. [Google Scholar]

- Amselem, J. , van Cuomo, C.A., Kan, J.A.L. , Viaud, M. , Benito, E.P. , Couloux, A. , de Coutinho, P.M., Vries, R.P. , Dyer, P.S. , Fillinger, S , Fournier, E. , Gout, L. , Hahn, M. , Kohn, L. , Lapalu, N. , Plummer, K.M. , Pradier, F.M. , Quévillon, E. , Sharon, A. , Simon, A. , ten Have, A. , Tudzynski, B. , Tudzynski, P. , Wincker, P. , Andrew, M. , Anhouard, V. , Beever, R.E. , Beffa, R. , Benoit, I. , Bouzid, O. , Brault, B. , Chen, Z. , Choquer, M. , Collémare, J. , Cotton, P. , Danchin, E.G. , Da Silva, C. , Gautier, A. , Giraud, C. , Giraud, T. , Gonzalez, C. , Grossetete, S. , Güldener, U. , Henrissat, B. , Howlett, B.J. , Kodira, C. , Kretschmer, M. , Lappartient, A. , Leroch, M. , Levis, C. , Mauceli, E. , Neuveéglise, C. , Oeser, B. , Pearson, M. , Poulain, J. , Poussereau, N. , Quesneville, H. , Rascle, C. , Chumacher, J. , Ségurens, B. , Sexton, A. , Silva, E. , Sirven, C. , Soanes, D.M. , Talbot, N.J. , Templeton, M. , Yandava, C. , Yarden, O. , Zeng, Q. , Rollins, J.A. , Lebrun, M.H. and Dickman, M. (2011) Genomic analysis of the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea . Plos Genet. 7, e1002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Arx, J.A. (1984) Notes on Monographella and Microdochium . Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 83, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, S.D. , Clark, I.M. , Sosnowska, D. , Hirsch, P.R. and Kerry, B.R. (2003) Detection and quantification of Plectosphaerella cucumerina, a potential biological control agent of potato cyst nematodes, by using conventional PCR, real‐time PCR, selective media, and baiting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 4788–4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Baarlen, P. , Woltering, E.J. , van Staats, M. and Kan, J.A.L. (2007) Histochemical and genetic analysis of host and non‐host interactions of Arabidopsis with three Botrytis species: an important role for cell death control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, P. , Pislewska‐Bednarek, M. , Svatos, A. , Schneider, B. , Doubsky, J. , Mansurova, M. , Humphry, M. , Consonni, C. , Panstruga, R. , Sánchez‐Vallet, A. , Molina, A. and Schulze‐Lefert, P. (2009) A glucosinolate metabolism pathway in living plant cells mediates broad‐spectrum antifungal defense. Science 323, 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal‐Lobo, M. , Molina, A. and Solano, R. (2002) Constitutive expression of ETHYLENE‐RESPONSE‐FACTOR1 in Arabidopsis confers resistance to several necrotrophic fungi. Plant J. 29, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts, M.F. , Tucker, S.L. , Galadima, N. , Meng, Y. , Patel, G. , Li, L. , Donofrio, N. , Floyd, A. , Nolin, S. , Brown, D. , Mandel, M.A. , Mitchell, T.K. , Xu, J.R. , Dean, R.A. , Farman, M.L. and Orbach, M.J. (2007) Development of a high throughput transformation system for insertional mutagenesis in Magnaporthe oryzae . Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 1035–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billinton, N. and Knight, A.W. (2001) Seeing the wood through the trees: a review of techniques for distinguishing green fluorescent protein from endogenous autofluorescence. Anal. Biochem. 291, 175–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise, F. , Remy, E. , Meyer, M. , Zhou, L. , Narcy, J.P. , Roux, J. , Balesdent, M.H. and Rouxel, T. (2007) A critical assessment of Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation as a tool for pathogenicity gene discovery in the phytopathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans . Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, E.W.A. , Ploetz, R.C. and Kistler, H.C. (1994) Statistical analysis of electrophoretic karyotype variation among vegetative compatibility groups of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 7, 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, M.D. , Thomma, B.P.H.J. and Nelson, B.D. (2006) Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: biology and molecular traits of a cosmopolitan pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. , Harel, A. , Gorovoits, R. , Yarden, O. and Dickman, M.B. (2004) MAPK regulation of sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is linked with pH and cAMP sensing. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 17, 404–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. , Gray, L.E. , Kurle, J.E. and Grau, C.R. (1999) Specific detection of Phialophora gregata and Plectosporium tabacinum in infected soybean plants using polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Ecol. 8, 871–877. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. , Park, J. , Jeon, J. , Chi, M.‐H. , Goh, J. , Yoo, S.‐Y. , Park, J. , Jung, K. , Kim, H. , Park, S.‐Y. , Rho, H.‐S. , Kim, S. , Kim, B.R. , Han, S.‐S. , Kang, S. and Lee, Y.‐H. (2007) Genome‐wide analysis of T‐DNA integration into the chromosomes of Magnaporthe oryzae . Mol. Microbiol. 66, 371–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquer, M. , Fournier, E. , Kunz, C. , Levis, C. , Pradier, J.M. , Simon, A. and Viaud, M. (2007) Botrytis cinerea virulence factors: new insights into a necrotrophic and polyphageous pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, R.A. and Lawrence, C.B. (2004) Identification of Alternaria brassicicola genes expressed in planta during pathogenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana . Fungal Genet. Biol. 41, 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, L. , Riley, L. , Black, L. , Souvorov, A. , Resenchuk, S. , Dondoshansky, I. and Tatusova, T. (2002) Genomic BLAST: custom‐defined virtual databases for complete and unfinished genomes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 216, 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, J.C. , McCormack, B.J. , Smirnoff, N. and Talbot, N.J. (1997) Glycerol generates turgor in rice blast. Nature, 389, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado‐Cerezo, M. , Sanchez‐Rodriguez, C. , Escudero, V. , Miedes, E. , Fernandez, P.V. , Jorda, L. , Hernández‐Blanco, C. , Sánchez‐Vallet, A. , Bednarek, P. , Schulze‐Lefert, P. , Somerville, S. , Estevez, J.M. , Persson, S. and Molina, A. (2012) Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G‐protein regulates cell wall defense and resistance to necrotrophic fungi. Mol. Plant 5, 98–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller, S. , Hammond‐Kosack, K.E. and Rudd, J.J. (2011) The complex interactions between host immunity and non‐biotrophic fungal pathogens of wheat leaves. Plant Physiol. 168, 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denby, K.J. , Kumar, P. and Kliebenstein, D.J. (2004) Identification of Botrytis cinerea susceptibility loci in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J. 38, 473–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro, A. , García‐Maceira, F.I. , Méglecz, E. and Roncero, M.I.G. (2001) A MAP kinase of the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum is essential for root penetration and pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1140–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, H.R. , Cobb, A.C. , Shah, D.A. and Straight, K.E. (2005) Identification and characterization of russet on snap beans caused by Plectosporium tabacinum . Plant Dis. 89, 700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss, R.P. , Deisenhofer, J. , Krug von Nidda, H.A. , Soeldner, A.H. and McGuire, R.P. (2003) Melanin in the extracellular matrix of germlings of Botrytis cinerea . Phytochemistry, 63, 687–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyvesteijn, R.G. , van Wijk, R. , Boer, Y. , Rep, M. , Cornelissen, B.J. and Haring, M.A. (2005) Frp1 is a Fusarium oxysporum F‐box protein required for pathogenicity on tomato. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 1051–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C. , Karafyllidis, I. , Wasternack, C. and Turner, J.G. (2002) The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 links cell wall signaling to jasmonate and ethylene responses. Plant Cell, 14, 1557–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández‐Ábalos, J.M. , Fox, H. , Pitt, C. , Wells, B. and Doonan, J.H. (1998) Plant‐adapted green fluorescent protein is a versatile vital reporter for gene expression, protein localization and mitosis in the filamentous fungus, Aspergillus nidulans . Mol. Microbiol. 27, 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, T.L. , Faris, J.D. , Solomon, P.S. and Oliver, R.P. (2008) Host‐specific toxins: effectors of necrotrophic pathogenicity. Cell. Microbiol. 10, 1421–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye, C.A. and Innes, R.W. (1998) An Arabidopsis mutant with enhanced resistance to powdery mildew. Plant Cell, 10, 947–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gams, W. and Gerlagh, M. (1968) Beiträge zur Systematik und Biologie von Plectosphaerella cucumeris und der zugehörende Konidienform. Persoonia, 5, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, M.J.A. , Bundock, P. , Hooykaas, P.J.J. and Beijersbergen, A.G.M. (1998) Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation of filamentous fungi. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 839–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grovrin, E.M. and Levine, A. (2002) Infection of Arabidopsis with a necrotrophic pathogen, Botrytis cinerea, elicits various defense responses but does not induce systemic acquired resistance (SAR). Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández‐Blanco, C. , Feng, D.X. , Hu, J. , Sánchez‐Vallet, A. , Deslandes, L. , Llorente, F. , Berrocal‐Lobo, M. , Keller, H. , Barlet, X. , Sanchez‐Rodriguez, C. , Anderson, L.K. , Somerville, S. , Marco, Y. and Molina, A. (2007) Impairment of cellulose synthases required for Arabidopsis secondary cell wall formation enhances disease resistance. Plant Cell, 19, 890–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörtensteiner, S. and Kräutler, B. (2011) Chlorophyll breakdown in higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1807, 977–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, R.J. and Valent, B. (1996) Breaking and entering: host penetration by the fungal rice blast pathogen Magnaporthe grisea . Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 491–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huser, A. , Takahara, H. , Schmalenbach, W. and O'Connell, R. (2009) Discovery of pathogenicity genes in the crucifer anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum higginsianum, using random insertional mutagenesis. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idnurm, A. , Reedy, J.L. , Nussbaum, J.C. and Heitman, J. (2004) Cryptococcus neoformans virulence gene discovery through insertional mutagenesis. Eukaryot. Cell, 3, 420–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, H. , Gray, S.N. and Crump, D.H. (2003) Interactions between nematophagous fungi and consequences for their potential as biological agents for the control of potato cyst nematodes. Mycol. Res. 107, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenczmionka, N.J. , Maier, F.J. , Losch, A.P. and Schafer, W. (2003) Mating, conidiation and pathogenicity of Fusarium graminearum, the main causal agent of the head‐blight disease of wheat, are regulated by the MAP kinase gpmk1. Curr. Genet. 43, 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J. , Park, S.Y. , Chi, M.H. , Choi, J. , Park, J. , Rho, H.S. , Kim, S. , Goh, J. , Yoo, S. , Choi, J. , Park, J.Y. , Yi, M. , Yang, S. , Kwon, M.J. , Han, S.S. , Kim, B.R. , Khang, C.H. , Park, B. , Lim, S.E. , Jung, K. , Kong, S. , Karunakaran, M. , Oh, H.S. , Kim, H. , Kim, S. , Park, J. , Kang, S. , Choi, W.B. , Kang, S. and Lee, Y.H. (2007) Genome‐wide functional analysis of pathogenicity genes in the rice blast fungus. Nat. Genet. 39, 561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.S. , Mitchell, T.K. and Dean, R.A. (2007) The Magnaporthe grisea snodprot1 homolog, MSP1, is required for virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273, 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, P. and Zitter, T.A. (2005) First report of Plectosporium blight on pumpkin and squash caused by Plectosporium tabacinum in New York. Plant Dis. 89, 432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kan, J.A.L. (2006) Licensed to kill: the lifestyle of a necrotrophic plant pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman, S.J. , Subbarao, K.V. , Kang, S. , Veronese, P. , Gold, S.E. , Thomma, B.P. , Chen, Z. , Henrissat, B. , Lee, Y.H. , Park, J. , Garcia‐Pedrajas, M.D. , Barbara, D.J. , de Anchieta, A., Jonge, R. , Santhanam, P. , Maruthachalam, K. , Atallah, Z. , Amyotte, S.G. , Paz, Z. , Inderbitzin, P. , Hayes, R.J. , Heiman, D.I. , Young, S. , Zeng, Q. , Engels, R. , Galagan, J. , Cuomo, C.A. , Dobinson, K.F. and Ma, L.J. (2011) Comparative genomics yields insights into niche adaptation of plant vascular wilt pathogens. Plos Pathog. 7, e1002137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krügel, H. , Fiedler, G. , Smith, C. and Baumberg, S. (1993) Sequence and transcriptional analysis of the nourseothricin acetyltransferase‐encoding gene nat1 from Streptomyces noursei . Gene, 127, 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, C.B. , Mitchell, T.K. , Craven, K.D. , Cho, Y. , Cramer, R.A. Jr and Kim, K.‐H. (2008) At death's door: Alternaria pathogenicity mechanisms. Plant Pathol. J. 24, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lazo, G.R. , Stein, P.A. and Ludwig, R.A. (1991) A DNA transformation‐competent Arabidopsis genomic library in Agrobacterium . Biotechnology, 9, 963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Zhou, Z. , Liu, G. , Zheng, F. and He, C. (2007) Characterization of T‐DNA insertion patterns in the genome of rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . Curr. Genet. 51, 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipka, V. , Dittgen, J. , Bednarek, P. , Bhat, R. , Wiermer, M. , Stein, M. , Landtag, J. , Brandt, W. , Rosahl, S. , Scheel, D. , Llorente, F. , Molina, A. , Parker, J. , Somerville, S. and Schulze‐Lefert, P. (2005) Pre‐ and postinvasion defenses both contribute to nonhost resistance in Arabidopsis. Science, 310, 1180–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente, F. , Alonso‐Blanco, C. , Sánchez‐Rodríguez, C. , Jordá, L. and Molina, A. (2005) ERECTA receptor‐like kinase and heterotrimeric G protein from Arabidopsis are required for resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina . Plant J. 43, 165–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente, F. , Muskett, P. , Sánchez‐Vallet, A. , Lopez, G. , Ramos, B. , Sánchez‐Rodríguez, C. , Jordá, L. , Parker, J. and Molina, A. (2008) Repression of the auxin response pathway increases Arabidopsis susceptibility to necrotrophic fungi. Mol. Plant 1, 496–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.J. , van der Does, H.C. , Borkovich, K.A. , Coleman, J.J. , Daboussi, M.J. , Di Pietro, A. , Dufresne, M. , Freitag, M. , Grabherr, M. , Henrissat, B. , Houterman, P.M. , Kang, S. , Shim, W.B. , Woloshuk, C. , Xie, X. , Xu, J.R. , Antoniw, J. , Baker, S.E. , Bluhm, B.H. , Breakspear, A. , Brown, D.W. , Butchko, R.A. , Chapman, S. , Coulson, R. , Coutinho, P.M. , Danchin, E.G. , Diener, A. , Gale, L.R. , Gardiner, D.M. , Goff, S. , Hammond‐Kosack, K.E. , Hilburn, K. , Hua‐Van, A. , Jonkers, W. , Kazan, K. , Kodira, C.D. , Koehrsen, M. , Kumar, L. , Lee, Y.H. , Li, L. , Manners, J.M. , Miranda‐Saavedra, D. , Mukherjee, M. , Park, G. , Park, J. , Park, S.Y. , Proctor, R.H. , Regev, A. , Ruiz‐Roldan, M.C. , Sain, D. , Sakthikumar, S. , Sykes, S. , Schwartz, D.C. , Turgeon, B.G. , Wapinski, I. , Yoder, O. , Young, S. , Zeng, Q. , Zhou, S. , Galagan, J. , Cuomo, C.A. , Kistler, H.C. and Rep, M. (2010) Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium . Nature, 464, 367–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruthachalam, K. , Nair, V. , Rho, H.S. , Choi, J. , Kim, S. and Lee, Y.H. (2008) Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation in Colletotrichum falcatum and C. acutatum . J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 234–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.J. , Brick, M.A. , Byrne, P.F. , Schwartz, H.F. , Shan, X. , Ogg, J.B. and Hensen, R. (2007) Quantitative trait loci linked to white mold resistance in common bean. Crop Sci. 47, 2285–2294. [Google Scholar]

- Mendgen, K. , Hahn, M. and Deising, H. (1996) Morphogenesis and mechanisms of penetration by plant pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 34, 367–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza‐Mendoza, A. , Pozo, M.J. , Grezegorski, D. , Martinez, P. , García, J.M. , Olmedo‐Monfil, V. , Cortes, C. , Kenerley, C. and Herrera‐Estrella, A. (2003) Enhanced biocontrol activity of Trichoderma through inactivation of a mitogen‐activated protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 15 965– 15 970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y. , Patel, G. , Heist, M. , Betts, M.F. , Tucker, S.L. , Galadima, N. , Donofrio, N.M. , Brown, D. , Mitchell, T.K. , Li, L. , Xu, J.‐R. , Orbach, M. , Thon, M. , Dean, R.A. and Farman, M.L. (2007) A systematic analysis of T‐DNA insertion events in Magnaporthe oryzae . Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 1050–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michielse, C.B. , van den Hooykaas, P.J., Hondel, C.A. and Ram, A.F. (2005) Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation as a tool for functional genomics in fungi. Curr. Genet. 48, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michielse, C.B. , van Wijk, R. , Reijnen, L. , Cornelissen, B. and Rep, M. (2009) Insight into the molecular requirements for pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lycopersici through large‐scale insertional mutagenesis. Genome Biol. 10, R4, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micic, Z. , Hahn, V. , Bauer, E. , Schon, C.C. , Knapp, S.J. , Tang, S. and Melchinger, A.E. (2004) QTL mapping of Sclerotinia midstalk‐rot resistance in sunflower. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 1474–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, J.M. and Sikora, E.J. (2003) First report of Plectosporium blight on pumpkin caused by Plectosporium tabacinum in Alabama. Plant Dis. 87, 749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, E.D. , Chen, X. , Romaine, P. , Raina, R. , Geiser, D.M. and Kang, S. (2001) Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Fusarium oxysporum: an efficient tool for insertional mutagenesis and gene transfer. Phytopathology, 91, 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ospina‐Giraldo, M.D. , Mullins, E. and Kang, S. (2003) Loss of function of the Fusarium oxysporum SNF1 gene reduces virulence on cabbage and Arabidopsis . Curr. Genet. 44, 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm, M.E. , Gams, W. and Nierenberg, H.I. (1995) Plectosporium, a new genus for Fusarium tabacinum, the anamorph of Plectosphaerella cucumerina . Mycologia, 87, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Perchepied, L. , Balague, C. , Riou, C. , Claudel‐Renard, C. , Riviere, N. , Grezes‐Besset, B. and Roby, D. (2010) Nitric oxide participates in the complex interplay of defense‐related signaling pathways controlling disease resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Arabidopsis thaliana . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 23, 846–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce de Leon, I. , Oliver, J.P. , Castro, A. , Gaggero, C. , Bentancor, M. and Vidal, S. (2007) Erwinia carotovora elicitors and Botrytis cinerea activate defense responses in Physcomitrella patens . BMC Plant Biol. 7, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado, R. , Rioboo, C. , Herrero, C. and Cid, A. (2011) Characterization of cell response in Chlamydomonas moewusii cultures exposed to the herbicide paraquat: induction of chlorosis. Aquat. Toxicol. 102, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, B. , Alves‐Santos, F.M. , Garcia‐Sanchez, M.A. , Martin‐Rodrigues, N. , Eslava, A.P. and Diaz‐Minguez, J.M. (2007) The gene coding for a new transcription factor (ftf1) of Fusarium oxysporum is only expressed during infection of common bean. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 864–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reignault, P. , Valett‐Collet, O. and Boccara, M. (2008) The importance of fungal pectinolytic enzymes in plant invasion, host adaptability and symptom type. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 120, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rieu, I. and Powers, S.J. (2009) Real‐time quantitative RT‐PCR: design, calculations, and statistics. Plant Cell, 21, 1031–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, H.C. and Kliebenstein, D.J. (2008) Complex genetics control natural variation in Arabidopsis thaliana resistance to Botrytis cinerea . Genetics, 180, 2237–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J. , Fristsch, E.F. and Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory ; Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez‐Rodríguez, C. , Estevez, J.M. , Llorente, F. , Hernández‐Blanco, C. , Jorda, L. , Pagan, I. , Berrocal, M. , Marco, Y. , Somerville, S. and Molina, A. (2009) The ERECTA receptor‐like kinase regulates cell wall‐mediated resistance to pathogens in Arabidopsis thaliana . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 953–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez‐Vallet, A. , Ramos, B. , Bednarek, P. , Lopez, G. , Pislewska‐Bednarek, M. , Schulze‐Lefert, P. and Molina, A. (2010) Tryptophan‐derived secondary metabolites in Arabidopsis thaliana confer non‐host resistance to necrotrophic Plectosphaerella cucumerina fungi. Plant J. 63, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T. , Inaba, T. , Mori, M. , Watanabe, K. , Tomioka, K. and Hamaya, E. (2005) Plectosporium blight of pumpkin and ranunculus caused by Plectosporium tabacinum . J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 71, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Seong, E.S. , Guo, J. , Kim, Y.H. , Cho, J.H. , Lim, C.K. , Hyun‐Hur, J. and Wang, M.H. (2007) Regulations of marker genes involved in biotic and abiotic stress by overexpression of the AtNDPK2 gene in rice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 363, 126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smither‐Kopperl, M.L. , Charudattan, R. and Berger, R.D. (1999) Plectosporium tabacinum, a pathogen of the invasive aquatic weed Hydrilla verticillata in Florida. Plant Dis. 83, 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M. , Dittgen, J. , Sanchez‐Rodriguez, C. , Hou, B.H. , Molina, A. , Schulze‐Lefert, P. , Lipka, V. and Somerville, S. (2006) Arabidopsis PEN3/PDR8, an ATP binding cassette transporter, contributes to nonhost resistance to inappropriate pathogens that enter by direct penetration. Plant Cell, 18, 731–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, J.S. , England, G.K. and McGovern, R.J. (2007) Plectosporium Blight of Cucurbits. UF Department of Plant Pathology, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. P237: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Talhinhas, P. , Muthumeenakshi, S. , Neves‐Martins, J. , Oliveira, H. and Sreenivasaprasad, S. (2008) Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation and insertional mutagenesis in Colletotrichum acutatum for investigating varied pathogenicity lifestyles. Mol. Biotech. 39, 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton, J. and Mauch‐Mani, B. (2004) Beta‐amino‐butyric acid‐induced resistance against necrotrophic pathogens is based on ABA‐dependent priming for callose. Plant J. 38, 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudzynski, P. and Kokkelink, L. (2009) Botrytis cinerea: molecular aspects of a necrotrophic life style In: Plant Relationships V, 2nd edn. (Deising H.B., ed.), pp. 29–50. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, S. , Maccaroni, M. and Belisario, A. (2007) First report of zucchini collapse by Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae Race 1 and Plectosporium tabacinum in Italy. Plant Dis. 91, 325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B. , Tudzynski, B. , van Tudzynski, P. and Kan, J.A.L. (2007) Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 561–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.‐R. , Peng, Y.‐L. , Dickman, M.B. and Sharon, A. (2006) The dawn of fungal pathogen genomics. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 337–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, Y.A. , El‐Tarabily, K.A. and Hussein, A.M. (2001) Plectosporium tabacinum root rot disease of white lupine (Lupinus termis Forsk.) and its biological control by Streptomyces species. J. Phytopathol. 149, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. , Hull, A.K. , Gupta, N.R. , Goss, K.A. , Alonso, J. , Ecker, J.R. , Normanly, J. , Chory, J. and Celenza, J.L. (2002) Trp‐dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev. 16, 3100–3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Karyotype of nonadapted Plectosphaerella cucumerina isolates.

Fig. S2 Arabidopsis mesophyll degradation on Plectosphaerella cucumerina infection.

Fig. S3 Plasmid vectors used for fungal transformation.

Fig. S4 Colonization of Arabidopsis roots by PcBMM‐GFP.

Fig. S5 Analysis of fungal infection progression by confocal microscopy.

Fig. S6 Lambda scanning of fluorescent signals of PcBMM‐GFP‐inoculated leaves.

Fig. S7 T‐DNA insertion flanking sequences from PcBMM‐DON and PcBMM‐DONG mutants.

Table S1 blast similarity of T‐DNA insertion sequences of PcBMM mutants