Abstract

The surface properties of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):(polystyrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) affect the performance of many organic electronic devices. The work function determines the efficiency of the charge carrier transfer between PEDOT:PSS electrodes and the active layer of the device. The surface free energy affects phase separation in multicomponent blends that are typically used to fabricate active layers of organic light-emitting diodes and photovoltaic devices. Here, we present a method to prepare PEDOT:PSS films with a gradient work function and surface free energy. This modification was achieved by evaporation of trimethoxy(3,3,3-trifluoropropyl)silane in such a way that the degree of surface coverage of the molecules varied in the selected direction. Gradient films were used as electrodes to fabricate two-terminal PEDOT:PSS/poly(3-hexyl thiophene)/Au devices to rapidly screen for the influence of the modification on the performance of the prepared polymer diodes. Gradual changes in the morphology of the solution-cast model poly(3-butyl thiophene)/poly-bromostyrene films followed changes in the surface energy of the substrate.

Introduction

Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):(polystyrene sulfonate), better known as PEDOT:PSS, is one of the most widely used conductive polymers in organic electronics. Its unique electro-optical properties, such as its high electrical conductivity and superior optical transparency in the visible light range, make it applicable in energy storage devices,1 organic field transistors, organic light-emitting diodes (OLED),2 and organic photovoltaic devices (OPV).2 In many applications, PEDOT:PSS layers act as transparent electrodes, in most cases with a supporting solution-cast active layer of OLED and OPV. The overall performance of optoelectronic devices depends on many factors, but the most important are the morphology of the active layer and the energy level matching for charge carrier injection/collection. The morphology of solution-processed active layers of donors and acceptors depends on interactions at the internal and external interfaces. Studies of model conjugated-insulating polymer blends have shown that the latter can be tuned by adjusting the surface free energy of the substrate.3 The formation of self-assembled monolayers (SAM) is one of the most effective methods to achieve this goal. SAMs have been used to adjust the energy levels of inorganic electrode-interfacing organic semiconductors.4

Several reported attempts to improve the performance of organic optoelectronic devices have focused on homogenous modification of the PEDOT:PSS layer or its surface to improve the electrical contact with the active layers. The easiest method to modify PEDOT:PSS properties is to mix its dispersion in water with an additional component prior to casting it on a substrate.5−8 It has been reported that glycerol mixed with PEDOT:PSS increases the conductivity and improves the efficiency of polymer light-emitting diodes and photovoltaic devices.6,7 This is explained by a change in the work function (WF) due to surface segregation of PSS.7 Systematic studies by Pathak and co-workers have shown that doping PEDOT:PSS with organic solvents increases its conductivity and modifies the injection barrier at the interface with p-type silicon.9

To modify the free surface of a PEDOT:PSS layer, evaporation, solution casting, and dipping methods can be used. A thin layer of M-phthalocyanine evaporated on top of PEDOT:PSS increases the absorption at longer wavelengths and the open circuit voltage of poly[bis(3-dodecyl-2-thienyl)-2,2′-dithiophene-5,5′-diyl]:phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PQT-12:PCBM)-based photovoltaic devices.10 An ultrathin layer of fluorinated polyimide lowers the hole injection barrier at the interface between PEDOT:PSS and poly(9,9-dioctylfluorene-2,7-diyl-co-2,5-di(phenyl-4′-yl)-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole) when used as an active layer in polymer light-emitting diodes.11 A thin layer of a DNA complex on PEDOT:PSS enhances the brightness of green and blue OLEDs.12 Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) increases the crystallization of poly(3-hexyl thiophene) (P3HT):PCBM during thermal annealing, and this effect is responsible for the increased short-circuit current and higher power conversion efficiency of solar cells with a 4 nm layer of PVDF at the interface between the anode and active layer.13 Recently, Lee and co-workers showed that a trichloro(octadecyl)silane interlayer improves the performance of blue light-emitting diodes by promoting hole injection from the anode into the active layer.14 Zhang et al. successfully changed the charge selectivity of the electrode and fabricated inverted solar cells with polyethylenimine (PEIE)-modified PEDOT:PSS as cathode.15 Another method to modify properties of PEDOT:PSS was recently proposed by Moulé and co-workers.16 They demonstrated that PSS segregated to the free surface mix with conjugated polymers upon thermal treatment, forming an insoluble interlayer which affects the performance of the photovoltaic cell formed on top.16

The vast majority of work on the surface modification of PEDOT:PSS has focused on the problem of anode and active-layer energy-level matching. Relatively little attention has been paid to the influence of surface energy modifications on the microstructure formation process during the fabrication of the active layer. Zhang et al. have shown that thin layer of PEIE increases the interfacial contact between PEDOT:PSS and P3HT:PCBM and affects the morphology of OPV active layer.15 The authors proposed also a method to tune the surface free energy of modified PEDOT:PSS by varying the pH value of PEIE solution.15 Wang and co-workers proved that the surface energy patterns formed at the PEDOT:PSS by microcontact printing can enforce the ordering of structures in thin films of conjugated polymers.17 This idea was used by Chen to control phase separation in a P3HT:PCBM blend.18 The authors showed that patterns of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane self-assembled monolayers can induce self-ordering of the phase domains in active layers of polymer solar cells. They observed an increased efficiency in devices with P3HT stripes surrounded by a PCBM-rich phase.

Optimization of the fabrication conditions when many parameters influence the overall performance requires preparation and testing of multiple devices. The use of samples with a gradient of physicochemical properties, called chemical libraries, can speed up this process. This approach has also been applied successfully to optimize the fabrication of organic optoelectronic devices,19−21 mostly to optimize the composition of devices based on low-molecular-weight compounds deposited by thermal evaporation.19−21

Here, we present a method to fabricate PEDOT:PSS films with a gradient of work function and surface free energy, i.e., the two factors that directly (wok function) and indirectly (by influencing the phase separation of active layer components) determine the performance of organic electronic devices. The polymer surface was modified by evaporation of volatile silane molecules in an adapted dip-coating setup. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) showed a gradient in the silane surface coverage. The work function measured by ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) reached a maximum value for approximately 15% of the fluorine surface concentration, as measured by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Contact angle measurements showed monotonous growth of the surface free energy within the achieved surface coverage. The performance of the PEDOT:PSS/P3HT/Au devices prepared on a modified substrate changed with the position on the electrode following the spatial variation in the work function. The morphology of the model poly(3-butyl thiophene)/poly-bromostyrene blend solution cast on the modified substrate reflected the local surface free energy of the substrate.

Results and Discussion

Homogenous Modification

Homogenous modification of the PEDOT:PSS surface was obtained by evaporation of silane molecules from a toluene solution, which is a method that was successfully used previously to functionalize the surface of organic semiconductors.22 The polymer films prepared on silicon wafers or indium tin oxide (ITO)-covered glass were attached horizontally to the lid of the weighing cell. The cell was filled with a 10 mM solution of trimethoxy(3,3,3-trifluoropropyl)silane (3FS) and immediately closed; the distance between the sample and the free surface of the solution was ca. 1 cm. All deposition experiments were carried out in air at room temperature beneath a fume hood.

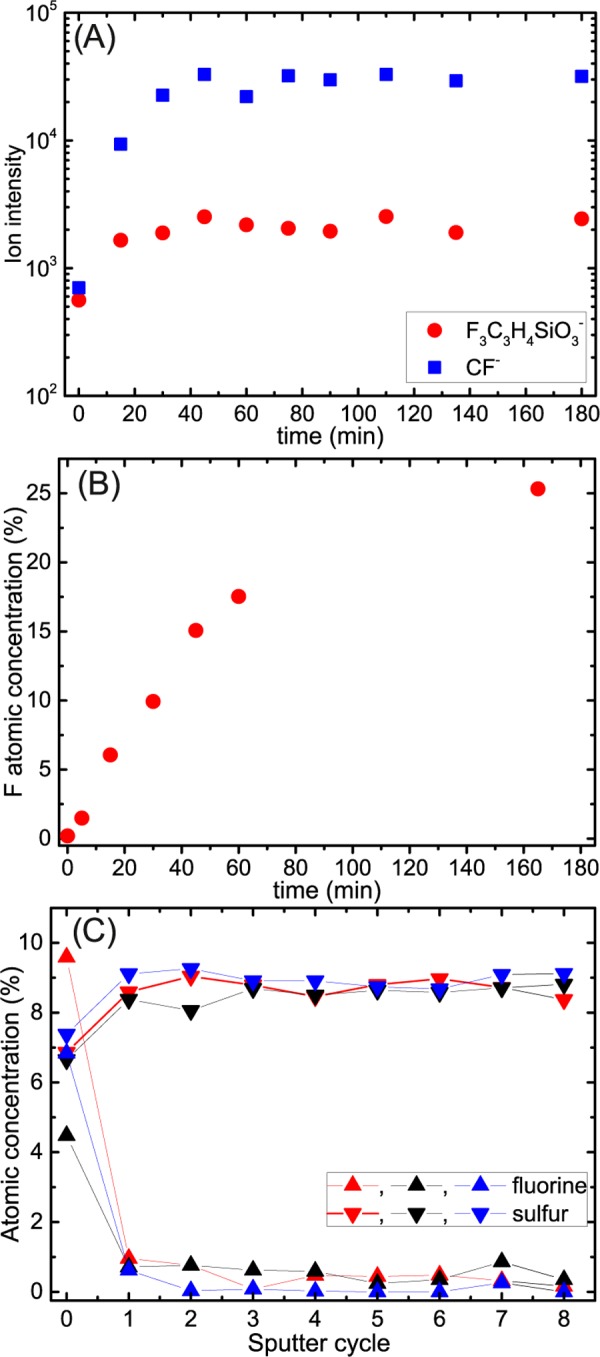

The number of 3FS molecules deposited on the surface as a function of the evaporation time was tracked using the static mode of secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). In the first method, the sample surface was bombarded with Bi3+ ions (energy 30 keV) and the emerging ionized fragments were analyzed in a time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer. Typically, in SIMS spectra of SAM adsorbed on solid surfaces, signals corresponding to characteristic fragments of the molecule are visible along with the others corresponding to whole molecules, clusters of molecules and atoms of the substrate.23 For silane adsorbed on a soft PEDOT:PSS substrate, the SIMS spectra also contain fragments of the polymer that often interfere with the signals coming from the SAM. In the present study, two fragments derived from 3FS molecules were tracked, F3C3H4SiO3– and CF–, as presented in Figure 1A. An initial rapid increase in both signals is followed by their saturation after 50 min of vapor treatment. In contrast, the XPS spectra show continuous increases in the fluorine atomic concentration at the surface for up to 160 min (Figure 1B) and this increase is accompanied by the decay of the sulfur signal (S 2p) characteristic of PEDOT:PSS24 and increase in silicon (Si 2p, line at 102 eV) and F3C*–CH2 (line at 292.5 eV) signals25 (see Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Evaporation of 3FS molecules on PEDOT:PSS: (A) F3C3H4SiO3–, CF– s-SIMS signals. (B) Fluorine surface atomic concentration calculated from XPS spectra (see Figure S1) as a function of evaporation time. (C) Fluorine and sulfur XPS profiles; eight sputtering cycles correspond to 20 nm crater depth.

To ensure that the silane molecules only adsorbed on the surface, modified PEDOT:PSS films were sputtered using an argon cluster ion beam, and the XPS spectra of the layers sputtered for different times were recorded. In contrast to monoatomic ion beams, the gas cluster ion beam does not destroy chemical bonds in organic materials, allowing the collection of depth profiles of the chemical composition of the studied samples.26−28 In Figure 1C, the atomic concentrations of fluorine and sulfur were plotted as a function of the sputter time; the eight cycles of sputtering led to the formation of a crater approximately 20 nm deep. The rapid decrease in fluorine signal already observed in the first sputtering cycle indicates that the 3FS molecules adsorbed selectively on the surface and did not penetrate the PEDOT:PSS film.

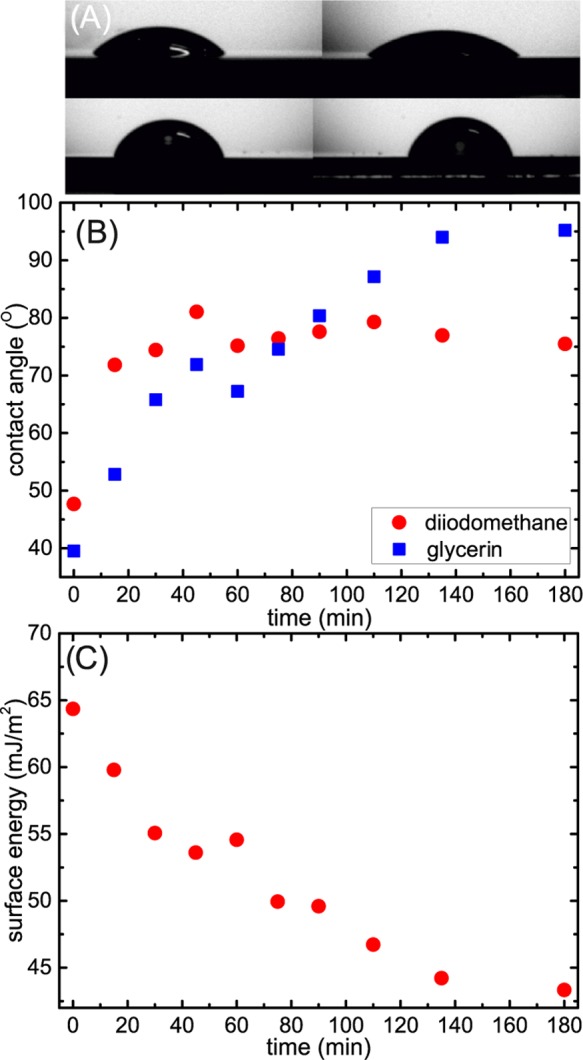

The surface energy and electronic properties of the 3FS-modified PEDOT:PSS layer were studied using contact-angle measurements and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS), respectively. Figure 2A presents the change in the shape of the diiodomethane and glycerol droplets placed on the prepared and modified PEDOT:PSS layers deposited on a flat silicon wafer. The evolution of the contact angle of both liquids on the PEDOT:PSS surface as a function of the evaporation time is presented in Figure 2B. Glycerol and diiodomethane were chosen as the polar and nonpolar liquids (water dissolves the bare PEDOT:PSS surface and could not be used in this experiment). The contact angle of diiodomethane increased from approximately 48 to 84° after 50 min of 3FS evaporation and remained constant for longer times, whereas the value of the contact angle for glycerin continued to increase from <40 up to 95° for the samples exposed to silane vapor for 180 min. The measured values of the contact angles were used to calculate the surface free energy of the 3FS-modified PEDOT:PSS surfaces according to the Owens and Wendt model29 presented in Figure 2C. The surface free energy of the modified layers monotonically decreased with the time of exposure to 3FS vapor, i.e., from 65 mJ/m2 for the prepared samples to 42.5 mJ/m2 for the layers saturated for 180 min.

Figure 2.

Influence of 3FS on surface free energy of PEDOT:PSS films: (A) diiodomethane (left column) and glycerol (right column) droplets placed on prepared (top row) and modified PEDOT:PSS (bottom row) layer deposited on flat silicon wafer, (B) contact angle of diiodomethane (red circles) and glycerol (blue squares) droplets placed on modified PEDOT:PSS film as a function of evaporation time, and (C) surface free energy calculated according to Owens, Wendt model.

The variation of surface interactions induced by modified PEDOT:PSS are scarcely reported. Petrosino and Rubino observed slight changes in total surface energy (71.65–73.43 mJ/m2) for films with different PEDOT:PSS ratios.30 Zhang and co-workers controlled hydrophilicity of PEIE-modified PEDOT:PSS in a wide range of contact angles (from 25° up to 50°)15 by changing pH of the PEIE solution. The variation of surface energy obtained by our method, between 65 mJ/m2 (pristine) and 42.5 mJ/m2 (modified), can be compared with previous reports on the surface tension-induced modification of phase separation in blends of poly(3-alkylthiophene) (P3AT) with insulating polystyrene (PS), leading to formation of lateral (2D) and lamellar (L) morphology.3 Even much lower differences in surface energy could induce such blend morphology changes: between 35.4 mJ/m231 (SiOx, 2D) and 45 mJ/m232 (Au, L, P3AT on bottom) for PS/P3BT or between 35.4 mJ/m231 (SiOx, 2D) and 24 mJ/m233 (SAM-CH3, L, P3AT on top) for PS/poly(3-hexyl thiophene) (RP3HT) or between 24 mJ/m233 (SAM-CH3, 2D) and 45 mJ/m232 (Au, L, P3AT on bottom) for PS/P3DDT, respectively.3

The ultraviolet photoelectron spectra presented in Figure 3A show that a buildup of the 3FS layer changed the energy required by an electron to escape from the PEDOT:PSS surface. The work function (WF) of the modified polymer calculated as the difference between the secondary electron cutoff and the energy of the incident photon is plotted as a function of the evaporation time in Figure 3B. In the case of inorganic electrodes, the change in WF results from the buildup of an electric dipole on the SAM-covered surface.34 In the presented experiment, the work function first increased from 4.85 to 5.5 eV for a sample exposed to 3FS vapor for 45 min and later decreased to less than 5.0 eV for 165 min of vapor deposition. This observation can be explained as a buildup of the second layer of 3FS molecules that begins after 45 min of vapor modification.35 In this case, the dipole moment of the second stratum should have the opposite direction. Reorganization of the silane layer on the PEDOT:PSS surface is another possible explanation.36 The onset of this process corresponds to a fluorine surface concentration of approximately 15%, as measured by XPS.

Figure 3.

(A) Secondary electron cutoff as acquired by UPS (He I, 21.22 eV), (B) work function of modified PEDOT:PSS calculated as difference between secondary electron cutoff and energy of incident photon as a function of evaporation time.

Heterogeneous Modification

Homogenous samples with different surface properties were prepared using vapor deposition. An alternative method to form self-assembled monolayers is incubation in solution. Changing the incubation time with slow dipping in a SAM solution leads to the formation of samples with a coverage gradient. However, as shown here, evaporation from a diluted silane solution is a very effective method to modify PEDOT:PSS with 3FS molecules, limiting the usage of the slow dipping method to gradually modify the surface properties of PEDOT:PSS. Test experiments have shown that slow immersion of PEDOT:PSS films in a 3FS solution leads to the formation of layers with slight changes in the surface composition or the formation of inverted gradients, i.e., the fragments submerged longer in solution were covered with fewer 3FS molecules than those submerged for shorter times; see Figure S2. It shows importance of formation in vapors rather than in liquid.

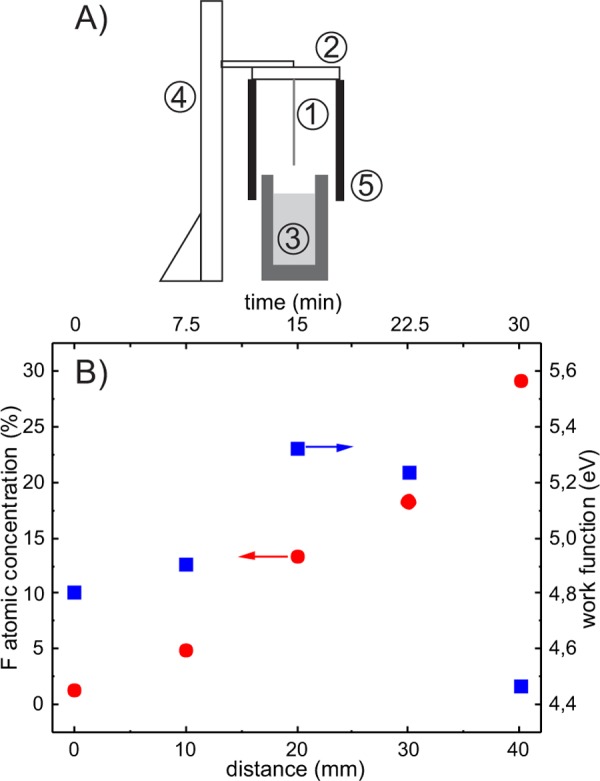

To heterogeneously fabricate a modified PEDOT:PSS surface using vapor deposition, a part of the film must be isolated from the silane vapor. This can be achieved simply by partial immersion in a container with a liquid that does not dissolve the polymer and does not alter its properties significantly. A sketch of a specially designed dip-coater is shown in Figure 4A. The longitudinal sample (1) was fixed vertically to the lid (2) and slowly lowered into a thick-walled container (3) filled with toluene using a linear stage (4). A recess was created on the edge of the container, and a small amount of 3FS was placed in the recess to evaporate. A cylindrical shield (5) was attached to the lid to limit the volume of the vapor. Typically, the immersion time was up to 30 min, and at the end, the sample was quickly raised, washed with toluene, and blow-dried with nitrogen. Test experiments have shown that the method developed here can be used to prepare heterogenous surfaces modified with various volatile silanes.

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic drawing of dip-coater used to fabricate films with gradient of silane coverage: (1) sample, (2) lid, (3) thick-wall container filled with toluene, (4) linear stage, and (5) shield. (B) Variation of fluorine atomic concentration (red circles, left axis) and work function (blue squares, right axis) as a function of distance (bottom axis) and vapor exposition time (top axis); original XPS and UPS spectra are presented in Figure S2.

The XPS spectra presented in Figure S3 prove that the surface composition of the fabricated samples changed monotonically with the distance from the lower edge. Quantitatively, the variation of the fluorine atomic concentration (left axis) as a function of the distance (bottom axis) and vapor exposure time (top axis) is presented in Figure 4B. The linear growth of the 3FS layer is similar to that of the one described in Figure 1B, but in this case, the growth rate of the silane layer is higher. After 30 min, the concentration of fluoride at the surface reached almost 30%. The faster growth of the silane layer is likely due to the higher concentration of 3FS vapor in the air volume above toluene than that in the previous experiment. The same plot presents the variation in the work function (right axis) on the modified surface, and the original UPS spectra are presented in Figure S4. Similar to the previous experiment, the work function also increased up to 5.3 eV at the point located 20 mm from the upper edge and decreased down to 4.4 eV for the longer evaporation time. The changes in the work function obtained in the experiment significantly exceed those reported previously for PEDOT:PSS films with different component ratios: 4.75–5.15 eV,30 admixed with different compounds prior to solution coating (ΔWF −0.12 eV)8 and close to that observed for PEIE-modified layers, i.e., 4.1–5.1 eV.15

Immersion in toluene may both modify the surface properties of PEDOT:PSS and leach physisorbed molecules from the surface. The test experiments showed that the UPS spectrum of unmodified PEDOT:PSS only slightly changed after 30 min of immersion in toluene compared to that in the untreated group, which indicated that the toluene bath does not shift the work function. In turn, the XPS spectra of the polymer layer modified by vapor deposition of 3FS molecules after the same toluene treatment showed a decrease in the fluorine and silicon concentrations, which was accompanied by an increase in the sulfur content. This points to a partial washout of molecules loosely bound to the surface. Therefore, when comparing the effect of the 3FS modification obtained using the two methods discussed above, the time of the vapor treatment is not a useful parameter. Instead, when the values of the work function measured for the samples prepared via different methods are plotted against the fluorine surface concentration, they fall nicely on a single master curve, as presented in Figure 5. The additional measurements of the contact potential difference (CPD) obtained using the Kelvin probe for samples prepared by vapor deposition followed the same trend.

Figure 5.

Work function (WF) and contact potential difference (CPD) as a function of fluorine surface concentration measured by XPS for homogenous samples prepared by evaporation (blue symbols) and films gradually covered with 3FS molecules.

Devices and Phase Separation—Chemical Library Approach

As a proof of concept, we verified the influence of the 3FS modification on the electrical properties of the PEDOT:PSS electrode and the phase separation that occurred in a polymer blend casted on top. The PEDOT:PSS layers were prepared on top of longitudinal substrates and later modified with 3FS according to the procedure described in the previous section to fabricate a gradient of surface energy and work function. The 75 mm long Osilla scale-up glass slides with patterned ITO were used as the substrates for the electrical measurements, and strips of silicon wafers were used as the substrates in the phase separation studies.

Regio-regular poly(3-hexyl thiophene) (RP3HT) was spin-coated from a chlorobenzene solution in an argon-filled glovebox. The edges of each sample were wiped clean to provide electrical contacts with gold electrodes thermally evaporated through a shadow mask in the final step of the fabrication. A photo of a substrate with 12 pixels is shown in Figure 6A. At the beginning of the experiment, the lower edge of the substrate touched the free surface of toluene. Taking into account the dipping velocity, the time of exposure to 3FS vapor was estimated for each pixel (center of the pixel) and is presented in the image. Because of the shallow depth of the container, the last pixel was not immersed in toluene. The I–V curves were measured in an inert atmosphere for each of the devices and are plotted in Figure 6B.

Figure 6.

Performance of PEDOT:PSS/P3HT/Au devices prepared on substrate with gradient of 3FS surface coverage: (A) photo of 12 devices (numbers correspond to evaporation time in min), (B) current–voltage characteristic measured for each of device, (C) forward current IFOR (right axis) and rectification ratio (RR) (left axis) as a function of the device number. Morphology of P3BT/PBrS films cast on bare (D–F) and modified (G–I) PEDOT:PSS: (D, G) SIMS depth profiles, 2D composition maps of sulfur (E, H) and bromine (F, I).

The first conclusion from the analysis of the presented I–V curves is that the current flowing through the PEDOT:PSS/3FS/RP3HT/Au device diminishes as the 3FS concentration increases on the PEDOT:PSS surface. Quantitatively, the forward current measured at the +1 V bias decreases logarithmically with the pixel number, as presented in Figure 6C. This observation can be rationalized in terms of an increased tunneling barrier for the charge carriers introduced by short alkyl chains deposited on the PEDOT:PSS electrode. As the thickness of the barrier increases linearly with evaporation time (Figure 2B) and the tunneling current decreases exponentially with tunneling distance, exponential decay in the current is expected.

In contrast, with the symmetric current–voltage characteristics typically observed for SAM layers,37 a slight asymmetry can be seen in the curves presented in Figure 6B. This asymmetry reflects the asymmetry in the work function of the electrodes confined in the RP3HT layer. A detailed analysis of the currents at +1 and −1 V indicates a decrease in the rectification ratio (RR), which is defined as a ratio of the currents measured in the forward and reverse bias, RR = IFOR/IREV, from a value of approximately 1.7 for the first pixel to a value of approximately 0.7 for the sixth pixel. There was a subsequent increase for the pixels exposed to the 3FS vapor for longer times. This resembles the trend in the work function variation with the increasing 3FS surface concentration, as shown in the UPS and Kelvin probe experiments (Figure 5).

Mixtures of polystyrene and poly(3-alkylthiophene) (P3AT) were used previously in studies on phase separation as model systems to search for self-assembling systems of insulating and conjugated polymers.3,38 Success in the pattern replication experiment would not be possible without former studies on the influence of the surface interactions on the phase structure formed in such blends cast on different substrates.3 Here, a chlorobenzene solution of poly(3-butylthiophene) (P3BT) mixed with brominated polystyrene (PBrS) was used to study the phase separation in polymer blends cast on top of the 3FS-modified PEDOT:PSS surface. The insulating component was labeled with bromine to enhance the contrast visible in the SIMS depth profiles and 2D composition images.

In Figure 6C–I the influence of the decreased surface energy in the modified PEDOT:PSS layer on the morphology of the P3BT/PBrS films is shown. The 2D images obtained for the films prepared on bare PEDOT:PSS surface show a 2D structure with P3BT oval domains dispersed in a PBrS-rich matrix. The corresponding depth profile revealed no wetting layers on the free surface or at the interface with the PEDOT:PSS layer. The depth profile and 2D images acquired for the P3BT/PBrS film cast on PEDOT:PSS exposed to 3FS vapor for 30 min indicate a lamellar structure in which the bottom poly(3-butyl thiophene) layer is covered with a punched brominated polystyrene film. This observation is in agreement with previous reports on P3BT/polystyrene phase behavior, showing that this system forms a bilayer structure when cast on an Au substrate (surface energy 45 mJ/m232), whereas a 2D morphology is observed for samples cast on SiOx (surface energy 35.4 mJ/m231). In the case presented here, the upper PBrS lamellae breaks as a result of a higher mismatch in the interface energy between poly(3-butyl thiophene) and brominated polystyrene.

Conclusions

We have shown that the surface free energy of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):(polystyrene sulfonate) films and their work function can be tailored by vapor deposition of trimethoxy(3,3,3-trifluoropropyl)silane. With the aid of a modified dip-coater, a heterogeneous surface coverage of 3FS was achieved. The work function of the modified PEDOT:PSS changed with the number of silane molecules adsorbed on the surface; the value first increased and then decreased with an increasing concentration of fluoride on the surface. In contrast, a monotonic decrease in the surface free energy was observed within the scope of the experiment.

Heterogeneous silane-modified PEDOT:PSS films with a gradient 3FS surface composition were used as the bottom electrode in PEDOT:PSS/3FS/RP3HT/Au devices and as substrate for solution-casted P3BT/PBrS films. Electrical measurements showed that the change in the work function caused by the adsorption of 3FS molecules influences the performance of all 12 devices prepared on the same electrode. The change in the surface free energy induced a transition from the lateral to lamellar phase separation in solution-cast P3BT/PBrS films. The use of substrates with a gradient of physicochemical properties, called chemical libraries, allows a reduction in the number of samples in systematic studies on the effect of modification on the properties of the devices and the layers prepared on top of them.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation

Silicon wafers with a native silicon dioxide layer (Si-Mat, GmbH, Germany) were cleaned by sonication in toluene (POCh, Gliwice, Poland) for 10 min. Next, the wafers were immersed in a H2O/H2O2/NH3(aq) solution and heated at 75 °C for 15 min, rinsed with deionized water, and dried under a N2 flux. In the last step of the cleaning, the wafers were immersed in a H2O/H2O2/HCl solution, heated at 75 °C for 15 min, rinsed with deionized water, and dried under a N2 flux. ITO-covered glass (Delta Technologies) substrates were cleaned by sonication in 2-propanol for 15 min and dried under N2 flux.

Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):(polystyrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) (Clevios THL Solar dispersion in water – Heraeus GmbH, Germany) was filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter and spun-cast onto prepared substrates at 3000 rpm. The prepared thin films were annealed at 120 °C by 20 min.

Electronic grade poly(3-hexyl thiophene) (RP3HT, Rieke Metals) was dissolved in chlorobenzene to form a 15 mg/mL solution. Before casting, the solution was heated at 60 °C overnight inside an argon-filled glovebox. The prepared solution was spun-cast into prepared PEDOT:PSS thin films covered with a gradient 3FS layer.

Poly(3-butyl thiophene) (P3BT, Rieke Metals) and dPBrS (Polymer Standards Service (PSS) GmbH) were dissolved in chlorobenzene to prepare a 10 mg/mL solution. Both solutions were heated at 60 °C overnight, blended in a 1:1 volume ratio, and spun-cast onto PEDOT:PSS thin films covered with a 3FS gradient layer.

Characterization Techniques

SIMS

Secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) was used to investigate the surface composition of the modified PEDOT:PSS layers and the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the P3BT/PBrS films cast on top.

A secondary ion mass spectrometer with a TOF analyzer TOFSIMS 5 (ION-TOF GmbH, Germany) system working in single-beam or dual-beam mode was used to investigate the surface composition of the modified PEDOT:PSS layers and the 3D structure of the P3BT/PBrS films cast on top. Static SIMS spectra (total dose up to 9 × 1010 ions/cm2) were acquired using a pulsed 30 keV Bi3+ ion beam scanned over a 200 μm × 200 μm area, and the secondary ions were extracted into a reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer before reaching the MCP detector. For each sample, five different areas were examined and used to calculate the intensity of the selected signals. To obtain composition versus depth profiles, 2D map samples were sputtered with a Cs low-energy ion beam (500 eV, 32 nA) rastered over a 300 μm × 300 μm area, exposing the dip layers of the film. The structures revealed in the crater center were analyzed with a focused bismuth beam (imaging mode) rastered over a 100 μm × 100 μm area and a ToF mass spectrometer.

XPS

XPS analyses were performed in a PHI VersaProbeII Scanning XPS system using monochromatic Al Kα (1486.6 eV) X-rays focused to a 100 μm spot and scanned over a sample area of 400 μm × 400 μm. The photoelectron take-off angle was set to 45°, and the pass energy in the analyzer was set to 23.50 eV to obtain high energy resolution spectra for the C 1s, F 1s, Si 2p, and S 2p regions. A UPS analysis was performed using a helium gas-discharge lamp, He 1α (21.22 eV) and He 2α (40.81 eV), under a base pressure of 3 × 10–9 mBar and 4 mm diameter area of analysis. The analyzer pass energy was set to 2.95 eV. Depth profiling was performed by sputtering with a 10 keV Ar 4000 cluster ion beam and 8 mm × 8 mm sample area. The instrumental resolution was determined to be 0.15 eV at a 2.95 eV pass energy using the Fermi edge of the valence band for metallic gold (room temperature). The secondary electron cutoff was determined from the spectrum, and the WF of the material was calculated.

Contact Angle

Static contact angles were measured for two reference liquids: polar glycerol and nonpolar diiodomethane. The experiments were performed by the sessile drop technique using a θ-light instrument at room temperature. Contact angles were determined as the average of 10 measurements taken at different spots on the same sample surface. The Owens–Wendt analytical approach was applied to calculate the surface free energy.

Surface Potential Difference

The contact potential difference was measured using a Kelvin probe (Instytut Fotonowy, Poland) with a 2 mm gold grid reference electrode.

Electrical Characterization

Current–voltage characteristics were measured under an argon atmosphere in a glovebox with a computer-controlled Keithley 2400 source-meter unit.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Science Center under Grant No. 2011/03/B/ST5/01568. The authors thank the Instytut Fotonowy company for enabling measurements of the potential contact differences. The research was performed with equipment purchased thanks to the financial support of the European Regional Development Fund in the framework of the Polish Innovation Economy Operational Program (contract no. POIG.02.01.00-12-023/08).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00029.

XPS and UPS spectra of PEDOT:PSS films modified with 3FS (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sun K.; Zhang S.; Li P.; Xia Y.; Zhang X.; Du D.; Isikgor F. H.; Ouyang J. Review on application of PEDOTs and PEDOT:PSS in energy conversion and storage devices. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2015, 26, 4438–4462. 10.1007/s10854-015-2895-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W.; Li J.; Chen H.; Xue J.. Transparent Electrodes for Organic Optoelectronic Devices: A Review; SPIE, 2014; p 28. [Google Scholar]

- Jaczewska J.; Budkowski A.; Bernasik A.; Raptis I.; Moons E.; Goustouridis D.; Haberko J.; Rysz J. Ordering domains of spin cast blends of conjugated and dielectric polymers on surfaces patterned by soft- and photo-lithography. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 234–241. 10.1039/B811429C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H.; Huang Q.; Cui J.; Veinot J. G. C.; Kern M. M.; Marks T. J. High-Brightness Blue Light-Emitting Polymer Diodes via Anode Modification Using a Self-Assembled Monolayer. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 835–838. 10.1002/adma.200304585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. H.; Mäkinen A. J.; Nikolov N.; Shashidhar R.; Kim H.; Kafafi Z. H. Molecular organic light-emitting diodes using highly conducting polymers as anodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 80, 3844. 10.1063/1.1480100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Johansson M.; Andersson M. R.; Hummelen J. C.; Inganäs O. Polymer Photovoltaic Cells with Conducting Polymer Anodes. Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 662–665. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith H. J.; Kenrick H.; Chiesa M.; Friend R. H. Morphological and electronic consequences of modifications to the polymer anode ‘PEDOT:PSS’. Polymer 2005, 46, 2573–2578. 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.01.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji T.; Tan L.; Hu X.; Dai Y.; Chen Y. A comprehensive study of sulfonated carbon materials as conductive composites for polymer solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 4137–4145. 10.1039/C4CP04965A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak C. S.; Singh J. P.; Singh R. Modification of electrical properties of PEDOT:PSS/p-Si heterojunction diodes by doping with dimethyl sulfoxide. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 652, 162–166. 10.1016/j.cplett.2016.04.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bamsey N. M.; Yuen A. P.; Hor A.-M.; Klenkler R.; Preston J. S.; Loutfy R. O. Integration of an M-phthalocyanine layer into solution-processed organic photovoltaic cells for improved spectral coverage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 1970–1973. 10.1016/j.solmat.2011.01.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Li W.; Yang J.; Fu Y.; Xie Z.; Zhang S.; Wang L. Performance Enhancement of Polymer Light-Emitting Diodes by Using Ultrathin Fluorinated Polyimide Modifying the Surface of Poly(3,4-ethylene dioxythiophene):Poly(styrenesulfonate). J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 7898–7903. 10.1021/jp810824m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen J. A.; Li W.; Steckl A. J.; Grote J. G. Enhanced emission efficiency in organic light-emitting diodes using deoxyribonucleic acid complex as an electron blocking layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 171109 10.1063/1.2197973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S. O.; Yook K. S.; Lee J. Y. Improved efficiency in organic solar cells through fluorinated interlayer induced crystallization. Org. Electron. 2009, 10, 1583–1589. 10.1016/j.orgel.2009.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. H.; Lee W.; Cai G.; Baek S. J.; Han S.-H.; Lee S.-H. Enhanced Performance of Blue Polymer Light-Emitting Diodes by a Self-Assembled Thin Interlayer. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2008, 8, 4842–4845. 10.1166/jnn.2008.IC28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Chen L.; Hu X.; Zhang L.; Chen Y. Low Work-function Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxylenethiophene): Poly(styrene sulfonate) as Electron-transport Layer for High-efficient and Stable Polymer Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12839 10.1038/srep12839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulé A. J.; Jung M.-C.; Rochester C. W.; Tress W.; LaGrange D.; Jacobs I. E.; Li J.; Mauger S. A.; Rail M. D.; Lin O.; Bilsky D. J.; Qi Y.; Stroeve P.; Berben L. A.; Riede M. Mixed interlayers at the interface between PEDOT:PSS and conjugated polymers provide charge transport control. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 2664–2676. 10.1039/C4TC02251C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Östblom M.; Johansson T.; Inganäs O. PEDOT surface energy pattern controls fluorescent polymer deposition by dewetting. Thin Solid Films 2004, 449, 125–132. 10.1016/j.tsf.2003.10.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.-C.; Lin Y.-K.; Ko C.-J. Submicron-scale manipulation of phase separation in organic solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 023307 10.1063/1.2835047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreger K.; Bäte M.; Neuber C.; Schmidt H. W.; Strohriegl P. Combinatorial Development of Blue OLEDs Based on Star Shaped Molecules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 3456–3461. 10.1002/adfm.200700223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuber C.; Bäte M.; Thelakkat M.; Schmidt H.-W.; Hänsel H.; Zettl H.; Krausch G. Combinatorial preparation and characterization of thin-film multilayer electro-optical devices. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2007, 78, 072216 10.1063/1.2756993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hänsel H.; Zettl H.; Krausch G.; Schmitz C.; Kisselev R.; Thelakkat M.; Schmidt H.-W. Combinatorial study of the long-term stability of organic thin-film solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 81, 2106–2108. 10.1063/1.1506203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olaya D.; Sanchez J.; Gershenson M. E.; Calhoun M. F.; Podzorov V. Electronic functionalization of the surface of organic semiconductors with self-assembled monolayers. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 84–89. 10.1038/nmat2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossowski J.; Rysz J.; Krawiec M.; Maciazek D.; Postawa Z.; Terfort A.; Cyganik P. Oscillations in the Stability of Consecutive Chemical Bonds Revealed by Ion-Induced Desorption. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1336–1340. 10.1002/anie.201406053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun D.-J.; Chung J.; Heon Kim S.; Kim Y.; Park S.; Seol M.; Heo S. Direct analytical method of contact position effects on the energy-level alignments at organic semiconductor/electrode interfaces using photoemission spectroscopy combined with Ar gas cluster ion beam sputtering. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 465704 10.1088/0957-4484/26/46/465704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamson G.; Briggs D. High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers: The Scienta ESCA300 Database. J. Chem. Educ. 1993, 70, A25. 10.1021/ed070pA25.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich P. M.; Nietzold C.; Weise M.; Unger W. E. S.; Alnabulsi S.; Moulder J. XPS depth profiling of an ultrathin bioorganic film with an argon gas cluster ion beam. Biointerphases 2016, 11, 029603 10.1116/1.4948341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasik A.; Haberko J.; Marzec M. M.; Rysz J.; Luzny W.; Budkowski A. Chemical stability of polymers under argon gas cluster ion beam and x-ray irradiation. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., B: Nanotechnol. Microelectron.: Mater., Process., Meas., Phenom. 2016, 34, 030604 10.1116/1.4943951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong-Jin Yun; JaeGwan Chung; Seong Heon Kim; Yongsu Kim; SungHoon Park; Minsu Seol; Sung H. Direct analytical method of contact position effects on the energy-level alignments at organic semiconductor/electrode interfaces using photoemission spectroscopy combined with Ar gas cluster ion beam sputtering. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 465704 10.1088/0957-4484/26/46/465704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D. K.; Wendt R. C. Estimation of the surface free energy of polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. 10.1002/app.1969.070130815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino M.; Rubino A. The effect of the PEDOT:PSS surface energy on the interface potential barrier. Synth. Met. 2012, 161, 2714–2717. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2011.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harnett E. M.; Alderman J.; Wood T. The surface energy of various biomaterials coated with adhesion molecules used in cell culture. Colloids Surf., B 2007, 55, 90–97. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W.; Lee J. Effect of oxygen plasma treatment on reduction of contact resistivity at pentacene/Au interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 262102 10.1063/1.2218044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen D.; De Palma R.; Verlaak S.; Heremans P.; Dehaen W. Static solvent contact angle measurements, surface free energy and wettability determination of various self-assembled monolayers on silicon dioxide. Thin Solid Films 2006, 515, 1433–1438. 10.1016/j.tsf.2006.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goh C.; Scully S. R.; McGehee M. D. Effects of molecular interface modification in hybrid organic-inorganic photovoltaic cells. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 114503 10.1063/1.2737977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maoz R.; Sagiv J. Targeted Self-Replication of Silane Multilayers. Adv. Mater. 1998, 10, 580–584. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sushko M. L.; Shluger A. L. Dipole–Dipole Interactions and the Structure of Self-Assembled Monolayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 4019–4025. 10.1021/jp0688557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer B.; de Leeuw D. M.; Akkerman H. B.; Blom P. W. M. Towards molecular electronics with large-area molecular junctions. Nature 2006, 441, 69–72. 10.1038/nature04699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaczewska J.; Budkowski A.; Bernasik A.; Moons E.; Rysz J. Polymer vs solvent diagram of film structures formed in spin-cast poly(3-alkylthiophene) blends. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 4802–4810. 10.1021/ma7022974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.