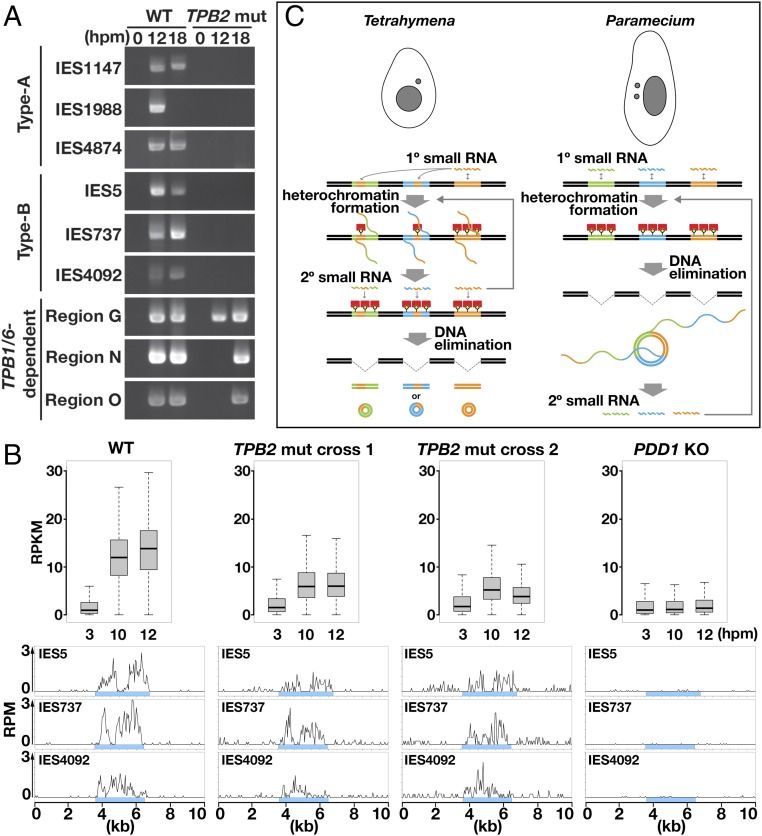

Fig. 4.

Analyses of DNA elimination and late-scnRNA accumulation in TPB2 mutants. (A) WT and TPB2 mutant (TPB2 mut; mating of #41 and #44) strains were mated, and their genomic DNA was extracted at 0, 12, and 18 hpm. The excised circles from the indicated IES loci were detected by DLR-jPCR. (B) WT, TPB2 mut (cross 1: #6 × #38; cross 2: #41 × #44) and PDD1 KO (∆PDD1) strains were mated, and their small RNAs were sequenced. (Top) Normalized numbers (in RPKM) of 26- to 32-nt small RNAs at 3, 10, and 12 hpm that uniquely matched the 3,293 type B IESs are shown as box plots as in Fig. 2D. (Bottom) Normalized numbers (in RPM) of sequenced 26- to 32-nt small RNAs at 10 hpm uniquely mapping to the indicated type B IES loci are shown as histograms with 50-nt bins. Sky-blue boxes indicate IESs. (C) Comparison of the timing of secondary small RNA biogenesis. (Left) In Tetrahymena, primary (1°) small RNAs fully or partially cover IESs and induce heterochromatin formation, which triggers the production of secondary (2°) small RNAs. Secondary small RNAs further induce heterochromatin formation and small RNA production. Eventually, heterochromatinized IESs are excised. (Right) In Paramecium, primary small RNAs cover IESs homogeneously. The excised IESs form concatenated circles, which are transcribed to produce secondary small RNAs. Secondary small RNAs further induce IES elimination and small RNA production.