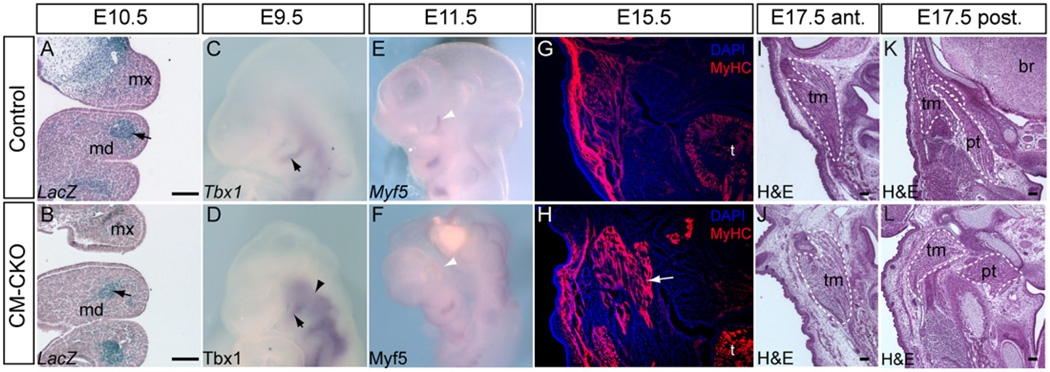

Fig. 4.

Myogenic differentiation of branchiomeric muscles is unaffected by the loss of Twist1 in the cranial mesoderm. (A-B) Mesp1-Cre; Rosa26R cells are located correctly in the first and second branchial arch of E10.5 CM–CKO embryos (black arrow, B), similar to the control (black arrow, A). (C–F) Correct initiation of myogenic differentiation. The mesodermal core in the branchial arches of control and CM–CKO embryos show comparable levels of Tbx1 (black arrow, D) and Myf5 expression (F) in the core tissues of the branchial arches of (C, D) E9.5 and (E, F) E11.5 embryos. The E9.5 CM–CKO embryo shows enhanced Tbx1 expression in the cranial paraxial mesoderm (arrowhead, D). Myf5 is expressed in the peri-ocular region of control but not CM–CKO embryos at E11.5 (white arrowheads, E, F). (G, H) Differentiation of muscle fibers is not affected in CM–CKO embryo at E15.5, revealed by the presence of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) protein in the facial muscles (H, white arrow: extra muscle masses are seen in this section of the mutant embryo, compared to the control (G). (I,J) In this example of the masticator muscles of the E17.5 CM–CKO embryo (J) shows more loosely packed fibers than (I) the control counterpart muscle (section plane: anterior to the otic capsule). Some muscles in the posterior head region are related inappropriately with the surrounding skeletal elements that are also disoriented. Dashed lines mark the corresponding muscles in the control (K) and the CM–CKO (L) embryos); br, brain; md, mandible; mx, maxilla; pt, pterygoid muscle; t, tongue; tm, temporal muscle. Scale bar=100 µm.