Abstract

Background and Purpose:

The clinical utility of PET imaging in evaluating carotid artery plaque vulnerability remains unclear. Two tracers of recent interest for carotid plaque imaging are 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) and 18F-sodium fluoride (18F-NaF). We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the association between carotid artery 18F-FDG or 18F-NaF uptake and recent or future cerebral ischemic events.

Methods:

A systematic review of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and the Cochrane library was conducted from inception to December 2017 for articles evaluating PET tracer uptake in recently symptomatic versus asymptomatic carotid arteries, and articles evaluating carotid uptake in relation to future ischemic events. Cerebral ischemic events were defined as ipsilateral strokes, transient ischemic attacks or amaurosis fugax. We quantitatively pooled studies by a random-effects model when 3 or more studies were amenable for analysis. We assessed the standardized mean difference between tracer uptake in the symptomatic versus asymptomatic carotid artery using Cohen’s d metric.

Results:

After screening 4,144 unique articles, 13 prospective cohort studies assessing carotid artery 18F-FDG uptake in patients with recent cerebral ischemia were eligible for review. Eleven cohorts of 290 subjects scanned with 18F-FDG were eligible for meta-analysis. We found that carotid arteries ipsilateral to recent ischemic events had significantly higher 18F-FDG uptake than asymptomatic arteries (Cohen’s d=0.492, CI=0.130–0.855, P=0.008) as well as significant heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q = 31.5, P = 0.0005; I2 = 68.3%). Meta-regression was not performed due to the limited number of studies in the analysis. Only 2 studies investigating 18F-NaF PET imaging and another 2 articles investigating ischemic event recurrence were found.

Conclusions:

Recent ipsilateral cerebral ischemia may be associated with increased carotid 18F-FDG uptake on PET imaging regardless of degree of carotid stenosis, although significant heterogeneity was found and these results should be interpreted with caution. Emerging evidence suggests a similar association may be present with 18F-NaF plaque uptake. More studies are warranted to provide definitive conclusions on the utility of 18F-FDG or 18F-NaF in carotid plaque evaluation before investigating carotid PET as a diagnostic tool for cerebral ischemic events.

Keywords: Positron-Emission Tomography, Carotid Arteries, Fluorodeoxyglucose F18, Sodium Fluoride F18, Brain Ischemia

Subject terms: Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, Ischemic Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA), Atherosclerosis, Imaging, Nuclear Cardiology and PET, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Carotid artery atherosclerosis is responsible for approximately 10% of first-time ischemic strokes1,2. In the evaluation of symptomatic carotid plaques, information provided by non-invasive imaging techniques can be used for more comprehensive assessment of plaque vulnerability beyond simple luminal stenosis measurements3. By providing insight into tissue metabolism, studies have shown that atherosclerotic plaque uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) on positron emission tomography (PET) is strongly correlated with well-established markers of inflammation such as hypermetabolic CD68 macrophages, cathepsin K, MMP-9 and IL-18 on histology as well as plaque angiogenesis and hypoxia4. The potential value of such imaging tracers in pinpointing recent culprit plaques is suggested by data demonstrating that symptomatic plaques show a gradual decline in macrophage density on histology for up to 180 days after the onset of symptoms5,6. By contrast, 18F-sodium fluoride (18F-NaF) highlights vessel microcalcifications implicated in actively inflamed atherosclerotic lesions7 by binding to hydroxyapatite in vessel walls. Moreover, 18F-NaF uptake has been shown to correlate with generalized atherosclerotic risk factors such as age, hypertension, diabetes, male sex, smoking, hypercholesterolemia and prior cardiovascular events8,9. Thus 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF PET studies have potential to identify active plaques and provide an assessment of plaque biology and, possibly, vulnerability.

Several recent studies have used PET imaging to identify culprit plaques following stroke or transient ischemic attacks and to predict future cerebral ischemic events. However, these studies have generally been small and sometimes shown conflicting results making it difficult to draw definite conclusions on the utility of PET imaging in symptomatic carotid artery evaluation. Given the preliminary level of evidence available in the literature, we did not intend to assess carotid PET as a diagnostic tool for cerebral ischemic events. Rather, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the medical literature for studies that examined carotid plaque PET tracer uptake in relationship to recent prior or future cerebral ischemic events to estimate the effect size of carotid SUV uptake across symptomatic and asymptomatic arteries. We hypothesized that 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF uptake in carotid arteries ipsilateral to a recent ischemic event is higher than uptake in the contralateral artery.

Methods

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files. This study was performed in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group10 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement11.

Data Sources and Searches

An experienced medical librarian performed comprehensive literature searches in the electronic databases Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and The Cochrane Library (Wiley) to identify relevant published studies from database inception through December 5th 2017. There were no language, publication date, or article type restrictions on the search strategy. The full search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE is available in supplement. Subject headings and keywords were then adapted for the other databases. Additional records were identified by employing the “Cited by” and “View references” features in Scopus. The full PRISMA flow diagram outlining the study selection process is available in supplement (Supplemental Figure I).

Study Selection

We included studies evaluating the association of ipsilateral carotid plaque 18F-FDG or 18F-NaF uptake on PET examinations in patients with recent and/or future ischemic events. Specific inclusion criteria were (a) studies of adult subjects (aged >18 years); (b) studies of patients with acute cerebral infarction, transient ischemic stroke (TIA) or retinal embolism/amaurosis fugax; (c) studies of patients who underwent PET scanning within 180 days of an index ischemic cerebral event; (d) studies measuring PET tracer uptake in atherosclerotic lesions within arterial stenosis or plaques in the distal common carotid or proximal internal carotid artery (tracer uptake within plaques or artery walls will be used interchangeably); (e) studies correlating carotid plaque uptake with at least one of the following outcome measures: recent ischemic events, recurrence of ischemic events in patients who were recently symptomatic, future ischemic events in asymptomatic patients; and (f) studies including ≥5 subjects to avoid the inclusion of case reports or very small case series. Patients with infarctions that were likely due to cardiogenic embolic sources or secondary non-atherosclerotic etiologies such as vasculitis, infective endocarditis or reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome were excluded from this study.

We chose to include only peer-reviewed journal articles rather than conference abstracts in order to include studies which provide sufficient detail for systematic review and meta-analysis. Only original studies were considered for inclusion. If data from a single patient cohort was published more than once, the single paper with the largest sample size was included to minimize analysis of duplicate study samples. If necessary, we contacted corresponding authors for clarification during the data extraction process.

Data Extraction

Two investigators independently screened all references produced by the literature search against predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria, then examined the shortlisted articles in full to determine eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or 3rd reviewer. After eligibility was determined, an investigator then extracted data such as sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria, patient demographics and medical treatment, degree of stenosis studied, symptom-to-scan time, and all relevant reported PET tracer uptake metrics.

PET tracer uptake metrics

PET tracer uptake has been reported in a variety of metrics (Supplemental Table I). Standardized uptake values (SUV) are commonly used due to standardization to total body injected activity12. By demarcating regions or volumes of interest (ROI/VOI) around a carotid artery/plaque (Figure 1), maximum SUV (SUVmax) or mean SUV (SUVmean) across all voxels of a section can be calculated. We also collected data on the target/tissue-to-background ratio (TBR) when made available by authors, which is calculated by dividing the SUV of a tissue of interest by that of a venous blood pool.

FIGURE. 1. 18F-FDG PET/MR Image.

showing increased uptake of FDG in a right carotid artery plaque causing less than 50% stenosis (white arrow).

Risk of Bias Assessment

Since PRISMA guidelines on risk of bias assessment are more suited for assessing randomized controlled than cohort studies, we opted to assess the screened articles for risk of bias by adapting a previously published questionnaire13 for bias assessment in the imaging of carotid disease (Supplemental Table II).

Statistical Analysis

Studies that quantitatively reported tracer uptake for symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid arteries were used for meta-analysis. Reported means and standard deviations for symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid arteries in each study were used to calculate Cohen’s effect size (d), which is the standardized mean difference (i.e., mean difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid arteries divided by the pooled standard deviation). It should be noted, however, that a true side-by-side “paired” comparison of SUV values between symptomatic and asymptomatic arteries within the same patient was not possible because the individual studies did not provide the standard deviation of the differences (in SUV) between the symptomatic and asymptomatic arteries (required to compute Cohen’s effect size for paired data). As a result, we assumed independence of the symptomatic and asymptomatic arteries within a patient (i.e., to be conservative) and calculated the effect size as the mean difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic arteries divided by the pooled standard deviation. The individual study effect sizes were then combined into a pooled effect size. In studies where the median and range (or interquartile range) were reported instead of the mean and standard deviation, the median was used instead of the mean and the standard deviation was estimated from the range/interquartile range. Due to the significant variety in reported outcomes, degrees of stenosis studied, scan protocoling and analysis, and symptom-to-scan times, a random-effects (DerSimonian-Laird) model was used to pool the effect sizes when a minimum of 3 or more studies were available to be pooled. Additionally, we performed 5 subgroup analyses in order to adjust for the two most consistently reported patient covariates: degree of stenosis and radiotracer circulating time. Heterogeneity was measured using Cochran’s Q and a p-value ≤ 0.20 was used to indicate the presence of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was also tested using an inconsistency measure (the I2 statistic), and a I2 percentage ≥ 50% was used to indicate the presence of heterogeneity. Publication bias was statistically tested with the Begg–Mazumdar rank-correlation test and Egger’s test. Meta-regression (to further explore sources of heterogeneity between the individual study effect sizes) was not performed due to the small number of studies in the analysis. Meta-analysis was conducted with the use of StatsDirect statistical software (Version 3.1.20) (7/18/2018 StatsDirect Ltd, Cheshire, England).

Results

A total of 4,144 abstracts were screened, of which 30 studies potentially met our inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 13 studies14–26 were found to be eligible for review (Table 1). One study27 was found to meet the inclusion criteria but was not included in analysis due to an overlap in sample size with a more recent and larger study20.

TABLE 1.

Overview of Included Studies

| First Author and Year | PET Tracer | Number of Subjects | Mean Age | % Males | Ischemic Events included | Patient Medical Therapy at enrollment | Stenosis % studied | Symptom-to-scan time range (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statins | Anti-hypertensives | Anti-platelets | |||||||||

| 1 | Rudd 200214 | 18F-FDG | 8 | 63.5 | 75 (6/8) | TIA | N/A | N/A | N/A | 70–99% | 105† |

| 2 | Davies 200515 | 18F-FDG | 12 | 71 | 83.3 (10/12) | TIA | All | Some | All | 65–99% | 64±43‡ |

| 3 | Graebe 201016 | 18F-FDG | 33 | 68 | 75.8 (25/33) | Stroke/TIA/amaurosis fugax | All | N/A | All | Any% | <90 |

| 4 | Moustafa 201017 | 18F-FDG | 16 | 70.5 | 87.5 (14/16) | Minor stroke/TIA/amaurosis fugax | 14/16* | 7/16* | All* | 50–99% | <90 |

| 5 | Kwee 201118 | 18F-FDG | 50 | 67.8 | N/A | non-debilitating stroke/TIA | 45/50 | N/A | N/A | <70% | 9–95 |

| 6 | Saito 201319 | 18F-FDG | 25 | 68 | 88 (22/25) | Stroke/TIA/amaurosis fugax | N/A | N/A | N/A | >70% | <180 |

| 7 | Chroinin 201420 | 18F-FDG | 61 | 71.4 | 72.1 (44/61) | Stroke (≤3 Rankin score)/TIA/amaurosis fugax | 54/61* | N/A | 51/61* | 50–99% | <7 |

| 8 | Kim 201421 | 18F-FDG | 21 | 66.3 | 85.7 (18/21) | Stroke | Some* | N/A | All* | Any% | 5.8 (4.3–17.9)† |

| 9 | Shaikh 201422 | 18F-FDG | 29 | 67.1 | 75.9 (22/29) | Stroke/TIA/amaurosis fugax | All | 12/29 | All | 50–100% | 21–35 |

| 10 | Skagen 201523 | 18F-FDG | 36 | 67.9 | 72.2 (26/36) | Minor stroke/TIA/amaurosis fugax | 27/36 | 22/36 | N/A | 70–99% | <30 |

| 11 | Hyafil 201624 | 18F-FDG | 18 | 70 | 37 (NA) | Cryptogenic stroke | 6/18 | N/A | 7/18 | <50% | <7 |

| 12 | Quirce 201625 | 18F-FDG, 18F-NaF | 9 | N/A | 88.9 (8/9) | Stroke/TIA | Yes* | N/A | N/A | Any% | <10 |

| 13 | Vesey 201726 | 18F-FDG, 18F-NaF | 18 | 71.7 | 61.5 (11/18) | Minor stroke/TIA | 17/18 | Many | 17/18 | >50% males, >70% females | N/A |

FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; NaF, sodium fluoride; N/A, data not available.

At the time of PET scan as opposed to time of enrollment,

median and interquartile ration,

mean and standard deviation

Qualitative Assessment and Study Characteristics

All 13 selected articles were prospective cohort studies. Five studies were conducted in the United Kingdom14,15,17,22,26, and 1 each in Ireland20, Denmark16, Germany24, Japan19, Republic of Korea21, the Netherlands18, Norway23 and Spain25. A wide range of carotid stenosis severity was studied amongst the reviewed literature with 3 studies investigating arteries regardless of degree of stenosis16,21,25, 3 studies including patients with ≥50% stenosis17,20,22, and 3 including patients with ≥70% stenosis14,19,23. Four studies examined a mixture of nonstenotic and stenotic arteries15,18,24,26.

The mean age of patients across the included articles was similar and ranged from 63.5 to 71.7. All but one study15 had a preponderance of males with percentage males ranging from 37% to 88.9%, with an average of 73.9% males across all studies. Symptom-to-scan time varied between 3 days and 6 months across the studies. One study scanned patients awaiting carotid endarterectomy but did not specify a timeline or symptom-to-scan time26. Tracer dosing and scan protocols varied widely amongst the included articles (Supplemental Table III). All but two studies18,26 reported a single metric of interest. For the studies that included two metrics, we collected data on max TBRmax rather than TBRmean in one article18, and mean SUVmax in another26 in line with the most common metrics in our meta-analysis (Supplemental Table I).

Amongst the 13 included articles, 2 investigated carotid 18F-FDG uptake in relation to recurrence20,21, and another 2 also analyzed carotid 18F-NaF uptake25,26. The patient characteristics of these cohorts did not differ considerably from the main 18F-FDG cohort but because only 2 cohorts were found in each group, quantitative analysis was not carried out. With regards to 18F-NaF cohort, these two articles investigated a total of 27 subjects with 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF. Quirce et al.25 showed that carotid 18F-NaF uptake was overall higher in symptomatic plaques (2.12±0.44 vs 1.85±0.46) but the results did not reach significance amongst the either 18F-FDG or 18F-NaF cohorts due to the relatively small sample size (n=9). Vesey et al.26 on the other hand found a significantly higher 18F-NaF uptake in symptomatic carotid plaques than contralateral plaques (2.42, IQR=2.24–3.24 vs. 1.97, IQR =1.78–2.74), but did not find the same with 18F-FDG.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Our risk of bias questionnaire (Supplemental Table II) revealed that all 13 studies reported their inclusion criteria clearly, but two did not specify exclusion criteria19,22. Eight of the 13 included studies evaluated carotid plaque uptake in relation to recent or future ischemic events as their primary objective14,15,18,19,23,24,26. Given the semi-quantitative nature of uptake measurement, some studies showed risk of outcome ascertainment bias. Only 7 studies described some form of blinding to patient characteristics or stroke laterality in the image analysis process15,18,20,21,23,24,26. Furthermore, only 2 studies carried out inter-rater reliability analysis24,26. Four studies provided individual patient uptake data14,15,17,25. Six studies in total collected potentially confounding factors16,20,21,23,24,26. Loss to follow-up was not reported explicitly in the a majority of the included studies with the exception of 2 articles, of which one reported complete follow-up20 and another reported a loss of 3 patients in the 18F-FDG and 4 in the 18F-NaF arms of the study26.

Meta-analysis Results

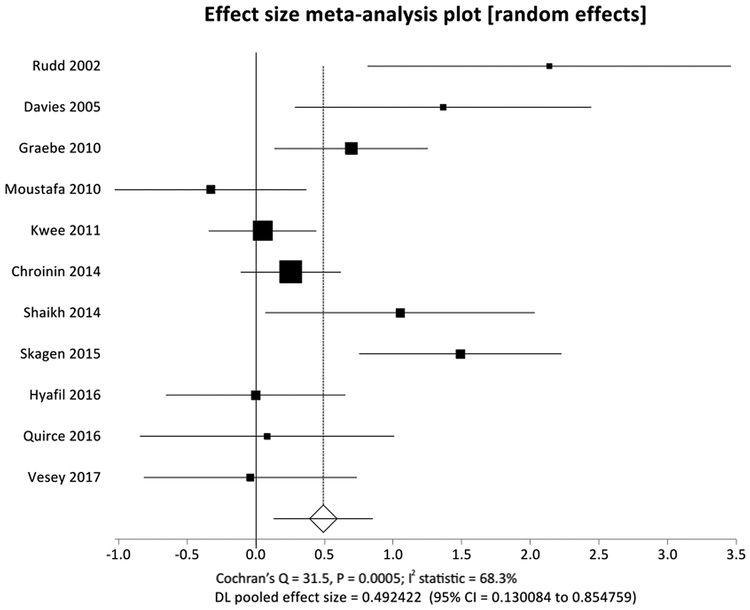

Eleven of the 13 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were amenable for 18F-FDG meta-analysis14–20,22–26. Two studies were not included because one study19 reported uptake as either positive or negative based on a predefined threshold, and another21 study did not provide asymptomatic artery uptake for comparison. A total of 290 subjects were analyzed for 266 symptomatic and 220 asymptomatic arteries using a random-effects model (Table 2 and Figure 2). Because three studies19,21,23 compared plaques from symptomatic patients to plaques from asymptomatic controls, carotid artery uptake values from all studies were conservatively analyzed as independent even when they originated from the same subject. We found that carotid 18F-FDG uptake was significantly higher in recently symptomatic carotid arteries than asymptomatic ones (Cohen’s d = 0.492, CI = 0.130 – 0.855, P = 0.008). When a fixed-effects model was used, the results were similar. We found no significant publication bias (Kendall’s tau [Begg-Mazumdar test] = 0.454, P = 0.0602; Egger’s bias = 2.32, P = 0.103) but found significant heterogeneity amongst the analyzed literature (Cochran’s Q = 31.5, P = 0.0005; I2 = 68.3%) (Supplemental Figure II and Table IV).

TABLE 2.

18F-FDG Studies Results

| First Author and Year | Number of Subjects | Selected Metric of Interest | Symptomatic Arteries (N) | Mean Symptomatic Value (SD) | Asymptomatic Arteries (N) | Mean Asymptomatic Value (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rudd 200214 | 8 | Net FDG accumulation rate | 8 | 7.95 (0.58) | 6 | 6.21 (0.96) |

| 2 | Davies 200515 | 12 | Plaque-to-normal artery uptake ratio | 12 | 1.705 (0.44) | 6 | 1.145 (0.25) |

| 3 | Graebe 201016 | 33 | Mean SUVmax† | 34 | 2.086 (1.76–2.78) | 21 | 1.847 (1.65–2.13) |

| 4 | Moustafa 201017 | 16 | PV-corrected SUVmean | 16 | 3.723 (0.97) | 16 | 4.257 (2.03) |

| 5 | Kwee 201118 | 50 | Max TBRmax* | 50 | 1.46 (0.05) | 50 | 1.44 (0.06) |

| 7 | Chroinin 201420 | 61 | Mean SUVmax | 61 | 2.483 (0.616) | 56 | 2.341 (0.478) |

| 9 | Shaikh 201422 | 29 | Patlak maximum dynamic FDG uptake‡ | 29 | 9.7 (7.1–12.2) | 5 | 8.6 (6.8–11.9) |

| 10 | Skagen 201523 | 36 | Mean SUVmax‡ | 18 | 1.75 (1.26–2.04) | 18 | 1.43 (1.15–2.38) |

| 11 | Hyafil 201624 | 18 | Mean SUVmax | 18 | 2.5 (0.6) | 18 | 2.5 (0.8) |

| 12 | Quirce 201625 | 9 | Max TBRmax | 9 | 1.85 (0.37) | 9 | 1.81 (0.53) |

| 13 | Vesey 201726 | 18 | Mean SUVmax | 11 | 2.21 (0.72) | 15 | 2.24 (0.74) |

| Total | 290 | 266 | Total | 220 |

FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; SUV, standardized uptake value; TBR, target-to-background ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Standard error reported,

median and inter-quartile range reported,

median and range reported

FIGURE. 2. Effect size forest plot.

illustrates the association between carotid 18F-FDG uptake and recent ipsilateral ischemic events. Meta-analysis was carried out using a random-effects model. Squares represent point estimates of effect size (Cohen’s d). The size of the squares is proportional to the inverse of the variance of the estimate. The diamond represents the pooled estimate and horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence interval of each study.

When subgroup analysis was carried out (Supplemental Figures III–VII), we found that 18F-FDG uptake remained significantly higher in ipsilateral carotid arteries of patients with >70% stenosis (Cohen’s d = 1.645, CI = 1.000 – 2.289, P < 0.0001) and >50% stenosis (Cohen’s d = 0.737, CI = 0.143 – 1.331, P = 0.0151). Our results were not significant when we pooled studies of <70% stenosis (P = 0.894). Only one study investigated <50% stenosis, and so no analysis on this subgroup could be carried out. Analyzing studies that utilized 2 or more hours of circulating time approached significance (P = 0.06), and so did studies that used less than 2 hours of circulating time (P = 0.09).

Ischemic Event Recurrence Studies

Only 2 studies assessed recurrence of ischemic events after measurement of 18F-FDG plaque uptake20,21. No studies investigating first time cerebral ischemic events in relation to baseline asymptomatic carotid artery tracer uptake were found. Chroinin et al.20 followed a cohort of 61 subjects with no loss to follow-up for 90 days after the index event, finding that 18F-FDG uptake was associated with 90-day recurrence (odds ratio per unit increase in max SUVmax of 5.76, CI=1.48–22.39, p=0.01 after adjustment). Kim et al.21 also assessed recurrence using a series of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) scans a median of 6.4 days apart after an ischemic event in 21 patients and found that those with early recurrent ischemic lesions on repeat DWI had a significantly higher ipsilateral uptake than those that did not (3.07±0.79 vs. 2.17±0.68, p=0.013).

Discussion

In the assessment of carotid artery plaques, stenosis severity measurements play an important role in management and treatment guidelines28–30. However, emerging evidence suggests that non-invasive modalities can characterize and assess carotid atherosclerotic lesion vulnerability31. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that patients who suffered recent cerebral ischemic events had significantly higher 18F-FDG uptake in the ipsilateral carotid artery. We also found early evidence suggesting that 18F-NaF may similarly identify symptomatic plaques but that further studies are needed to arrive at more definitive conclusions about the role of 18F-NaF in characterizing carotid plaque.

We also found some important limitations of the existing body of PET literature of symptomatic carotid disease. Firstly, we noted considerable inconsistency in study methods and outcome reporting (Supplemental Table V), which likely contributed heavily to the heterogeneity found in our results. Unfortunately, due to the small number of studies in the meta-analysis overall, conducting a formal meta-regression to statistically evaluate potential study-level factors that could contribute to the observed heterogeneity in the individual study effects sizes was not possible. Specifically, with only 11 studies in total in the 18F-FDG meta-analysis, and with a small number of all 13 studies falling into categorical levels of study-level covariates of interest (e.g., degree of stenosis, scan protocolling and analysis, etc.), conducting a formal meta-regression analysis would be grossly underpowered for detecting significant heterogeneity related to the potential study-level covariates of interest. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution. Future studies may benefit from a more standardized approach as suggested by several studies32–34 such as allowing for at least 2 hours of tracer circulating time, injecting an adequate dose of 18F-FDG to measure uptake in atherosclerosis, and avoiding scanning patients with blood glucose levels above a certain threshold. Additionally, due to considerable overlap between the symptomatic and asymptomatic uptake values as well as the technical variability of PET scans, definitions of threshold values for clinical use have proven difficult to establish. Our literature review revealed some uptake thresholds defined based on histological analysis of inflammation35, and others based on uptake in healthy subjects36,37. Furthermore, this review highlights the lack of consensus on uptake reporting despite an evident trend towards using TBR for carotid plaque imaging given evidence suggesting that TBR correlates better with inflammation on histology than SUV38. Nevertheless, we recommend that studies report all available metrics to allow systematic analysis and validation of these metrics.

Another limitation of the existing literature, especially in the case of 18F-FDG, is the failure to account for several patient variables including patient risk factors and comorbidities, and patient medical therapy prior to scanning. Because these variables were not routinely reported in the literature, they could not be fully accounted for in our analysis. For example, several studies39,40 have found that statin therapy lowers plaque 18F-FDG uptake, with one study noting a significant reduction in arterial inflammation within 4 weeks41. As such, we were limited in our ability to determine the magnitude for any effect modification statins, for example, may have had on our results. Similarly, no literature was found describing the impact statins on 18F-NaF uptake.

Though our study shows that the role of 18F-FDG as a marker of arterial inflammation has been relatively well-studied, understanding of the mechanism of 18F-NaF uptake in carotid plaques is based on relatively recent experimental data. 18F-NaF, commonly used in clinical practice to identify bone metastases, binds to hydroxyapatite in vascular calcifications, and is able to detect microcalcifications below the resolution of CT42. Such microcalcifications have been hypothesized to be a significant contributor to plaque instability43 given cellular data suggesting that the earliest stages of atherosclerotic vascular microcalcification is a direct response to an intense inflammatory stimulus44. Furthermore, studies suggest that while macroscopic calcium deposits in plaques confer additional mechanical stability, microcalcifications can significantly increase mechanical stress in the fibrous cap45. In fact, 18F-NaF uptake has been reported to highlight calcifications in a distribution that does not always overlap with macrocalcifications as seen on CT46, without significant regional overlap between macrocalcifications and 18F-NaF uptake8. These pathophysiologic insights suggest that 18F-NaF may be similarly effective to 18F-FDG in identifying in culprit plaques, though investigations in larger studies are required to confirm this hypothesis. More studies comparing 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF uptake distributions may shed light on each tracer’s clinical utility, reflecting the different pathophysiological processes they proxy.

Given that our quantitative analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity, our study suggests that definitive conclusions regarding the differences of 18F-FDG uptake in symptomatic versus asymptomatic plaques will require that future studies consider more standardized methodology in terms of image acquisition techniques, image analysis and outcome reporting. At present, though the evidence is insufficient to generalize the significant results of this meta-analysis to all stroke patients or for the use of PET imaging as a routine diagnostic tool in such patients, directed future research efforts are needed to allow for better validation and interpretation of test results. Despite the current limitations in the literature, our systematic review and meta-analysis may suggest a promising role for PET imaging in non-invasive interrogation of atherosclerosis, as part of a multimodal diagnostic risk stratification strategy in patients suffering cerebral ischemia likely due to carotid atherosclerosis. In addition to valuable diagnostic information provided by MRI or CT13,47, PET may help identify active atherosclerotic lesions, especially in the case of several suspect plaques or non-stenotic atherosclerosis, for medical or targeted surgical therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We sincerely thank Dr. Fabien Hyafil24 and Dr. Danielle Ní Chróinín20 for providing information related to their studies.

Sources of Funding:

Dr. Paul Christos was partially supported by the following grant: Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College (1-UL1-TR002384–01).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None.

References:

- 1.Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, Zamanillo MC. Race-ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke. 1995;26(1):14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wityk RJ, Lehman D, Klag M, Coresh J, Ahn H, Litt B. Race and sex differences in the distribution of cerebral atherosclerosis. Stroke. 1996;27(11):1974–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalela JA. Evaluating the carotid plaque: going beyond stenosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27 Suppl 1:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedersen SF, Hag AM, Klausen TL, Ripa RS, Bodholdt RP, Kjaer A. Positron emission tomography of the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque in man--a contemporary review. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014;34(6):413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peeters W, Hellings WE, de Kleijn DP, de Vries JP, Moll FL, Vink A, et al. Carotid atherosclerotic plaques stabilize after stroke: insights into the natural process of atherosclerotic plaque stabilization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(1):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redgrave JN, Lovett JK, Gallagher PJ, Rothwell PM. Histological assessment of 526 symptomatic carotid plaques in relation to the nature and timing of ischemic symptoms: the Oxford plaque study. Circulation. 2006;113(19):2320–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKenney-Drake ML, Moghbel MC, Paydary K, Alloosh M, Houshmand S, Moe S, et al. (18)F-NaF and (18)F-FDG as molecular probes in the evaluation of atherosclerosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(12):2190–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morbelli S, Fiz F, Piccardo A, Picori L, Massollo M, Pestarino E, et al. Divergent determinants of 18F-NaF uptake and visible calcium deposition in large arteries: relationship with Framingham risk score. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30(2):439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derlin T, Wisotzki C, Richter U, Apostolova I, Bannas P, Weber C, et al. In vivo imaging of mineral deposition in carotid plaque using 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT: correlation with atherogenic risk factors. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(3):362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams MC, Turkington TG, Wilson JM, Wong TZ. A systematic review of the factors affecting accuracy of SUV measurements. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(2):310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baradaran H, Al-Dasuqi K, Knight-Greenfield A, Giambrone A, Delgado D, Ebani EJ, et al. Association between Carotid Plaque Features on CTA and Cerebrovascular Ischemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(12):2321–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudd JH, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, Jones HA, Clark JC, Antoun N, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105(23):2708–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies JR, Rudd JH, Fryer TD, Graves MJ, Clark JC, Kirkpatrick PJ, et al. Identification of culprit lesions after transient ischemic attack by combined 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography and high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2642–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graebe M, Pedersen SF, Hojgaard L, Kjaer A, Sillesen H. 18FDG PET and ultrasound echolucency in carotid artery plaques. Jacc: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2010;3(3):289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moustafa RR, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Fryer TD, Graves MJ, Rudd JH, Gillard JH, et al. Carotid plaque inflammation is associated with cerebral microembolism in patients with recent transient ischemic attack or stroke: a pilot study. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2010;3(5):536–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwee RM, Truijman MT, Mess WH, Teule GJ, ter Berg JW, Franke CL, et al. Potential of integrated [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/CT in identifying vulnerable carotid plaques. Ajnr: American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2011;32(5):950–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito H, Kuroda S, Hirata K, Magota K, Shiga T, Tamaki N, et al. Validity of dual MRI and F-FDG PET imaging in predicting vulnerable and inflamed carotid plaque. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013;35(4):370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chroinin DN, Marnane M, Akijian L, Merwick A, Fallon E, Horgan G, et al. Serum lipids associated with inflammation-related PET-FDG uptake in symptomatic carotid plaque. Neurology. 2014;82(19):1693–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HJ, Oh M, Moon DH, Yu KH, Kwon SU, Kim JS, et al. Carotid inflammation on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography associates with recurrent ischemic lesions. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2014;347(1–2):242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaikh S, Welch A, Ramalingam SL, Murray A, Wilson HM, McKiddie F, et al. Comparison of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in symptomatic carotid artery and stable femoral artery plaques. British Journal of Surgery. 2014;101(4):363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skagen K, Johnsrud K, Evensen K, Scott H, Krohg-Sorensen K, Reier-Nilsen F, et al. Carotid plaque inflammation assessed with (18)F-FDG PET/CT is higher in symptomatic compared with asymptomatic patients. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(5):730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyafil F, Schindler A, Sepp D, Obenhuber T, Bayer-Karpinska A, Boeckh-Behrens T, et al. High-risk plaque features can be detected in non-stenotic carotid plaques of patients with ischaemic stroke classified as cryptogenic using combined (18)F-FDG PET/MR imaging. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine & Molecular Imaging. 2016;43(2):270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quirce R, Martinez-Rodriguez I, Banzo I, Jimenez-Bonilla J, Martinez-Amador N, Ibanez-Bravo S, et al. New insight of functional molecular imaging into the atheroma biology: 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG in symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid plaques after recent CVA. Preliminary results. Clinical Physiology & Functional Imaging. 2016;36(6):499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vesey AT, Jenkins WS, Irkle A, Moss A, Sng G, Forsythe RO, et al. 18F-Fluoride and 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography After Transient Ischemic Attack or Minor Ischemic Stroke: Case-Control Study. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2017;10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marnane M, Merwick A, Sheehan OC, Hannon N, Foran P, Grant T, et al. Carotid plaque inflammation on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts early stroke recurrence. Annals of Neurology. 2012;71(5):709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet (London, England). 1998;351(9113):1379–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial C, Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Peerless SJ, et al. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1415–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brinjikji W, Huston J, 3rd, Rabinstein AA, Kim GM, Lerman A, Lanzino G. Contemporary carotid imaging: from degree of stenosis to plaque vulnerability. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(1):27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blomberg BA, Akers SR, Saboury B, Mehta NN, Cheng G, Torigian DA, et al. Delayed time-point 18F-FDG PET CT imaging enhances assessment of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Nucl Med Commun. 2013;34(9):860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bucerius J, Mani V, Moncrieff C, Machac J, Fuster V, Farkouh ME, et al. Optimizing (18)F-FDG PET/CT Imaging of Vessel Wall Inflammation–The Impact of (18)F-FDG Circulation Time, Injected Dose, Uptake Parameters, and Fasting Blood Glucose Levels. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(2):369–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huet P, Burg S, Le Guludec D, Hyafil F, Buvat I. Variability and uncertainty of 18F-FDG PET imaging protocols for assessing inflammation in atherosclerosis: suggestions for improvement. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(4):552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Bashian GG, Bedri S, Vermylen D, Cury RC, et al. In vivo 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(9):1818–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu YW, Kao HL, Chen MF, Lee BC, Tseng WY, Jeng JS, et al. Characterization of plaques using 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with carotid atherosclerosis and correlation with matrix metalloproteinase-1. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(2):227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Valk FM, Verweij SL, Zwinderman KA, Strang AC, Kaiser Y, Marquering HA, et al. Thresholds for Arterial Wall Inflammation Quantified by (18)F-FDG PET Imaging: Implications for Vascular Interventional Studies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(10):1198–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niccoli Asabella A, Ciccone MM, Cortese F, Scicchitano P, Gesualdo M, Zito A, et al. Higher reliability of 18F-FDG target background ratio compared to standardized uptake value in vulnerable carotid plaque detection: a pilot study. Ann Nucl Med. 2014;28(6):571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emami H, Vucic E, Subramanian S, Abdelbaky A, Fayad ZA, Du S, et al. The effect of BMS-582949, a P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (P38 MAPK) inhibitor on arterial inflammation: a multicenter FDG-PET trial. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240(2):490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tahara N, Kai H, Ishibashi M, Nakaura H, Kaida H, Baba K, et al. Simvastatin attenuates plaque inflammation: evaluation by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(9):1825–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tawakol A, Fayad ZA, Mogg R, Alon A, Klimas MT, Dansky H, et al. Intensification of statin therapy results in a rapid reduction in atherosclerotic inflammation: results of a multicenter fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography feasibility study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(10):909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tawakol A, Osborne MT, Fayad ZA. Molecular Imaging of Atheroma: Deciphering How and When to Use (18)F-Sodium Fluoride and (18)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maldonado N, Kelly-Arnold A, Vengrenyuk Y, Laudier D, Fallon JT, Virmani R, et al. A mechanistic analysis of the role of microcalcifications in atherosclerotic plaque stability: potential implications for plaque rupture. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(5):H619–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joshi NV, Vesey AT, Williams MC, Shah AS, Calvert PA, Craighead FH, et al. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):705–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vengrenyuk Y, Carlier S, Xanthos S, Cardoso L, Ganatos P, Virmani R, et al. A hypothesis for vulnerable plaque rupture due to stress-induced debonding around cellular microcalcifications in thin fibrous caps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(40):14678–14683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derlin T, Richter U, Bannas P, Begemann P, Buchert R, Mester J, et al. Feasibility of 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT for imaging of atherosclerotic plaque. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(6):862–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gupta A, Baradaran H, Schweitzer AD, Kamel H, Pandya A, Delgado D, et al. Carotid plaque MRI and stroke risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3071–3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.