Abstract

Health education research emphasizes the importance of cultural understanding and fit to achieve meaningful psycho-social research outcomes, community responsiveness and external validity to enhance health equity. However, many interventions address cultural fit through cultural competence and sensitivity approaches that are often superficial. The purpose of this study was to better situate culture within health education by operationalizing and testing new measures of the deeply grounded culture-centered approach (CCA) within the context of community-based participatory research (CBPR). A nation-wide mixed method sample of 200 CBPR partnerships included a survey questionnaire and in-depth case studies. The questionnaire enabled the development of a CCA scale using concepts of community voice/agency, reflexivity and structural transformation. Higher-order confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated factorial validity of the scale. Correlations supported convergent validity with positive associations between the CCA and partnership processes and capacity and health outcomes. Qualitative data from two CBPR case studies provided complementary socio-cultural historic background and cultural knowledge, grounding health education interventions and research design in specific contexts and communities. The CCA scale and case study analysis demonstrate key tools that community–academic research partnerships can use to assess deeper levels of culture centeredness for health education research.

Introduction

With vast and growing health and social inequities in poor and ethnic/racial communities, it is increasingly important that research meets the needs of populations through a deeper understanding of culture [1, 2]. Despite the recognized importance of culture, predominant approaches to health research provide limited understanding of the concept [3, 4]. Culturally adapted, culturally sensitive or culturally competent translations of evidence-based programs often represent ‘surface’ structures of culture, such as tailoring interventions with specific foods or images, whereas ‘deep’ structures seek to represent community values, worldviews, social–environmental structures and social forces [5]. Similarly, health education research has often failed to impact multicultural/vulnerable populations because of its primary focus on individual behavioral goals and evidence-based strategies that have little connection to diverse communities [6, 7].

A recent federal consensus report called for health research to recognize culture as a ‘multi-dimensional bio-psychosocial, ecology’ which contextualizes disparities within diverse populations’ historical and socio-political realities [3, p. 12]. Culture is: ‘an internalized and shared framework used by group (or subgroup) members….This framework is created by, exists in, and adapts to the cognitive, emotional and material resources and constraints of the group’s ecologic system to ensure the survival and well-being of its members, and to provide individual and communal meaning for and in life’ [4, p. 242]. Kagawa-Singer et al. [4] note culture is a multi-level process that requires constant understandings of relationships within social networks and power structures. Health education scholars Airhihenbuwa and Liburd reflect a similar view, with culture a collective consciousness expressed through language and history, yet, especially for marginalized populations, having to respond dynamically to mainstream and often oppressive socio-political structures [8].

Despite this call for deeper, dynamic understanding, there is limited research applying culture in health intervention research. An important exception is the culture-centered approach (CCA) [9]. The CCA theorizes the nexus of culture, structure and agency within collaboratively developed health interventions among academic and community researchers [10]. Similarly to Kagawa-Singer and Airhihenbuwa, Dutta (2007) sees culture as a complex web of communicative meanings as they interact with structural processes [9]. CCA emphasizes human agency and community power as primary cultural strategies to confront social determinants of health [11]. Human agency means community members defining their own etiology of health problems and posing their solutions, which can facilitate equitable power relations within academic-community participatory research.

Although the CCA creates deep culturally grounded health interventions for multicultural and vulnerable populations [12, 13], there have been no efforts previously to develop a scale of CCA or illustrate its meaning across multiple participatory research projects. A scale can help research partnerships self-assess intervention development processes and engage in reflexive practices [9]. Further, the application to various participatory projects demonstrates relevance of the CCA constructs across settings.

This study adds to the literature on better situating culture within health education research to reduce health inequities. We operationalize new measures of the CCA within community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR is a collaborative approach among community–academic partnerships that embraces a socio-ecologic framework, starting from cultural strengths of community members [1, 14]. While participatory research literature is a well-established multidisciplinary approach, including within health education, and uses many terms [15–17], we use CBPR as the most common in public health. CBPR interventions have been shown to improve health and health equity [1, 18, 19].

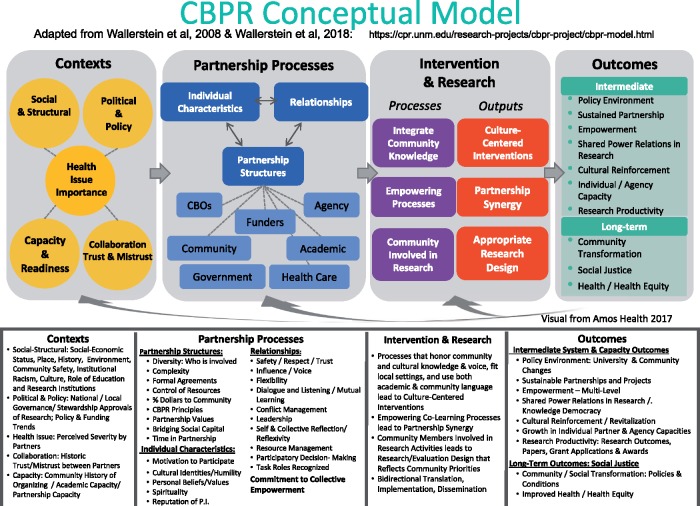

This study reports on a mixed-method, National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded study of diverse community–academic research partnerships in which we systematically assessed culture-centered partnering processes and outcomes from internet surveys and in-depth case studies [20, 21]. This study utilized a CBPR conceptual model, whose four domains illustrate theoretical pathways contributing to outcomes [21, 22]. The model starts with context (consistent with culture as ‘deep structure’), which provides the historic grounding for partnership processes. These processes in turn impact intervention and research design (including community member involvement in research), and ultimately contribute to multiple research, capacity and health outcomes. (See Fig. 1, CBPR model, https://engageforequity.org/cbpr-model/full-model/.) The model was developed over a decade of NIH-funded CBPR empirical research in consultation with CBPR community members, practitioners and academics [1]. In community consultations on the model, culture was named within all domains [23]. We start by introducing the CCA and three key elements that we sought to conceptualize.

Fig. 1.

CBPR conceptual model.

Background to culture-centered approach

The CCA analyses communicative processes that (re)produce marginalization of disenfranchised populations, and challenges this disenfranchisement through validation of community knowledge [9]. Drawing upon postcolonial [24] and subaltern studies [25], CCA theorizes that domination produces communicative erasures that limit opportunities for participation, representation and recognition [10]. Academic–community partnerships become important sites of co-constructed meaning making, with community knowledge honored [26]. Community members can negotiate with and seek local health solutions that transform their socio-political conditions [12, 13, 27]. Three concepts underlie the CCA [9, 10]: community voice/agency, reflexivity and structural transformation and resources.

Community voice/agency

CCA supports communicative processes within academic–community partnerships that foster locally rooted meanings of problem etiologies and solutions and recognize heterogeneity of community interpretations rather than top-down solutions [12, 13, 28]. Key elements of voice/agency are participation and listening to community wisdom and knowledge [10]. Inherent in listening is the shifting of the researchers’ stance toward the community as co-creators/owners of the research, recognizing local knowledge as central. Indigenous communities have been at the forefront of demanding cultural integrity and agency in integrating their knowledge and values, even within adaptations of evidence-based interventions [7, 29].

While Dutta [9] has theorized ‘voice’ and ‘listening’ as communicative metaphors for recognition, the metaphor of voice takes for granted communicative acts (speaking/listening) as transformative, which can be experienced by Deaf communities (one of the case studies here) as unintended reminders of power/oppression. We therefore incorporate ‘agency’ to act, within our use of voice. Academics writing about indigenous oral traditions might also be seen as creating erasure and oppression [1]. These examples reinforce the need for continual reflexivity about often-unintended replays of dominant forms of knowledge production.

Reflexivity

CCA hinges on reflexivity, questioning the taken-for-granted positions of power of researchers in communities [10, 30]. Reflexivity turns the gaze on researchers, continually questioning their privilege in what knowledge is listened to, including in research decision-making, even as they seek to undo these privileges. Reflexivity, through note taking and dialogue within the research team, [17] is integral to co-learning, and can disrupt dominant knowledge claims.

Structural transformation and resources

CCA posits the importance of having resources and changing structures contributing to health problems and inequities [9]. CCA also identifies the role of structures that organize, enable and constrain access to resources when implementing interventions [12]. Reflexivity on structures, however, can open possibilities of transformation when marginalized communities interpret meaning and participate in change [12, 31]. Community capacities for transformation and garnering power can be enhanced within the partnership (e.g. through researchers sharing funds with communities) [1, 32]. Communication resources of participatory mapping [33] and advocacy, such as performances, photo/video voice and strategic media offer spaces for social transformation, including leverage with external stakeholders to secure other resources [34].

Methods

Quantitative methods

Research design and sampling

The quantitative research design implemented two sequential cross-sectional internet surveys: (i) for principal investigators (PIs) to describe facts of the project (key informant survey); and (ii) for PIs and one academic and up to three community partners to describe their experiences and perceived outcomes of the project (community engagement survey [CES]). While details of the design and sample are found elsewhere [35, 36], this study reports on the CES taken by 138 PIs (69% of invited PIs) and 312 partners (77.2% of invited partners). The sample included: (i) 118 academic, 194 community partners; (ii) 272 White, non-Hispanic, 37 American Indian/Alaska Native, 37 African American, 32 Hispanic, 28 Asian/Pacific Islander, 23 mixed race/other and (iii) 205 female, 73 male. The responses for PIs and partners were combined because there was high agreement among the participants about the scales ranging from 0.75 to 0.88 on a measure of consensus [37].

Measures

We created and validated subscales for a new scale of the CCA. There were a total of 22 subscales in the CES derived to measure elements of the CBPR model that were validated (factorial and construct validity) previously [38]. During the planning of the CES, we worked with CCA theory to ensure that we selected or created subscales that reflected the core constructs. Working with the original theorist, along with oversight by a community and academic advisory board, we examined the content of the CCA constructs and ensured that the chosen subscales linked theoretically with these constructs and had face validity (see Table I for specific items and subscales).

Table I.

Individual items and factor loadings of CCA scale

| CCA construct (second order) | M (SD) | Subscale (link to CCA) | Second-order factor loading | Item | Cronbach’s α of subscale | First-order factor loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voice/agency | 2.21 (0.51) 3-point scale | Community member involvement in research—background research (i.e. problem definition) | 0.90 | 6a. Community partners involved with developing community-based theories of the problem or intervention | 0.81 | 0.57 |

| 6b. Community partners involved with grant proposal writing | 0.72 | |||||

| 6c. Community partners involved with background research | 0.68 | |||||

| 6d. Community partners involved with choosing research methods | 0.79 | |||||

| 6e. Community partners involved with developing sampling procedures | 0.65 | |||||

| Community member involvement in research—analysis and dissemination (i.e. solution) | 0.86 | 6k. Community partners involved with interpreting study findings | 0.82 | 0.73 | ||

| 6l. Community partners involved with writing reports and journal articles | 0.85 | |||||

| 6m. Community partners involved with giving presentations at meetings and conferences | 0.74 | |||||

| Community member involvement in research—data collection (i.e. solution) | 0.91 | 6f. Community partners involved with recruiting study participants | 0.69 | 0.53 | ||

| 6g. Community partners involved with implementing the intervention | 0.44 | |||||

| 6h. Community partners involved with designing interview and/or survey questions | 0.75 | |||||

| 6i. Community partners involved with collecting primary data | 0.62 | |||||

| Reflexivity | 4.10 (0.52) 5-point scale | Change in power relations (i.e. reflexivity) | 0.91 | 28a. Community members have increased participation in the research process | 0.81 | 0.77 |

| 28b. Community members can talk about the project in other settings such as a community or political meeting | 0.76 | |||||

| 28c. Community members can apply the findings of the research | 0.66 | |||||

| 28d. Community members can voice their opinions about research in front of researchers | 0.70 | |||||

| 28e. Community members have sought continuing formal or informal education | 0.57 | |||||

| Participatory decision-making (i.e. reflexivity) | 0.62 | 11a. Feel comfortable with the way decisions are made in the project | 0.83 | 0.79 | ||

| 11b. Support the decisions made by the project team members | 0.80 | |||||

| 11c. Feel that your opinion is taken into consideration by other project team members | 0.79 | |||||

| 11d. Feel that you have been left out of the decision-making process (reverse) | 0.62 | |||||

| Transformation | 3.64 (0.63) 5-point scale | Community transformation (i.e. structural transformation) | 0.50 | 25c. Resulted in policy changes | 0.87 | 0.66 |

| 25d. Improved the overall health status of individuals in the community | 0.81 | |||||

| 25f. Resulted in the acquisition of additional financial support | 0.46 | |||||

| 25g. Improved the overall environment in the community | 0.87 | |||||

| Partnership capacity (i.e. communicative resources) | 0.65 | 2a. Partnership has skills and expertise to work effectively toward its aims | 0.78 | 0.57 | ||

| 2c. Partnership has diverse membership to work effectively towards its aims | 0.53 | |||||

| 2d. Partnership has legitimacy and credibility to work effectively towards its aims | 0.65 | |||||

| 2e. Partnership has ability to bring people together for meetings and activities | 0.70 | |||||

| 2f. Partnership has connections to political decision-makers, government agencies, other organizations/groups | 0.54 | |||||

| 2g. Partnership has connections to relevant stakeholders to work effectively towards its aims | 0.74 |

There are three second-order factors—community agency, reflexivity and transformation. Community agency was measured with a scale of community member involvement in research [32] with three subscales of background research, data collection, and analysis and dissemination. Community member involvement in research is the degree of engagement throughout the research and intervention process. It ensures that affected members have agency to shape problem definition and strategies to address the problem. The construct name, agency, reflects the change in response to our case study partners.

Reflexivity was measured with two subscales: participatory decision-making [32] and change in power relations [38]. Participatory decision-making reflects the degree of shared and collaborative decision-making. Change in power relations is the extent to which community members increase their research capacity relative to academic partners. These scales indicate reflexivity as they involve active change among the community and academic partners and result from careful consideration of partnership interactions.

Transformation was measured with two subscales: community transformation [38] and partnership capacity [39]. Community transformation is the extent of change related to policy, environment and financial resources for the community. Partnership capacity is the level of resources the partnership has to affect change. These subscales relate to transforming the resources and systems in the community.

We also included four subscales of partnership processes and four CBPR or health outcomes from the previously validated subscales to assess construct validity. The partnership processes included degree of trust in the partnership, disrespectful communication and whether CBPR principles toward community partners were followed [38]. The outcomes included overall change in community health, sustainability of the project and capacity building of individual partners and agencies [38]. Most of these were used for convergent validity, with disrespect used for divergent validity.

Data analysis

Factorial validity of the CCA scale was assessed with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 23.0. CFA was completed with all missing values replaced with series mean; while replacing data in this manner can be problematic, missing data were determined to be missing at random with a very small portion of missing values in the entire data set (<1%) and hence a minor concern. The scales were assessed using four fit indices: χ2 to df ratio (χ2/df < 3.0), comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI > 0.90) and standardized root mean-squared residual (SRMR < 0.08). Internal consistency of the scales was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha. Finally, bi-variate correlations matrix was used for construct validity (SPSS 23.0).

Qualitative methods

Research design and sampling

Qualitative data were collected in parallel with the surveys so they did not inform the conceptualization of scale. Rather, we sought in-depth historical and contemporary knowledge through seven case studies to uncover how the CCA is reflected in context, partnership processes, intervention design and outcomes. Case studies were selected from long-term partnerships (e.g. multiple grants) and purposefully diverse—urban/rural, health issue, and ethnic/racial and other identity subpopulations (see [21] for description). Though all cases had elements of the CCA within CBPR processes and outcomes, because of space limitations we invited community co-authors from two: (i) University of Rochester National Center for Deaf Health Research (www.urmc.edu/ncdhr); and (ii) Bronx Health REACH (BHR) faith-based initiative (http://www.institute.org/bronx-health-reach/about/), a partnership between the Family Urban Health Center with Bronx community partners. These two partnerships had elements of the CCA across the four domains of the model and represented distinct approaches. Partners from both partnerships are co-authors on this manuscript.

Data analysis

Using thematic analysis based on the CCA and supported by ATLAS.ti, we triangulated with the CES scales, confirming constructs of community voice/agency, power and transformation. For each interview (average 60 min), and focus group (∼90 min), we coded responses by community or academic member. Interviewees were chosen by the site coordinator, and were all seen as key members of the partnership; we did not analyse by their positions.

We coded both deductively and inductively. Deductively, we started from the four broad model domains to create thematic coding families. Within context for example, we coded governance, health issue and collaboration from the model, yet the themes we coded inductively had equal salience. New community description and project history subthemes led to deeper understandings of the role of socio-cultural historical contexts in enabling community members to exercise agency within the partnership. Inductive coding of community advisory structures was key to understanding how community agency was enacted in partnership processes. The domain of intervention/research led to inductive coding of cultural knowledge within interventions. In the outcome domain, we started deductively with community and university change codes. Subcodes were then drawn inductively from the data, such as community outcomes of transformations in power and cultural identity.

The research team (composed of eight faculty, students and staff) jointly coded the interviews from the first case study, with ongoing discussion for consensus and final code list. Two co-investigators, who differed by site, then conducted and coded the interviews, and wrote community narratives which were shared back with partnerships for iterative interpretation. Over 2 years, the entire research team conducted cross-case analysis iteratively for final cross-cutting themes. In sum, we used the four domains to frame the broad thematic analysis given the strong evidence we had developed over the past decade supporting the model. However, new subthemes and subcodes within these domains were inductively developed.

Results

Quantitative factorial and construct validity

The CFA achieved a good model fit and included three 2nd-order factors of the CCA, as conceptualized: χ2 (424) = 777.50, P < 0.001, χ2/df = 1.83, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.06. Table I displays the descriptive information for the second-order scales and the items and subscales comprising these scales. The three 2nd-order constructs had good internal consistency as well: agency/voice (α = 0.88); reflexivity (α = 0.88); and transformation (α = 0.77).

Pearson’s correlations were used to assess construct validity (see Table II). The CCA subscales are moderately correlated with each other revealing three distinct constructs. The three CCA scales were moderately correlated with partnership processes constructs of trust, CBPR principles–partner, CBPR principles—community, with the strongest correlations with the reflexivity scale followed by the transformation scale. All three CCA scales had moderate correlations with CBPR outcomes and health outcomes, again with transformation and reflexivity having larger correlations than agency/voice. This is consistent with our expectations, as agency is the means to reflectivity and transformation. The correlations provide strong evidence of convergent validity.

Table II.

Correlations of CCA subscales with dynamics and outcomes

| Construct | Voice/agency | Reflexivity | Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCA subscales | |||

| Voice/agency | 1.0 | ||

| Reflexivity | 0.48** | 1.0 | |

| Transformation | 0.31** | 0.43** | 1.0 |

| Convergent validity: partnership dynamics | |||

| Trust | 0.28** | 0.67** | 0.40** |

| Principles-community | 0.39** | 0.61** | 0.49** |

| Principles-partners | 0.40** | 0.65** | 0.47** |

| Convergent validity: outcomes | |||

| Change health | 0.13* | 0.31** | 0.59** |

| Sustainability | 0.40** | 0.58** | 0.47** |

| Partner capacity building | 0.31** | 0.45** | 0.45** |

| Agency capacity building | 0.34** | 0.50** | 0.55** |

| Divergent validity | |||

| Disrespect | −0.03 | −0.32** | −0.07 |

Correlations significant at

P < 0.001;

P < 0.01.

Finally, a single scale (disrespect) was used to assess divergent validity. Disrespect was not expected to be correlated with agency/voice and transformation as it is a micro-level indicator of negative interaction, and these two subscales relate to structural features of the partnership. However, since reflexivity is related to micro-level interaction, it was expected to be negatively related to disrespect. The correlations supported these expectations and provide support for the divergent validity of the CCA subscales.

Qualitative analyses of the CCA processes and outcomes

The National Center for Deaf Health Research (NCDHR), a Prevention Research Center at the University of Rochester funded by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in 2004, had a core research project to adapt the Weight-Wise intervention, originally created for English-speaking low-income populations. While retaining evidence-based components, NCDHR integrated Deaf linguistic and cultural framing by involving Deaf community members in all phases of the research [40, 41]. In addition, the University was responsive to community recommendations during construction of the NCDHR building, such as providing light-emitting doorbells in offices so a deaf University employee would know they had a visitor.

BHR, initially funded by a CDC REACH grant, starting with five churches in 2001, has expanded to over 70 churches and organizations. With later NIH funding, BHR developed a faith-based diabetes management program, which added cultural scriptures to health messages, as well as transformed church meal nutrition and successfully advocated, against the dairy industry, for low-fat milk in school lunches [42, 43]. Both partnerships were tightly woven integrated teams, with community members working within university teams, adding compositional representation and deeply shared knowledge and values, thus creating high-level bridging social capital among partners [23, 38].

CCA themes related to the CBPR model emerged in interviews and focus groups with each partnership: (i) context–the importance of socio-cultural history in identifying oppressive institutions and policies, and strategies for (re)claiming identity and equity; (ii) partnership processes–integration of community agency/voice into partnership structures and decision-making; (iii) intervention/research design–integration of cultural knowledge into interventions and research and (iv) outcomes–enhanced cultural identity and the re-balance of power through cultural pride and structural changes. Each is briefly reviewed, followed by a table of specific quotes.

Context

Contextual constructs, less explored through the surveys, assumed primary importance (see Table III). When asked ‘what was the most important thing to know about your partnership’s beginnings’, community members responded with socio-cultural histories. Bronx community partners identified segregation and present-day discrimination, as well as the role of black churches in Civil Rights and providing spiritual faith as black community power even in hard historical times. For NCDHR, hearing and deaf partners (from both University and community) shared conviction in Deaf community power as a distinct linguistic and cultural group. Each partnership identified valued cultural knowledge. For Bronx community members, it was knowledge of scripture; for Rochester, it was intimate knowledge of Deaf culture, as deaf individuals, friends and children of deaf adults.

Table III.

Themes within context in CBPR model

| History/description of population or place | Cultural grounding | |

|---|---|---|

| Bronx Health REACH |

|

‘Well, they made it clear from the Jump Street that if the community was going to experience wholeness that the black church and Latino church in this community must see health issues and concerns as a spiritual matter. Now, that’s what got my attention, when they made it spiritual’. (Male/Community) |

| National Center for Deaf Health | ‘If you don’t think that there’s something called Deaf culture, you need to spend more time with deaf people. There are all different cultures. Knowing the deaf, there’s a Deaf culture’. (hearing Male/University) |

|

Partnership processes

Although each partnership was highly integrated, to support greater community power, subcommittees (predominantly of community members) asserted dominance of community language/culture (see Table IV). Research staff and faculty who shared community identities participated in subcommittees. The Deaf Health Community Committee (DHCC), comprised ASL-fluent deaf and hearing adults, began meetings with researchers using bilingual interpreters and then continued only in ASL, after researchers left. BHR’s Community Resource Committee (CRC) was predominantly pastors and church lay health organizers, and Latino and Afro-Caribbean staff. These integrated structures opened opportunities for community agency. Community members saw the use of community language (including language of faith) in creating curricula and programs as highly significant in honoring core values. While Dutta [9] cautions against ‘translation’ as not representing the CCA, the deep cultural knowledge within subcommittees supported community agency for changes to research protocols, and also showcased respect for community leaders.

Table IV.

Themes within partnership processes in CBPR model

| Community structures that support community agency | Community agency in decision-making | |

|---|---|---|

| Bronx Health REACH | ‘Our CRC group has pastors, physicians, leaders in the public health arena, very important people with a lot of experience who come from different spheres; in their own world they are their leaders. People are used to listening to them. And there’s that level of respect that I think came from working together for many years’. (Male/Family Health Center) | ‘It’s a faith-based exercise and nutrition project; it really was developed initially by one of the faith-based health coordinators. One of those health coordinators actually developed this program initially’. ‘[it] came organically out of the church’. (Female/Family Health Center) |

| National Center for Deaf Health | ‘So our deaf committee members… they’re doing the data collection … They run recruitment … They’re involved with analysis…They’re involved in all steps along the way’ (hearing Female/University) ‘The DHCC is a committee that works in partnership with NCDHR…I always feel that research for an hour is good; and then we have our closed meeting. We don’t need the researchers, because often we’ve asked all the questions we need to ask…and we’re kind of done with them. The second hour we are free to breathe freely and sign ASL the way we like, and we don’t have to worry about being monitored’. (deaf Male/Community) | ‘One example was the K award from AHRQ to do the Deaf Healthcare Survey. He had a grant that we would recruit 75 deaf folks from the ER [emergency room] … And so he went to DHCC and said, ‘How would you feel if a research coordinator from NCDHR was in the ER? They approached you about the survey’. And [DHCC] said, ‘No way. We don’t want to see anyone we know. This is confidential. We’re at the ER for a reason. It’s not for being solicited for a research project’. And so we changed the protocol to work with the U of R[ochester] patient enrollers [not affiliated with NCDHR] who are students or research assistants that are in the ER recruiting for any study in the university’. (hearing Male/University) |

Intervention/research design

Increasingly, CBPR projects tailor ‘evidence-based’ interventions from one population to another (see Table V). Rather than superficial tailoring, however, each project prioritized community structures and agency, which enabled extensive (re)centering of interventions within core cultural/community knowledge and values that strengthened their own emotional connections. In the Bronx, faith was not just a ‘belief’ system, but scriptural values provided unique resonance with participants’ history of survival and resilience. In Rochester, ASL was adopted by both hearing and deaf partners for re-creating research instruments, such as the informed consent/study enrollment video, as a commitment to share power with the Deaf community. Neither of these partnerships remained at ‘surface’ cultural adaptations, but community members exercised their power through contextualizing interventions within profound community values, history and meaning-making.

Table V.

Themes within intervention/research design in CBPR model

| Impact on interventions | Impact on research design | |

|---|---|---|

| Bronx Health REACH | ‘The “Fine, Fit, and Fabulous” program…each element was attached to scriptural teachings that resonated with people, because their faith is a central element of who they are, of how they express themselves as human beings, how they try to live’. (Female/Family Health Center) | ‘…then the staff worked very hard with members of the church and the liaisons and pastors to develop a vocabulary and materials that reflected all of those really strong commitment[s] to the faith-based piece of the initiative’. (Female/Family Health) |

| National Center for Deaf Health | ‘…We’re taking proven models, proven to work in the hearing community … almost all of which deserve validation, and then within the context of the deaf community provides interesting context of intervention. So that’s where the science is. Then we moved it over to the deaf community’. (hearing Male/University) | ‘Our informed consent process for Deaf Weight Wise is an 18-minute ASL movie. It’s a scenario of two [deaf] researchers and two [deaf] participants; and it’s back and forth. [After the video,] participants sit down one on one with a researcher who’s sign fluent and ask their questions in ASL; then they sign a one-page English documentation of the consent form that says, “I watched the video. I understand Deaf Weight Wise. I asked my questions. I agree to participate”’. (hearing Female/University) |

Outcomes

Qualitative data provided elaboration and examples for the ‘structural transformations’ scale identified in the survey. For the Bronx, this meant influencing church policy (i.e. not serving sweetened beverages) or transforming power relationships, such as demanding the Department of Health not impose its own agenda (see Table VI). While Rochester started with a weight-wise curriculum from another population, their final products had major research impacts on the institutional review board (IRB) and use of ASL as the necessary research language for use with Deaf people. Revitalized cultural identity was an unmistakable finding of each of these projects, which, while not in Dutta’s [9] original conceptualization, does elevate what might be seen as superficial cultural sensitivity, to core support for communities creating their own actions based on their cultural meanings and pride.

Table VI.

Themes within outcomes in CBPR model

| Community power for structural transformation | Reinforcement of cultural identity | |

|---|---|---|

| Bronx Health REACH | ‘We said to DOH, “We’re not signing off.” Our coalition said, “no.” We said, “However, what we would encourage you to do is come back and educate our folks about the issues why sweetened beverage is a challenge.” And by doing that, we had more than half our churches voluntarily sign on that they would no longer serve sweetened beverages. That is a salutary lesson to DOH, that if you engage community rather than to try impose upon. The issues that you may not know because you do not live in those communities, you have a greater chance of success by engaging those communities’. (Female/Family Health) |

|

| National Center for Deaf Health | ‘Internally with our IRB, we have a long history with them with our first project, the deaf health ASL survey. They’d never been asked to approve any studies that were in ASL…. literally a couple of years of education and meetings with the IRB about research with deaf people. And with Deaf Weight Wise, about two years before we started, we started having meetings with them about the data collection tools were going to be in ASL, but we were giving them the English….So we got to a place where the IRB folks sort of trusted us that we had our best translators working from the English into ASL, and they should trust the English as best we could do to give them’. (hearing Female/University) |

|

Discussion

This study illustrates the usefulness of the CCA for CBPR-based health education research. The survey results enabled the development of the CCA scales based on Dutta’s [9, 10] framework of culture, community agency, reflexivity and structural transformation. The qualitative case studies substantiated and complemented the importance of socio-cultural-historic context and knowledge, and participatory committee structures that enabled community agency and reflexivity to ground interventions and research design. Qualitative examples showcased structural outcomes at the university and community level as well as cultural reinforcement. Several lessons are presented.

Scale of CCA

Our scale provides an effective way to operationalize the CCA. The scale recognizes key features and recognition of power differentials identified by scholars when engaged with indigenous and other ethnic minority communities [3, 44]. Further, the scale can be useful for health education and promotion, and public health scholars and practitioners interested in a substantive approach to evaluating cultural agency and fit in an intervention. We encourage using the scale as a self-reflection tool and for outcome evaluation, in its capacity to identify associations between partnering practices and outcomes.

Associations with partnering practices and outcomes

CBPR engages communities to participate in health intervention research in meaningful and culture-centered ways. Our study provides empirical findings that the CCA scales have positive associations with partnering practices and CBPR outcomes, consistent with the evidence suggesting CBPR and the CCA have positive outcomes for vulnerable populations [19, 45, 46].

Our qualitative data provide triangulation, identifying community power and agency through subcommittees, and cultural reinforcement and structural outcomes within research institutions and outside agencies [47]. Community partners identified a temporal flow with community committees facilitating community-driven decisions on interventions and research methods. They noted the importance of research team members from the community, enabling bridging to community values. Our mixed-methods approach substantiates hypotheses about the importance of CCA for validating community participation in research for improved health. Overall, the scale should be viewed for CBPR, but may apply to other health interventions to help address deep structure cultural issues [4] for reducing health inequities.

Integrating cultural context and knowledge

In addition to supporting survey results, qualitative data highlighted multiple interpretations of culture, so that partnership worldviews can be comprised both academic and community perspectives [4, 13] even though our scale reflected a uniform factor structure from partnerships. Each partnership benefited from community committees which had agency to change research protocols and interventions for robust and valid research. Neither of them simply used superficial imagery, but integrated social-historical contexts as sources of community power. They also understood the value of reinforced cultural pride for social change, such as support for faith-based spiritual language and use of ASL. These findings therefore suggest that researchers incorporate a multi-dimensional, socio-ecological and empowerment-oriented perspective of culture in order to avoid superficial cultural adaptations that reinforce health inequities [3, 9].

Connections to empowerment

While this manuscript focuses on Dutta’s definitions, the culture-centeredness term parallels definitions of community empowerment [48, 49], whether based in Paulo Freire’s reflexive reflection/action cycle [50], community psychology’s emphasis on mastery [51] or public health/health education’s literature on personal-societal transformations [52, 53]. In our continued inquiry into CBPR practices and outcomes, our NIH-funded Engage for Equity (E2) study (2015–2020, https://engageforequity.org), has identified collective empowerment as a complementary higher-order construct, which encompasses agency, reflexivity, fit to community culture and CBPR principles. Both collective empowerment and culture centeredness recognize the importance of agency and equalized power relations within partnerships to achieve health equity outcomes.

Importance of CCA for CBPR conceptual model

The findings provide empirical support for integrating CCA within the CBPR conceptual model. Both approaches emphasize community agency, by calling for meaningful community engagement in the definition of problems and identification of solutions for health improvement [9, 21]. Theoretically, the CCA however extends the CBPR model by more explicitly committing to reflexivity and structural transformation.

Reflexivity for the CCA focuses on navigating power differences and privilege to ensure community agency; thus it comes primarily from a critical perspective. This approach is consistent with a Freirian approach found in much CBPR, although this is not always present along the continuum of community-engaged research. Further, sometimes the focus on reflexivity is about improving partnership practice, and thus is a utilitarian and not a critical approach [1]. This analysis of CCA influenced the current Engage for Equity study to incorporate collective empowerment resulting from reflexivity and agency, transforming the CBPR conceptual model beyond its 2008 version [21].

Second, the CCA has an explicit focus on structural transformation and resources to create change [9]. In contrast, many community-engaged research projects may focus on culturally adapting an intervention, without focusing on structural change. Dutta labels these approaches culturally sensitive and not culture centered [9]. The CBPR model also reciprocally extends the CCA, by naming cultural reinforcement as a structural outcome, recognizing identity as a powerful driver of social change. In total, however, integration of CCA has strengthened the commitment by CBPR partnerships and other community-engaged research projects to seek external structural changes as core to reducing health inequities [1].

Limitations

The study has limitations in the use of a cross-sectional survey and case studies focusing only on NIH-funded partnerships. With the cross-sectional nature of the data, we are cautious about making causal/temporal inferences particularly as they relate to health improvement or reduced inequities. Future research will be needed to establish the direct impact on these outcomes. Further, there could have been a selection bias toward including community-engaged projects with funding. Although this is the first scale of the CCA, it is not complete. The subscale of community agency/voice focuses on community involvement in research phases and not on other organizing efforts. Reflexivity includes shared decision-making and changing relationships, yet does not measure self-reflection on partnering specifically. Integration of community or cultural knowledge was not measured. Transformation includes perceptions of transformed programs/policies and partner capacity to succeed, but does not include specific changed structures or social determinants, nor communicative resources. The current Engage for Equity study as an intervention trial is seeking to address these gaps through refined instruments and further analyses of the impact of CCA processes on outcomes.

Conclusion

Despite these potential limitations, however, this study offers the first integration and measurement of the CCA within community–academic research partnerships. The findings are powerful and may be applicable to other community health research projects. In sum, our CCA findings provide insights into complex dynamic notions of culture consistent with recent writings on deep structures of culture and collaborative knowledge creation. Ensuring cultural dimensions of community agency, reflexivity and transformation throughout the participatory research process may have strong implications for the goal of health equity for all.

Acknowledgements

We thank many community and academic team members who participated in the ‘Research for Improved Health’ surveys and case studies for their commitment and belief in the power of partnerships to enhance community health. We appreciate our own NARCH partnership, which gave us greater insights into the struggles and importance of supporting community agency, reflexivity and structural transformation: the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center (with thanks to PIs, Dr Sarah Hicks Kastelic and Dr Malia Villegas); with the Universities of Washington (co-PI, Dr Bonnie Duran) and New Mexico (co-PI, Dr Nina Wallerstein).

Funding

‘Research for Improved Health’ was a National Institutes of Health-funded Native American Research Centers for Health (NARCH) V study, supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences in partnership with the Indian Health Service (U26IHS300009 and U26IHS300293), with additional funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. Bronx Health REACH was supported, in part, by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (5R24 MD001644) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5U58DP000943); Health Resources Services Administration. The University of Rochester National Center for Deaf Health Research was supported, in part, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP001910 and U48DP005026). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J. et al. (eds). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson B, Molina Y, Viswanath K. et al. Strategies to empower communities to reduce health disparities. Health Aff 2016; 35: 1424–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kagawa-Singer M, Dressler WW, George SM. et al. The Cultural Framework for Health: An Integrative Approach for Research and Program Design and Evaluation. Bethesda, MD: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, 2015, 1–324. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kagawa-Singer M, Dressler W, George S.. Culture: the missing link in health research. Soc Sci Med 2016; 170: 237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS. et al. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis 1999; 9: 10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Airhihenbuwa C. Health and Culture: Beyond the Western Paradigm. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wallerstein N, Duran B.. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 2010; 100: S40–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Airhihenbuwa C, Liburd L.. Eliminating health disparities in the African American population: the interface of culture, gender, and power. Health Educ Res 2006; 33: 488–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dutta MJ. Communicating about culture and health: theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Commun Theory 2007; 17: 304–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dutta MJ. Communicating Health: A Culture-Centered Approach. Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams DR, Mohammed SA.. Racism and health II: a needed research agenda for effective interventions. Am Behav Sci 2013; 57: 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Basu A, Dutta MJ.. Sex workers and HIV/AIDS: analyzing participatory culture-centered health communication strategies. Hum Commun Res 2009; 35: 86–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dutta MJ, Anaele A, Jones C.. Voices of hunger: addressing health disparities through the culture-centered approach. J. Commun 2013; 63: 159–80. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Coombe CM. et al. A community-based participatory planning process and multilevel intervention design: toward eliminating cardiovascular health inequities. Health Promot Pract 2011; 12:900–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bogart LM, Uyeda K.. Community-based participatory research: partnering with communities for effective and sustainable behavioral health interventions. Healthy Psychol 2009; 28: 391–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bradbury H. (ed.). The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL. et al. Reflections on researcher identity and power: the impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Crit Sociol 2015; 41: 1045–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minkler M, Garcia AP, Rubin V. et al. Community-based Participatory Research: A Strategy for Building Healthy Communities and Promoting Health through Policy Change. Berkeley: PolicyLink and School of Public Health, University of California, 2012.

- 19. O'Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S. et al. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hicks S, Duran B, Wallerstein N. et al. Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2012; 6: 289–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B. et al. What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N (eds). Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes, 2nd edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2008, 371–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kastelic SL, Wallerstein N, Duran B. et al. Socio-ecologic framework for CBPR: development and testing of a model In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, Minkler M (eds). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, 3rd edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2018, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Belone L, Lucero J, Duran B. et al. Community-based participatory research conceptual model: community partner consultation and face validity. Qual Health Res 2016; 26: 117–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spivak GC. The Post-Colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues. New York, NY: Routledge, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beverley J. Subalternity and Representation: Arguments in Cultural Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dutta MJ, Basu A.. Health among men in rural Bengal: exploring meanings through a culture-centered approach. Qual Health Res 2007; 17:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ford AL, Yep GA, Working along the margins: developing community-based strategies for communicating about health with marginalized groups In Thompson TL, Dorsey AM, Miller KI. et al. (eds). Handbook of Health Communication. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2003, 241–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cooke B, Kothari U.. Participation: The New Tyranny? New York, NY: Zed Books Ltd, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chilisa B. Indigenous Research Methodologies. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dutta MJ, Basu A.. Negotiating our postcolonial selves: from the ground to the ivory tower In Jones SH, Adams TE, Ellis C (eds). Handbook of Autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc, 2013, 143–61. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mosse D. People’s knowledge’, participation and patronage: operations and representations in rural development In Cooke B, Kothari U (eds). Participation: The New Tyranny? New York, NY: Zed Books, 2001, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones F. et al. An exploration of the effect of community engagement in research on perceived outcomes of partnered mental health services projects’. Soc Ment Health 2011; 1: 185–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fang ML, Woolrych R, Sixsmith J. et al. Place-making with older persons: establishing sense-of-place through participatory community mapping workshops. Soc Sci Med 2016; 168:223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Catalani C, Veneziale A, Campbell L. et al. Videovoice: community assessment in post-Katrina New Orleans. Health Promot. Pract. 2012; 13:18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oetzel J, Zhou C, Duran B. et al. Establishing the psychometric properties of constructs in a community-based participatory research conceptual model. Am J Health Promot 2015; 29, e188–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lucero L, Wallerstein N, Duran B. et al. Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. J Mix Methods Res 2018; 12, 55–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tastle WJ, Wierman MJ.. An information theoretic measure for the evaluation of ordinal scale data. Behav Res Methods 2006; 38:487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oetzel JG, Villegas M, Zenone H. et al. Enhancing stewardship of community-engaged research through governance. Am J Public Health 2015; 105:1161–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Granner ML, Sharpe PA.. Evaluating community coalition characteristics and functioning: a summary of measurement tools. Health Educ Res 2004; 19, 514–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barnett S, Klein JD, Pollard RQP Jr.. et al. Community participatory research with deaf sign language users to identify health inequities. Am J of Public Health 2011; 101:2235–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barnett S, McKee M, Smith SR. et al. Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: opportunity for social justice. Prev Chronic Dis 2011; 8, A45.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gutierrez J, Devia C, Weiss L. et al. Health, community and spirituality: evaluation of a multicultural faith-based diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Educ 2014; 40, 214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kaplan SA, Calman NS, Golub M. et al. The role of faith-based institutions in addressing health disparities: a case study of an initiative in the southwest Bronx. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2006; 17, 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peterson JC. CBPR in Indian country: tensions and implications for health communication. Health Commun. 2010; 25, 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Duran B, Oetzel J, Pearson C. et al. Promising practices and outcomes: learnings from a CBPR cross-site national study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46. Oetzel J, Wallerstein N, Duran B. et al. Impact of participatory health research: a test of the CBPR conceptual model: pathways to outcomes within community-academic partnerships. Biomedical Research Int., 2018, Article ID 7281405, doi: 10.1155/2018/7281405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47. Wallerstein N, Muhammad M, Avila M. et al. Power dynamics in community based participatory research: a multi-case study analysis partnering contexts. Histories and Practices Health Education and Behavior, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Rushing SNC, Hildebrandt NL, Grimes CJ. et al. Healthy & empowerment youth: a positive youth development program for Native youth. Am J Prev Med 2017; 52: S263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Young S, Patterson L, Wolff M. et al. Empowerment, leadership, and sustainability in a faith-based partnership to improve health. J Relig Health 2015; 54:2086–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory: psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis In: Rappaport J, Seidman E (eds). Handbook of Community Psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2000, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wallerstein N. What is the evidence of effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, World Health Organization, 2006. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74656/E88086.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 53. Wong NT, Zimmerman MA, Parker E.. A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. Am J Community Psychol 2010; 46:100–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]