Abstract

Background

Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of mental disorders and a high incidence of morbidity, but if diagnosed and treated promptly individuals can benefit from full recovery. However, there are numerous problems at the healthcare interface (i.e. primary and secondary care) for eating disorders. It is important to examine these to facilitate appropriate, seamless treatment and improve access to specialist care.

Aims

To examine the current literature on the experiences and perspectives of those across healthcare interfaces for eating disorders, to include individuals with eating disorders, people close to or caring for those with eating disorders such as family and friends, and health professionals.

Method

To identify relevant papers, a systematic search of electronic databases was conducted. Other methods, including hand-searching, scanning reference lists and internet resources were also used. Papers that met inclusion criteria were analysed using a systematic methodology and synthesised using an interpretative thematic approach.

Results

Sixty-three papers met the inclusion criteria. The methodological quality was relatively good. The included papers were of both qualitative (n = 44) and quantitative studies (n = 24) and were from ten different countries. By synthesising the literature of these papers, three dominant themes were identified, with additional subthemes. These included: ‘the help-seeking process at primary care’; ‘expectations of care and appropriate referrals’ and ‘opposition and collaboration in the treatment of and recovery from eating disorders’.

Conclusions

This review identifies both facilitators and barriers in eating disorder healthcare, from the perspectives of those experiencing the interface first hand. The review provides recommendations for future research and practice.

Declaration of interest

None.

Keywords: Eating disorders, healthcare interface, patients and carers, systematic review, thematic synthesis

Background and rationale for review

Eating disorders are relatively rare but are associated with a multitude of physiological, psychological, social and economical complications and have the highest mortality of all mental disorders.1–3 Evidence suggests that prompt diagnosis and early intervention improves recovery prospects.4 However, eating disorders are difficult to diagnose and treat.3,5

Generally, healthcare is regarded as a partnership between patients and professionals. For eating disorders, however, this relationship can be ambivalent, with inconsistencies in healthcare.6,7 Primary care (i.e. community-based generalist medical care) is usually the first port of call for any health-related complaint and the setting where many conditions are diagnosed and managed. Some disorders may require specialised treatment and transitions or co-management across the interface between primary and secondary (i.e. specialist) care. The coordination between different levels of care can be fraught.6 For example, family physicians/general practitioners (GPs) often feel unequipped to identify and manage eating disorders and prefer to pass care to specialist services.8 However, specialist services are often significantly under-resourced, overburdened and unable to accept high numbers of referrals. As a result, patients with eating disorders may be left untreated, facing long waiting lists, inappropriate referrals and prolonged illness, exacerbating eating disorders and decreasing the likelihood of recovery.9

In the UK, up to 1.25 million people are affected by eating disorders, yet there are relatively scarce resources available to treat them.10,11 The National Health Service (NHS) proposes to deliver better healthcare based on ‘principles and values’. English, Welsh and Scottish NHS healthcare systems all espouse principles and values for better integrated service for all patients with patient-centred, shared decision-making and better interagency working.12,13,14

Despite variation, healthcare has many similarities internationally.6 Most healthcare systems face challenges of rising cost and increasing demand as quality of care improves,15 with many governments committed to improving primary–secondary transitions.16 Several countries successfully use similar principles and values to the UK. In New Zealand and the USA, shared partnerships and shared responsibility in treatment in distributing resources more efficiently have improved health outcomes. In the USA, more investment in primary care has successfully shifted care to out-patient clinics. In Sweden, patient-centred care is prioritised – looking at healthcare through the ‘patient's eyes’ and in the Netherlands, ‘neighbourhood care’ is optimised.15

Given the commonality of these challenges across different healthcare systems, it is important to review the current literature on eating disorder health provision at the primary–secondary care interface at an international level, to explore the facilitators and barriers existing in eating disorder healthcare, and then draw conclusions that can underpin recommendations to ensure eating disorders are diagnosed and treated in line with principles of good clinical practice.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this paper was to systematically review and thematically synthesise the current literature on the primary and secondary care healthcare interface for eating disorders. These included a range of perspectives and experiences of: individuals with eating disorders; people close to individuals with eating disorders, such as family members, loved ones and close friends; and health professionals working with eating disorders. This review was conducted to gain a better understanding and a more comprehensive account of the healthcare interface for eating disorders. To do this, data was collected from mixed methods primary studies to assess and understand a range of different experiences and perspectives and examine the facilitators to and barriers of eating disorder healthcare to provide recommendations for improvements in future research and practice.

The research questions we asked were: (a) what are the current facilitators and barriers across primary and secondary eating disorder healthcare services; and (b) what conclusions can be drawn from the international literature to improve the healthcare services for eating disorders?

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews by PRISMA 2009 Checklist.17 Studies were considered for inclusion for the review if they met the predetermined study eligibility checklist shown in Appendix 1. A comprehensive search of electronic databases was conducted in May to September 2017. These databases were: Web of Science, PubMed, APA PsychNET, PsycINFO, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Science Direct and Social Sciences Citation Index. No restrictions were placed on geographic location or publication date. However, language and methodological filters were applied to ensure that studies were restricted to the English language only, and study designs were primary studies only. In addition, searches also included hand-searching, scanning of reference lists and searching internet resources. All databases and other resources were searched using a combination of search keywords and terms. These included keywords relating to population groups (for example ‘patients’, ‘sufferers’, ‘people with an eating disorder’, ‘service user’; ‘family’, ‘carer’, ‘loved one’; ‘health professionals’, ‘primary’, ‘secondary’ and so on); types of eating disorders (for example ‘anorexia nervosa’, ‘bulimia nervosa’, ‘binge-eating disorder’ and so on); and types of treatment settings (for example ‘in-patient’, ‘out-patient’, ‘primary’, ‘community’, ‘GP practice’). Each search term was adapted for individual databases or other resource types as needed, matching them against titles, abstracts and subject descriptors.

Data extraction and synthesis

The retrieved studies were screened for relevance and rated against the inclusion/exclusion criteria for further consideration by two reviewers (G.J. and J.T.) using a stepwise approach, for example screening for titles and abstracts. Eligible studies were then obtained in full-text and reviewed. Data were extracted using a data extraction form developed by the reviewers. The extracted data included: study characteristics and design, lived experiences and personal perspectives of outcomes.

To analyse the data, studies were synthesised and interpreted using a qualitative narrative synthesis methodology that integrates and compares findings, by looking for themes or constructs across individual studies.18 This process comprised using the extracted data from all three population groups, which were then subcategorised using a thematic approach to the data to identify emerging themes, to enable exploration of people's perceptions and experiences. An interpretivist approach was applied to this synthesis to deepen understanding of the findings across the papers and go beyond the original findings to generate new constructs and explanations.19 To do this, the data was extracted and coded, that is, data was read line-by-line, and relevant data was categorised into list-form, under specific headings and subheadings. This created descriptive themes of the data, then similar codes from each additional paper were grouped together to synthesise the data in to a more analytical format to construct themes, from which dominant themes and subthemes were then created. These themes were drawn from similarities identified in the data and matched across the three participant groups. Each identified category, heading/subheading and descriptive themes, and their analytical format were double-checked and double-coded, and any discrepancies were then discussed and resolved. This process was conducted by two of the authors (G.J. and J.T.).

Quality assessment

The studies were assessed by one author (G.J.) and a proportion (20%) of these were additionally double-coded by another (J.T.). Any discrepancies were then discussed and resolved. This was assessed using an adapted version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for both qualitative research and randomised controlled trials.20 The checklist consisted of four subscales (10 items) reporting: aims, methods, design, recruitment, data collection, bias, ethics, analysis/testing, findings/conclusions, and value. The highest possible score was 20. A ‘good’ rating score for each subitem was allocated a score of ‘2’, ‘fair, 1’ and ‘poor, 0’. The cut-off threshold for inclusion was set relatively low (score >10) as this is a review of perspectives and experiences, not of effectiveness or quality.

Results

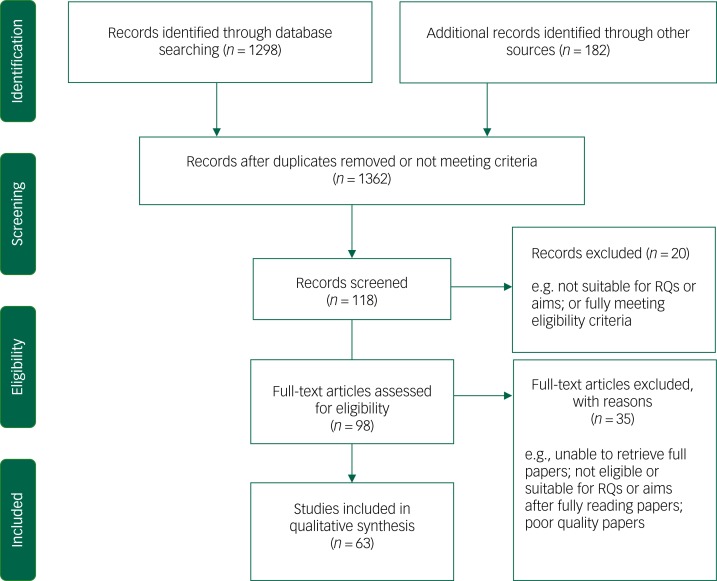

An initial scope of the electronic databases and the internet (such as Google scholar and Google) generated a total of 1480 papers. Of these, 1362 papers were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts, as not meeting full criteria. The remaining 118 papers were retrieved in full, after which, a further 20 papers were excluded. A data extraction and quality assessment of the remaining 98 papers was conducted, resulting in 35 papers being excluded. In total, 63 papers met the inclusion criteria for the review.21–83 Table 1 provides the quality assessment scoring of the 63 selected papers and Fig. 1 provides an overview of the selection process as a flow diagram.

Table 1.

Quality assessment score

| Author | Date | Score (out of 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Tierney21 | 2008 | 19 |

| Rie et al.22 | 2006 | 18 |

| Clinton et al.23 | 2014 | 17 |

| Linville et al.24 | 2012 | 19 |

| Robinson et al.25 | 2012 | 18 |

| Bravender et al.26 | 2016 | 18 |

| Sheridan & McArdle27 | 2016 | 19 |

| Boughtwood & Halse28 | 2010 | 19 |

| van Ommen J et al.29 | 2009 | 19 |

| Rosenvinge & Klusmeier30 | 2000 | 17 |

| Reid et al.31 | 2008 | 19 |

| Gulliksen et al.32 | 2015 | 19 |

| Gullisken et al.33 | 2012 | 19 |

| Nilsson & Hagglof34 | 2006 | 19 |

| Zugai et al.35 | 2013 | 19 |

| Federici & Kaplan36 | 2008 | 17 |

| Fox & Diab37 | 2015 | 18 |

| Smith et al.38 | 2016 | 18 |

| Escobar-Koch et al.39 | 2010 | 18 |

| Swain-Campbell et al.40 | 2001 | 19 |

| Dimitropoulous et al.41 | 2015 | 19 |

| Pettersen & Rosenvinge42 | 2002 | 19 |

| Grange & Gelman43 | 1998 | 18 |

| Lindstedt et al.44 | 2015 | 18 |

| Walker & Lloyd45 | 2011 | 19 |

| Paulson-Karlsson & Nevonen46 | 2012 | 18 |

| Colton & Pistrang47 | 2004 | 19 |

| Zaitsoff et al.48 | 2016 | 19 |

| Offord et al.49 | 2006 | 19 |

| Rance et al.50 | 2015 | 18 |

| Clinton et al.51 | 2004 | 19 |

| Schoen et al.52 | 2012 | 19 |

| Evans et al.53 | 2011 | 19 |

| Halvorsen & Heyerdah54 | 2007 | 19 |

| Roots et al.55 | 2009 | 19 |

| McMaster et al.56 | 2004 | 19 |

| Winn et al.57 | 2004 | 19 |

| McCormack & McCann58 | 2015 | 19 |

| Honey et al.59 | 2008 | 19 |

| Tierney60 | 2005 | 19 |

| Cohn61 | 2005 | 18 |

| Haigh & Treasure62 | 2003 | 18 |

| Reid et al.63 | 2010 | 19 |

| Currin et al.64 | 2009 | 19 |

| Bannatyne & Stapleton65 | 2016 | 19 |

| Burket & Schramm66 | 1995 | 19 |

| Boule & McSherry67 | 2002 | 19 |

| King & Turner68 | 2000 | 17 |

| Linville et al.69 | 2010 | 19 |

| Linville et al.70 | 2012 | 19 |

| Walker & Lloyd71 | 2011 | 19 |

| Vanderlinden et al.72 | 2007 | 19 |

| Jones et al.73 | 2013 | 19 |

| Masson et al.74 | 2009 | 19 |

| Johnston et al.75 | 2007 | 19 |

| Anderson et al.76 | 2016 | 18 |

| Banas et al.77 | 2013 | 19 |

| Johansson et al.78 | 2015 | 19 |

| Ramjam79 | 2004 | 18 |

| Girz et al.80 | 2014 | 19 |

| Hay et al.81 | 2007 | 19 |

| Ryan et al.82 | 2006 | 19 |

| Hunt & Churchill83 | 2013 | 19 |

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of selection of papers.

RQs, (a) What are the current facilitators and barriers across primary and secondary eating disorder healthcare services? (b) What conclusions can be drawn from the international literature to improve the healthcare services for eating disorders?

Methodological quality and study characteristics

The quality of the included papers was considered to be good to fair. All these papers were rated highly for design, methodology, recruitment, analysis and overall value. Therefore, all 63 papers were considered of an appropriate quality for inclusion in this review.

The included papers consisted of qualitative methodologies (n = 44), including semi-structured/in-depth interviews or focus groups and quantitative methodologies (n = 24) using questionnaires or online essays (63 papers in total, but some had mixed-method approaches – n = 68 methodologies). Of the included papers, the sample size varied substantially, ranging between 5 to 1522 participants. The samples were a mix of ages and genders. The included papers were published between the years 1995 and 2016. The studies were conducted across a range of geographic locations, including the UK and Ireland (n = 20), USA and Canada (n = 18), Australia and New Zealand (n = 13), Sweden and Norway (n = 11), and Netherlands and Belgium (n = 2). The population groups of these studies included individuals with eating disorders across a range of eating disorder types and severities (n = 37), family/friends (n = 10) and health professionals (n = 21).

The settings of the included papers of individuals with eating disorders and family/friends were ‘in-patient’ (child, adolescent, adult, eating disorders and mental health) (n = 17), drop-in specialist eating disorder centres (n = 2), university centres (n = 1), out-patient (n = 8), community recruitment/in home settings (n = 8), general medical wards/hospital (n = 4), private practice (n = 1) or online resources (n = 1).

For health professionals, the reported occupations/settings included: specialist eating disorder clinicians, medical doctors and nurses (GP practice, general ward, paediatric, mental health), psychiatrists, psychologists, dieticians, obstetricians, gynaecologists, counsellors, therapists (psychiatric, occupational), social workers, health visitors, midwives, dentists and student/fellow/resident health professionals. The characteristics for each paper are outlined in supplementary Table 1 (available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.48).

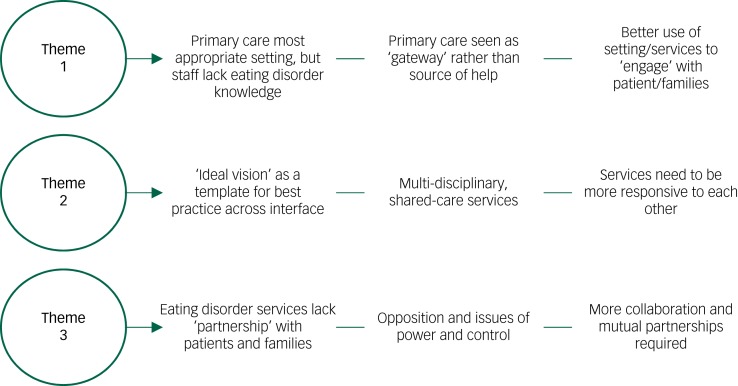

Summary of thematic analysis

By gathering the data and comparing the types of perspectives and experiences, three dominant themes emerged from the synthesis of the studies to allow for similarities and disparities to emerge and provide a comprehensive insight into the functions and barriers of the healthcare interface for eating disorders. The dominant themes and the subthemes are outlined in detail below. Appendices 2–4 provide a summary of each theme.

Theme 1: the help-seeking process

The first dominant theme that emerged from the literature is the help-seeking process and the primary care setting. This entails two subthemes and describes the process of individuals with eating disorders and family/friends of those with eating disorders seeking professional help in primary care settings, and the professional role of the primary health professionals in this process.

Subtheme 1: the help-seeking process at its current state

Individuals with eating disorders’ perspective of barriers to care and unhelpful experiences

In the literature, individuals with eating disorders considered primary healthcare the most appropriate and opportunistic setting to diagnose eating disorders and intervene in the first instance.1,10,12,24 Identified primary healthcare professionals included a GP/family physician or primary practice nurse,1,2,10,12,24,32,33 social worker,1,33 dietician,33 counsellor or psychologist.1,10,12,33 However, the health professionals in primary care settings were reported as presenting challenges and difficulties at the early stages of help-seeking. Individuals with eating disorders reported lack of eating disorder experience, understanding and knowledge among primary care professionals, particularly among GPs, practice nurses and social workers.1,2,5,10,12,19,21,25 Furthermore, frequent failure to detect eating disorder symptoms and provide a timely diagnosis was described.1,19 For individuals with eating disorders, primary care professionals not only lacked time and resources5,30 to diagnose and treat eating disorders, but were also ‘uninterested’ in eating disorders, believing it is simply a matter of ‘just eating’,25 or focused on physical symptoms of an eating disorders.19,25 In consequence, diagnosis of an eating disorders often only occurred when physical symptoms became severe and pronounced.1,19,25 However, even in severe cases, long waiting lists and a lack of resources with no guarantee of admission and treatment by more specialised services for eating disorders were major barriers.1,2,5,19,21,25,30 For individuals with eating disorders, the primary care service was described as an ‘obstacle’ or ‘barrier’1,19,33 to care, rather than the first port of call or effective ‘gate-keepers’ to specialist services.19

Family/friends’ perspective of barriers to care and unhelpful experiences

Likewise, for family/friends of individuals with eating disorders, help-seeking was initially sought in primary care or community settings such as GP practices and schools,36,37,38,42 but self-help books, internet resources, support-based organisations or private treatment were where most of the ‘useful help’ was located.36,37 For some family/friends, primary health professionals were helpful37,38,39,40 in terms of providing ‘active support’, without blame or judgement.38 Some described ‘thorough and competent’ primary care professionals.39 However, others found primary care a negative experience,38 feeling ‘fobbed off’.40 They reported that primary care professionals lacked eating disorder knowledge37,38,39 and the training required to diagnose and respond to eating disorders.42 They did not provide clear advice39 or provide essential management of eating disorders.37,42 Knowledge of available treatment options37,38 and the ability to negotiate with other healthcare systems to get access to referrals was poor.36,37,38,42 This caused ‘frustration and anger’38 and ‘resentment’ towards the professionals.36 The process of help-seeking was described as a ‘long arduous journey’ by family/friends,36 and some described how their own resourcefulness and inexhaustible search for help ultimately helped the person with an eating disorder obtain the treatment they need – which is about being ‘not prepared to give up’ and do ‘whatever is necessary to aid recovery’.36

Healthcare professionals’ perspective of barriers to care and unhelpful experiences

Professionals in primary care settings (for example GP practices, general wards, student/resident placements) described their professional role regarding eating disorders as a ‘double-bind’.63 They faced challenges and difficulties with individuals with eating disorders, their families and the eating disorder healthcare interface itself. Primary care professionals argued that individuals with eating disorders are difficult and challenging63 and create tension between all parties.63 They felt that people with eating disorders often lack motivation and adherence with treatment, with much of the drive for help-seeking and recovery coming from the families.43,46,47,48,49,63 Therefore, some primary care professionals were reluctant to work with eating disorders,51 with expressions of ‘frustration’,46,48 ‘resentment’45 and ‘irritability and disgust’ in the physical comorbidities,45,47 considering eating disorders as being ‘low prestige’ compared with other illnesses,45 with some stating they ‘don't like’ or ‘don't want to work with them’.46,56 Other primary care professionals indicated that they just ‘don't’, or ‘don't want’ to screen for eating disorders,46,49,55,57 as they find them time consuming or too complex,43,46,47,49,50,51 or just preferred to diagnose eating disorders rather than manage their care and treatment.47,53,60 Yet others were frustrated they ‘can't work’ with eating disorders,43,45 expressing a wish to be trained in eating disorders, because their role in detecting eating disorders symptoms was important.55,57

Primary care professionals saw the lack of training and resources in eating disorders as a barrier43 and felt that frustration caused negative attitudes that then impeded therapeutic relationships.43 It was widely recommended that a well-validated universal screening protocol for eating disorders would build confidence in primary care settings.49,50,53,55

Primary care professionals insisted that the challenges of working with eating disorders and professional negative attitudes were associated with ‘clinical’ problems44 such as feeling unequipped to diagnose and intervene with eating disorders50,57 because of a lack of eating disorder experience,43,65,56,58,63 knowledge/understanding,43,44,49,56 and adequate training and skills.43,45,47,49,50,51,60 They identified larger-scale ‘organisational’ problems51 that eating disorders are considered specialist disorders and requiring specialised care.43 However, they recognised that specialist care referrals are often unavailable or unobtainable;43,47,49 thus, primary care professionals were faced with challenges of trying to make referrals to inaccessible specialist treatment.49,55,63

Subtheme 2: utilising the primary care setting

In the literature, individuals with eating disorders suggested that the early stages of contact with a primary care professional needs to be a ‘positive experience’12 and this is greatly influenced by two factors. First, they expected sufficient knowledge of eating disorders and good interpersonal skills among primary care professionals.12 Second, they expected sensitivity regarding eating disorder ‘control’.1,12,14,32 For individuals with eating disorders, anxiety, ambivalence and resistance to treatment and/or help-seeking are often grounded in a fear of ‘losing personal control’.12,32 Because individuals with eating disorders often approached help-seeking with mixed feelings and motives, they felt that the professionals should emphasise ‘facilitating positive reactions’, encouraging individuals with eating disorders to speak openly rather than attempting to change behaviours and fix the eating disorder.12,32,41 This would allow individuals with eating disorders to feel they are in good hands, yet ‘feel safe and listened to’12 and able to sustain some personal control and the ability to take responsibility for their own actions.12,14,41 For individuals with eating disorders, this was a crucial point early in the help-seeking, which was necessary to enable them to be ready to change and seek recovery – a ‘testing the waters’32 or a tentative ‘action stage’ in eating disorder treatment.12,14,16,22,24 Being an active agent throughout treatment and into recovery was described in the literature as ‘turning points’ and success stories were described as ‘internal motivation’ or ‘want(ing)’ help,1,4,16,22,23,27,54 which depended greatly on ‘timing’ and being in the right place at the right time.12,22,24 Therefore, a therapeutic approach was crucial at earlier stages of help-seeking in primary care, because if ‘positive perceptions at help-seeking are formed as a result of this initial attempt, then future treatments were more effective in altering disordered eating behaviours’.32

Despite difficulties, studies suggested efforts were needed to better utilise the primary care setting as an opportunity to encourage the ‘action’ stage from individuals with eating disorders by providing supportive and therapeutic relationships14,16,22 and offering a sense of safety, commitment and validation11 while maintaining a mutual relationship among all parties as mutual ‘agents of change’.36,41 Primary care professionals could potentially help turn the first highly ambivalent consultation into a positive experience or successful turning point.12 A successful first encounter at primary care was described as a potential ‘powerful catalyst’ enable further treatment of and recovery from eating disorders.14 Appendix 2 outlines the key points from theme 1.

Theme 2: expectations of care and appropriate referrals

The second dominant theme is the ‘expectations of care and appropriate referrals’. This theme entails two subthemes. This looks at the ‘ideal’, and the functions and barriers surrounding the assumed ‘best’ eating disorder service.

Ideal characteristics of care and treatment

Individuals with eating disorders and their family/friends said ‘one professional’ could make a real difference in eating disorder care and treatment.54 This ‘good’ professional, regardless of whether they belonged to primary or secondary care services, was characterised as someone they can trust,27,30 and build a strong therapeutic relationship with,7,15,22,24,25,28,33 who is respectful and empathic.1,2,5,7,11,13,15,17,18,19,22,25,33,41 This ‘good professional’ needed to be available and consistent7,13,15,22 and have a sufficient understanding,5,11,12,13,18,19,21,23,33 knowledge and experience of eating disorders.1,8,9,12,13,22,25,26 The ideal setting for this treatment to take place was in a safe and supportive environment – somewhere that feels ‘like home’,7,11,13,15,21,22,23,27,28,29 considers the individual with eating disorders as a ‘whole person’,7,18,19,29 and offers a ‘collaborative’ approach to treatment7,18,19,21,24,26,27,29,33,41 that is ‘individualised and client-focused’18,19,21,29 offering consultative and directional care.9,11,33

At the same time, the ‘good professional’ needed to remain authoritative, reflecting confidence and professionalism13 and setting meaningful and appropriate treatment goals.17,28 It is suggested that a combination of ‘autonomy and direction’ equals ‘balance and success’ in eating disorder treatment.11 Some professionals also supported this ideal system, suggesting that although eating disorder experience, skill and knowledge are important in the treatment of eating disorders, building strong relationships with individuals with eating disorders and their family/friends, and delivering care holistically can have a greater impact of helpfulness than any type of treatment provided.43,59,61,62

Specialised and/or complex? – So, who's responsible for eating disorders?

One of the issues raised by non-eating disorder specialists was that eating disorders is both specialised and complex in nature.59,61 Eating disorders are considered ‘rare, chronic and require intense care, high levels of treatment and high demand from HPs [health professionals]’.43 Yet, it was regularly argued that eating disorder treatment should reflect its specialist need, and the best place for individuals with eating disorders is in specialist care43 that provides the time and expertise43,61 to build supportive relationships. Similarly, individuals with eating disorders and their family/friends perceived specialist eating disorder care as the ‘best’ or ‘better’ treatment for eating disorders,6,7,10,17,19,24,34,35,37,43 providing better understanding and knowledge of eating disorders,2,3,9,20,25,43 empathy3,9,25 and personal recognition.18 Unsurprisingly, many non-specialist health professionals felt that they ‘should’ or ‘would rather’ refer individuals with eating disorders on to these services,43,55,57 and many individuals with eating disorders and their family/friends wanted this ‘best’ treatment too.6,7,10,17,19,24,34,35,37,43

However, ‘referring on’ often was to under-resourced specialist service struggling to respond to demand.19,25,35,43 Eating disorder services created limited access,21,30,33 geographical barriers,21 long waiting lists and delays,1,19,21,30 rigid admission rules based on single treatment modalities and eating disorder physical traits.21,25,30,33 Lower body mass indexes took priority,26,30 and referrals were only accepted for very serious cases.1,6,21,25,30 Furthermore, specialist eating disorder care provided no guarantee of treatment even after gaining access,30 with the risk of losing a place if another patient took priority25,30 and immediate discharge occurring after weight restoration, with little if any aftercare.30

Eating disorders requires a multidisciplinary approach and team involved, including a range of primary and secondary care professionals,43,53,61 with the inclusion of families.53 However, this multidisciplinary model could suffer misconceptions, such as the assumption of professionals that ‘some treatment is better than none’.43

Out-patient care10,11,35 was favoured by some individuals with eating disorders as allowing a consultative and collaborative approach to treatment control,11 and when delivered by a professional with sufficient eating disorder expertise, family/friends tended to feel that out-patient care is the most beneficial, compared with any other treatment.35 To others, out-patient treatment was an unsuccessful, unsuitable or unskilled option.2,17

Medical general ward admissions were reported by all professionals, individuals with eating disorders and families as the most negative setting for eating disorders and the ‘most inappropriate location’, ‘unsuitable and unhelpful’ for individuals with eating disorders, making them feel isolated and treated by general ward staff who lacked skill and specialist eating disorder knowledge.1,2,4,7,17,34,40,43,48 Professionals working on these medical general wards reported difficulties delivering care to individuals with eating disorders because of their ‘deceitful and non-compliant’ personalities48 and reported a ‘struggle to understand the complex disorder’59 that challenged their nursing values, often causing more harm than good to the patients with eating disorders.48,59

Overall, specialist eating disorder care was considered the gold standard in eating disorder treatment. Unfortunately, this was not only often unobtainable, but emphasis as a ‘best’ care ultimately undermined other agencies, treating them as mere stepping stones to specialised services rather than potentially beneficial alternatives. It appeared to be the characteristics and techniques used – collaborative and patient-centred care that is knowledgeable yet sensitive to issues of control and ambivalence – that determined positive outcomes. Appendix 3 outlines the key points from theme 2.

Theme 3: collaboration versus opposition

The third theme that emerged in the data is collaboration versus opposition in the treatment of eating disorders. This theme had two subthemes. Healthcare should be a partnership between the patient, families and the health professional.6,8,13,14,34,59 However, in the case of eating disorders, a shared partnership in healthcare can often be lacking, with hostility and opposition, the misuse of power relations and a lack of collaborative care.2,6,7,9,11,13,59

The weight versus well-being paradigm

Perceived oppositions between the physical and emotional aspects of eating disorder treatment and recovery were identified. There is an opposition between the ‘rarity’ and ‘recovery’ aspects of eating disorders, as the prospect of recovery from eating disorders is often unknown, underestimated or overestimated among health professionals.44,49,53,56 Anorexia nervosa was sometimes viewed as chronic with no recovery prospects44,49,52,56 whereas the prevalence and severity of bulimia nervosa was greatly underestimated.44,49,53 In contrast, for individuals with eating disorders and their family/friends, the expectation of recovery drove help-seeking and treatment.1,14,16

Another opposition occurred between the professional and family members focusing on the ‘visible signs of eating disorders’ seeing physical status as the most valuable measure of treatment and recovery4,29 as compared with individuals with eating disorders focusing on psychological markers such as improved ‘well-being’ and feeling ‘normal’.1,8,18,20,23,29,30 Overall, this lack of clarity resulted in a weight versus well-being paradigm and constituted a considerable barrier at the eating disorder healthcare interface frequently described by individuals with eating disorders and their family/friends as ‘too much focus on food and weight’,1,2,4,7,15,19,23,25,29,30,35,40 reported in both primary and secondary care.30 There is further conflation of completion of treatment with recovery,52,54 with professionals measuring outcomes based on ‘completion’ of treatment, whereas individuals with eating disorders felt recovery should be based on ‘doing well’.53

Power relations versus collaboration

Oppositions existing within the weight versus well-being paradigm were also reported as part of a ‘power system’4,8,30 throughout the eating disorder pathway, to the detriment of good practice.8 Early in help-seeking and diagnosis, the overemphasis on ‘weight and food’ triggered a ‘drive’, because to ‘eat less food and lose more weight’ won individuals priority for treatment in specialist eating disorder services.30 However, once entry was gained to eating disorder services, opposition between individuals with eating disorders and professionals continued, with healthcare professionals (for example secondary care staff in an in-patient unit) attempting to ‘hold all the power’.4 Some in-patient units used ‘reward systems’ based on penalties and privileges,8,15,33 making individuals with eating disorders feel that professionals ‘take all the power’.15

For some individuals with eating disorders, specialist eating disorder treatment was considered ineffective as this undermined engagement4,7 leaving them disempowered4 distressed1,17,18,25,29 and patronised,7,33 in a system that was too restrictive, structured and strict.18,21,23 This resulted in loss of personal control, identity and normality.1,2,7,8,15,17,19 Some individuals with eating disorders described these battles as triggering power systems, where rigid rules and unfair power relations forced individuals with eating disorders to become rebellious or deceitful, compelling them to ‘put on an act’23 as the ‘perfect patient’8 to comply, resulting in an opposing identity of the rebel.27 This is reported as being detrimental to the health and recovery of the person with eating disorders23,27 as it entrenched eating disorder symptoms and increased vulnerability.17,29 For other individuals with eating disorders, restrictive treatment could be a ‘safe haven’.18 The loss of control and normality were considered positive1,9,15,17,18 because it helped set boundaries and relinquish control,15,33 relieving individuals of responsibility and allowing them to regain control ‘elsewhere’ as treatment progresses.18 However, regaining control was problematic after discharge, especially if there was little aftercare.15,16,17,29

Professionals (for example secondary care staff in an in-patient unit) felt that too much authoritative control in the eating disorder treatment settings caused considerable stress for people with eating disorders and their families62 and obstructed trusting relationships, causing rebellious outbursts among those with eating disorders.59 For professionals, judiciously managing control was crucial,59,62 without ‘enforcing’ it and triggering ‘power in play’ between the patient with eating disorders and professionals with resultant ‘mutual mistrust’.48,59 Family and friends of individuals with eating disorders reflected that shifting their role in the home ‘from power and authority to one of support and encouragement’ improved outcomes.41 Family and friends felt all sides should work together as a team36 ‘on the same page’,41 with all affected by eating disorders mutually involved in treatment and the recovery process.36,41 Therefore, it was important to not remove all control and power from those affected by eating disorders11 and professionals should adopt directional not authoritative stances9 and be firm yet consistent.15 In eating disorders, if power relations were distributed more fairly in the eating disorder care setting, the ultimate wish of all parties for more room for greater collaboration in eating disorder treatment would result.18,21,39,41 Appendix 4 outlines the key points from theme 3.

Figure 2 outlines the key points in a diagram format of the three dominant themes and their additional subthemes

Fig. 2.

Summary of themes.

Discussion

Main findings

This review provides an overview of the facilitators and barriers existing at the current eating disorder healthcare interface from a range of perspectives and experiences. Overall, the initial blame and responsibility for existing barriers tends to fall on professionals in primary care. Many individuals with eating disorders and their families/friends view primary care as a gateway to access more specialised services, rather than seeing primary care professionals as sources of help for eating disorders. However, for primary care professionals this acts as a double-bind as they are variously held responsible by all parties for failing to be knowledgeable, treating insufficiently or referring on too readily or inappropriately, reducing their sense of professional competency. In summary, primary care professionals would benefit from more understanding of the needs of both individuals with eating disorders and their families/friends, and how to neither over- nor under-refer. The analysis suggests that rather than just being a gateway to specialist care, primary care professionals can and should play a crucial role in engaging ambivalent in individuals with eating disorders while supporting and advising families/friends in promoting recovery.

It may be important to challenge the gold-standard expectation attached to specialist eating disorder care, as its current status in the eyes of individuals with eating disorders, their families and health professionals as the ‘best’ ultimately undermines all other services, dismissing primary care as a mere conduit, when it could potentially be a better alternative for some. This would require more training and support for primary care professionals to address their anxieties and difficulties in diagnosing, treating and supporting people with eating disorders. Specialist services need to be more responsive to primary care and improve shared care across the primary–secondary care interface for eating disorders. For example, as previously discussed in the background section of this paper, GPs in particular currently feel unequipped to identify and manage an eating disorder and prefer to pass the patient on to specialist services.8 But, as this review suggests, if primary care were better supported by specialist services, they would feel more confident in their professional ability to work with patients with eating disorders.

The review suggests a complex function of the primary–secondary interface found in current eating disorder healthcare. This review adds to the knowledge-base and provides recommendations for moving forward in research and practice, these are in line with the generally accepted principles and values to deliver a better integrated service for all with shared partnerships and mutual responsibility.

The tensions identified in the final theme of collaboration versus opposition in the treatment of eating disorders are familiar. What is less familiar is the exploration of how this has an impact on the primary–secondary healthcare interface. The issues of power differentials and use of authority and control has ramifications when patients are discharged before they wish to be, or when medical responsibility is handed back to primary care. It is not clear in this review how the alterations in balance between collaboration and authoritativeness or emphases on weight versus well-being are negotiated between specialist and primary care professionals, and this is an area for further research.

The geographic locations of the included papers were higher-income countries; it would be important to examine middle- or lower-income countries in future research. Furthermore, despite a 20-year publication range, there was consistency of themes across all papers, which suggests that little has been done in the past two decades to address these reported problems. Therefore, work is needed to address difficulties with the primary–secondary care interface for eating disorder services.

Recommendations for an improved eating disorder service

Based on our research our recommendations are as follows.

More training and support for professionals is needed across the interface, especially in primary care settings to address the anxieties and difficulties in diagnosing and treating eating disorders.

Primary care professionals would benefit from more understanding of the needs of both individuals with eating disorders and family/friends, and how to neither over- nor under-refer.

While being a gateway to specialist care, primary care professionals need to better engage with and support individuals with eating disorders and their families/friends between waiting times and referrals.

It may be important to challenge the gold-standard ‘best’ expectation that is attached to specialist eating disorder care, as it may be undermining other services.

The ‘ideal’ vision of an eating disorder professional, setting and technique may be someone/something that can be used as a ‘good practice’ template.

It is important to link up services across the interface, adopting a multidisciplinary, shared-care approach.

This ‘linked up’ approach would require services across the interface to be more responsive to each other and upskill a range of professionals to fit the ‘ideal’ and ‘best’ care vision of services.

More collaborative understanding of eating disorders and mutual partnerships is needed across the primary–secondary interface to avoid the use of power and control, resulting in hostility and mistrust between partnerships.

More research is needed in this area to address the difficulties and challenges within the primary–secondary interface for eating disorder services.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review has identified many areas for improvement in clinical practice, and its findings can lead to concrete recommendations. The strengths of this study are the wide range of perspectives and experiences analysed from three groups of people, including people with eating disorders, families and health professionals across international healthcare systems. The limitations for this review are the lack of primary papers available focusing principally and/or specifically on the facilitators and gaps at the interface. As a result, these findings were gleaned from papers that had a main focus elsewhere. To ensure greater in-depth analysis of the data, a much larger set of primary data would be required.

In conclusion, this systematic review looks at a range of experiences and perspectives of the eating disorder primary and secondary care healthcare interface. Three dominant themes of ‘the help-seeking process at primary care’, ‘expectations of care and appropriate referrals’ and ‘opposition and collaboration in treatment of and recovery from eating disorders’ identify many facilitators and barriers existing at the interface. We suggest that attention to these issues could improve the quality of care and experiences of individuals with eating disorders and their families and the role of health professionals.

Appendix 1

Study eligibility checklist

| Inclusion |

| Studies employing both qualitative or quantitative methodology or mixed design primary studies. |

| Studies specifically focusing on eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder or eating disorders not otherwise specified). |

Populations of:

|

| Settings including: |

|

| Studies with a focus of perspectives or experiences of eating disorder healthcare. |

| No restrictions on date of publication or geographic location. |

| Exclusion |

| Non-English studies. |

| Secondary studies (for example reviews). |

Appendix 2

Key point summary theme 1

| Primary care |

Individuals with eating disorders/families’ view:

|

Health professionals’ view:

|

Utilising the primary setting:

|

Appendix 3

Key point summary theme 2

| Primary care versus secondary care |

The ideal service for individuals with eating disorders and family/friends:

|

Specialist versus complexity of eating disorders:

|

Appendix 4

Key point summary theme 3

The eating disorder healthcare interface

|

Funding

This systematic review is part of a research project entitled ‘Mind the Gap! An examination of the interface between primary and secondary healthcare for eating disorders’. This work was supported by the Welsh Government through Health and Care Research Wales (HRA grant number: HRA-15-1079).

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.48.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1.Keel PK, Brown TA. Update, course and outcome in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2010; 43: 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay PJ, Mond JM. How to count the cost and measure burden? A review of health-related quality of life in people with eating disorders. J Ment Health 2005; 14: 539–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crow SJ, Swanson SA, Raymond NC, Specker S, Eckert ED, Mitchell JE. Increased mortality in bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166: 1342–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zipfel S, Giel KE, Bulik CM, Hay P, Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2: 1099–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grave RD. Eating disorders: progress and challenges. Eur J Intern Med 2011; 22: 153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tierney S. Perspectives on Living with an Eating Disorders: Lessons for Clinicians. In Eating and its Disorders (eds Goss JRE and Fox KP): 117–33. John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampson R, Cooper J, Barbour R, Polson R, Wilson P. Patients’ perspectives on the medical primary–secondary care interface: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Br Med J 2018; 5: e008708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke D, Polimeni-Walker I. Treating individuals for eating disorders in family practice. A need for assessment. Eat Disord 2004; 12: 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waller G, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Marray K, Aleyna J, Emanuelli F, et al. Problems across care pathways in specialist adult eating disorder services. Psychiatr Bull 2009; 33: 26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.BEAT. Beat Eating Disorder Charity: Statistics for Journalists. How Many People in the UK have an Eating Disorder? BEAT, 2018. (https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/media-centre/eating-disorder-statistics). [Google Scholar]

- 11.PHW. Report on a Review of the Eating Disorders Framework for Wales. Public Health Wales, 2016. (http://gov.wales/docs/dhss/publications/160824eating-disorderen.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS England. Principles and Values that Guide the NHS. NHS Choices, 2018. (https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/thenhs/about/Pages/nhscoreprinciples.aspx). [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS Scotland. Realising Realistic Medicine. Scottish Government, 2017. (https://beta.gov.scot/news/realising-realistic-medicine/). [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Wales. Achieving Prudent Health in NHS Wales. Public Health Wales, 2014. (http://www.1000livesplus.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/1011/Achieving%20prudent%20healthcare%20in%20NHS%20Wales%20paper%20Revised%20version%20%28FINAL%29.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prudent Healthcare. Making Prudent Healthcare Happen. Prudent Healthcare, 2014. (http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/866/PHW%20Prudent%20Healthcare%20Booklet%20Final%20English.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell GK, Burridge L, Zhang J, Donald M, Scott IA, Dart J, et al. Systematic review of integrated models of healthcare delivered at the primary-secondary interface: how effective is it, and what determines effectiveness. Aust J Prim Care 2015; 21: 391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Institute of Health Research, Lancaster, 2006. (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.178.3100&rep=rep1&type=pdf).

- 19.Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojikova M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development, policy and practice. J Dev Effect 2012; 4: 409–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP, 2017(https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tierney S. The individual within a condition: a qualitative study of young people's reflections of being treated for anorexia nervosa. Am Psychiatr Nurs Assoc 2008; 13: 368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rie SDL, Noordenbos G, Donker M, Furth DV. Evaluating the treatment of eating disorders from the patient perspective. Int J Eat Disord 2006; 39: 667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinton D, Almlof L, Lindstrom S, Manneberg M, Vestin L. Drop-in access to specialist services for eating disorders: a qualitative study of patient experiences. Eat Disord 2014; 22: 279–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linville D, Brown T, Strum K, McDougal T. Eating disorders and social support: perspectives of recovered individuals. Eat Disord 2012; 20: 216–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson KJ, Mountford VA, Sperlinger DJ. Being men with eating disorders: perspectives of male eating disorder service-users. J Health Psychol 2012; 18: 176–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bravender T, Elkus H, Lange H. Inpatient medical stabilization for adolescents with eating disorders: patient and parent perspectives. Eat Weight Disord 2016; 22: 483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheridan G, McArdle S. Exploring patient's experiences of eating disorder treatment services from a motivational perspective. Qual Health Res 2016; 26: 1988–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boughtwood D, Halse C. Other than obedient girls: constructions of doctors and treatment regimes for anorexia nervosa. J Commun Appl Soc Psychol 2010; 20: 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Ommen J, Meerwijk EL, Kars M, Elburg AV, Meijel BV. Effective nursing care of adolescents diagnosed with anorexia nervosa: the patients’ perspective. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 2801–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenvinge JH, Klusmeier AK. Treatment for eating disorders from a patient satisfaction perspective: a Norwegian replication of a British study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2000; 8: 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid M, Burr J, Williams S, Hammersley R. Eating disorder patients views in their disorders and an outpatient service: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol 2008; 13: 956–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulliksen KS, Nordbo RHS, Espeset EMS, Skarderud F, Holte A. The process of help-seeking in anorexia nervosa: patients’ perspective of first contact with health services. Eat Disord 2015; 23: 206–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulliksen KS, Epeset EMS, Nordbo RHS, Skarderud F, Geller J, Holte A. Preferred therapist characteristics in treatment of anorexia nervosa: the patient perspective. Int J Eat Disord 2012; 45: 932–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson K, Hagglof B. Patient perspective of recovery in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord 2006; 14: 305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zugai J, Stein-Parbury J, Roche M. Effective nursing care of adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a consumer perspective. J Clin Nurs 2013; 22: 2020–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Federici A, Kaplan AS. The patient's account of relapse and recovery in anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2008; 16: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox JRE, Diab P. An exploration of the perceptions and experiences of living with chronic anorexia nervosa while an inpatient on an eating disorder unit: an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) study. J Health Psychol 2015; 20: 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith V, Chouliara Z, Morris PG, Collin P, Power K, Yellowlees A, et al. The experiences of specialist inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study from adult patient perspectives. J Health Psychol 2016; 21: 16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Escobar-Koch T, Banker JD, Crow S, Ringwood S, Smith G, Furth EV, et al. Service users’ views of eating disorder services: an international comparison. Int J Eat Disord 2010; 43: 549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swain-Campbell NR, Surgenor LJ, Snell DL. An analysis of consumer perspectives following contact with an eating disorder service. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001; 35: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimitropoulos G, Toulany A, Herschman J, Kovacs A, Steinegger C, Bardsley J, et al. A qualitative study of the experiences of young adults with eating disorders transferring from paediatric to adult care. Eat Disord 2015; 23: 144–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen G, Rosenvinge JH. Improvement and recovery from eating disorders: a patient perspective. Eat Disord 2002; 10: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grange DL, Gelman T. Patient perspectives of treatment in eating disorders: a preliminary study. S Afr J Psychol 1998; 28: 182–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindstedt K, Neander K, Gustafsson A. Being me and being us - adolescent experiences of treatment for eating disorders. J Eat Disord 2015; 3: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker S, Lloyd C. Issues experienced by service users with an eating disorder: a qualitative investigation. Int J Ther Rehabil 2011; 18: 542–51. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paulson-Karlsson G, Nevonen L. Anorexia nervosa: treatment expectations - a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2012; 5: 169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colton A, Pistrang N. Adolescents’ experiences of inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2004; 12: 307–16. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaitsoff S, Pullmer R, Menna R, Geller J. A qualitative analysis of aspects of treatment that adolescents with anorexia identify as useful. Psychiatry Res 2016; 238: 251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Offord A, Turner H, Cooper M. Adolescent inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study exploring young adult's retrospective views of treatment and discharge. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2006; 14: 377–87. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rance N, Moller NP, Clarke V. Eating disorders are not about food, they're about life: client perspectives on anorexia nervosa treatment. J Health Psychol 2015; 22: 582–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clinton D, Bjork C, Sohlberg S, Norring C. Patient satisfaction with treatment in eating disorders: cause for complacency or concern? Eur Eat Disord Rev 2004; 12: 240–6. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schoen EG, Lee S, Skow C, Greenberg ST, Bell AS, Wiese JE, et al. A retrospective look at the internal help-seeking process in young women with eating disorders. Eat Disord 2012; 20: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans EJ, Hat PJ, Mond J, Paxton SJ, Quirk F, Rodgers B, et al. Barriers to help-seeking in young women with eating disorders: a qualitative exploration in a longitudinal community survey. Eat Disord 2011; 19: 270–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halvorsen I, Heyerdahl S. Treatment perception in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa: retrospective views of patients and parents. Int J Eat Disord 2007; 40: 629–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roots P, Rowlands L, Gowers SG. User satisfaction with services in a randomised controlled trail of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Eur J Eat Disord 2009; 17: 331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McMaster R, Beale B, Hillege S, Nagy S. The parent experience of eating disorders: interactions with health professionals. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2004; 13: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winn S, Perkins S, Murray J, Murphy R, Schmidt U. A qualitative study of the experience of caring for a person with bulimia nervosa. Part 2: carers’ needs and experiences of services and other support. Int J Eat Disord 2004; 36: 269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCormack C, McCann E. Caring for an adolescent with anorexia nervosa: parents views and experiences. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2015; 29: 143–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Honey A, Boughtwood D, Clarke H, Kohn M, Madden S. Support for parents of children with anorexia: what parents want. Eat Disord 2008; 16: 40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tierney S. The treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study of the views of parents. Eat Disord 2005; 13: 369–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cohn L. Parents voices: what they say is important in the treatment and recovery process. Eat Disord 2005; 13: 419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haigh R, Treasure J. Investigating the needs of carers in the area of eating disorders: development of the carers needs assessment measure (CaNAM). Eur Eat Disord Rev 2003; 11: 125–41. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reid M, Williams S, Burr J. Perspectives on eating disorders and service provision: a qualitative study of healthcare professionals. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2010; 18: 390–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Currin L, Walker G, Schmidt U. Primary care physician's knowledge of and attitudes toward the eating disorders: do they affect clinical actions. Int J Eat Disord 2009; 42: 453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bannatyne AJ, Stapleton PB. Attitudes towards anorexia nervosa: volitional stigma differences in a sample of pre-clinical medicine and psychology students. J Ment Health 2017; 26: 442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burket RC, Schramm LL. Therapists attitudes about treating patients with eating disorders. Southern Med J 1995; 88: 813–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boule CJ, McSherry JA. Patients with eating disorders: how well are family physicians managing them? Can Fam Phys 2002; 48: 1807–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.King SJ, Turner SD. Caring for adolescent females with anorexia nervosa: registered nurses’ perspectives. J Adv Nurs 2000; 32: 139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Linville D, Benton A, O'Neil M, Strum K. Medical providers screening, training, and intervention practices for eating disorders. Eat Disord 2010; 18: 110–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Linville D, Brown T, O'Neil M. Medical providers self-perceived knowledge and skills for working with eating disorders: a national survey. Eat Disord 2012; 20: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker S, Lloyd C. Barriers and attitudes health professionals working in eating disorders experience. Int J Ther Rehabil 2011; 18: 383–91. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vanderlinden J, Buis H, Pieters G, Probst M. Which elements in the treatment of eating disorders are necessary ‘ingredients’ in the recovery process? A comparison between the patients and therapist's views. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2007; 15: 357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jones WR, Saeidi S, Morgan JF. Knowledge and attitudes of psychiatrists towards eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2013; 21: 84–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Masson PC, Sheeshka JD. Clinicians perspectives on the premature termination of treatment in patients with eating disorders. Eat Disord 2009; 17: 109–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnston O, Fornai G, Cabrini S, Kendrick T. Feasibility and acceptability of screening for eating disorders in primary care. Fam Pract 2007; 24: 511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anderson K, Accurso EC, Kinasz KR, Grange DL. Residents and fellow's knowledge and attitudes about eating disorder at an academic medical centre. Acad Psychiatry 201. 7; 41: 381–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Banas DA, Redfern R, Wanjiku S, Lazebnik R, Rome ES. Eating disorder training and attitudes among primary care residents. Clin Paediatr 2013; 52: 355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johansson AK, Johansson A, Nohlet E, Norring C, Astrom AN, Tegelberg A. Eating disorders - knowledge, attitudes, management, and clinical experience of Norwegian dentists. BMC Oral Health 2015; 15: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramjam LM. Nurses and the therapeutic relationship: caring for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Adv Nurs 2004; 45: 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Girz L, Robinson AL, Tessier C. Is the next generation of physicians adequately prepared to diagnose and treat eating disorders in children and adolescents? Eat Disord 2014; 22: 375–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hay P, Darby A, Mond J. Knowledge and beliefs about bulimia nervosa and its treatment: a comparative study of three disciplines. J Clin Psychol Med 2007; 14: 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ryan V, Malson H, Clarke S, Anderson G, Kohn M. Discursive constructions of eating disorders nursing. an analysis of nurses’ accounts of nursing eating disorder patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2006; 14: 125–35. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hunt D, Churchill R. Diagnosing and managing anorexia nervosa in UK primary care: a focus group study. Fam Pract 2013; 30: 459–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.48.

click here to view supplementary material