Abstract

Background

Many older adults are homebound due to chronic illness and suffer from significant symptoms, including pain. Home-based primary and palliative care (HBPC), which provides interdisciplinary medical and psychosocial care for this population, has been shown to significantly reduce symptom burden. However, little is known about how pain is managed in the homebound.

Objective

This article describes pain management for chronically, ill homebound adults in a model, urban HBPC program.

Design/Measurements

This was a prospective observational cohort study of newly enrolled HBPC patients, who completed a baseline Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) survey during the initial HBPC visit (N = 86). Baseline pain burden was captured by ESAS and pain severity was categorized as none, mild, or moderate-severe. All pain-related assessments and treatments over a 6-month period were categorized by medication type and titration, referrals to outside providers, procedures, and equipment.

Results

At baseline, 55% of the study population had no pain, 18% had mild pain, and 27% had moderate-severe pain. For those with moderate-severe pain at baseline (n = 23), prescriptions for pharmacological treatments for pain, such as opiates and acetaminophen, increased during the study period from 48% to 57% and 52% to 91%, respectively. Nonpharmacological interventions, including referrals to outside providers such as physical therapy, procedures, and equipment for pain management, were also common and 67% of the study population received a service referral during the follow-up period.

Conclusions

Pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments are widely used in the setting of HBPC to treat the pain of homebound, older adults.

Keywords: home-based primary and palliative care, pain management, homebound

Introduction

In increasing numbers of older adults, multiple chronic health conditions result in functional impairment, substantial symptom burden, and homebound status.1–3 These individuals, who comprise nearly 6% of adults aged 65 and older in the United States, are more likely to have health-care needs requiring hospitalization, cognitive impairment, and increased mortality rates compared to nonhomebound individuals.4–6

Compounding the vulnerability of this population is limited access to quality health care in the home.7 Home-based primary and palliative care (HBPC) provides much needed access to medical and psychosocial care for this population. This model of care provides multidisciplinary management of complex medical conditions, while at the same time promoting function and independence.2,8

Previous research has demonstrated that HBPC significantly reduces overall symptom burden in chronically ill homebound adults.9 Pain is one of the most common and distressing symptoms experienced by older adults and is associated with increasing frailty.10–15 However, little is known about how specific symptoms, like pain, are assessed and managed in this population. Given recent national efforts to create quality standards for HBPC,16 we sought to describe pain levels and pain management in a model HBPC program. We hypothesized that both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions would be used to manage pain in the home.

Methods

Setting

This 6-month prospective, observational cohort study was conducted at the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors (MSVD) program at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. Mount Sinai visiting doctors, which has been described previously,17 provides HBPC to over 1,500 community dwelling adults annually, most of whom are over 80 and have multiple, serious illnesses. Eligible patients, who are seen every two months, must fulfill the Medicare homebound definition: leaving home requires considerable effort and assistance and is not recommended due to health conditions. The program employs 14 physicians, two nurse practitioners, two nurses, three social workers, and four clerical staff. The MSVD program prioritizes quality of life, comfort, and aims to reduce unnecessary medical interventions and hospitalizations.

Patients

All newly admitted MSVD patients proficient in English, who completed a baseline Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)18 survey by self or proxy, between January 2013 and January 2014 (n = 221) were eligible for the study. All patients who did not complete a baseline ESAS (n = 111, 52%) were excluded. The most common reasons the baseline ESAS was not completed were advanced dementia and nonverbal status. Eight (3%) patients refused to participate. Of those 104 patients who completed a baseline ESAS and were available to participate in the study, 12(11%) declined further participation and six (5%) were lost to follow-up (Supplemental Figure 1).

Measures

The primary measure of interest in this study is the ESAS pain assessment. Symptom severity was ranked as 0 = none, 1 to 3 = mild, and 4 to 10 = moderate-severe. The ESAS was selected to assess symptom severity because it has been validated in multiple care settings and has been used previously in the MSVD population.3,9,19

The MSVD physicians further evaluated patient function with the palliative performance scale (PPS) and the activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living scales.20–22 Patient comorbidity was quantified with the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score, which was calculated using the diagnoses included in the electronic medical record (EMR) problem list.23

Data Collection

The baseline ESAS was administered by the MSVD physician during the initial home visit and completed by patient or proxy. All interventions and diagnoses were extracted from the EMR monthly and verified by MSVD physician review. Baseline was defined as the interventions in place at the end of the initial home visit (including medications prescribed prior to MSVD enrollment that were left in place), and follow-up was defined as the cumulative interventions at the end of the 6-month study period.

Interventions for pain were further classified by pharmacological treatments: type, initiations, discontinuations, and titrations, and by nonpharmacological treatments. Categories of pharmacological treatments included acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), lidocaine (patch/gel), adjuvant therapy, and opioids. Medications were identified based on a comprehensive list (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Categories of nonpharmacological treatments included referrals to providers outside of MSVD, procedures, equipment, and nursing visits related to pain.

Analysis

Rates and frequency of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments were calculated at baseline and follow-up. Overall differences between patients with moderate-severe baseline pain compared to all others were assessed by the χ2 test of association and the Mann-Whitney U test. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai institutional review board approved this study protocol.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between January 2013 and January 2014, 221 individuals were newly enrolled in the MSVD program, and 86 consented to participate in the study. Of the 86 participants, the majority was female (n = 63, 73%), white (n = 42, 49%), and over age 70 (n = 78, 91%), with considerable disease burden: 37% (n = 32) had a CCI score ≥3 and 10% (n = 9) had a PPS score 0 to 30, indicating poor prognosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Receiving HBPC According to Baseline Pain Score.

| Characteristic | None-Mild Pain, n (%; n = 63) | Moderate-Severe Pain, n (%; n = 23) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 41 (65) | 22 (96) | .005 |

| Ethnicity | White | 32 (51) | 10 (43) | .55 |

| Nonwhitea | 31 (49) | 13 (57) | ||

| Age | ≤69 | 6 (10) | 2 (9) | .97 |

| 70–79 | 6 (10) | 2 (9) | ||

| 80–89 | 22 (35) | 7 (30) | ||

| ≥90 | 29 (46) | l2 (52) | ||

| Median length of follow-up, days (range) | 183 (54–183) | 183 (20–183) | .51 | |

| Died during study follow-up | 7 (11) | 2 (9) | 1.0 | |

| Insurance | Has Medicaid | 25 (40) | l0 (43) | .75 |

| Diagnosis | Joint painb | 22 (35) | 11 (48) | .28 |

| Other musculoskeletal painc | 22 (35) | l8 (78) | <.001 | |

| Neurological paind | 9 (14) | 4 (17) | .74 | |

| CHF | 11 (18) | 7 (30) | .19 | |

| History of stroke | 17 (27) | 7 (30) | .75 | |

| Cancer | 7 (11) | 2 (9) | 1.0 | |

| COPD | 4 (6) | 4 (17) | 0.20 | |

| Dementia | 29 (46) | 6 (26) | .10 | |

| Activities of daily living (1–22) | 1–7, most dependent | 8 (13) | 4 (17) | .81 |

| 8–14 | l4 (22) | 4 (17) | ||

| 15–22, most independent | 32 (51) | 13 (57) | ||

| Missing | 9 (14) | 2 (9) | ||

| Independent activities of daily living (1–27) | ≤14 | 45 (71) | l7 (74) | .81 |

| 15–22 | 8 (13) | 3 (13) | ||

| 23–27 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | ||

| Missing | 9 (14) | 2 (9) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index score | 0 | 12 (19) | 4 (17) | .80 |

| 1 | l8 (29) | 7 (30) | ||

| 2 | 9 (14) | 4 (17) | ||

| 3 | 9 (14) | 5 (22) | ||

| 4≥ | l5 (24) | 3 (13) | ||

| Palliative performance scale (0–100) | 10–30 | 6 (10) | 3 (13) | .61 |

| 40–60 | 44 (70) | l7 (74) | ||

| 70–100 | 4 (6) | 2 (9) | ||

| Missing | 9 (14) | 1 (4) |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HBPC, home-based primary and palliative care.

Including black, Latino, and Asian.

Including arthritis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, knee/hip pain, sacroiliitis, degenerative joint disease, and subchondral cystic degenerative changes.

Including back pain, leg pain, shoulder pain, spinal stenosis, vertebral/compression fracture, hip fracture, rib fracture, pelvic fracture, tendonitis, bursitis, adhesive capsulitis of shoulder, calcific tendonitis, vertebral disc herniation, rotator cuff tear, dislocated shoulder, multiple contracted joints, polymyalgia rheumatica, temporomandibular joint dislocation, finger subluxation, and gout.

Including sciatica, neuropathy, radiculopathy, meralgia paresthetica, Charcot Arthropathy, post herpetic neuralgia, and trigeminal neuralgia.

Study participants experienced pain in similar proportions to previously published reports.10,11,24 Nearly half (n = 39, 45%) reported pain at baseline, with 27% (n = 23) having moderate-severe pain and 18% (n = 16) from mild pain. Those with moderate-severe baseline pain were significantly more likely to be female (P < .005), to be prescribed an opioid (P < .001), and have a diagnosis related to musculoskeletal pain, including fractures, spinal stenosis, and tendonitis (P < .001). Notably, the burden of pain associated with joint or musculoskeletal disease was high in the overall population, with 64% (n = 55) of patients carrying an associated diagnosis.

Home-Based Primary and Palliative Care Interventions for Pain

Home-based primary and palliative care providers employed a variety of pharmacological and nonpharmacological pain treatments for all study participants over the course of 6 months (Table 2). By the end of study observation, 58% (n = 50) of all patients had been prescribed acetaminophen, 36% (n = 31) had been prescribed opioids, 33% (n = 28) had been prescribed adjuvants, 21% (n = 18) had been prescribed NSAIDs, and 13% (n = 11) had been prescribed lidocaine.

Table 2.

Pain Treatments Administered Over 6-Month Study Period for Patients Receiving HBPC (N = 86).

| Pharmacological Treatments | n (%) |

| Acetaminophen | 50 (58) |

| Opiates | 31 (36) |

| Adjuvantsa | 28 (33) |

| NSAIDs | 18 (21) |

| Lidocaine | 11 (13) |

| Steroid joint injections | 5 (6) |

| Nonpharmacological treatments | |

| Any referral | 58 (67) |

| Physical therapy | 50 (58) |

| Occupational therapy | 23 (27) |

| Nurse visits | 19 (22) |

| Podiatry | 17 (20) |

| Hospice | 11 (13) |

| Neurology | 4 (5) |

| Orthopedist | 3 (3) |

| Oral surgery | 1 (1) |

| Rheumatology | 1 (1) |

| Pain specialist | 1 (1) |

| Migraine specialist | 1 (1) |

| Any Procedure | 19 (22) |

| X-ray (abdominal, foot, head/neck, hip, leg, knee, shoulder, spine) | 16 (19) |

| CT (abdominal, head, shoulder) | 3 (3) |

| Ultrasound, shoulder | 1 (1) |

| Cerumen disimpaction | 1 (1) |

| Disimpaction | 1 (1) |

| Excision of toe corn | 1 (1) |

| Hydrocortisone suppository | 1 (1) |

| Any equipment | 22 (26) |

| Wheelchair (new, repair, supplies, mobility evaluation) | 17 (20) |

| Brace/splint | 8 (9) |

| Hospital bed (new, repair) | 6 (7) |

| Rollator walker | 1 (1) |

| MSVD urgent pain visits | 19 (22) |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; HBPC, home-based primary and palliative care; MSVD, Mount Sinai visiting doctors; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Partial list includes Gabapentin, Lamotrigine, Nortriptyline, and Baclofen. Full list in the Supplemental Table 1.

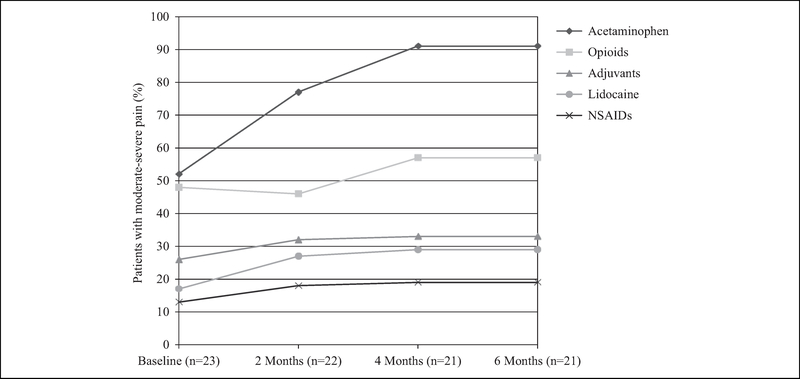

Among those participants with moderate-severe pain at baseline (n = 23), the proportion treated with each category of analgesics increased throughout the study period (Figure 1). Acetaminophen prescriptions nearly doubled from 52% (n = 12) at baseline to 91% (n = 19) at the end of the study period, while prescription of opioids, NSAIDs, lidocaine, and adjuvants rose more modestly. At baseline, nearly half of patients with moderate-severe pain were prescribed opioids (n = 11, 48%). Of these patients, 10 were prescribed a single medication that was primarily short acting (n = 9, 82%), oral (n = 9, 82%), and strong (n = 6, 55%). During the follow-up period, five (45%) of the 11 opioid regimens remained stable, 3 (27%) had dose increases, two (18%) had opioid prescriptions stopped and restarted, and one (9%) had a dose decrease. Of the 12 patients with moderate-severe baseline pain who were not on an opioid at baseline, three (25%) were prescribed an opioid during the study period that was strong, short acting, and either oral (n = 2, 67%) or liquid (n = 1, 33%).

Figure 1.

Pharmacological treatment of pain for patients with moderate-severe baseline pain newly enrolled in home-based primary care at 0, 2, 4, and 6 months.

Home-based primary and palliative care providers frequently employed nonpharmacological interventions to manage pain for the overall study population (Table 2). During the follow-up period, 67% (n = 58) of study participants received a referral to a provider outside of MSVD – including 13% (n = 11) to hospice – 22% (n = 19) underwent a procedure or assessment for pain, and 26% (n = 22) received medical equipment (eg, wheelchair, hospital bed, brace/splint, or rollator walker) to relieve pain or manage functional impairment caused by pain. Additionally, nearly a quarter of the study population (n = 19, 22%) was visited by a MSVD healthcare worker urgently for pain during the study period.

Discussion

Pain is one of the most common and distressing symptoms experienced by older adults. We found that pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments are widely used to manage pain or functional impairment due to pain in homebound adults. Acetaminophen and opioids were the most commonly prescribed medications during the study period, though NSAID prescription was also common, reflecting the high rates of inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions in this population.

Although patients with moderate-severe baseline pain were more likely to be treated with opioids than the rest of the study population, over 40% of these patients were not prescribed an opioid during the study period. Given the high burden of musculoskeletal and joint pain among patients with moderate-severe baseline pain, it is likely that these patients required the relief supplied by anti-inflammatory medications and acetaminophen, the most commonly prescribed drug overall, rather than an opioid. Of note, at the time of this study, the majority MSVD physicians (71%) were board certified in palliative medicine and had extensive training in appropriate opioid use, with the remaining physicians board certified in internal medicine. Furthermore, MSVD has also initiated additional training on opioid prescribing and physicians are now required to complete course work on pain management and addiction by New York State.25

There were several limitations to this study. First, this was a small study from a single, urban HBPC practice, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results. Second, nearly half of the potential study population was excluded primarily because of some form of cognitive impairment, limiting our understanding of pain and pain management in these patients. Third, the treatment data were available only from the start of HBPC enrollment, and there was no way to compare HBPC initiated treatments with those instituted by prior practitioners. It was also not possible to establish the source of a patient’s pain and therefore treatments could not be correlated with specific diagnoses. Additionally, we did not track reasons for changing medications, including any treatment-related complications. Future larger studies should evaluate the types of treatments received before the initiation of home-based primary care, the impact of medication side effects on treatment decision-making, as well as how different interventions affect different etiologies of pain in order to further clarify and enhance treatment recommendations/guidelines for this population. Finally, chart review may be subject to variability in the quality of the information recorded and differences in interpretation. To mitigate these effects, unclear documentation was reviewed with MSVD providers to reach a consensus interpretation. Despite the study’s limitations, we believe it offers valuable insight into current practices surrounding pain management of the homebound elderly.

This work suggests that HBPC providers can identify and manage pain in homebound adults, and that well-trained providers can employ a wide variety of strategies, including opioids, to manage pain in the home. Future work should continue to explore symptom management in the home and the efficacy of specific treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the MSVD Program for their support, and Elizabeth Scott for her assistance in data collection.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a pilot grant through Mount Sinai’s Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center [NIA P30 AG028741-01A2]. Dr Ornstein was supported by the National Institute of Aging [K01 AG047923]. Dr Kelley was supported by the National Institute of Aging [R01AG054540]. Additionally, Hannah Major-Monfried received funding from the AFAR Medical Student Training in Aging Research program to complete this research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

K.O. and A.W. were responsible for the study concept and design. H.M.M. collected study data. K.O. and H.M.M. performed analysis and interpretation of data, and prepared the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and contributed to writing of the article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Qiu WQ, Dean M, Liu T, et al. Physical and mental health of homebound older adults: an overlooked population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12):2423–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck RA, Arizmendi A, Purnell C, Fultz BA, Callahan CM. House calls for seniors: building and sustaining a model of care for homebound seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):1103–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wajnberg A, Ornstein K, Zhang M, Smith KL, Soriano T. Symptom burden in chronically ill homebound individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1180–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of home-bound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12): 2358–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soones T, Federman A, Leff B, Siu AL, Ornstein K. Two-year mortality in homebound older adults: an analysis of the national health and aging trends study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(1): 123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Home Care Medicine. Public policy statement. http://www.aahcm.org/page/Pub_Policy_Statement/Public-Policy-Statement.htm. Accessed September 30, 2017.

- 8.Kellogg FR, Brickner PW. Long-term home health care for the impoverished frail homebound aged: a twenty-seven-year experience. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):1002–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ornstein K, Wajnberg A, Kaye-Kauderer H, et al. Reduction in symptoms for homebound patients receiving home-based primary and palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(9):1048–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel KV, Guralnik JM, Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: findings from the 2011 national health and aging trends study. Pain. 2013; 154(12):2649–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AK, Cenzer IS, Knight SJ, et al. The epidemiology of pain during the last 2 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(9): 563–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shega JW, Dale W, Andrew M, Paice J, Rockwood K, Weiner DK. Persistent pain and frailty: a case for homeostenosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid MC, Eccleston C, Pillemer K. Management of chronic pain in older adults. BMJ. 2015;350:h532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helme RD, Gibson SJ. The epidemiology of pain in elderly people. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17(3):417–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1331–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leff B, Carlson CM, Saliba D, Ritchie C. The invisible home- bound: setting quality-of-care standards for home-based primary and palliative care. Health Aff. 2015;34(1):21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith KL, Ornstein K, Soriano T, Muller D, Boal J. A multidisciplinary program for delivering primary care to the underserved urban homebound: looking back, moving forward. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(8):1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M: Validation of the Edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2164–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. J Palliat Care. 1996;12(1): 5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell CJ, Dalby DM, Slater M, et al. The prevalence and management of current daily pain among older home care clients. Pain. 2008;138(1):208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.New York State Department of Health. Mandatory prescriber education guidance. https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic/docs/mandatory_education_guidance.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.