Abstract

Statins effectively lower low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C), reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Most patients tolerate statins well, but approximately 10% to 20% experience side effects (primarily muscle‐related) contributing to diminished compliance or discontinuation of statin therapy and subsequent increase in cardiovascular risk. Statin‐intolerant patients require more effective therapies for lowering LDL‐C. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is a compelling target for LDL‐C–lowering therapy. Evolocumab (AMG 145) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds PCSK9, inhibiting its interaction with the LDL receptor to preserve LDL‐receptor recycling and reduce LDL‐C. Phase 2 studies have demonstrated the safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of subcutaneous evolocumab in diverse populations, including statin‐intolerant patients. This article describes the rationale and design of the Goal Achievement After Utilizing an anti‐PCSK9 Antibody in Statin‐Intolerant Subjects 2 (GAUSS‐2) trial, a randomized, double‐blind, ezetimibe‐controlled, multicenter phase 3 study to evaluate the effects of 12 weeks of evolocumab 140 mg every 2 weeks or 420 mg every month in statin‐intolerant patients with hypercholesterolemia. Eligible subjects were unable to tolerate effective doses of ≥2 statins because of myalgia, myopathy, myositis, or rhabdomyolysis that resolved with statin discontinuation. The primary objective of the study is to assess the effects of evolocumab on percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C. Secondary objectives include evaluation of safety and tolerability, comparison of the effects of evolocumab vs ezetimibe on absolute change from baseline in LDL‐C, and percentage changes from baseline in other lipids. Recruitment of approximately 300 subjects was completed in August 2013.

Introduction

Statins have shown an overwhelming benefit on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the settings of both primary and secondary prevention.1 For the vast majority of patients, statins are well tolerated and safe to use. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that the incidence of impaired tolerance of statins (generally referred to as statin intolerance) may be much higher than previously reported from randomized controlled trial data.2 In the United States, an estimated 20 million patients are on statin therapy.3 The incidence of statin intolerance may be as high as 10% to 20%.2, 4, 5 Patients with statin intolerance may be unable to tolerate even extremely low doses of statins (eg, half of the lowest starting dose) or unable to tolerate doses adequate to achieve low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) goals. This typically leads to statin discontinuation or patients not achieving their LDL‐C goals, which is associated with higher cardiovascular morbidity.6

Mechanisms of statin‐induced myopathy are unknown and may vary among patients. The development of alternative approaches for lowering LDL‐C may be beneficial for patients who cannot tolerate statins or who do not meet LDL‐C goals at tolerable statin doses. Currently, only moderately effective therapies are available for statin‐intolerant patients. These therapies include bile resins and nicotinic acid, which also are poorly tolerated. Niemann‐Pick C1‐like 1 receptor antagonists such as ezetimibe are generally very well tolerated but usually only yield a 15% reduction of LDL‐C at a dose of 10 mg per day.7

Several therapies currently in development to lower LDL‐C may benefit statin‐intolerant patients, including proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors. PCSK9 is a protein that is involved in the recycling of LDL receptors. Genetic studies have shown that loss‐of‐function mutations in PCSK9 are associated with decreased LDL‐C and lower risk of coronary heart disease.8 Evolocumab (AMG 145) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to PCSK9 and inhibits its interaction with the LDL receptor, resulting in preservation of LDL receptor recycling9 and a subsequent reduction in LDL‐C of approximately 50% to 70% from baseline.10, 11, 12, 13

Recently, several phase 2 studies (efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 as monotherapy in patients with hypercholesterolemia [MENDEL]; efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 in combination with a statin in patients with hypercholesterolemia [LAPLACE‐TIMI 57]; Reduction of LDL‐C with PCSK9 Inhibition in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Disorder [RUTHERFORD]; and Goal Achievement After Utilizing an anti‐PCSK9 Antibody in Statin‐Intolerant Subjects [GAUSS]) demonstrated safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of evolocumab in diverse patient populations.10, 11, 12, 13 In the GAUSS study, a 12‐week, multicenter, global, randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐ and ezetimibe‐controlled, dose‐ranging study in 157 patients who were intolerant of ≥1 statins, subcutaneous (SC) administration of evolocumab was associated with 40% to 60% reduction in LDL‐C, depending on the dose, and was well tolerated. In a 52‐week open‐label extension study of patients with various hypercholesterolemic profiles who had participated in the phase 2 studies, patients who continued treatment with evolocumab sustained a mean 52% reduction in LDL‐C after 1 year.14 This article describes GAUSS‐2, a phase 3 study designed to evaluate the effects of evolocumab compared with ezetimibe in a larger cohort of statin‐intolerant patients with hypercholesterolemia.

Methods

Study Design and Objectives

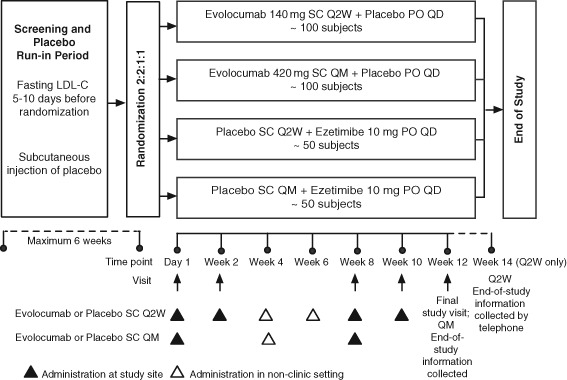

GAUSS‐2 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01763905) is a multicenter, global, randomized, double‐blind, ezetimibe‐controlled study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of evolocumab administered as a SC injection of 140 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) or 420 mg every month (QM) compared with daily ezetimibe (Figure 1). The primary objective of the study is to assess the effects of 12 weeks of therapy on percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C in patients with hypercholesterolemia who are unable to tolerate an effective dose of a statin. Secondary objectives include evaluation of the safety and tolerability of the 2 different dosing regimens in this population; assessment of the effects of evolocumab compared with ezetimibe on absolute change from baseline in LDL‐C; and percentage changes from baseline in high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), lipoprotein (a), non–HDL‐C, very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL‐C), the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL‐C, and the ratio of ApoB to apolipoprotein AI (ApoAI).

Study Population

Subjects were age 18 through 80 years and were not on a statin, or were able to tolerate only a low‐dose statin, as defined in Table 1. They were not at LDL‐C goal for their National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP‐ATP III) risk category (Table 1). Subjects had a history of statin intolerance, defined using a pragmatic, real‐world approach15 based on experience with the GAUSS trial.13 Based on this definition, eligible subjects had tried ≥2 statins and were unable to tolerate any dose or an increase in statin dose above the total maximum doses specified because of intolerable myopathy or myalgia, myositis, or rhabdomyolysis (defined in Table 1), and had their symptoms resolved or improved when the statin dose was decreased or discontinued.5, 13, 15 If subjects were on lipid‐lowering therapies including statins, bile‐acid sequestrants, or stanols, these lipid‐lowering regimens were required to be stable for ≥4 weeks before LDL‐C screening. Ezetimibe had to be discontinued for a washout period of ≥4 weeks before LDL‐C screening. Eligible subjects had a fasting triglyceride level ≤400 mg/dL (4.5 mmol/L) at screening.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

| Age 18–80 years, inclusive |

| Not taking a statin or on a low‐dose statin, defined as a maximum weekly dose of: |

| ≤70 mg atorvastatin |

| ≤140 mg simvastatin, pravastatin, or lovastatin |

| ≤35 mg rosuvastatin |

| ≤280 mg fluvastatin |

| Not at LDL‐C goal per NCEP‐ATP III risk categories for fasting LDL‐C: |

| ≥100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L) for subjects who had CHD or CHD risk equivalent |

| ≥130 mg/dL (3.4 mmol/L) for subjects who did not have diagnosed CHD or risk equivalent but had ≥2 risk factors |

| ≥160 mg/dL (4.1 mmol/L) for subjects who did not have diagnosed CHD or risk equivalent but had 1 risk factor |

| ≥190 mg/dL (4.1 mmol/L) for subjects who did not have diagnosed CHD or risk equivalent and had no risk factors |

| History of statin intolerance, demonstrated by both: |

| Trial of ≥2 statins with intolerance of any dose or to increase statin dose above the total maximum doses because of intolerable: |

| Myopathy or myalgia (muscle pain, ache, or weakness without CK elevation), or |

| Myositis (muscle symptoms with increased CK levels), or |

| Rhabdomyolysis (muscle symptoms with marked CK elevation) and |

| Resolution or improvement of symptoms when the statin dose was decreased or discontinued |

| Stable doses of lipid‐lowering therapies including statins, bile‐acid sequestrants, or stanols for ≥4 weeks before LDL‐C screening |

| Discontinuation of ezetimibe for a washout period of ≥4 weeks before LDL screening |

| Fasting triglyceride level ≤400 mg/dL (4.5 mmol/L) by central laboratory at screening |

| Key Exclusion Criteria |

| Cardiovascular |

| NYHA class III–IV heart failure or last known LVEF <30% |

| Uncontrolled serious cardiac arrhythmia, defined as recurrent and highly symptomatic VT, AF with rapid ventricular response, or SVT that are not controlled by medications, within 3 months prior to randomization |

| MI, UA, PCI, CABG, or stroke within 3 months prior to randomization |

| Planned cardiac surgery or revascularization |

| DM, including: |

| Type 1 DM |

| Type 2 DM that is poorly controlled (HbA1c >8.5%) or newly diagnosed within 6 months before randomization |

| Laboratory evidence of DM during screening (fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dL [7.0 mmol/L] or HbA1c ≥6.5%) without prior DM diagnosis |

| Uncontrolled hypertension, defined as sitting SBP >160 mm Hg or DBP >100 mm Hg |

| Medications |

| Use during the 6 months before LDL‐C screening of red yeast rice, niacin >200 mg/d, prescription lipid‐regulating drugs (eg, fibrates or derivatives) other than statins, ezetimibe, bile‐acid sequestrants, stanols, or stanol esters |

| Use during the 12 months before LDL‐C screening of a CETP inhibitor such as anacetrapib, dalcetrapib, or evacetrapib |

| Use during the 3 months before LDL‐C screening of systemic cyclosporine, systemic steroids excluding HRT, vitamin A derivatives (excluding vitamin A in a multivitamin), or retinol derivatives for the treatment of dermatologic conditions |

| Key Exclusion Criteria |

|---|

| Laboratory values at screening |

| TSH < LLN or >1.5 × ULN |

| eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| CK >3 × ULN |

| AST or ALT >2 × ULN |

| Known concurrent illness within 3 months |

| Infection |

| Major hematologic, renal, metabolic, GI, or endocrine dysfunction in the judgment of the investigator |

| DVT or PE |

| Other |

| Pregnancy, breastfeeding, or inadequate birth control in premenopausal female subjects |

| Previous treatment with evolocumab or any other anti‐PCSK9 therapy |

| Inability to provide informed consent or to attend follow‐up visits |

| Unreliability as a study participant based on judgment of investigator's knowledge of the subject (eg, alcohol or other drug abuse, inability or unwillingness to adhere to the protocol, psychosis) |

| Current enrollment in another investigational device or drug study or <30 d since ending another investigational device or drug study |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHD, coronary heart disease; CK, creatine kinase; CETP, cholesterylester transfer protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; DVT, deep‐vein thrombosis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GI, gastrointestinal; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LLN, lower limit of normal; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NCEP‐ATP III, National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; PE, pulmonary embolism; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; TSH, thyroid‐stimulating hormone; UA, unstable angina; ULN, upper limit of normal; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Subjects were excluded if they had recent acute coronary syndrome, severe heart failure, a recent serious arrhythmia, severe chronic kidney disease, or other medical comorbidities. Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Screening and Enrollment Procedures

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After providing written informed consent, subjects entered a screening period for up to 6 weeks. During this time, those who were taking ezetimibe before enrollment discontinued this medication for ≥4 weeks before LDL‐C screening and were asked to refrain from taking ezetimibe until they either failed screening or were randomized to receive evolocumab or ezetimibe. During the screening period, procedures included collection of medical history and vital signs, review for adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs), concomitant therapy, physical examination, measurement of body height, and 12‐lead electrocardiogram (ECG) using equipment from a centralized ECG service. Blood was drawn for fasting lipids (≥9‐hour fast), chemistry including fasting glucose, hematology, glycated hemoglobin, thyroid‐stimulating hormone, serum pregnancy test (for women of childbearing age), and follicle‐stimulating hormone if required to confirm menopause in women. Blood was also drawn to test for hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies in subjects with a high risk for or a history of HCV infection, or subjects with aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >2× the upper limit of normal (ULN) during screening. A central laboratory analyzed screening and on‐trial blood samples and calculated estimated glomerular filtration rate. Subjects were instructed to maintain current doses of any allowed lipid‐lowering drugs they were taking and counseled on the value of compliance. They were also trained in the use of the autoinjector/pen (AI/pen) for self‐administration of the SC investigational product. To confirm their tolerance of SC administration, all subjects entered a placebo run‐in period before randomization.

After screening, subjects were randomized 2:2:1:1 to 1 of 4 treatment arms (Figure 1): SC evolocumab 140 mg Q2W + daily oral placebo; SC evolocumab 420 mg QM + daily oral placebo; SC placebo Q2W + daily oral ezetimibe 10 mg; and SC placebo QM + daily oral ezetimibe 10 mg. Randomization was stratified by screening LDL‐C concentration (<180 mg/dL [4.7 mmol/L] vs ≥180 mg/dL) and statin use at baseline (yes/no). Subjects, study personnel, and Amgen study staff were blinded to the randomized treatment assignment within schedule groups (Q2W or QM). To maintain blinding, ezetimibe or oral placebo was supplied as over‐encapsulated 10‐mg tablets; unblinding was permitted only when it was essential for management of the subject.

Figure 1.

Schematic of trial design. Subjects successfully completing the screening and placebo run‐in were randomized to one of 4 parallel treatment arms. Subjects attended study visits on day 1 and weeks 2, 8, 10, and 12. Subjects randomized to one of the 2 Q2W treatment arms received study drug every 2 weeks. Subjects randomized to one of the 2 QM treatment arms received study drug every month. Week 12 is the final visit for all subjects. Final end‐of‐study AE and SAE information will be collected at week 12 for the QM arm and by telephone at week 14 for the Q2W arm. Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; PO, oral; Q2W, every 2 weeks; QD, daily; QM, every month; SAE, serious adverse event; SC, subcutaneous.

Treatment Protocol

All doses of evolocumab or SC placebo were administered using the AI/pen. The first treatment of evolocumab or SC placebo was administered at the study site. After administration, subjects remained at the site for observation for ≥30 minutes before being discharged. In the Q2W arm, the week 2, 8, and 10 doses were administered at the study site, and the week 4 and 6 doses were administered in a nonclinic setting by self‐injection. In the QM arm, evolocumab or placebo injections were administered at the study site at week 8 and in a nonclinic setting at week 4. If, in the opinion of an investigator, a subject was unable to tolerate the investigational product, the injections and oral investigational product were discontinued but the subject continued to return to the study site as scheduled for all other study procedures and measurements until the end of the study. Week 12 was the final visit for all subjects. Final end‐of‐study AE and SAE information was collected at week 12 for the QM arm and by telephone at week 14 for the Q2W arm. Compliance with oral dosing was assessed by counting the tablets returned at weeks 2, 8, and 12.

Fasting lipid samples were collected on day 1 and at weeks 2, 8, 10, and 12, before any scheduled administration of evolocumab or placebo. Subjects fasted for ≥9 hours for these assessments. Other assessments conducted from samples collected at study visits included those done at screening and others deemed necessary to ensure subject safety.

Reports from the central laboratory were reviewed before administration of evolocumab or placebo at each visit. If creatine kinase (CK) was ≤5 × ULN, continuation of investigational products was recommended. If CK was >5 × ULN, the subject was retested. If CK was >10 × ULN after retesting, discontinuation of treatment with investigational products was recommended. If CK was between 5 × ULN and 10 × ULN, continuation of investigational products was recommended if there was an alternative explanation. If subjects experienced ALT, AST, or alkaline phosphatase values >3 × ULN and elevated total bilirubin or signs and symptoms of hepatitis, close observation procedures were followed and discontinuation was considered. If subjects had triglyceride values >1000 mg/dL (11.3 mmol/L), investigators were informed so that appropriate subject follow‐up could be initiated. Investigators were asked not to perform nonprotocol laboratory analyses during the study.

Throughout the study, concomitant medications could be prescribed as deemed necessary to provide adequate supportive care, with some exceptions. If used, over‐the‐counter drugs that might alter lipid levels (eg, psyllium preparations such as Metamucil <2 tablespoons per day or plant stanols such as Benecol) had to be stable for ≥4 weeks before LDL‐C screening and to remain constant throughout the study. Treatments prohibited during the study included prescription lipid‐lowering medications other than statins, bile‐acid sequestrants, or stanols and stanol esters; red yeast rice; niacin ≥200 mg per day; or other drugs that affect lipid metabolism (eg, systemic cyclosporine, systemic steroids except for hormone replacement therapy), vitamin A derivatives, and retinol derivatives for dermatologic conditions. Niacin ≤200 mg per day and vitamin A as part of a multivitamin were permitted.

Study Endpoints

The co–primary endpoints of this study are mean percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C at weeks 10 and 12 and percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C at week 12. The LDL‐C value measured by ultracentrifugation was used when calculated LDL‐C was <40 mg/dL or triglycerides were >400 mg/dL. Multiple secondary endpoints, analyzed for both the average of weeks 10 and 12 scores and for week 12 alone, include absolute change from baseline in LDL‐C; LDL‐C response, indicated by the proportion of subjects with LDL‐C <70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L); percentage changes from baseline in ApoB, total cholesterol/HDL‐C, and ApoB/ApoAI; and percentage change from baseline in lipoprotein (a), triglycerides, HDL‐C, and VLDL‐C. Tertiary endpoints include mean percentage change from baseline in ApoAI at weeks 10 and 12 and percentage change from baseline in ApoAI at week 12. Safety endpoints include the number and percentage of subjects who had treatment‐emergent AEs and treatment‐related AEs, safety laboratory values and vital signs, ECG parameters, and incidence of the formation of anti‐evolocumab antibodies (binding and neutralizing). Exploratory safety endpoints include the number and percentage of subjects who had adjudicated cardiovascular events and noncoronary revascularization.

Statistical Design and Analysis

The planned sample size for this study was 300 subjects: 100 in each of the 2 evolocumab/oral placebo arms and 50 in each of the 2 placebo/ezetimibe arms. This sample size provides approximately 92% power at the 2‐sided 0.05 significance level to show the superiority of both evolocumab Q2W and QM over ezetimibe on the co‐primary endpoints (assuming an attenuated treatment effect of 16% for either evolocumab Q2W or QM with an attenuated common SD of 23%).

Efficacy and safety analyses are conducted on all randomized subjects who received ≥1 dose of investigational product. The superiority of evolocumab Q2W or QM over ezetimibe is assessed for all efficacy endpoints. To assess the co‐primary endpoint and the applicable secondary and tertiary efficacy endpoints, a repeated‐measures linear effects model is used in each dose frequency, including terms for treatment group, stratification factors, scheduled visits, and the interaction of treatment with scheduled visit. The secondary efficacy endpoints of LDL‐C response are analyzed using the Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel test adjusted by the stratification factors. Within each dose frequency (Q2W or QM), the multiplicity due to multiple endpoints (co‐primary and secondary efficacy endpoints) is controlled by using sequential testing and the Hochberg approach16 to preserve the familywise error rate at 0.05.

Adverse events are coded using the current version of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Subject incidence of treatment‐emergent AEs, SAEs, and AEs leading to discontinuation of investigational product are reported. Laboratory shift tables for some analytes are prepared using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

Study Organization

An external independent Data Monitoring Committee was established to formally review the accumulating data from this and other ongoing phase III studies of evolocumab to ensure there would be no avoidable increased risk for harm to subjects (Appendix). Analyses for the Data Monitoring Committee were provided by an independent biostatistical group that is external to Amgen. No interim analysis is planned for this study. An independent Clinical Events Committee (Appendix) adjudicated deaths by any cause and specific cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction, hospitalization for unstable angina or heart failure, coronary revascularization, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

Results

Subject recruitment began on January 24, 2013, and was completed on August 29, 2013. A total of 427 subjects were screened, and 307 subjects were randomized into the trial and have received ≥1 dose of investigational product. Baseline characteristics of these subjects are shown in Table 2. Results are based on the data snapshot taken on November 4, 2013.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (N = 307)

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 63 (56–68) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 141 (46) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 287 (94) |

| Asian | 10 (3) |

| Black | 7 (2) |

| Other | 3 (1) |

| Baseline lipid parameters | |

| Screening LDL‐C | |

| Median (IQR), mg/dL | 178 (153–215) |

| <180 mg/dL, n (%)a | 156 (51) |

| ≥180 mg/dL, n (%)a | 151 (49) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 268 (236–307) |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 50 (40–59) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 154 (113–215) |

| Statin‐related history | |

| Statin intolerance, n (%) | |

| 2 | 139 (45) |

| ≥3 | 168 (55) |

| Worst muscle‐related side effect, n (%)b | |

| Myalgiab | 233 (76) |

| Myositisb | 54 (18) |

| Rhabdomyolysisb | 5 (2) |

| Statin use at baseline, n (%)a ,c | |

| Yes | 58 (19) |

| No | 249 (81) |

| Rosuvastatinc | 27 (9) |

| Atorvastatinc | 6 (2) |

| Fluvastatinc | 6 (2) |

| Simvastatinc | 5 (2) |

| Pravastatinc | 5 (2) |

| Other statinsc | 4 (1) |

| Cardiac risk factors | |

| DM, n (%) | 62 (20) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 179 (58) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 24 (8) |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 115 (38) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 28.4 (25.6–31.7) |

| NCEP‐ATP III risk categories, n (%) | |

| High risk | 171 (56) |

| Moderately high risk | 43 (14) |

| Moderate risk | 56 (18) |

| Lower risk | 37 (12) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CK, creatine kinase; DM, diabetes mellitus; IQR, interquartile range; NCEP‐ATP III, National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III.

n = the number of subjects randomized who have received ≥1 dose of investigational product. Results are based on data snapshot taken November 4, 2013.

Stratification factor. b Myopathy or myalgia: muscle pain, ache, or weakness without CK elevation; myositis: muscle symptoms with increased CK levels; rhabdomyolysis (muscle symptoms with marked CK elevation). Baseline data regarding worst muscle‐related side effects were missing for 15 patients (5%). c Statin use at baseline is based on randomization data and individual statins are from case‐report forms; differences between these sources account for differences in the numbers reported.

Discussion

PCSK9 has emerged as an important protein in LDL receptor regulation. PCSK9 binds the LDL receptor and, after internalization, directs the lysosomal degradation of the receptor.17, 18, 19 Thus, overexpression of PCSK9 decreases the number of LDL receptors and leads to an increase in plasma LDL‐C,20 whereas underexpression or reduction of PCSK9 is associated with an increase in LDL receptor number and, consequently, a lower plasma level of LDL‐C.8 Several PSCK9 inhibitors have completed phase 1 and phase 2 studies and have demonstrated promising safety and efficacy.10, 11, 12, 21, 22, 23, 24 These agents lower LDL‐C through a novel mechanism unrelated to 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methyl‐glutaryl‐CoA reductase (HMG‐CoA reductase), which may be particularly beneficial to subjects who are intolerant to lipid lowering by this mechanism of action.

In a pooled analysis of 1359 subjects in 4 phase 2 studies of evolocumab, the incidence of muscle‐related AEs was 6.0% for evolocumab and 3.9% for placebo. One subject who received evolocumab 350 mg every 4 weeks was adjudicated by an independent Clinical Events Committee to have myopathy.25 No cases of myopathy were reported in the 2 phase 1 studies.21 The incidence of muscle‐related AEs will be examined in this study and other phase 3 studies.

The mechanism of myopathy due to statins has not been fully elucidated. However, there appear to be 2 distinct forms of injury, toxic and immune‐mediated. Numerous hypotheses have been proposed regarding mechanisms for toxicity, including cellular hypoprenylation due to the inhibition of HMG‐CoA reductase and the resultant reduction of isoprenoid intermediaries that are involved in numerous signaling pathways, as well as genetic predisposition, mitochondrial toxicity, and statin impairment of calcium transportation in skeletal muscles.26, 27 A genomewide association study in simvastatin‐treated subjects revealed that common genetic variants in SLCO1B1 are associated with considerable alterations in the risk of simvastatin‐induced myopathy.26 These effects were found to be linked to a single‐nucleotide polymorphism in SLCO1B1 causing interference with the transporter to the plasma membrane and resulting in greater systemic statin concentrations.28, 29 Another potential and rare mechanism of myopathic reaction may be related to immune‐mediated factors.30

PCSK9 is not significantly expressed in skeletal muscle, and the mechanism by which PCSK9 inhibition increases the number of cell‐surface LDL receptors is different from the mechanism of the statins, suggesting that PCSK9 inhibition will have potentially few or no myopathic side effects. However, the effect of PCSK9 inhibition on the risk for myopathy remains to be determined from this study and other phase 3 studies (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01763827, NCT01763866, NCT01763918, and NCT01516879).

Though randomized controlled studies show that <5% of subjects had AEs with statin therapy, observational studies have shown that the incidence of statin intolerance in a routine outpatient clinical setting can be as high as 10% to 20% of patients.2, 4, 5 Adverse events are mostly muscle‐related but can also include elevation of ALT and AST and cognitive/memory impairment. The large difference in the reported rates of intolerance between clinical trials and clinical practice may be attributed to the small number of elderly patients and women enrolled in studies as well as routine exclusion of patients with any symptoms or side effects during the run‐in phase of the trial. The presence of a run‐in phase in clinical trials would be expected to lower the rate of statin intolerance observed after randomization. It is also possible that even >20% of patients would be considered statin‐intolerant if counts included individuals who were unable to tolerate a dose high enough to realize the full benefits of statin treatment. Given the high prevalence of statin use, even a conservative estimate of 10% statin intolerance would mean that 2 million patients in the United States are significantly affected by statin side effects. Statin intolerance may lead to diminished patient compliance, reduction of statin doses to ineffective levels, or complete discontinuation of statin therapy. This often results in the unfortunate consequence of an increase in cardiac AEs. To date, there have been limited options to manage this challenging patient population. Ezetimibe is usually well tolerated, but LDL‐C reductions are limited to approximately 15%.7 Mipomersen and lomitapide demonstrated promising reductions in LDL‐C in clinical trials of patients at high cardiovascular risk31, 32; these agents were approved for use only in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and carry warnings of potential liver toxicity.33, 34 Inhibitors of cholesteryl ester transfer protein, such as torcetrapib, dalcetrapib, anacetrapib, and evacetrapib, were considered promising for reduction of cardiovascular risk. Although the development of torcetrapib and dalcetrapib were terminated due to toxicity or lack of efficacy on cardiovascular endpoints, anacetrapib and evacetrapib are currently being evaluated in cardiovascular outcomes studies.36

In GAUSS, 236 patients who were intolerant to ≥1 statins due to muscle‐related side effects were treated for 12 weeks on evolocumab at varying doses. This study showed a 40% to 60% LDL‐C reduction, with 94% of patients completing the study with only minimal side effects. In the GAUSS‐2 study, patients who are intolerant to ≥2 statins were randomized to evolocumab SC 140 mg Q2W or 420 mg QM or to daily ezetimibe. The study population will most likely be a higher‐risk group than GAUSS because GAUSS‐2 requires that patients demonstrate intolerance to ≥2 statins.

For statin‐intolerant individuals, PCSK9 inhibitors offer a therapy that can substantially lower LDL‐C below the levels achieved with currently available nonstatin therapies, thereby providing greater likelihood of achieving LDL‐C treatment goals, potentially with fewer side effects. PCSK9 inhibitors including alirocumab and evolocumab have demonstrated efficacy and tolerability phase 1 and 2 studies,11, 12, 21, 23, 24, 25 including longer‐term use in a 52‐week open‐label extension study.14 Phase 3 studies including GAUSS‐2 for evolocumab are in progress. Results of this and other ongoing phase 3 studies will provide efficacy and safety data for a large population of hypercholesterolemic patients. Additionally, the Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk (FOURIER) study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01764633), with a planned enrollment of >22 000 patients, is designed to evaluate whether PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab improves cardiovascular outcomes for these patients.36 Given the challenges in treating patients with statin intolerance, this new emerging therapy potentially may be a major step forward for LDL‐C reduction in this patient population.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the editorial support of Meera Kodukulla, PhD, of Amgen Inc. and Sue Hudson, BA, on behalf of Amgen.

This trial was supported by Amgen Inc. Leslie Cho has received research funding and consulting fees from Amgen Inc. Michael Rocco has received research funding from Amgen and Eli Lilly, and has received consulting fees from Abbott, Pfizer, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Amarin. David Colquhoun reports no conflict of interest that would be biased to this work. David Sullivan has received research funding from Amgen, Abbott Products, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Sanofi‐Aventis; he has also received funding for educational programs from Abbott Products, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer Australia, and Roche, and travel support from Merck Sharp and Dohme. He served on advisory boards for Abbott Products, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Pfizer Australia. Robert S. Rosenson has served on advisory boards for Abbott, Amgen, LipoScience, Novartis, Sanofi, Regeneron, Sticares, and InterACT and owns stock in LipoScience, Inc. His institution receives research funding on his behalf from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and F. Hoffmann‐LaRoche. Allen Xue, Ricardo Dent, and Scott Wasserman are employees and stockholders of Amgen Inc. Erik Stroes has served on advisory boards for Amgen, Sanofi, Novartis, Merck, Santaris, and Isis Pharmaceuticals.

The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta‐analysis of data from 170 000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, et al. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high‐dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients—the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Topol EJ. The diabetes dilemma for statin users. New York Times March 4, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/05/opinion/the‐diabetes‐dilemma‐for‐statin‐users.html?pagewanted=print. Accessed August 26, 2013.

- 4. Mancini GB, Baker S, Bergeron J, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: proceedings of a Canadian Working Group Consensus Conference. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:635–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:526–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gomez Sandoval YH, Braganza MV, Daskalopoulou SS. Statin discontinuation in high‐risk patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:3669–3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dujovne CA, Ettinger MP, McNeer JF, et al. Efficacy and safety of a potent new selective cholesterol absorption inhibitor, ezetimibe, in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, et al. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan JC, Piper DE, Cao Q, et al. A proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 neutralizing antibody reduces serum cholesterol in mice and nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9820–9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giugliano RP, Desai NR, Kohli P, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 in combination with a statin in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (LAPLACE‐TIMI 57): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging, phase 2 study. Lancet. 2012;380:2007–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koren MJ, Scott R, Kim JB, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 as monotherapy in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (MENDEL): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet. 2012;380:1995–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raal F, Scott R, Somaratne R, et al. Low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol–lowering effects of AMG 145, a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: the Reduction of LDL‐C with PCSK9 Inhibition in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Disorder (RUTHERFORD) randomized trial. Circulation. 2012;126:2408–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sullivan D, Olsson AG, Scott R, et al. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in statin‐intolerant patients: the GAUSS randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2497–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koren MJ, Giugliano RP, Raal FJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of longer‐term administration of evolocumab (AMG 145) in patients with hypercholesterolemia: 52‐week results from the open‐label study of long‐term evaluation against LDL‐C (OSLER) randomized trial. Circulation. 2013; doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.007012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maningat P, Breslow JL. Needed: pragmatic clinical trials for statin‐intolerant patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2250–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. PCSK9: a convertase that coordinates LDL catabolism. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(suppl):S172–S177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qian YW, Schmidt RJ, Zhang Y, et al. Secreted PCSK9 downregulates low‐density lipoprotein receptor through receptor‐mediated endocytosis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1488–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang DW, Lagace TA, Garuti R, et al. Binding of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 to epidermal growth factor‐like repeat A of low‐density lipoprotein receptor decreases receptor recycling and increases degradation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18602–18612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dias CS, Shaywitz AJ, Wasserman SM, et al. Effects of AMG 145 on low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: results from 2 randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers and hypercholesterolemic subjects on statins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1888–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McKenney JM, Koren MJ, Kereiakes DJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease, SAR236553/REGN727, in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing stable atorvastatin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2344–2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roth EM, McKenney JM, Hanotin C, et al. Atorvastatin with or without an antibody to PCSK9 in primary hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1891–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stein EA, Mellis S, Yancopoulos GD, et al. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1108–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raal F, Giugliano RP, Koren MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of AMG 145, a fully human monoclonal antibody to PCSK9: data from four phase 2 studies in over 1200 patients. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7:278 (Abstract 170). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, et al; Search Collaborative Group . SLCO1B1 variants and statin‐induced myopathy—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:789–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Voora D, Shah SH, Spasojevic I, et al. The SLCO1B1*5 genetic variant is associated with statin‐induced side effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1609–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hermann M, Bogsrud MP, Molden E, et al. Exposure of atorvastatin is unchanged but lactone and acid metabolites are increased several‐fold in patients with atorvastatin‐induced myopathy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kameyama Y, Yamashita K, Kobayashi K, et al. Functional characterization of SLCO1B1 (OATP‐C) variants, SLCO1B1*5, SLCO1B1*15 and SLCO1B1*15 + C1007G, by using transient expression systems of HeLa and HEK293 cells. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher‐Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin‐associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:713–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cuchel M, Meagher EA, du Toit Theron H, et al. Efficacy and safety of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a single‐arm, open‐label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2013;381:40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Visser ME, Wagener G, Baker BF, et al. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, lowers low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in high‐risk statin‐intolerant patients: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1142–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Juxtapid (lomitapide) tablets [US full prescribing information]. Cambridge, MA: Aegerion Pharmaceuticals Inc. December 2012. Available at: http://www.aegerion.com/Collateral/Documents/English‐US/R3_JuxtapidCombinationPI_QC_21Dec12%20pdf%20pdf.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2013.

- 34.Kynamro (mipomersen sodium) injection [US full prescribing information]. Cambridge, MA: Genzyme Corporation. January 2013. Available at: http://www.kynamro.com/∼/media/Kynamro/Files/KYNAMRO‐PI.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2013.

- 35. Schaefer EJ. Effects of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors on human lipoprotein metabolism: why have they failed in lowering coronary heart disease risk? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US National Institutes of Health, ClinicalTrials.gov. Further cardiovascular outcomes research with PCSK9 inhibition in subjects with elevated risk (FOURIER). November 1, 2013. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01764633. Accessed November 20, 2013.