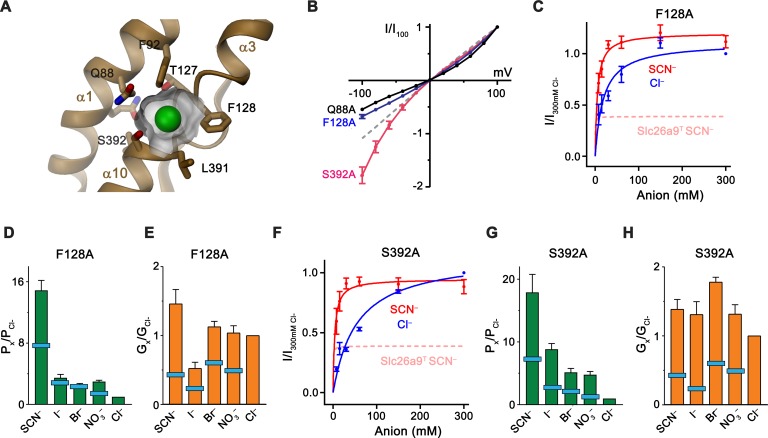

Figure 7. Substrate binding site.

(A) Structure of the Cl– binding site. The molecular surface of the binding pocket is shown. Selected residues are displayed as sticks. Bound Cl– is shown as a green sphere. (B) I-V relationships of selected Cl– binding site mutants (Q88A, n = 5; F128A, n = 8; S392A, n = 5). Data for WT Slc26a9T is shown as dashed line for comparison. (C) Conductance-concentration relationships of anion transport across the Slc26a9T mutant F128A (n = 3). For comparison, SCN– conductance–concentration relationship for non-mutated Slc26a9T is shown as a pink dotted line. (D) Permeability (Px/PCl) and (E) conductance ratios (Gx/GCl) of the Slc26a9T mutant F128A obtained from bi-ionic substitution experiments (Cl–, Br–, NO3–, SCN–, n = 8; I–, n = 3). The light-blue bars indicate corresponding values for WT Slc26a9T. (F) Conductance-concentration relationships of anion transport across the Slc26a9T mutant S392A (n = 5). For comparison, SCN– conductance–concentration relationship for non-mutated Slc26a9T is shown as a pink dotted line. (G) Permeability (Px/PCl) and (H) conductance ratios (Gx/GCl) of the Slc26a9T mutant S392A obtained from bi-ionic substitution experiments (Cl–, Br–, n = 5; NO3–, SCN–, I–, n = 4). The light-blue bars indicate corresponding values for WT Slc26a9T. Data was recorded from excised patches either in symmetric 150 mM Cl– (B), the indicated intracellular anion-concentrations with 7.5 mM extracellular Cl– (C and F), or at equimolar bi-ionic conditions containing 150 mM extracellular Cl– and 150 mM of the indicated intracellular anion (D, E, G, H). Data show mean values of the indicated number of biological replicates, errors are s.e.m.. C-H, Data were recorded at −100 mV.