Abstract

Background

The goal of this study was to evaluate the long-term results of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) using internal thoracic artery (ITA) grafts in hemodialysis (HD) patients with arteriovenous (AV) fistulae or AV grafts involving the ipsilateral or contralateral brachial artery or radial artery.

Methods

From March 2007 to May 2017, 76 end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients with an upper limb AV fistula or graft for HD underwent CABG at a single center. Group A included 23 patients who underwent CABG using an ITA graft ipsilateral to the AV vascular access (AVVA); Group B included 22 patients who underwent CABG using a contralateral ITA with AVVA; and Group C included 29 patients who underwent CABG with AVVA without the use of an ITA graft. The primary end-point was death from any cause.

Results

The average follow-up period was 34.4 ± 26.9 months. Death from any cause occurred in 6 (26.09%) patients in Group A, 8 (36.36%) patients in Group B, and 17 (58.62%) patients in Group C (log-rank p = 0.04). There was no significant difference in death rate between Groups A and B. The risk of death was lower in the patients with CABG using an ITA graft (ITA CABG) compared to the patients without ITA CABG [HR 0.41 (95% CI, 0.20-0.84), p = 0.015].

Conclusions

The HD patients who underwent CABG with an ipsilateral location of the ITA and AVVA did not have an increased risk of death compared to the patients who underwent CABG with a contralateral location of the ITA and AVVA. In addition, the use of ITA in CABG resulted in better outcomes in the HD patients.

Keywords: Chronic renal failure, Coronary artery bypass graft, Steal phenomenon, Uremia

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death in hemodialysis (HD) patients.1-3 Taiwan has the highest prevalence of HD in the world.4 Because HD patients now have access to health care under the National Health Insurance program, their survival time has been extended. The longer survival duration has meant that HD patients increasingly live long enough to develop age-related diseases such as multiple vessel disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), and cardiovascular disease. As such, HD patients may need to undergo cardiovascular revascularization. According to previous studies on HD patients, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has a better outcome than percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs).5-8 Unlike saphenous vein grafts (SVGs), internal thoracic arteries (ITAs) can remain patent for many years postoperatively (10-year patency > 90%).9 The use of ITAs improves survival and greatly reduces the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACES) in CABG patients.10,11

However, coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is a condition in CABG patients who have ipsilateral ITAs with arteriovenous vascular access (AVVA).12 Steal syndrome is considered to be a risk factor for the development of postoperative myocardial ischemia during HD.13,14 A high flow AVVA with low resistance bed may draw flow away from the relatively high resistance zone where the ITA graft is anastomosed to the coronary artery. The reversal of flow in the ITA may then cause myocardial ischemia.12,14 In previous retrospective studies, ipsilateral AVVA has been found to increase the risk of late death or MACEs.12,15 In this study, we used total arterial revascularization (TAR) in over 30% of CABG procedures in HD patients. We used the TAR technique to harvest pedicled ITA grafts from the chest wall, and the distal end of the ITA was anastomosed to the side of a free radial arterial graft to create a composite arterial graft. Using a sequential grafting technique, the radial artery graft portion was anastomosed to all of the target coronary arteries to complete TAR CABG (Figure 1). Thus, ITAs were the sole blood source of all of grafts. The effect of TAR on steal phenomenon has not been clearly established, and therefore the purpose of this study was to determine whether ipsilateral AVVA increased the risk of late death after isolated CABG in HD patients.

Figure 1.

Black arrow head is left internal thoracic artery. White arrow head is radial artery graft. White arrow is that left internal thoracic artery was end-to-side anastmosed with radial artery graft as T-graft.

METHODS

All data used in this retrospective cohort study were obtained from patient medical records at our hospital (paper and electronic files). All patients were being treated with HD due to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and underwent CABG at a single center between March 2007 and May 2017. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

The inclusion criteria were an age between 20 and 85 years, availability of clinical data, and presence of a patent upper extremity AVVA (native fistula or synthetic graft) for dialysis access. Patients using a catheter for vascular access to dialysis were excluded from this study.

The eligible patients were divided into three groups: Group A included patients who received CABG with an ipsilateral location of the ITA and AVVA; Group B included those who underwent CABG with a contralateral location of the ITA and AVVA; and Group C included those with HD AVVA, but who received CABG using a great SVG with or without radial artery graft. The clinical data of each patient included the following: a medical history of underlying diseases, surgical reports, laboratory analyses, and fatal events. The primary end-point was death from any cause.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS version 22.0; International Business Machines Corp., New York, USA). Continuous variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical data were reported as number and percentage. Data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, Mann-Whitney U-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test.

We examined potential preoperative and intraoperative risk factors for mortality using univariate and multivariate analyses. The factors were selected on the basis of clinical relevance or when significance of univariate association exhibited a p value less than 0.05. Event-free survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Independent predictors of long-term survival were determined using a Cox proportional hazards model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

We identified 86 HD patients who underwent isolated CABG at our center during the study period, of whom 12 were excluded. HD access failure occurred in 5 patients, and 7 patients were dialyzed via a venous catheter. A total of 74 patients were included in the study, including 23 in Group A, 22 in Group B, and 29 in Group C (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

86 patients have been underwent isolated CABG and hemodialysis. After 12 patients were excluded, only 74 patients were included. According to their graft type and location, they were divided into three groups.

The baseline demographic and clinical data of the patients are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the study groups in baseline characteristics. The operation data are presented in Table 2. In patients with on-pump CABG, the median clamping time in Group A was 99.5 minutes, compared to 114 minutes in Group B and 127.5 minutes in Group C. There was no significant difference in clamping time. The TAR rate was highest in Group B. With respect to pump type, Group B included only 3 patients (13.6%) with on-pump CABG.

Table 1. Patients’ baseline characteristics.

| A (n = 23) | B (n = 22) | C (n = 29) | p value | |

| Age | 59 (54-66) | 58.5 (51-62.5) | 61 (58.5-70.5) | 0.086 |

| Sex | 0.137 | |||

| Female | 9 (39.1%) | 4 (18.2%) | 5 (17.2%) | |

| Male | 14 (60.9%) | 18 (81.8%) | 24 (82.8%) | |

| CAD | 0.193 | |||

| 1 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | |

| 2 | 1 (4.3%) | 3 (13.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 3 | 22 (95.7%) | 19 (86.4%) | 28 (96.6%) | |

| LM lesion | 7 (30.4%) | 6 (27.3%) | 8 (27.6%) | 0.966 |

| LVEF | 50 (39-53) | 44 (36.5-59.3) | 41 (35-52.5) | 0.492 |

| EuroSCORE | 7 (5-10) | 8 (5-10) | 8 (6-12) | 0.247 |

| Unstable angina | 8 (34.8%) | 8 (36.4%) | 6 (20.7%) | 0.391 |

| Recent MI | 9 (39.1%) | 8 (36.4%) | 6 (20.7%) | 0.295 |

| Previous MI | 5 (21.7%) | 4 (18.2%) | 5 (17.2%) | 0.914 |

| AMI | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (13.8%) | 0.130 |

| pre OP IABP | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.9%) | 0.393 |

| LVEF | 0.919 | |||

| > 30 | 19 (82.6%) | 19 (86.4%) | 25 (86.2%) | |

| ≤ 30 | 4 (17.4%) | 3 (13.6%) | 4 (13.8%) | |

| DM | 16 (69.6%) | 14 (63.6%) | 13 (44.8%) | 0.164 |

| Hypertension | 13 (56.5%) | 14 (63.6%) | 11 (37.9%) | 0.160 |

| Stroke | 6 (26.1%) | 5 (22.7%) | 4 (13.8%) | 0.518 |

Chi-Square test. Kruskal-Wallis test.

Continuous data are expressed as median (IQR).

Categorical data are expressed as number and percentage.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LM, left main; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; OP, operation.

Table 2. Operation data.

| A (n = 23) | B (n = 22) | C (n = 29) | p value | |

| ITA | < 0.001 | |||

| LITA | 20 (87.0%) | 13 (59.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| RITA | 3 (13.0%) | 9 (40.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 29 (100.0%) | |

| TAR | 8 (34.8%) | 18 (81.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | < 0.001 |

| CABG | 0.784 | |||

| 1 | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (3.4%) | |

| 2 | 2 (8.7%) | 3 (13.6%) | 4 (13.8%) | |

| 3 | 10 (43.5%) | 11 (50.0%) | 14 (48.3%) | |

| 4 | 9 (39.1%) | 6 (27.3%) | 7 (24.1%) | |

| 5 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.5%) | 3 (10.3%) | |

| Pump type | < 0.001 | |||

| Robotic | 5 (21.7%) | 16 (72.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| OPCABG | 8 (34.8%) | 3 (13.6%) | 16 (55.2%) | |

| On pump | 10 (43.5%) | 3 (13.6%) | 13 (44.8%) | |

| OPCABG | 13 (56.5%) | 18 (81.8%) | 16 (55.2%) | 0.103 |

| In OP IABP | 7 (30.4%) | 11 (50.0%) | 7 (24.1%) | 0.142 |

| Pump time (n = 9 vs. 3 vs. 12) | 141 (130.5-157.5) | 147 | 145 (112-188.5) | 0.604 |

| Clamp time (n = 10 vs. 3 vs. 8) | 99.5 (85.3-111.5) | 114 | 127.5 (103.8-157.8) | 0.048* |

Chi-Square test. Kruskal-Wallis test.

Continuous data are expressed as median (IQR).

Categorical data are expressed as number and percentage.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LITA, left internal thoracic artery; OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass graft; RITA, right internal thoracic artery; Robotic, Robotic-assisted CABG; TAR, total arterial revascularization.

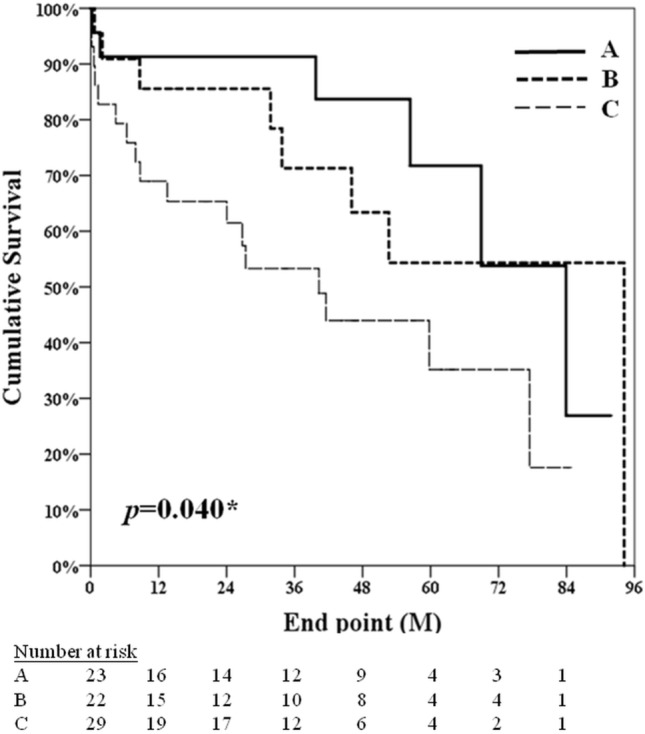

The 30-day mortality rate was 6.75% (5 of 74 patients). The follow-up period ranged from 0.17 to 94.17 months (average 34.4 ± 26.9 months) for all patients. Death from any cause occurred in 6 (26.09%) patients in Group A, 8 (36.36%) patients in Group B, and 17 (58.62%) patients in Group C. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the three groups (log-rank p = 0.04) are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the three groups (log-rank p = 0.04). Group A comprised patients underwent CABG using internal thoracic artery graft (ITA) ipsilateral to the AV shunt; group B comprised patients underwent CABG using a contralateral ITA with AV shunt; group C comprised patients underwent CABG with AV shunt without use of ITA.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for death from any cause was performed based on the patients’ characteristics, including age, left main (LM) lesions, Euroscore, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 30%, DM, use of the ITA in CABG, TAR, and pump type. The model showed that the risk of death was lower in the patients who received CABG with use of the ITA compared with the patients who received CABG without use of the ITA [HR 0.41 (95% CI, 0.20-0.84), p = 0.015]. There was no significant difference in the risk of mortality between Group A and Group B. The risk of death was lower in the patients who underwent CABG with TAR [HR 0.30 (95% CI, 0.12-0.74), p = 0.009] (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate Cox-proportional hazard models for associations of patient factors with all-cause death.

| Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value | |

| Age | 1.10 | (1.05-1.16) | < 0.001 |

| LM lesion | 0.53 | (0.22-1.31) | 0.170 |

| EuroSCORE | 1.05 | (0.95-1.17) | 0.316 |

| LVEF ≤ 30 | 0.70 | (0.24-2.01) | 0.506 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.98 | (0.47-2.02) | 0.955 |

| Group | |||

| A | 0.35 | (0.14-0.90) | 0.030* |

| B | 0.46 | (0.19-1.12) | 0.089 |

| C | ref. | ||

| With ITA | 0.41 | (0.20-0.84) | 0.015* |

| TAR | 0.30 | (0.12-0.74) | 0.009# |

| Pump type | |||

| Robotic | ref. | ||

| OPCABG | 3.37 | (1.18-9.64) | 0.023* |

| On pump | 3.05 | (1.04-8.94) | 0.042* |

Cox regression. * p < 0.05, # p < 0.01.

ITA, internal thoracic artery; LM, left main; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass garft; Robotic, robotic-assisted off-pump coronary artery bypass graft; TAR, total arterial revascularization.

The Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients who received CABG with use of the ITA (group A+B) was 68.89%, compared to 41.38% in those who received CABG without ITA (group C) (log-rank p = 0.012) (Figure 4). Cox proportional hazards analysis revealed that the patients aged between 25-65 years [HR 0.37, (95% CI 0.14-0.96), p = 0.042] had a significantly longer overall survival (Table 4).

Figure 4.

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the two groups (log-rank p = 0.012). Group A+B comprised patients who received CABG with the use of internal thoracic artery (ITA); Group C comprised those who received CABG without ITA.

Table 4. Outcome: death.

| Age | |||||||||

| Total (n = 74) | 25-65 (n = 53) | 66-84 (n = 21) | |||||||

| HR | (95% CI) | p value | HR | (95% CI) | p value | HR | (95% CI) | p value | |

| OP type | |||||||||

| No ITA | ref. | ref. | ref. | ||||||

| ITA | 0.41 | (0.20-0.84) | 0.015* | 0.37 | (0.14-0.96) | 0.042* | 0.75 | (0.23-2.40) | 0.625 |

Cox regression. * p < 0.05, # p < 0.01.

ITA, internal thoracic artery; OP, operation.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report our single-center experience of patients with ESRD and upper arm AVVA undergoing CABG. We were not able to establish either the presence or absence of the steal phenomenon of ITA grafts during HD. However, if the steal phenomenon was indeed present, it did not seem to affect the long-term outcomes of the patients. There was no significant difference in survival rate between the patients receiving CABG with ipsilateral AVVA of the ITA and those receiving CABG with a contralateral AVVA of the ITA based on long-term follow-up data. The patients who received CABG with the ITA had better long-term results than those who received CABG without use of the ITA. In this study, TAR appeared to decrease the risk of death. Furthermore, in the younger patients (< 65 years), outcomes were better in the patients who received CABG with use of the ITA.

A previous retrospective cohort study conducted on a small population of HD patients from a single center showed that CABG with an ipsilateral ITA and AVVA [adjusted HR 3.047, (95% CI 0.996-1.000), p = 0.081] did not increase the risk of death compared with CABG with a contralateral ITA and AVVA [adjusted HR 0.173, (95% CI 0.997-1.002), p = 0.678].16 Moreover, two retrospective investigations of dialysis patients revealed that revascularization of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery using an ipsilateral ITA and AVVA in CABG did not increase operative mortality or the risk of death and cardiac events.17,18 In the current study, 34.8% of the patients in Group A and 81.8% in Group B received CABG with TAR. We hypothesize that blood flow in the ITA in TAR with a sequential grafting technique is greater than that in ITA revascularization to the LAD artery only, and that greater blood flow in the ITA may tend to prevent or reduce the steal phenomenon. This may explain why there was no significant difference in long-term survival in the patients receiving CABG with either ipsilateral ITA CABG or contralateral ITA CABG.

A previous cohort study of 14,316 HD patients showed that use of the ITA was associated with a 12-15% lower risk of death, and a 9-14% lower risk of the composite outcome of death or myocardial infarction compared with use of SVG in patients with ESRD undergoing CABG.19 Another retrospective study of a general population included 749 patients who received CABG with the ITA and 4888 patients who received CABG with SVG only. The results showed that use of the ITA was an independent factor for improved survival, and that it was associated with a relative risk of death of 0.73 (95% CI 0.64-0.83).20,21 Moreover, using radial arteries as a second arterial conduit in CABG-ITA-LAD as opposed to vein grafting improved the long-term outcomes.22,23 In our study, TAR grafts included ITAs as an inflow conduit and radial arteries as a T-graft conduit. The long-term outcomes were better when using radial arteries as a second conduit in our HD patients.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a small retrospective cohort study conducted at a single center. Second, this study did not collect data on the actual blood flow in the ITA of our patients. Third, arteriovenous fistula and arteriovenous graft data were incomplete. Fourth, the causes of death could not be clearly defined by telephone surveys.

CONCLUSIONS

CABG with an ipsilateral location of the ITA and AVVA did not increase the risk of death from any cause compared with CABG with a contralateral location of the ITA and AVVA in the HD patients. We did not prove the presence or absence of the steal phenomenon of ITA grafts during HD. Nonetheless, if the steal phenomenon was indeed present, it did not appear to affect the long-term outcomes. However, we did not have complete arteriovenous fistula and arteriovenous graft data, and this may have biased the results. Finally, the use of ITA and TAR decreased the risk of death in the HD patients in this study.

Acknowledgments

Author contribution: Conception and design: Yung-Szu Wu, Hao-Ji Wei. Analysis and interpretation: Yung-Szu Wu, Chiann-Yi Hsu. Data collection: Yung-Szu Wu, Hao-Ji Wei. Writing the article: Yung-Szu Wu, Shih-Rong Hsieh, Chung-Lin Tsai. Critical revision of the article: Yung-Szu Wu, Shih-Rong Hsieh.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wen CP, Cheng TYD, Tsai MK, et al. All-cause mortality attributable to chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study based on 462 293 adults in Taiwan. Lancet. 2008;28;371:2173–2182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashrith G, Elayda MA, Wilson JM. Revascularization options in patients with chronic kidney disease. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masakane I, Nakai S, Ogata S, et al. An overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan (As of 31 December 2013). Ther Apher Dial. 2015;19:540–574. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu PC, Wu V. Chronic kidney disease in Taiwan’s aging population. Acta Nephrol. 2014;28:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunagawa G, Komiya T, Tamura N, et al. Coronary artery bypass surgery is superior to percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents for patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1896–1900; discussion 1900. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marui A, Kimura T, Nishiwaki N, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis (5-year outcomes of the CREDO-Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort-2). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou C, Hsieh T, Wang C, et al. Long-term outcomes of dialysis patients after coronary revascularization: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Arch Med Res. 2014;45:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li HR, Hsu CP, Sung SH, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with diabetic nephropathy and left main coronary artery disease. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2017;33:119–126. doi: 10.6515/ACS20160623A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:2610–2642. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823b5fee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinoshita T, Asai T, Murakami Y, et al. Bilateral versus single internal thoracic artery grafting in dialysis patients with multivessel disease. Heart Surg Forum. 2010;13:E280–E286. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20091182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita T, Asai T, Murakami Y, et al. Efficacy of bilateral internal thoracic artery grafting in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aala A, Sharif S, Parikh L, et al. High-output cardiac failure and coronary steal with an arteriovenous fistula. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71:896–903. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cua B, Mamdani N, Halpin D, et al. Review of coronary subclavian steal syndrome. J Cardiol. 2017;70:432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowley SD, Butterly DW, Peter RH, et al. Coronary steal from a left internal mammary artery coronary bypass graft by a left upper extremity arteriovenous hemodialysis fistula. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:852–855. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.35701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman L, Tkacheva I, Efrati S, et al. Effect of arteriovenous hemodialysis shunt location on cardiac events in patients having coronary artery bypass graft using an internal thoracic artery. Ther Apher Dial. 2014;18:450–454. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman L, Beberashvili I, Abu Tair A, et al. Effect of hemodialysis access blood flow on cardiac events after coronary artery bypass grafting using an internal thoracic artery. J Vasc Access. 2017;18:301–306. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takami Y, Tajima K, Kato W, et al. Effects of the side of arteriovenous fistula on outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery in hemodialysis-dependent patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han Y, Choo SJ, Kwon H, et al. Effects of upper-extremity vascular access creation on cardiac events in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0184168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shilane D, Hlatky MA, Winkelmayer WC, et al. Coronary artery bypass graft type and outcomes in maintenance dialysis. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2015;56:463–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motwani JG, Topol EJ. Aortocoronary saphenous vein graft disease: pathogenesis, predisposition, and prevention. Circulation. 1998;97:916–931. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.9.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron A, Davis KB, Green G, et al. Coronary bypass surgery with internal-thoracic-artery grafts--effects on survival over a 15-year period. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:216–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tranbaugh RF, Dimitrova KR, Friedmann P, et al. Radial artery conduits improve long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zacharias A, Habib RH, Schwann TA, et al. Improved survival with radial artery versus vein conduits in coronary bypass surgery with left internal thoracic artery to left anterior descending artery grafting. Circulation. 2004;109:1489–1496. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121743.10146.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]