Abstract

Chronic inflammation plays a significant role in lifestyle-related diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and obesity/impaired glucose tolerance. Curcumin is a natural extract that possesses numerous physiological properties, as indicated by its anti-inflammatory action. The mechanisms underlying these effects include the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and Toll-like receptor 4-dependent signalling pathways and the activation of a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma pathway. However, the bioavailability of curcumin is very low in humans. To resolve this issue, several drug delivery systems have been developed and a number of clinical trials have reported beneficial effects of curcumin in the management of inflammation-related diseases. It is expected that evidence regarding the clinical application of curcumin in lifestyle-related diseases associated with chronic inflammation will accumulate over time.

Keywords: Inflammation, curcumin, lifestyle-related diseases, cardiovascular risk factor, natural product

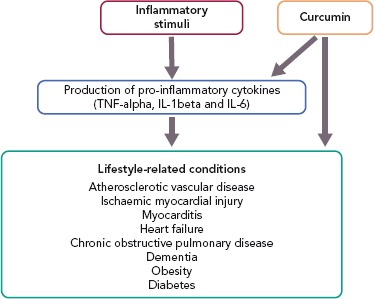

Inflammation involves an array of processes in response to tissue damage resulting from oxidative stress or other causes and triggers repair, such as subsequent extracellular matrix remodelling and fibrosis.[1–3] Chronic inflammation continues for a prolonged period, lasting from several months to several years, and is characterised by tissue invasion by inflammatory macrophages. This induces the expression of inflammatory cytokines or growth factors, which is associated with the pathophysiology of various lifestyle-related diseases including cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other related diseases, such as dementia.[4–6] Atherosclerosis is a chronic illness associated with inflammation and is a major cause of cardiovascular disease.[7–10]

Curcumin is a polyphenol found in the spice turmeric that is used as a natural drug.[11–13] Curcumin exhibits various physiological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anticancer activities.[4,12–14] It inhibits signalling pathways, such as nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kappaB) and myeloid differentiation protein 2-Toll-like receptor 4 co-receptor pathways, activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) and inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin (IL)-1beta (Figure 1).[4,15]

Figure 1: Actions of Curcumin on Lifestyle-related Conditions.

IL-1beta = interleukin-1beta; IL-6 = interleukin-6; TNF-alpha = tumour necrosis factor-alpha.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved curcumin as a compound that is “generally recognised as safe” and a clinical trial reported that it was well tolerated and safe at doses as high as 4,000–8,000 mg/kg per day.[11] Trials in humans have reported beneficial effects of curcumin and it appears to have a role in treating lifestyle-related diseases associated with inflammation.

Curcumin and Atherosclerosis

Risk factors for atherosclerosis, including hypertension, diabetes and smoking, cause a chronic inflammatory response. Oxidative stress can cause atherosclerotic plaques to become unstable and rupture, possibly triggering thrombosis. Statins are drugs with anti-inflammatory effects that are used for treating high cholesterol and various studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.[16]

Risk factors associated with atherosclerosis lead to the production of inflammatory cytokines IL-1beta and TNF-alpha in the arterial walls via an increase in lipid peroxides and free radicals. These inflammatory cytokines produce IL-6 and are related to the adhesion and accumulation of inflammatory cells in the vessel walls.[16] Macrophages are the most abundant immune cells in atherosclerotic lesions and they play an important role in every stage of the disease, from lesion formation to plaque rupture. Macrophages are involved in the production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and proteases as well as having a role in foam cell formation.[17] Numerous prospective cohort studies have reported that various inflammatory markers in the blood, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), are associated with the onset of cardiovascular disease.[18]

Zhang et al. evaluated a model of atherosclerosis in which ApoE knockout (ApoE-/-) mice were fed a high-fat diet. They found that curcumin inhibited the expression of Toll-like receptor 4 in atherosclerotic plaques, macrophage invasion and NF-kappaB activation in the aorta; reduced the level of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in the aorta and blood; and reduced the size of atherosclerotic regions, inhibiting their expansion.[19] Ghosh et al. initiated renal failure in LDL receptor knockout mice via partial nephrectomy. They induced atherosclerosis with a high-fat diet and reported that curcumin reduced the area of atherosclerotic lesions by 63%.[20]

Curcumin and Ischaemic Myocardial Damage

The death of myocytes due to MI temporarily causes an intense inflammatory response via the activation of Toll-like receptors.[21] In a rodent model of MI, considerably increased expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-alpha, IL-1beta and IL-6, was evident after a few hours in some cases (several hours to 1 day).[22] In addition, the generation of reactive oxygen species due to ischaemia is essential in activating inflammatory responses.[21]

Several studies suggest that curcumin has an inhibitory effect on NF-kappaB, which is a pivotal mediator of inflammatory responses. Lv et al. assessed a rat model of MI in which they ligated the left anterior descending artery. They found that administering 150 mg/kg curcumin on the day after ligation significantly inhibited an increase in NF-kappaB expression as a result of MI and increased the PPAR-gamma expression, which is involved in anti-inflammatory signalling, consequently reducing the infarct size.[23] In a rabbit model of myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury during cardiopulmonary bypass, Saeidinia et al. reported that curcumin inhibited NF-kappaB activation in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes, thus reducing TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-8 levels in the blood, and that it inhibited monocyte apoptosis.[24]

Early growth response 1 plays a key role in the pathophysiology of acute and chronic cardiovascular disease and is associated with induction of TNF-alpha and IL-6 expression. Wang et al. studied a rat model of myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury and found that previous administration of curcumin inhibited early growth response 1 expression and reduced the infarct size.[25]

Curcumin and Myocarditis and Heart Failure

Myocarditis is often induced by a viral infection but has non-infectious causes, including autoimmune disorders.[26,27] Heart failure is the final stage of cardiovascular disease. Chronic inflammation and subsequent myocyte death are associated with heart failure. Patients with heart failure have an abnormal immune response that disrupts wound healing and prolongs inflammation, consequently worsening heart failure.[28] A high level of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha has been reported in the blood of patients with chronic heart failure.[29]

The impact of curcumin in myocarditis has been studied using a number of rodent models. In coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis, curcumin inhibited the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase–Akt–NF-kappaB signalling pathway and inhibited the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-1beta, both systemically and in the myocardium; thus, reducing the inflammatory response.[30] Hernández et al. evaluated a mouse model of myocarditis caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and reported that curcumin inhibited the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 in the myocardium as well as inhibiting inflammation in the myocardium and increased the survival rate of mice.[31] TNF-alpha and IL-6 are inflammatory cytokines, whereas IL-4 and IL-13 are anti-inflammatory cytokines. Curcumin inhibited the expression of TNF-alpha and IL-6 and increased the expression of IL-4 and IL-13 in autoimmune acute myocarditis induced by cardiac myosin.[32] Moreover, curcumin enhanced signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 phosphorylation and induced M2 macrophage polarisation, thus inhibiting myocarditis progression.[32]

Morimoto et al. studied two rat models of heart failure caused by hypertension and MI and showed that curcumin inhibits p300 histone acetyltransferase activity, thus inhibiting the development of left ventricular hypertrophy and left ventricular systolic dysfunction.[33] In a rat model of doxorubicin-induced heart failure, curcumin inhibited the expression of atrial natriuretic factor, brain natriuretic peptide and beta-myosin heavy chain.[34] The inhibition of heart failure by curcumin may thus be associated with its anti-inflammatory action.

Curcumin and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

COPD is a family of diseases mainly characterised by airflow obstruction due to airway inflammation and remodelling. Several clinical studies have demonstrated the relationship between COPD and an increase in inflammatory markers, such as TNF-alpha, IL-6 and CRP.[35,36] Smoking is the primary cause of COPD, and can cause systemic inflammation, but this is further exacerbated in people with COPD.[35,36] COPD causes various complications, including MI, stroke and lung cancer. The most common comorbidity in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD is cardiovascular disease. One study suggested that chronic inflammation due to COPD exacerbates atherosclerosis, both directly and indirectly, and promotes thrombosis by weakening plaque.[37]

Several studies have demonstrated the possible benefits of curcumin in COPD. Moghaddam et al. used a mouse model of K-ras-induced lung cancer in which Haemophilus influenzae induced COPD-like airway inflammation and showed that curcumin inhibited neutrophil migration to the lungs.[38] Yuan et al. studied a mouse model of COPD induced by lipopolysaccharide and cigarette smoke, reporting that curcumin inhibited the degradation of IkappaB-alpha protein and the expression of cyclooxygenase-2, thus reducing airway inflammation and remodelling.[39] Funamoto et al. conducted a clinical trial including patients with mild COPD in which the oxidised LDL – alpha-1-antitrypsin LDL – was significantly decreased in those taking highly absorbable curcumin compared with those taking a placebo.[40]

Curcumin, Obesity and Diabetes

Adipose tissue is a multifunctional endocrine organ that releases various inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and physiologically active peptides.[41,42] Obesity is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.[41,43] The accumulation of pericardial fat and myocardial steatosis is associated with the progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis. In obese patients, the secretion of inflammatory adipocytokines, such as TNF-alpha and IL-6, is increased and the secretion of anti-inflammatory adipocytokines is inhibited in enlarged mast cells in the visceral adipose tissue.[42,43]

Several rodent studies have assessed the effects of curcumin in models of obesity. In a mouse model of obesity due to a high-fat diet and in a model of genetic obesity, curcumin reduced macrophage invasion of adipose tissue, increased adiponectin production (which has anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic actions) and inhibited adipose tissue inflammation.[44]

Pan et al. evaluated a mouse model of obesity due to a high-fat diet and reported that ingestion of curcumin inhibited weight gain, reduced fat accretion due to a high-fat diet and significantly improved the serum lipid profile (including serum levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and free fatty acids).[45] In addition, curcumin increased the adipose triglyceride lipase and hormone-sensitive lipase protein expression by activating PPAR-gamma/alpha and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha in adipose tissue. Further, curcumin broke down lipids and improved glycolipid metabolism.[45] Curcumin administration via percutaneous absorption in obese rats improved serum leptin levels and reduced adipose tissue volume to a level comparable with that in normal rats.[46]

Jazayeri-Tehrani et al. conducted a clinical trial involving 84 overweight or obese patients who were diagnosed with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.[47] They noted a decrease in TNF-alpha, high-sensitivity CRP, IL-6 and LDL-cholesterol as well as an increase in HDL-cholesterol in the blood. There was also increased absorption efficiency in patients taking nanocurcumin compared to those taking placebo. Nesfatin, an appetite-regulating protein, is significantly increased in patients taking nanocurcumin. When patients taking placebo were compared with those taking nanocurcumin, the two groups had a similar percentage decrease in BMI, but those taking nanocurcumin had a significantly greater percentage decrease in abdominal circumference.[47]

In people with type 2 diabetes, trials have shown that curcumin decreased leptin and increased adiponectin in the blood and resulted in improved lipid metabolism.[48,49]

Curcumin and Dementia

Over the past few years, the role of inflammation has been recognised in the onset and progression of dementia.[50,51] One study reported that dementia onset may be related to conditions such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes, independent of cardiovascular risk factors.[52]

The onset of Alzheimer’s-type dementia is closely correlated with inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain.[50,53] NF-kappaB activation in the glial cells of Alzheimer’s patients induces increased expression of inflammatory cytokines and contributes to neuronal degeneration in the brain.[53] Levels of CRP, IL-6 and alpha1-antichymotrypsin in the blood are significantly correlated with the degree of dementia.[50]

Research into the possible impact of curcumin on dementia is currently very limited. However, Liu et al. found that curcumin significantly reduced spatial memory deficit and promoted the function of cholinergic neurons in mice; this improvement was associated with the inhibition of NF-kappaB signalling pathways and enhanced transcription by PPAR-gamma.[54] Small et al. reported that highly absorbable curcumin reduced amyloid and tau accumulation in the brains of adults with no cognitive impairment and may consequently improve memory and attention.[55]

Trials on Anti-inflammatory Effects of Curcumin

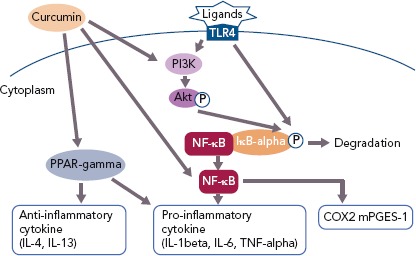

The anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin forms the basis for its potential clinical applications (Figure 2). A large body of clinical evidence is expected to accumulate in the future. Among trials registered at Clinicaltrials.gov, 162 studies are related to the anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin. Of these, 50 are currently on-going, 70 are complete and 42 have been withdrawn, have unknown status or have been terminated. Of the 50 completed studies, the 10 randomised double-blind and placebo-controlled comparative studies are listed in Table 1. The results of eight of these studies were significant. As the absorption of curcumin is very poor, most studies that reported significant effects used a large dose of curcumin (>1.5 g/day) or employed strategies to increase its absorption, such as using a drug delivery system.

Figure 2: The Mechanisms of Curcumin Action on Inflammation.

COX2 = cyclooxygenase-2; IĸB = inhibitor of kappaB; IL = interleukin; mPGES-1 = microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1; NF-ĸB = nuclear factor-kappaB; PI3K = phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; PPAR-gamma = peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma; TLR4 = toll-like receptor 4; TNF-alpha = tumour necrosis factor-alpha.

Table 1: Completed Randomised Trials into Curcurmin.

| Study | Purpose | Subjects and Treatment | Endpoint | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adibian et al. 2019[56] | To investigate the effects of curcumin supplementation on systemic inflammation, serum levels of adiponectin and lipid profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes |

|

hs-CRP | Compared with control, curcumin decreased hs-CRP significantly (p<0.05) |

| Jazayeri-Tehrani et al. 2019[47] | To determine the effects of nanocurcumin on overweight/obese non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients by assessing glucose, lipids, inflammation, insulin resistance and liver function indices, especially through nesfatin |

|

TNF-alpha, hs-CRP, IL-6 | Compared with placebo, nanocurcumin significantly decreased levels of TNF-alpha, hs-CRP and IL-6 (p<0.05) |

| Krishnareddy et al. 2019[57] | To investigate the efficacy of a novel food-grade free-curcuminoid delivery system in improving markers of hepatic function (inflammation and oxidative stress) in chronic alcoholics |

|

IL-6, C-reactive protein, glutathione, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase | Compared to both baseline and the placebo group, curcumin-galactomannoside complex significantly increased levels of glutathione, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase (p<0.001) and decreased IL-6 and C-reactive protein (p<0.001) |

| Mohammadi et al, 2018[58] | To investigate the effects of unformulated curcumin and phospholipidated curcumin on anti-Hsp27 in patients with metabolic syndrome |

|

Anti-Hsp27 | Curcumin and phospholipidated curcumin did not modify anti-Hsp27 concentration |

| Vors et al. 2018[59] | To investigate: the bioavailability of resveratrol consumed in combination with curcumin after consumption of a high-fat meal; and the acute combined effects of this combination on the postprandial inflammatory response of subjects with abdominal obesity |

|

IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, C-reactive protein, sVCAM-1, sICAM-1, soluble E-selectin | Resveratorol/curcumin significantly decreased the cumulative postprandial response of sVCAM-1 compared to placebo (p=0.01) |

| Panahi et al. 2018[60] | To evaluate the impact of curcuminoids plus piperine administration on glycaemic, hepatic and inflammatory biomarkers in people with type 2 diabetes |

|

hs-CRP | No significant differences in hs-CRP concentrations were observed between curcuminoids and placebo groups |

| Funamoto et al. 2016[40] | To evaluate the efficacy of curcumin using dispersion technology in patients with mild COPD by examining its effects on oxidative stress markers and inflammatory markers |

|

C-reactive protein, TNF-alpha, IL-6, SAA-LDL, alpha-1-antitrypsin-LDL | Percentage change in alpha1-antitrypsin-LDL level was significantly lower in the curcumin group compared with placebo (p=0.02) |

| Panahi et al. 2016[61] | To investigate the efficacy of curcuminoids in reducing systemic oxidative burden in people with knee osteoarthritis |

|

Superoxide dismutase, glutathione, malondialdehyde | Curcuminoids induced significant elevation in serum superoxide dismutase activities (p<0.001), a borderline significant elevation in glutathione concentrations (p=0.064) and a significant reduction in malondialdehyde concentrations (p=0.044) compared with placebo |

| Panahi et al. 2015[62] | To study the effectiveness of supplementation with a bioavailable curcuminoid preparation on measures of oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with metabolic syndrome |

|

Superoxide dismutase, malondialdehyde, hs-CRP | Curcuminoid-piperine significantly improved serum superoxide dismutase activities (p<0.001) and reduced malondialdehyde (p<0.001) and C-reactive protein (p<0.001) concentrations compared with placebo |

| Usharani et al. 2018[63] | To compare the effects of NCB-02 (a standardised preparation of curcuminoids), atorvastatin and placebo on endothelial function and its biomarkers in people with type 2 diabetes |

|

Malondialdehyde, IL-6, TNF-alpha | Patients receiving curcumin showed significant reductions in the levels of malondialdehyde, IL-6 and TNF-alpha |

Anti-Hsp27 = antibody titers to heat shock protein 27; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; hs-CRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL = interleukin; MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; SAA-LDL = serum amyloid A-LDL complex; sICAM-1 = soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; sVCAM-1 = soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; TNF- alpha = tumour necrosis factor-alpha.

Drug Delivery Systems

Curcumin has beneficial effects on the status of various diseases involving chronic inflammation. However, the absorption of curcumin is poor, and even if absorbed into the body it is rapidly metabolised and excreted in faeces.[14] To overcome its low bioavailability, various drug delivery systems have been developed (Table 2). These include polymer nanoparticles, chitosan nanoparticles, colloidal nanoparticles, nanoemulsion and ligand-targeted liposomes.

Table 2: Results of Studies of Curcumin using Drug Delivery Systems to Increase Bioavailability.

| Study | Formulation | Advantage | Application | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| El-Naggar et al. 2010[64] | Biodegradable curcumin encapsulated in polylactide-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymer nanoparticles |

|

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats | Enhanced the suppressive effect on markers of hepatitis and oxidative stress |

| Karri et al. 2016[65] | Curcumin in chitosan nanoparticles impregnated into a collagen-alginate scaffold |

|

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats | Promoted wound healing |

| Hu et al. 2018[66] | Inhalable curcumin-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid large porous microparticles |

|

Rat pulmonary fibrosis models | Enhanced antifibrotic activity |

| Qiao et al. 2017[67] | Amphiphilic curcumin polymer |

|

Dextran sulphate sodium-induced mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease | Suppressed the progress of inflammation in the colon |

| Young et al. 2014[68] | Nano-emulsion curcumin |

|

Lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation model mice | Suppressed lipopolysaccharide-induced blood monocyte accumulation |

| Li et al. 2019[69] | E-selectin-modified atorvastatin calcium-and curcumin-loaded liposome |

|

ApoE-/- mice | Suppressed atherosclerosis |

| Funamoto et al. 2016[40] | Curcumin dispersed with colloidal nanoparticles |

|

People with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Suppressed an increase in alpha1-antitrypsin LDL |

The beneficial effects of these drug delivery systems on curcumin bioavailability have been reported in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, a pulmonary fibrosis rat model, a dextran sulphate sodium-induced inflammatory bowel disease mouse model and a lipopolysaccharide-stimulated acute inflammation mouse model.[64–68] E-selectin-modified liposome was effective for ApoE-/- mice.[69]

Moreover, Funamoto et al. reported that curcumin dispersed with colloidal nanoparticles (Theracurmin®) suppressed an increase in alpha1-antitrypsin LDL levels in people with mild COPD.[40] The improvement in the bioavailability of curcumin through the development of drug delivery systems may contribute to the successful clinical application of curcumin.

Conclusion

A number of studies have reported the efficacy of curcurmin and the mechanisms by which its anti-inflammatory activity could treat various lifestyle-related conditions associated with chronic inflammation, including atherosclerosis, heart failure, obesity, diabetes and other related diseases, such as dementia. Most of these studies have involved animal experiments; however, there are several reports on the benefits of curcumin use in humans. Because curcumin has extremely low bioavailability in humans, an appropriate drug delivery system is necessary for its clinical application.

It is important to study the relationship between the structure and activity of curcumin and to develop novel compounds that are more effective than natural curcumin. Additional clinical trials involving drug delivery systems for curcumin in humans need to be conducted to determine the benefits of curcumin treatment in conditions associated with inflammation.

References

- 1.Libby P. Inflammatory mechanisms: the molecular basis of inflammation and disease. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S140–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheresh P, Kim SJ, Tulasiram S et al. Oxidative stress and pulmonary fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1028–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix in myocardial injury, repair, and remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1600–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI87491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu XY, Meng X, Li S et al. Bioactivity, health benefits, and related molecular mechanisms of curcumin: current progress, challenges, and perspectives. Nutrients. 2018;10:pii–E1553. doi: 10.3390/nu10101553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal BB, Vijayalekshmi RV, Sung B. Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:425–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pahwa R, Jialal I. Chronic inflammation. StatPearls. 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493173 Available at. (accessed 11 June 2019) [PubMed]

- 7.Nojiri S, Daida H. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in Japan. Jpn Clin Med. 2017;8:1179066–017712713. doi: 10.1177/1179066017712713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frostegård J. Immunity, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. BMC Med. 2013;11:117. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao TX, Mallat Z. Targeting the immune system in atherosclerosis: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1691–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansson GK. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: the end of a controversy. Circulation. 2017;136:1875–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuda T. Curcumin as a functional food-derived factor: degradation products, metabolites, bioactivity, and future perspectives. Food Funct. 2018;9:705–14. doi: 10.1039/c7fo01242j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauf A, Imran M, Erdogan-Orhan I et al. Health perspective of a bioactive compound curcumin: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;74:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Zhu L, Gao X et al. Magnetic molecularly imprinted polymers for spectrophotometric quantification of curcumin in food. Food Chem. 2016;202:309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewlings SJ, Kalman DS. Curcumin: a review of its effects on human health. Foods. 2017;6:E92. doi: 10.3390/foods6100092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh S, Banerjee S, Sil PC. The beneficial role of curcumin on inflammation, diabetes and neurodegenerative disease: A recent update. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;83:111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willerson JT, Ridker PM. Inflammation as a cardiovascular risk factor. Circulation. 2004;109:II2-10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129535.04194.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochain C, Zernecke A. Macrophages in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:485–99. doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-1941-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsh P, Grassia G, Botha S et al. Targeting inflammation to reduce cardiovascular disease risk: a realistic clinical prospect? Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:3898–913. doi: 10.1111/bph.13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, Zou J, Li P et al. Curcumin protects against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice by inhibiting toll-like receptor 4 expression. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:449–56. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b04260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh SS, Righi S, Krieg R et al. High fat high cholesterol diet (Western diet) aggravates atherosclerosis, hyperglycemia and renal failure in nephrectomized LDL receptor knockout mice: role of intestine derived lipopolysaccharide. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frangogiannis NG. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:255–65. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nian M, Lee P, Khaper N et al. Inflammatory cytokines and postmyocardial infarction remodeling. Circ Res. 2004;94:1543–53. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000130526.20854.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lv FH, Yin HL, He YQ et al. Effects of curcumin on the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes and the expression of NF-ĸB, PPAR-γ and Bcl-2 in rats with myocardial infarction injury. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3877–84. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saeidinia A, Keihanian F, Butler AE et al. Curcumin in heart failure: A choice for complementary therapy? Pharmacol Res. 2018;131:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.201803.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang NP, Pang XF, suZhang LH et al. Attenuation of inflammatory response and reduction in infarct size by postconditioning are associated with downregulation of early growth response 1 during reperfusion in rat heart. Shock. 2014;41:346–54. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman AM, McNamara D. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fung G, Luo H, Qiu Y et al. Myocarditis. Circ Res. 2016;118:496–514. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fildes JE, Shaw SM, Yonan N et al. The immune system and chronic heart failure: is the heart in control? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yndestad A, Damås JK, Øie E et al. Role of inflammation in the progression of heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2007;9:236–41. doi: 10.1007/s11883-017-0660-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song Y, Ge W, Cai H et al. Curcumin protects mice from coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis by inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/Akt/nuclear factor-ĸB pathway. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2013;18:560–9. doi: 10.1177/1074248413503044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernández M, Wicz S, Corral RS. Cardioprotective actions of curcumin on the pathogenic NFAT/COX-2/prostaglandin E2 pathway induced during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:1392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao S, Zhou J, Liu N et al. Curcumin induces M2 macrophage polarization by secretion IL-4 and/or IL-13. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;85:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morimoto T, Sunagawa Y, Kawamura T et al. The dietary compound curcumin inhibits p300 histone acetyltransferase activity and prevents heart failure in rats. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:868–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI33160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saeidinia A, Keihanian F, Butler AE et al. Curcumin in heart failure: a choice for complementary therapy? Pharmacol Res. 2018;131:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1165–85. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su B, Liu T, Fan H et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sin DD, MacNee W. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular diseases: a “vulnerable” relationship. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:2–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1953ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moghaddam SJ, Barta P, Mirabolfathinejad SG et al. Curcumin inhibits COPD-like airway inflammation and lung cancer progression in mice. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1949–56. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan J, Liu R, Ma Y et al. Curcumin attenuates airway inflammation and airway remolding by inhibiting NF-ĸB signaling and COX-2 in cigarette smoke-induced COPD mice. Inflammation. 2018;41:1804–14. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0823-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Funamoto M, Sunagawa Y, Katanasaka Y et al. Highly absorptive curcumin reduces serum atherosclerotic low-density lipoprotein levels in patients with mild COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2029–34. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S104490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee H, Lee IS, Choue R. Obesity, inflammation and diet. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013;16:143–52. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2013.16.3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt FM, Weschenfelder J, Sander C et al. Inflammatory cytokines in general and central obesity and modulating effects of physical activity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim SH, Després JP, Koh KK. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: friend or foe? Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3560–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Y, Chen B, Shen J The beneficial effects of quercetin, curcumin, and resveratrol in obesity. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017. p. 1459497. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Pan Y, Zhao D, Yu N et al. Curcumin improves glycolipid metabolism through regulating peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ signalling pathway in high-fat diet-induced obese mice and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:170917. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ariamoghaddam AR, Ebrahimi-Hosseinzadeh B, Hatamian-Zarmi A et al. In vivo anti-obesity efficacy of curcumin loaded nanofibers transdermal patches in high-fat diet induced obese rats. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2018;92:161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jazayeri-Tehrani SA, Rezayat SM, Mansouri S et al. Nano-curcumin improves glucose indices, lipids, inflammation, and Nesfatin in overweight and obese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2019;16:8. doi: 10.1186/s12986-019-0331-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chuengsamarn S, Rattanamongkolgul S, Phonrat B et al. Reduction of atherogenic risk in patients with type 2 diabetes by curcuminoid extract: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Biochem. 2014;25:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panahi Y, Khalili N, Sahebi E et al. Curcuminoids modify lipid profile in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2017;33:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darweesh SKL, Wolters FJ, Ikram MA et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1450–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyss-Coray T, Rogers J. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease – a brief review of the basic science and clinical literature. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006346. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Justin BN, Turek M, Hakim AM. Heart disease as a risk factor for dementia. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:135–45. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S30621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seo EJ, Fischer N, Efferth T. Phytochemicals as inhibitors of NF-ĸB for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol Res. 2018;129:262–73. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu ZJ, Li ZH, Liu L et al. Curcumin attenuates beta-amyloid-induced neuroinflammation via activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma function in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:261. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Small GW, Siddarth P, Li Z et al. Memory and brain amyloid and tau effects of a bioavailable form of curcumin in non-demented adults: a double-blind, placebo-controlled 18-month trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:266–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adibian M, Hodaei H, Nikpayam O et al. The effects of curcumin supplementation on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, serum adiponectin, and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2019;33:1374–83. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krishnareddy NT, Thomas JV, Nair S et al. Corrigendum to “A novel curcumin-galactomannoside complex delivery system improves hepatic Function markers in chronic alcoholics: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study”. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5673740. doi: 10.1155/2019/5673740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohammadi F, Ghazi-Moradi M, Ghayour-Mobarhan M The effects of curcumin on serum heat shock protein 27 antibody titers in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Diet Suppl. 2018. pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Vors C, Couillard C, Paradis ME et al. Supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin does not affect the inflammatory response to a high-fat meal in older adults with abdominal obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Nutr. 2018;148:379–88. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxx072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Panahi Y, Khalili N, Sahebi E et al. Effects of curcuminoids plus piperine on glycemic, hepatic and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2018;68:403–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-101752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panahi Y, Alishiri GH, Parvin S et al. Mitigation of systemic oxidative stress by curcuminoids in osteoarthritis: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Diet Suppl. 2016;13:209–20. doi: 10.3109/19390211.2015.1008611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Panahi Y, Hosseini MS, Khalili N et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of curcuminoid-piperine combination in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial and an updated meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:1101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Usharani P, Mateen AA, Naidu MU et al. Effect of NCB-02, atorvastatin and placebo on endothelial function, oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, 8-week study. Drugs R D. 2008;9:243–50. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200809040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El-Naggar ME, Al-Joufi F, Anwar M et al. Curcumin-loaded PLA-PEG copolymer nanoparticles for treatment of liver inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019;177:389–98. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karri VV1, Kuppusamy G2, Talluri SV et al. Curcumin loaded chitosan nanoparticles impregnated into collagen-alginate scaffolds for diabetic wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;93:1519–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu Y, Li M, Zhang M et al. Inhalation treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with curcumin large porous microparticles. Int J Pharm. 2018;551:212–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qiao H, Fang D, Chen J et al. Orally delivered polycurcumin responsive to bacterial reduction for targeted therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Drug Deliv. 2017;34:233–42. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2016.1245367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Young NA, Bruss MS, Gardner M et al. Oral administration of nano-emulsion curcumin in mice suppresses inflammatory-induced NFĸB signaling and macrophage migration. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li X, Xiao H, Lin C et al. Synergistic effects of liposomes encapsulating atorvastatin calcium and curcumin and targeting dysfunctional endothelial cells in reducing atherosclerosis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:649–65. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S189819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]