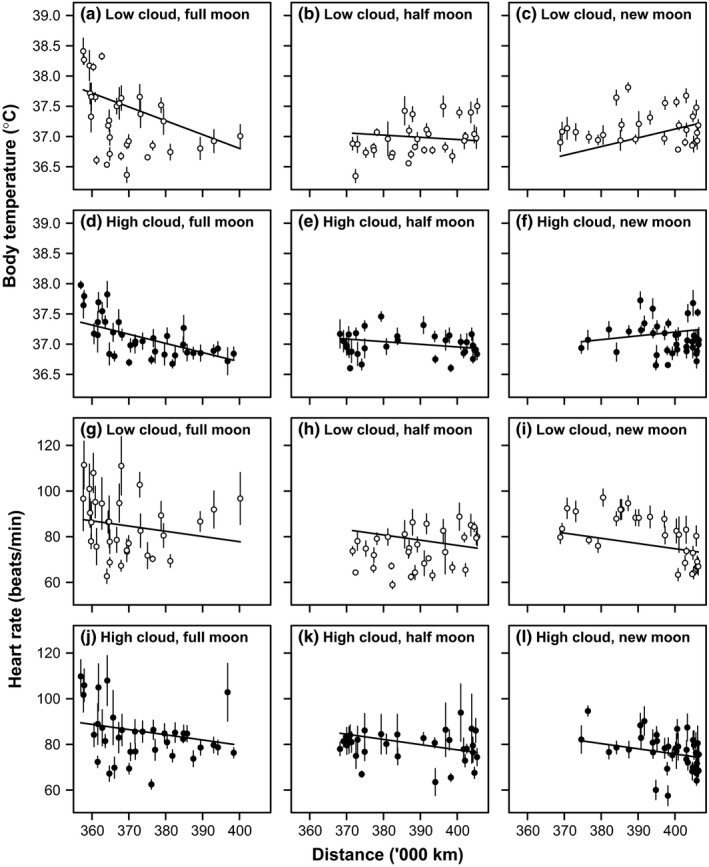

Figure 4.

The relationship between nighttime mean (a–f) body temperature and lunar distance, and (g–l) heart rate and lunar distance in six barnacle geese. To explore the significant three‐way interaction between the synodic lunar cycle, lunar distance, and cloud cover for body temperature (Table 1), the data are subdivided by cloud cover (<50%: a–c, g–i, unfilled symbols; ≥50%: d–f, j–l, filled symbols) and by synodic lunar cycle (Full moons: a, d, g, j, waxing or waning moons: b, e, h, k, new moons: c, f, i, l). For presentation, data points are adjusted for consistent inter‐individual differences and shown and mean ± SE, and moon phases were separated as follows: for full moons (a, d, g, j), phase angle in radians is within π/3 of full moon; for new moons (c, f, i, l), phase angle is within π/3 of a new moon; for waxing or waning moons (b, e, h, k), phase angles are intermediate. Solid lines are derived from parameter estimates for the full model (Table 1) for heart rate, calculated for a cloud cover of 0% for low cloud (a–c) and 100% for high cloud (d–f) and for a full moon (a, d), half‐moon (b, e), or new moon (c, f). For body temperature, parameter estimates are calculated for a reduced model excluding two‐ and three‐way interactions that are nonsignificant in Table 2, calculated for a cloud cover of 0% for low cloud (g–i) and 100% for high cloud (j–l) and for a full moon (g, j), half‐moon (h, k), or new moon (i, l)