Abstract

The neurotransmitter noradrenaline (NA) can provide neuroprotection against insults including inflammatory stimuli and excitotoxicity, which may involve paracrine effects of neighboring glial cells. Astrocytes express and secrete a variety of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory molecules; however, the effects of NA on astrocyte chemokine expression have not been well characterized. In primary astrocytes, NA increased expression of chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) at the mRNA and protein levels. NA increased activation of an MCP-1 promoter driving luciferase expression, which was replicated by β-adrenergic receptor agonists and a cAMP analog, and blocked by a specific β2-adrenergic receptor antagonist. In primary neurons, addition of MCP-1 reduced NMDA-dependent glutamate release as well as glutamate-dependent Ca2+ entry. Similarly, conditioned media from NA-treated astrocytes reduced glutamate release, an effect that was blocked by neutralizing antibody to MCP-1, whereas MCP-1 dose-dependently reduced neuronal damage attributable to NMDA or to glutamate. MCP-1 significantly reduced lactate dehydrogenase release from neurons after oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD) and prevented the loss of ATP levels that occurred after OGD or treatment with glutamate. Incubation of neurons with astrocytes separated by a membrane to prevent physical contact showed that NA induced astrocyte release of sufficient MCP-1 to reduce neuronal damage attributable to OGD. These findings indicate that the neuroprotective effects of NA are mediated, at least in part, by induction and release of astrocyte MCP-1.

Keywords: chemokines, glia, cAMP, glutamate, NMDA, ischemia

Introduction

Accumulating data demonstrate that the neurotransmitter noradrenaline (NA) can reduce damage during neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative conditions. In vitro studies have shown that NA suppresses glial expression of proinflammatory cytokines and the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Feinstein et al., 1993; Dello Russo et al., 2004). Similarly, in vivo studies show that experimental depletion of brain NA exacerbates inflammatory responses (Heneka et al., 2002), whereas increasing NA levels reduces inflammation (Kalinin et al., 2006) and provides neuroprotection (Troadec et al., 2002).

After activation by inflammatory stimuli, glial cells express and release a variety of substances which regulate the overall inflammatory milieu. Although anti-inflammatory treatments often modify gene transcription within target cells, changes in expression or production of paracrine factors could dampen or potentiate ongoing responses. In this regard, we showed that although conditioned media (CM) from activated microglia induces iNOS expression in neurons, that induction was lost if the microglia were cotreated with NA (Madrigal et al., 2005).

During studies to understand the ability of NA to reduce microglial inflammation, we observed that the secreted factors most affected by NA were cytokine IL-12p40 subunit and chemokine MIP-1α (Douglas L. Feinstein and Jose L. M. Madrigal, unpublished observations). Because both these molecules are regulated by chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein) (Luther and Cyster, 2001), we tested if NA regulated glial MCP-1 expression. We show here that NA increases MCP-1 expression in astrocytes, and that astrocyte-derived MCP-1 is neuroprotective against excitotoxic damage attributable to NMDA or glutamate, or which occurs during oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD).

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Cell culture reagents (DMEM and antibiotics) were from Cellgro Mediatech. Fetal calf serum (FCS) (<10 EU endotoxin per ml), neurobasal medium (NBM), B27 supplements, and DMEM-F12 were from Invitrogen. NA, dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP), propranolol, and NMDA were from Sigma. Recombinant MCP-1 was from PeproTech. Antibody against MCP-1 was from Abcam.

Cells.

Rat cortical microglia and astrocytes were obtained as described previously (Vairano et al., 2002). Briefly, 1-d-old Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) were used to prepare primary mixed glial cultures; microglia were detached by gentle shaking after 11–13 d in culture and then replated into 96-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/cm2 and were 95–98% OX-42-positive. Astrocytes were prepared by mild trypsinization of the remaining cells, replated at 5 × 105 cells per 35 mm plate and consisted of >95% astrocytes as determined by staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein and <5% microglial as determined by staining for OX-42.

Primary cultures of cortical neurons were prepared as described previously (Madrigal et al., 2005). In brief, brains were removed from embryonic day 16 Sprague Dawley rat pups, cortical areas dissected, neurons mechanically dissociated in 80% Basal Medium Eagle containing 33 mm glucose, 2 mm glutamine, 16 mg/l gentamicin, 10% horse serum, and 10% FCS, and plated at 2 × 105 cells/cm2 in poly-l-lysine-precoated plates. The medium was replaced 24 h later with serum-free NBM supplemented with 0.5 mmol/l-glutamine and complete B27, and 4 d later, 50% of the medium was replaced with fresh NBM. Neurons were grown for 9–10 d in NBM, at which point 98 ± 2% of the cells stained positively for neuronal marker neuronal-specific nuclear protein. At that time, the media was removed, neurons washed once gently in fresh NBM to remove any lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) that accumulated during the growth period, and test substances added in fresh NBM supplemented with 0.5 mmol/l-glutamine and B27 without antioxidants.

Cell viability.

Neuronal viability was assessed by measurement of released LDH, using the CytoTox-96 kit from Promega according to manufacturer's instructions.

mRNA analysis.

Total cytoplasmic RNA was prepared using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), aliquots converted to cDNA, and mRNA levels estimated by quantitative real-time PCR (QPCR). The primers for β-actin were as follows: forward: 5′-CCTGAAGTACCCCATTGAACA, reverse: 5′-CACACGCAGCTCATTGTAGAA-3′; MCP-1: forward: 5′-TGCTGTCTCAGCCAGATGCAGTTA-3′, reverse: 5′-TACAGCTTCTTTGGGACACCTGCT-3′. PCR conditions were 35 cycles at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 60°C for 15 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s followed by 5 min at 72°C in a Corbett Rotorgene. Relative mRNA levels were calculated by comparison of take off cycles and normalized to values for β-actin measured in the same samples.

Plasmid constructs.

The MCP-1 promoter region was isolated as described previously (Kutlu et al., 2003) from rat genomic DNA. The primers used were as follows: forward (position −515 to −499): 5′-AGCGAGCTCAAGCTCTTCGGTTTGG-3′ with an added SacI site, reverse (position +31 to +53): 5′-CGGGATCCGGCTTCAGTGAGAG-3′ with an added BamHI site. The product was purified, digested with SacI and BamH1, and the insert subcloned into the SacI-BglII sites of pGL2-Basic (Promega) to obtain pMCP1-luc construct.

Exposure of neuronal cultures to OGD.

Primary neurons were preincubated with varying concentrations of MCP-1 for 24 h then exposed to 150 min of OGD as described previously (De Cristóbal et al., 2002). Culture medium was replaced by a solution (OGD media) containing 130 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 26 mm NaHCO3, 0.8 mm MgCl2, 1.18 mm NaH2PO4, and 2% horse serum bubbled with 95% N2/5% CO2. The neurons were transferred to an anaerobic chamber (Forma Scientific) containing a mixture of 95%N2/5%CO2 humidified at 37°C. OGD was terminated by replacing the OGD medium with serum-free NBM supplemented with 0.5 mm glutamine and complete B27 and cells returned to normoxia. Control cultures were treated the same as OGD samples but in OGD solution containing 33 mm glucose.

Astrocyte–neuron cocultures.

Astrocytes were replated by seeding 130,000 viable cells onto 0.33 cm2 Transwell cell-culture inserts (Corning Life Sciences) with a pore size of 0.4 μm, which allows traffic of small, diffusible substances but prevents cell contact. A transient coculture was initiated by transferring inserts into 24-well plates containing primary neurons of culture age 9–10 d. At that point, the cocultures were treated with nothing, 10 μm NA, or 10 μm NA plus 10 μg/ml of neutralizing antibody to MCP-1. After 24 h, astrocytes were removed, culture media changed to OGD media, neurons exposed to OGD, and damage assessed 24 h later.

Transfection and transient expression assay.

Primary astrocytes were transfected with 0.2 μg pMCP1-luc plasmid and 0.2 μg empty phRG-TK renilla luciferase vector (Promega) using Effectene reagent according to instructions. After 48 h, cells were exposed to various treatments for 4 h. Luciferase assays were performed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter System (Promega), luminescence measured in a Zylux Femtomaster FB12 luminometer, and the ratio between firefly and renilla luciferase luminescence determined.

MCP-1 measurement.

MCP-1 levels in the medium were detected using a specific ELISA for rat MCP-1, according to manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems).

Measurement of extracellular glutamate.

Glutamate concentrations in media were determined spectrophotometrically as the increase in NADH fluorescence after conversion of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate, using a commercially available kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Measurement of ATP levels.

ATP concentrations were measured with a firefly luciferin–luciferase assay-based commercial kit following manufacturer instructions (Thermo Labsystems).

Relative intracellular calcium measurement.

Primary neurons were treated for 24 h with varying concentrations of MCP-1, preloaded with Fluo-4 A.M. (10 μm; Invitrogen) for 60 min and then rinsed three times with PBS. Before recording, the medium was exchanged for modified HBSS containing 137 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 3 mm NaHCO3, 0.6 mm Na2HPO4, 0.4 mm KH2PO4, 1.4 mm CaCl2, 0.8 mm MgSO4, 20 mm HEPES, 5.6 mm glucose, and 5 μm glycine, pH 7.4. After baseline fluorescence was obtained, 0 or 200 μm glutamate (alone or with 10 μm of the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801) was added and fluorescence recorded 3 min later using the Fluoroscan Ascent reader (Labsystems).

Data analysis.

All experiments were done at least in triplicate. Data were analyzed by unpaired t tests, and p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Noradrenaline increases MCP-1 expression in astrocytes

Treatment with NA significantly increased MCP-1 mRNA levels in primary astrocytes but reduced levels in primary microglia (Fig. 1A). NA increased astrocyte release of MCP-1 (Fig. 1B) and increased activation of an MCP-1 promoter driving luciferase expression (Fig. 1C). The MCP-1 promoter was activated by the cAMP analog dbcAMP and by a selective β-adrenergic (βAR) agonist. The effect of NA was dose-dependently reduced by coincubation with the nonselective βAR antagonist propranol and by a selective β2AR antagonist (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Noradrenaline increases MCP-1 in astrocytes. A, Enriched cultures of astrocytes (Ast) or microglia (μGlia) were incubated with 0 or 10 μm NA for 24 h, then MCP-1 mRNA levels measured by QPCR. Data are mean ± SE of MCP-1 mRNA levels normalized to values for β-actin and are expressed relative to control (100%) values. **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001 versus control; n = 8 replicates per group. B, Astrocytes were incubated with 0–25 μm NA, and MCP-1 levels in the media were assessed after 24 h by ELISA. Data are means ± SE of n = 8 replicates per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0005 versus control. C, Astrocytes were transfected with an pMCP-1 luc reporter (0.2 μg) and Renilla control phRG-TK vector. After 24 h, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of NA, dbcAMP, or the β-AR agonist Isoproterenol, or (D) 10 μm NA together with varying concentration of the β-AR agonist propranolol or the β2-AR agonist ICI118551. MCP-1 promoter activity was measured after 4 h, and differences in transfection efficiencies were corrected for by normalization to renilla luciferase activity. The data are mean ± SE of n = 3–4 replicates and are relative to the MCP-1 activity measured in nontreated cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 versus control values.

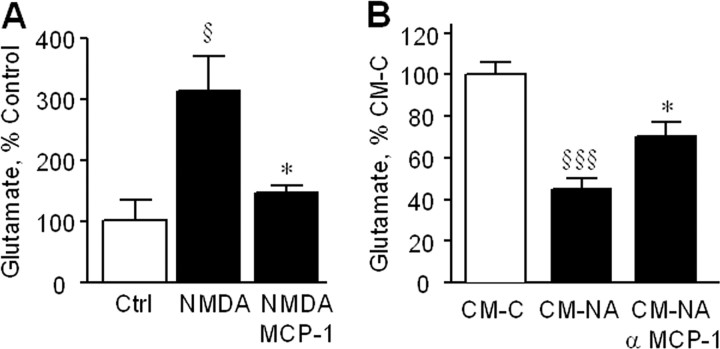

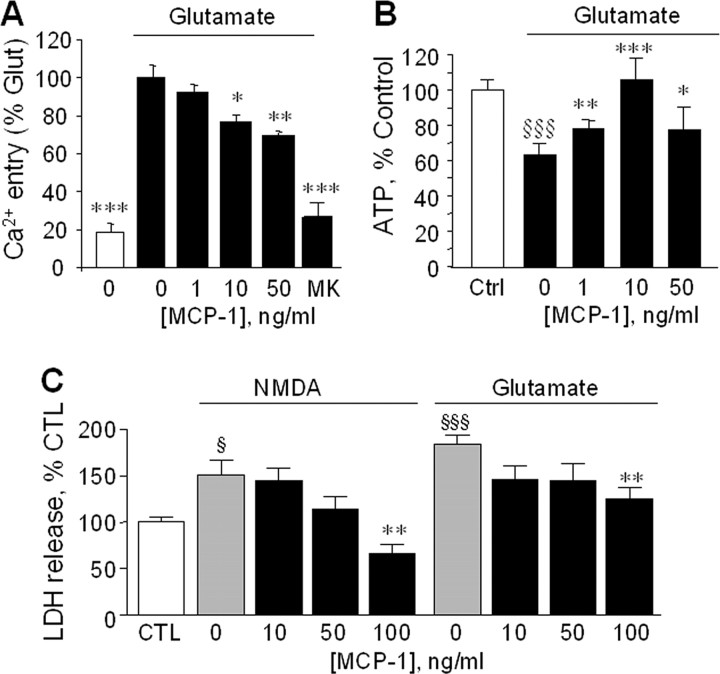

MCP-1 reduces glutamate release from and Ca2+ entry into neurons

Exposure of primary cortical neurons to NMDA induced significant glutamate release (Fig. 2A) that was reduced to near control levels by MCP-1. Similarly, cotreatment with CM generated from NA-treated astrocytes reduced NMDA-dependent glutamate release (Fig. 2B), and that reduction was attenuated by a neutralizing antibody to MCP-1. Glutamate induced a rapid increase in intracellular Ca2+ in neurons, which was dose-dependently reduced by pretreatment with MCP-1 (Fig. 3A). Ca2+ entry was almost completely blocked by MK801, indicating that the majority of the Ca2+ measured entered neurons via NMDA receptors. Glutamate caused a significant decrease in neuronal ATP levels, which was attenuated by pretreatment with MCP-1 (Fig. 3B). MCP-1 dose-dependently reduced neuronal cell death after incubation with NMDA or glutamate (Fig. 3C), consistent with its ability to reduce glutamate release and Ca2+ entry.

Figure 2.

MCP-1 decreases extracellular glutamate. A, Primary neurons were incubated with NMDA (20 μm) in the presence or absence of MCP-1 (10 ng/ml), and after 48 h, the extracellular concentration of glutamate was determined. The data are mean ± SE of n = 10 replicates and is shown relative to values measured in control (Ctrl) cells (100% = 40.5 ± 0.7 μm) §p < 0.05 versus control, *p < 0.05 versus NMDA. B, Primary neurons were incubated with NMDA (20 μm) in the presence of conditioned media from astrocytes treated without (CM-C) or with (CM-NA) NA (75 μm) for 24 h and in the absence or presence of a neutralizing antibody against MCP-1 (10 μg/ml). After 48 h, the extracellular concentration of glutamate was determined. The data are mean ± SE of n = 10 replicates and is shown relative to values measured in CM-C cells (100% = 40.5 ± 0.7 μm) §§§p < 0.0005 versus CM-C, *p < 0.05 versus CM-NA.

Figure 3.

MCP-1 reduces excitotoxicity. A, Primary neurons were treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of MCP-1, then preloaded with Fluo-4 A.M. and incubated with glutamate (200 μm). As a control neurons were incubated with glutamate together with the NMDA-R antagonist MK801 (“MK,” 10 μm). The fluorescence signal was measured after 3 min. The data are mean ± SE of n = 12 replicates and is Ca2+ entry relative to that measured in the presence of glutamate alone. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0001 versus glutamate alone. B, Primary neurons were incubated with 0 (Ctrl) or 200 μm glutamate and the indicated concentrations of MCP-1, and the cellular ATP levels were measured 24 h later. Data are mean ± SE of n = 12 replicates and is the ATP level relative to control cells. §§§p < 0.0001 versus control; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0001 versus no MCP-1. C, Primary neurons were incubated with NMDA (20 μm) or glutamate (100 μm) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of MCP-1. After 48 h, neuronal viability was assessed by measurement of LDH in the media. Data are mean ± SE of n = 8 replicates and is the LDH released compared with control (CTL; nontreated cells). §p < 0.05 versus control; §§§p < 0.0005 vs control; **p < 0.005 versus NMDA alone or versus glutamate alone. In control cells, 100% LDH reflected 20 ± 1.4% of total LDH released after 48 h (mean ± SE of n = 15 individual measurements).

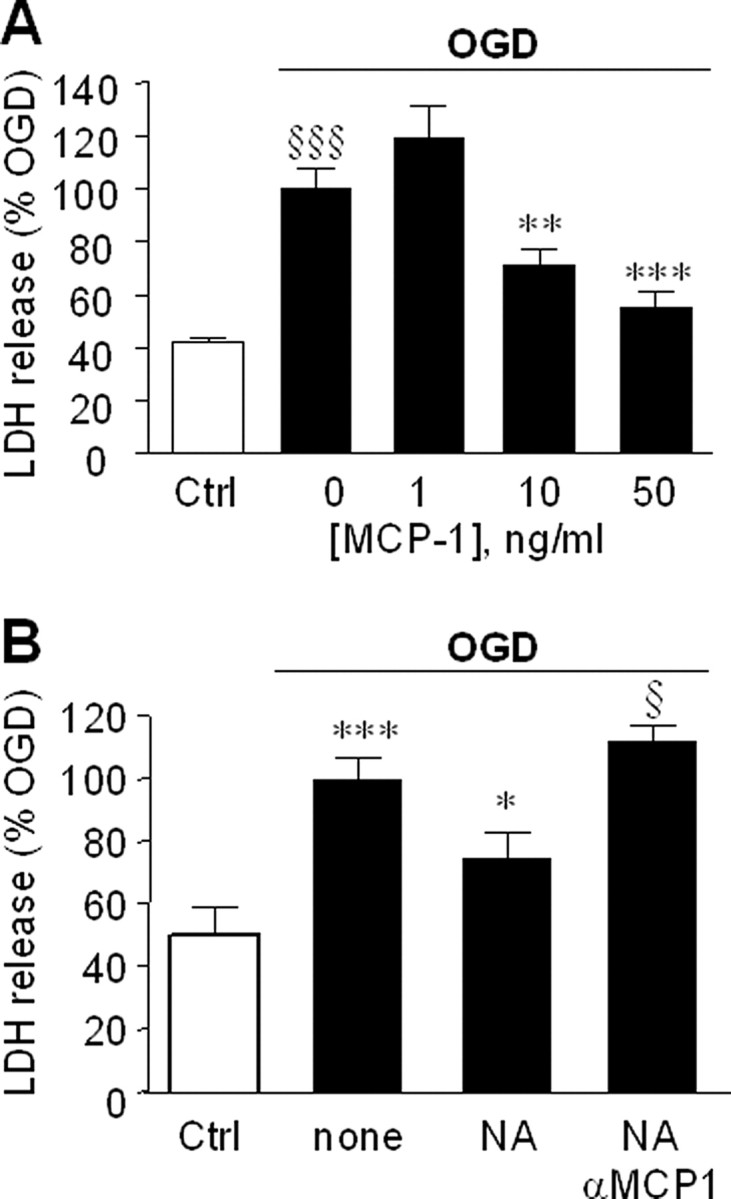

MCP-1 protects neurons against damage attributable to oxygen–glucose deprivation

Exposure of primary neurons to OGD caused a significant increase in cell death as measured by LDH release which was increased ∼2.5-fold by OGD and was significantly reduced by incubation with 10 or 50 ng/ml MCP-1 (Fig. 4A). To determine if astrocyte-derived MCP-1 provided neuroprotection, we tested effects of astrocyte-conditioned media on OGD-induced damage (Fig. 4B). Neurons were preincubated for 24 h in the presence of astrocytes separated by a transwell membrane that allowed for transfer of soluble factors while preventing direct contact, after which the astrocytes were removed, the media changed, and the neurons subjected to OGD. When preincubated with astrocytes, there was significant LDH release after OGD compared with neurons kept under normoxic conditions. However, when preincubation was done in the presence of NA, there was a significant reduction of subsequent OGD-dependent LDH release, and this reduction was reversed by the presence of neutralizing antibody to MCP-1. Preincubation of neurons with NA alone in the absence of astrocytes did not reduce OGD-dependent LDH release (data not shown).

Figure 4.

MCP-1 reduces ischemic damage. A, Primary neurons were preincubated with the indicated concentrations of MCP-1 for 24 h, then exposed to OGD or kept under normoxic conditions [control (Ctrl); open bar], after which the media was replaced with fresh media (containing the same amounts of MCP-1). Neuronal viability was assessed 48 h later by measurement of LDH release. Data are mean ± SE of n = 12 replicates and shown relative to LDH release attributable to OGD alone. §§§p < 0.0005 versus control cells; **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0001 versus OGD. B, Primary astrocytes growing on transwell membranes were transferred to wells containing primary neurons. After 24 h, the cocultures were treated for a further 24 h with fresh media (none), 10 μm NA (NA), or 10 μm NA and 10 μg/ml of MCP-1 neutralizing antibody (NA+αMCP1). After treatment, the astrocytes were removed, the media replaced, the neurons were exposed OGD, and neuronal viability assessed after 24 h. Control neurons (Ctrl; open bar) were kept normoxic. The data are the mean ± SE on n = 8 replicates and is LDH release relative to OGD treated only cells. ***p < 0.0005 versus control cells; *p < 0.05 versus none; §p < 0.05 versus NA. In control cells, 100% LDH reflected 20 ± 1.4% of total LDH released after 48 h (mean ± SE of n = 15 individual measurements).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that NA induces expression of MCP-1 in astrocytes, which is neuroprotective against excitotoxic-dependent damage. In primary neurons, MCP-1 reduced NMDA-dependent glutamate release, glutamate-dependent Ca2+ entry and ATP loss, and LDH release attributable to NMDA or glutamate. MCP-1 also reduced the toxic consequences of OGD in neurons, as did conditioned media from astrocytes which could be prevented by a blocking antibody to MCP-1. These data demonstrate that neuroprotective effects of NA are mediated in part by release of neuroprotective chemokines such as MCP-1 from neighboring astrocytes.

The ability of NA or of its downstream messenger cAMP to regulate astrocyte MCP-1 expression has not been well characterized. Similar to our findings, treatment of astrocytes with dbcAMP increased MCP-1 release (Tawfik et al., 2006), and in non-neural cells, NA increased MCP-1 in rat aorta (Capers et al., 1997) and in mouse peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Takahashi et al., 2004). In contrast, elevation of cAMP levels in microglia reduced MCP-1 expression (Delgado et al., 2002), suggesting differences between peripheral blood mononuclear cells (which include macrophages) and CNS-derived microglia. We show that NA acts at the transcriptional level because activation of a 570 bp MCP-1 promoter construct was increased by NA as well as by the βAR agonist isoproterenol and by dbcAMP. Although the cloned MCP-1 promoter region had the expected size, the product was not sequenced, and, therefore, introduction of point mutations may have influenced its responses. The rodent MCP-1 promoter region contains conserved binding sites for several cAMP-responsive transcription factors including AP-1, C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein), and cAMP response element-binding protein, suggesting these as targets of NA effects. MCP-1 can also be induced in glial cells upon NFκB activation (Thibeault et al., 2001); therefore, the ability of NA to induce MCP-1 could involve NFκB activation. Our observations that NA does not increase MCP-1 mRNA in enriched microglia support that NA effects are primarily mediated via astrocytes.

Our data suggests that MCP-1 reduces the ability of neuronal NMDA receptors to respond to ligand, thereby reducing glutamate release and subsequent effects. Consistent with this, MCP-1 has been shown to inhibit NMDA-induced increases in extracellular glutamate, as well as NMDA-dependent increase in NMDA-R1 expression (Eugenin et al., 2003), and to reduce NMDA-dependent death in mixed cortical cultures (Bruno et al., 2000). It is also possible that MCP-1 increases the ability of astrocytes present to uptake glutamate through selective transporters (Gochenauer and Robinson, 2001); however, because NMDA is a poor substrate for these transporters (Schurr et al., 1999), astrocyte removal alone is unlikely to explain the overall neuroprotective effects of MCP-1. Finally, although MCP-1 reduced frank neuronal death caused by OGD, this does not rule out that surviving neurons were damaged to a lesser extent.

Our studies suggest that the neuroprotective effects of MCP-1 are mediated via activation of MCP-1 receptors (CCR2) on neurons. Although CCR2 expression has mainly been described in glia, several studies report constitutive as well as inducible neuronal expression (for a recent review, see Melik-Parsadaniantz and Rostene, 2008). Neuronal CCR2 has been detected on hippocampal neurons in brain sections obtained from both HIV as well as non-HIV patients (van der Meer et al., 2000) and is expressed on primary neurons derived from fetal human brain (Coughlan et al., 2000). In rats, constitutive neuronal CCR2 was found in several regions of normal adult brain including on dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons (Banisadr et al., 2005), cerebellar Purkinje neurons (van Gassen et al., 2005), and spinal cord neurons (Gosselin et al., 2005). Neuronal CCR2 expression is increased in several injury models, including on dorsal root ganglion neurons after neuropathic pain (White et al., 2005) and in sensory neurons after focal demyelination (Jung et al., 2008), suggesting that neuronal CCR2 expression may be increased under excitotoxic conditions.

High glutamate levels in brain occur in chronic neurodegenerative conditions including Alzheimer's disease (Lipton, 2005) and Parkinson's disease (Hallett and Standaert, 2004) and also by acute events including stroke (Castillo et al., 1996) and traumatic brain injury (Zauner et al., 1996). Excessive glutamate causes influx of large amounts of Ca2+ into neurons, which damages mitochondria and promotes synthesis of proapoptotic genes, eventually resulting in neuronal death (Stout et al., 1998). The use of drugs able to block excessive stimulation of NMDA receptors without interfering with the physiological functions of NMDA has proven to be an efficacious therapy against Alzheimer's disease. Our data suggest that selective increases in chemokines such as MCP-1 might also provide a means to reduce glutamate induced damage.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Merit grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, and grants from the Spanish Ministries of Education and Science (SAF2007-63138) and Health (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red en Salud Mental) (J.L.M.M., J.C.L.).

References

- Banisadr G, Gosselin RD, Mechighel P, Rostène W, Kitabgi P, Mélik Parsadaniantz S. Constitutive neuronal expression of CCR2 chemokine receptor and its colocalization with neurotransmitters in normal rat brain: functional effect of MCP-1/CCL2 on calcium mobilization in primary cultured neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:178–192. doi: 10.1002/cne.20729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno V, Copani A, Besong G, Scoto G, Nicoletti F. Neuroprotective activity of chemokines against N-methyl-D-aspartate or beta-amyloid-induced toxicity in culture. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;399:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capers Q, 4th, Alexander RW, Lou P, De Leon H, Wilcox JN, Ishizaka N, Howard AB, Taylor WR. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic tissues of hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;30:1397–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo J, Dávalos A, Naveiro J, Noya M. Neuroexcitatory amino acids and their relation to infarct size and neurological deficit in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1996;27:1060–1065. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.6.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan CM, McManus CM, Sharron M, Gao Z, Murphy D, Jaffer S, Choe W, Chen W, Hesselgesser J, Gaylord H, Kalyuzhny A, Lee VM, Wolf B, Doms RW, Kolson DL. Expression of multiple functional chemokine receptors and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human neurons. Neuroscience. 2000;97:591–600. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cristóbal J, Madrigal JL, Lizasoain I, Lorenzo P, Leza JC, Moro MA. Aspirin inhibits stress-induced increase in plasma glutamate, brain oxidative damage and ATP fall in rats. Neuroreport. 2002;13:217–221. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200202110-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Jonakait GM, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit chemokine production in activated microglia. Glia. 2002;39:148–161. doi: 10.1002/glia.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dello Russo C, Boullerne AI, Gavrilyuk V, Feinstein DL. Inhibition of microglial inflammatory responses by norepinephrine: effects on nitric oxide and interleukin-1beta production. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenin EA, D'Aversa TG, Lopez L, Calderon TM, Berman JW. MCP-1 (CCL2) protects human neurons and astrocytes from NMDA or HIV-tat-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1299–1311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein DL, Galea E, Reis DJ. Norepinephrine suppresses inducible nitric oxide synthase activity in rat astroglial cultures. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1945–1948. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gochenauer GE, Robinson MB. Dibutyryl-cAMP (dbcAMP) up-regulates astrocytic chloride-dependent L-[3H]glutamate transport and expression of both system xc(-) subunits. J Neurochem. 2001;78:276–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin RD, Varela C, Banisadr G, Mechighel P, Rostene W, Kitabgi P, Melik-Parsadaniantz S. Constitutive expression of CCR2 chemokine receptor and inhibition by MCP-1/CCL2 of GABA-induced currents in spinal cord neurones. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1023–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett PJ, Standaert DG. Rationale for and use of NMDA receptor antagonists in Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;102:155–174. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Galea E, Gavriluyk V, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Daeschner J, O'Banion MK, Weinberg G, Klockgether T, Feinstein DL. Noradrenergic depletion potentiates β-amyloid-induced cortical inflammation: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2434–2442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02434.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Toth PT, White FA, Miller RJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 functions as a neuromodulator in dorsal root ganglia neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;104:254–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinin S, Polak PE, Madrigal JL, Gavrilyuk V, Sharp A, Chauhan N, Marien M, Colpaert F, Feinstein DL. Beta-amyloid-dependent expression of NOS2 in neurons: prevention by an alpha2-adrenergic antagonist. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:873–883. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu B, Darville MI, Cardozo AK, Eizirik DL. Molecular regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2003;52:348–355. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA. The molecular basis of memantine action in Alzheimer's disease and other neurologic disorders: low-affinity, uncompetitive antagonism. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:155–165. doi: 10.2174/1567205053585846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther SA, Cyster JG. Chemokines as regulators of T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:102–107. doi: 10.1038/84205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal JL, Feinstein DL, Dello Russo C. Norepinephrine protects cortical neurons against microglial-induced cell death. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:390–396. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mélik-Parsadaniantz S, Rostène W. Chemokines and neuromodulation. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;198:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr A, Miller JJ, Payne RS, Rigor BM. An increase in lactate output by brain tissue serves to meet the energy needs of glutamate-activated neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:34–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00034.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout AK, Raphael HM, Kanterewicz BI, Klann E, Reynolds IJ. Glutamate-induced neuron death requires mitochondrial calcium uptake. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:366–373. doi: 10.1038/1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Tsuda Y, Kobayashi M, Herndon DN, Suzuki F. Increased norepinephrine production associated with burn injuries results in CCL2 production and type 2 T cell generation. Burns. 2004;30:317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik VL, Lacroix-Fralish ML, Bercury KK, Nutile-McMenemy N, Harris BT, Deleo JA. Induction of astrocyte differentiation by propentofylline increases glutamate transporter expression in vitro: heterogeneity of the quiescent phenotype. Glia. 2006;54:193–203. doi: 10.1002/glia.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibeault I, Laflamme N, Rivest S. Regulation of the gene encoding the monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) in the mouse and rat brain in response to circulating LPS and proinflammatory cytokines. J Comp Neurol. 2001;434:461–477. doi: 10.1002/cne.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troadec JD, Marien M, Mourlevat S, Debeir T, Ruberg M, Colpaert F, Michel PP. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK(1/2)) signaling pathway by cyclic AMP potentiates the neuroprotective effect of the neurotransmitter noradrenaline on dopaminergic neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1043–1052. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vairano M, Dello Russo C, Pozzoli G, Battaglia A, Scambia G, Tringali G, Aloe-Spiriti MA, Preziosi P, Navarra P. Erythropoietin exerts anti-apoptotic effects on rat microglial cells in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:584–592. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer P, Ulrich AM, Gonźalez-Scarano F, Lavi E. Immunohistochemical analysis of CCR2, CCR3, CCR5, and CXCR4 in the human brain: potential mechanisms for HIV dementia. Exp Mol Pathol. 2000;69:192–201. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2000.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gassen KL, Netzeband JG, de Graan PN, Gruol DL. The chemokine CCL2 modulates Ca2+ dynamics and electrophysiological properties of cultured cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2949–2957. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FA, Sun J, Waters SM, Ma C, Ren D, Ripsch M, Steflik J, Cortright DN, Lamotte RH, Miller RJ. Excitatory monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 signaling is up-regulated in sensory neurons after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14092–14097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503496102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauner A, Bullock R, Kuta AJ, Woodward J, Young HF. Glutamate release and cerebral blood flow after severe human head injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1996;67:40–44. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6894-3_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]