Abstract

Attachment is a pattern of interaction and communication established and developed between mother and baby. For the growth of mentally and physically healthy individuals, the mother is expected to create a suitable attachment starting before the birth and to maintain it afterwards. It is also necessary for the baby to establish appropriate and safe attachment towards the mother in a similar manner. There are several factors that affect the attachment. Also, some studies show that children with attachment problems also have problems in their future lives. Healthcare professionals need to be aware of these factors and evaluate the child in terms of healthy parental communication and child development in well-child visits. As a result of these evaluations, multidisciplinary approaches to the mother-child pair can be established and the child’s health is protected mentally and physically for healthy generations.

Keywords: Attachment, infant, mother

Abstract

Bağlanma, anne ve bebeği arasında her iki yönde gelişen ve kurulan bir iletişim ve etkileşim örüntüsüdür. Ruhen ve bedenen sağlıklı bireylerin yetişmesi için, annenin bebeği ile doğum öncesinden başlayan ve doğum sonrası da devam eden uygun bağlanma oluşturması ve sürdürmesi beklenirken, benzer şekilde bebeğin de annesi ile uygun ve güvenli bağlanma kurması gerekmektedir. Bağlanmayı etkileyen birçok etmen bulunmaktadır. Bağlanmada sorun yaşayan çocukların ileriki yaşamlarında sorunlar olduğunu gösteren çalışmalar da bulunmaktadır. Sağlık çalışanlarının, bu etmenlerin farkında olması ve sağlıklı çocuk izlemlerinde, çocuğu sağlıklı ebeveyn iletişimi ve gelişimi açısından değerlendirilmesi gerekmektedir. Bu değerlendirme sonucunda, anne-çocuk ikilisine çok disiplinli yaklaşımlar yapılabilir ve sağlıklı nesiller için çocuğun sağlığı ruhen ve bedenen korunmuş olur.

Introduction

Definition and importance of attachment

The humans are gregarious organisms because of their will to be together with other humans. In contrast to the offspring of other living creatures, the children of human beings need the direct help of their parents and other people who take care of them for a much longer time in order to survive due to their special biologic status. The requirement for meeting these needs has caused the need for attachment to caregivers for human babies. Attachment is a process that starts with the birth of the baby and is expected to occur, and its emotional aspect predominates (1). Two different terms are used in English for this concept, which has two directions, including the attachment of the mother to the baby and the attachment of the baby to the mother; the interaction and attachment of the mother with her baby is named ‘bonding’ and the attachment of the baby to their mother is named ‘attachment’ (2). In our language (Turkish), these two terms are not named differently and the word ‘bağlanma’ is used for both. These two attachments are related with each other, but the concept of ‘attachment’ used in this article involves the concept of ‘attachment,’ which is the attachment of the baby to its mother.

The mother’s level of attachment to her baby influences the baby’s attachment to its mother. The presence of early social interaction between the caregiver and the baby affects the baby’s cognitive and socio-emotional development. With this influence, the baby may adjust its social, familial, and romantic relations positively or negatively in later life (3). The baby’s attachment behavior is regarded to be the result of the emotions including alienation, disease, distress, hunger, danger, and fear, which activate the attachment system and are triggered environmentally and internally (4, 5). With these experiences, babies mature against these threats and develop physical and mental protection methods to maintain their safety and life (6).

Attachment is defined as a consistent and chronic emotional link that mainly emerges in cases of anxiety-tension in the relationship between the child and the person who cares for the child (7). According to Kavlak (8), it is a feeling of confidence that occurs as a result of repeated positive mother-baby relationship. The thought that “the quality of the relationship established with the attachment figure or the primary caregivers in younger ages constitutes the basis for the close relations in later years of life” is the psychanalytic theory (9). Bowlby (5) proposed that the mental samples established by the child in relation to themselves and the caregiver on the basis of the stimuli and reactions given to the child by the caregiver in the process of growth, are unchangeable for a lifetime and determine the quality of interpersonal relations in all periods. It has been claimed that the child’s chance of survival increases and protection against evolutionary life-threatening states is provided with this attachment.

Clinical and Research Effects

Attachment patterns in infancy and childhood

One of the people who gave the most important contribution to Bowlby’s theory was Ainsworth who evaluated babies’ reactions to different states using the “Strange Situation Test,” which Ainsworth developed in a study conducted in Ugandan mothers and babies. In this test, it was recorded how the baby behaved in a new environment when they were alone, when their mother was present in the room and when a stranger was present in seven steps that continued for three minutes each, and what kind of reactions they gave when their mother returned to the room. As a result of this study, three types of attachment patterns were defined; ‘secure,’ ‘insecure/resistant,’ and ‘insecure/avoidant’ (10). Later, the ‘disorganized (dispersed)’ attachment pattern was added to these three patterns by Main and Solomon (11). It was found that children with the secure attachment pattern had the will to explore and discover when they entered the room with their mothers, experienced anxiety and tension when their mothers left the room, and rapidly relaxed when their mothers came back to the room and again had the will to explore and share what they discovered. It was observed that children who had the insecure/resistant attachment pattern discontinued exploring and playing when their mothers left the room, experienced intense anxiety and emotional tension and their emotional tension did not reduce and they could not calm down even if their mothers came back into the room. It was found that the children with the insecure/resistant attachment pattern kept away from the mother and resisted the mother’s efforts to communicate when they returned. Babies with the insecure/disorganized attachment pattern display surprised, anxious, and inattentive behaviors and go to their mothers looking in different directions (12).

Factors influencing attachment

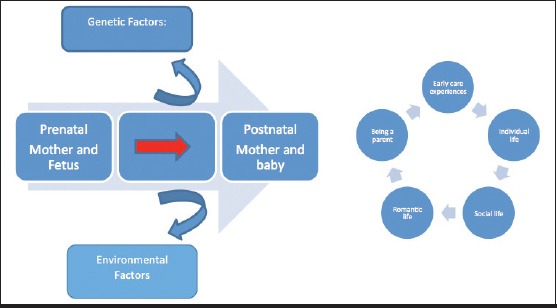

The factors that influence attachment start with the baby’s journey beginning with the formation of the fetus inside the mother’s abdomen and also involve the postnatal period. It has been demonstrated that the baby’s cognitive and socio-emotional development in later life is shaped with prenatal and postnatal influences. In addition, it has also been observed that the attachment type also influences the baby’s social, familial, and romantic relations in later life and their early care experiences with their own baby when they become a parent themselves (3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Development of Attachment (3)

In studies conducted with humans, it has been proposed that attachment relations start in the prenatal period and it has been reported that the fetus reacts to the mother’s emotions with their perception, reaction, and capturing ability, especially in the 26th week (13, 14). Mother-baby attachment shapes the neural pathways related to the socio-emotional adjustment in the baby. The mother’s psychological tension, her difficulty in responding to the relevant metabolic changes and the physiologic states, which could influence the mother’s health, are effective in the mother’s socio-emotional adjustment and balance. As a result, the mother-baby relationship and the baby’s socio-emotional adjustment and balance are influenced. It is thought that the baby’s socio-emotional balance is maintained stable for a lifetime with this influence. Examples for genetic factors include mood and being endurable and non-responsive to the states that introduce psychological tension in the mother, and environmental factors include parental-derived interactions (15).

It is thought that cortical and subcortical adjustments are also effective in addition to the baby’s and mother’s reciprocal responses to each other in the process of the mother-baby relationship. In Mogi et al.’s animal experiments (16), it was shown that synaptic terminal maturation and ultrasonic sound waves might be effective in attachment. Studies have shown that the mother’s interaction with her baby and attachment experiences in the early period lead to physiologic and hormonal responses in adolescence and early childhood in adjustment of social interaction. Studies from Japan and Italy showed that cultural-based attachment might be related with genetics. It has been shown that oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism and serotonin transport gene polymorphism cause positive attitude in mothers against their babies (3, 17). In the study conducted by Menardo et al. (18) in which the relationship between caregivers and children and genetic structure were investigated, it was reported that environmental factors (e.g. socio-cultural level) were effective in attachment. It has been stated that brain response mechanisms, which are one of the factors used by the mother when adjusting her relationship with her child, are strongly influenced by socio-economic status (19). The attachment type in babies is influenced by the conditions that create psychological tension in the mother. Socio-economic status is one of the most important titles. Children who live in poverty display insecure attachment more commonly compared with those who have high economic level (20). It is thought that problems experienced by parents throughout their marriage also influence secure attachment. While consistent parental behavior increases secure attachment, conditions causing psychological tension decrease secure attachment (21).

Lerum et al. (22) examined the conditions that influenced mother-baby attachment during pregnancy and found that the presence of planned pregnancy, household income level, visualization of the baby on ultrasonogram and fetal movements were effective in attachment. It was shown that unpleasant pregnancy experiences including depression and vomiting in the prenatal period influenced attachment negatively (23, 24). It has been reported that motherhood behaviors and insufficient attachment interaction were related with anxiety and depression in the postnatal period (25, 26).

Cultural influence is also an important factor in attachment, and the social structure in which the mother and the baby live determines the attachment type. In a study conducted with the parents who lived in communes (Kibbutzim) in Israel, it was found that secure attachment decreased in children who were raised mutually due to the fact that the caregivers were different, though the parents saw their own children during the day. It was observed that only 37% of these children showed secure attachment when they entered a strange environment at the age of 11–14 months (27). In the study conducted by Onnis et al. (28), it was reported that native language was effective in the mother-baby interaction and language communication with genetic origin might be a mediator in attachment. The conditions effective in attachment formation are given in Table 1 (29).

Table 1.

Processes that are effective in formation of attachment (29)

| The child’s personality characteristics |

| • Processes in the prenatal and postnatal period |

| • Neurologic and hormonal functions |

| • Genetic transfer |

| • Sex |

| • Mood characteristics |

| • Motor and cognitive functions |

| Family system |

| • Adaption of the roles of motherhood and fatherhood |

| • The parents’ childhood histories, their attachment relations with their own parents, their development levels, educations, employments and moods |

| • The quality of the parents’ relationship with each other |

| • The parents’ health states |

| • The degree of the mother’s fulfillment of her responsibilities for her child (interest, love, education, health and financial resources) |

| • Support from family elders and society |

| • Relationship patterns in the family (mother-father, mother-child, father-child, mother-father-child) |

| Socio-cultural factors |

| • Cultural values |

| • Gender roles |

| • Ethnic origin |

| • Education |

| • Unemployment rate |

| • Neighborhood and other communication networks |

| • Efficient power sources (media, politics, religion and technology) |

| • Historical structure (social environment, piece-war and economy) |

Conditions that negatively influence attachment have been investigated in many studies. A condition that negatively influences the relationship between the parents and the child is excessive crying. It has been found that eye contact and smiling are delayed in babies who cry excessively in the first months and do not respond to lapping, and mothers reject these babies at the end of the third month (30). Ainsworth et al. (31) reported that babies cried more when mothers ignored the crying of their babies. It was observed that a vicious cycle emerged because the mothers who remained non-responsive to excessive crying or gave up pacifying thinking that they were unsuccessful appeared indifferent and the babies cried more as a response to this. However, it was found that mothers who immediately responded when their three-month old babies cried had secure attachment with their babies at the 12nd month (31). Abbasoğlu et al. (32) found that there was no correlation between mother-baby attachment and infantile colic. It was observed that depression could influence mothers, and problems could be experienced in parental motivation and in life adjustments that parents should make for their children’s health as a result of disruption in the mother’s response to increased crying of her baby due to this influence (33).

Another condition that could influence attachment is depression of infancy. This condition, which came to the forefront in one study, has been defined in two ways as a result of interruption of mother-baby interaction for short- or long-term; short-term maternal deprivation (anaclitic depression), and long-term maternal deprivation (psychic hospitalization) (34).

In one study, it was reported that consistent, continuous, and responsible parental behavior were required and babies could respond to this behavior (35). In this reciprocal relationship, one side should give and the other side should receive. Babies who prefer to play with toys and objects rather than establishing social relationship with their mothers show less secure attachment in later life.

Applications that influence attachment in the early postnatal period and could enhance mother-baby attachment include: (1) early skin contact, (2) kangaroo method, and (3) sharing a room in the postnatal period. Mothers should be observed from the first postnatal minutes and the appropriate attachment behavior should be encouraged.

The following behaviors support and improve attachment: pacifying, cuddling and patting the baby, calling the baby with their name or gender (my boy/my girl), talking with the baby, establishing eye-to-eye contact, nursing and using the appropriate nutrition method, if nursing is not possible (36). Skin contact leads to increased oxytocin secretion in the mother in addition to triggering sensory stimuli. With increased oxytocin, the mother calms down and her social sensitivity increases. This may improve parental attitudes and support attachment (37). It has been observed that physical and emotional relations were supported and communication was improved with mothers who used the kangaroo method when cuddling their babies (38). It important to share the same room in the postnatal period. In fact, each time the mother and baby separate, a psychological tension develops for both sides. The mother and baby should stay in the same room unless a medical necessity exists. With this approach, early contact can be provided, milk production increases, and the mother’s self-confidence for more efficient nursing may increase (39).

Attachment in infancy is important in the shaping of individuals’ social, romantic, and individual lives. In addition to these influences, health problems (e.g. risky adolescent behaviors) may also be observed in individuals’ lives when a secure attachment is not provided. Establishment of baby-mother attachment starts before pregnancy, but is influenced by a wide period including pregnancy, delivery, and the postnatal period. Many conditions including genetic factors influence secure attachment and healthcare professionals should be aware of the conditions that could influence secure attachment in these periods. It should be aimed to perform effective and multidisciplinary evaluations that are appropriate for the risk factors found and to act as required, and to give appropriate support, both to the mother and baby.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - N.M.K, F.Ş.D.; Design - N.M.K, F.Ş.D.; Supervision - F.Ş.D.; Data Collection and/or Processing - N.M.K.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - N.M.K, F.Ş.D.; Literature Review - N.M.K.; Writing the Article - N.M.K.; Critical Review - F.Ş.D.

Conflict of Interest: The authors did not report any conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure: The authors stated that they did not receive any financial support for this study.

Hakem Değerlendirmesi: Dış bağımsız.

Yazar Katkıları: Fikir - N.M.K, F.Ş.D.; Tasarım - N.M.K, F.Ş.D.; Denetleme - F.Ş.D.; Veri Toplanması ya/ya da İşlemesi - N.M.K.; Analiz ya/ya da Yorum - N.M.K, F.Ş.D.; Dizin Taraması - N.M.K.; Yazıyı Yazan - N.M.K.; Eleştirel İnceleme - F.Ş.D.

Çıkar Çatışması: Yazarlar çıkar çatışması bildirmemişlerdir.

Mali Destek: Yazarlar bu çalışma için mali destek almadıklarını beyan etmişlerdir.

References

- 1.Soysal AŞ, Bodur Ş, İşeri E, Şenol S. Attachment Process in Infancy: A Review. J Clin Psy. 2005;88 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yüksel N. Ruhsal ve fiziksel gelişim, ruhsal hastalıklar kitabı 1. Baskı. Ankara Hatipoğlu Yayınevi. 1995:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esposito G, Setoh P, Shinohara K, Bornstein MH. The development of attachment: Integrating genes, brain, behavior, and environment. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325:87–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Vol I Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowlby J. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books; 1982. Attachment. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozlowska K, Hanney L. The network perspective:an integration of attachment and family systems theories. Fam Process. 2002;41:285–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson RA. Attachment theory and research. In: Lewis M, editor. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins; 2002. pp. 164–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavlak O. YayınlanmışDoktora Tezi. İzmir: Ege Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü; 2004. Maternal Bağlanma Ölçeği'nin Türk Toplumuna Uyarlanması; pp. 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowlby J. New York: Basic Books; 1973. Attachemnt and Loss: Seperation, anxiety and anger. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page T. The Attachment Partnership as Conceptual Base for Exploring 93 the Impact of Child Maltreatment. Child and Adolescent Social Work. 1999;16:419–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Main M, Solomon J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworht Strange Situation. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Atachment in the preschool year: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 121–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yılmaz SD. Prenatal Maternal - Fetal Attachment. HEAD. 2013;10:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloom KC. The development of attachment behaviors in pregnant adolecents. Nurs Res. 1995;44:284–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, Grebb JA. Baltimore, MD, US: Williams &Wilkins Co; 1994. Kaplan and Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry; pp. 161–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esposito G, Truzzi A, Setoh P, Putnick DL, Shinohara K, Bornstein MH. Genetic predispositions and parental bonding interact to shape adults'physiologicalresponses to social distress. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325:156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mogi K, Takakuda A, Tsukamoto C, et al. Mutual mother-infant recognition in mice: The role of pup ultrasonic vocalizations. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325:138–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senese VP, Shinohara K, Esposito G, Doi H, Venuti P, Bornstein MH. Implicit association to infant faces: Genetics, early care experiences, and cultural factorsinfluence caregiving propensities. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325:163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menardo E, Balboni G, Cubelli R. Environmental factors and teenagers'personalities: The role of personal and familialSocio-Cultural Level. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325:181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim MH, Shimomaeda L, Giuliano RJ, Skowron EA. Intergenerational associations in executive function between mothers and children in the context of risk. J Exp Child Psychol. 2017;164:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerezo MA, Pons-Salvador G, Trenado RM. Mother-infant interaction and children's socio-emotional development with high- and low-risk mothers. Infant Behav Dev. 2008;31:578–89. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belsky J, Rovine MJ. Nonmaternal care in the first year of life and the security of infant-parent attachment. Child Dev. 1988;59:157–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lerum CW, LoBiondo-Wood G. The relationship of maternal age, quickening, and physical symptoms of pregnancy to the development of maternal-fetal attachment. Birth. 1989;16:13–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1989.tb00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindgren K. Relationships among maternal-fetal attachment, prenatal depression, and health practices in pregnancy. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24:203–17. doi: 10.1002/nur.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumley JM. Attitudes to the fetus among primigravidae. Aust Paediatr J. 1982;18:106–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1982.tb02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaffney KF. Maternal-fetal attachment in relation to self-concept and anxiety. Matern Child Nurs J. 1986;15:91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindgren K. A comparison of pregnancy health practices of women in inner-city and small urban communities. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32:313–21. doi: 10.1177/0884217503253442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sagi A, van IJzendoorn MH, Aviezer O, Donnell F, Mayseless O. Sleeping out of home in a Kibbutz communal arrangement:it makes a difference for infant-mother attachment. Child Dev. 1994;65:992–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onnis L. Caregiver communication to the child as moderator and mediator of genes for language. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biller HB. London: Auburn House; 1993. Fathers and families paternal factors in child development. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson JP, Moss HA. Patterns and determinants of maternal attachment. J Pediatr. 1970;77:976–85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(70)80080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salter Ainsworth MD, Blehar MC, Waters E, Walls S. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1978. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbasoğlu A, Atay G, İpekçi AM, et al. The relationship between maternal-infant bonding and infantile colic. Çocuk Sağlığıve HastalıklarıDergisi. 2015;58:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho SS, Swain JE. Depression alters maternal extended amygdala response and functional connectivityduring distress signals in attachment relationship. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325:290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Öztürk MO. Ankara: Nobel Tıp Kitapevleri; 2002. Ruh sağlığıve bozukluklan; pp. 566–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis M, Feiring C, McGuffog C, Jaskir J. Predicting psychopathology in six-year-olds from early social relations. Child Dev. 1984;55:123–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anneanne-anne-bebek bağlanmasının incelenmesi. Yüksek Lisans Tezi. İzmir: Ege Üniversitesi Kadın Sağlığıve HastalıklarıHemşireliği Anabilim Dalı; 2007. Şen S; pp. 14–43. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD003519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Şener S, Karacan E. Anne-bebek-çocuk etkileşiminde olumlu ve olumsuz özellikler. İçinde. In: Ekşi A, editor. Ben Hasta Değilim - Çocuk Sağlığıve Hastalıklarının Psikososyal yönü. Ankara: Nobel Tıp Kitapevi; 1999. pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaafar SH, Lee KS, Ho JJ. Separate care for new mother and infant versus rooming-in for increasing the duration of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD006641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006641.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]