Abstract

Context

Although thyroid hormone replacement may improve outcomes in pregnant women with subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH), the extent to which they receive treatment is unknown.

Objective

To describe levothyroxine (LT4) treatment practices for pregnant women with SCH.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Large US administrative claims database.

Participants

Pregnant women with SCH defined by untreated TSH 2.5 to 10 mIU/L.

Main Outcome Measure

Initiation of LT4 as a function of treating clinician specialty (endocrinology, obstetrics/gynecology, primary care, or other), baseline TSH, patient clinical and demographic factors, and US region.

Results

We identified 7990 pregnant women with SCH; only 1214 (15.2%) received LT4. Treatment was more likely in patients with higher TSH, obesity, recurrent pregnancy loss, thyroid disease, and cared for by endocrinologists. Proportion of treated women increased over time; LT4 treatment was twice as likely in 2014 as in 2010. Women in Northeast and West US were more likely to receive LT4 compared with other regions. Asian women were more likely, whereas Hispanic women were less likely, to receive LT4 compared with white women. Endocrinologists started LT4 at lower TSH thresholds than other specialties, and treated women who were more likely to have had recurrent pregnancy loss and thyroid disease than women treated by other clinicians.

Conclusions

We found large variation in the prescription of LT4 to pregnant women with SCH, although most treatment-eligible women remained untreated. Therapy initiation is associated with geographic, clinician, and patient characteristics. This evidence can inform quality improvement efforts to optimize care for pregnant women with SCH.

In a national US cohort of 7990 pregnant women with SCH, only 15% of women received levothyroxine therapy, with marked variation in treatment initiation by clinician specialty.

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH), defined by an elevated TSH concentration with concurrently normal thyroid hormone levels, affects up to 15% of pregnancies in the US (1) and 17% in Europe (2). A recent meta-analysis showed that prevalence estimates for SCH in pregnancy range from 1.5% to 42.9%, depending on the diagnostic criteria, with a pooled prevalence estimate of 3.47% when using the 97.5th percentile as an upper limit for TSH (3). SCH in pregnancy is associated with multiple adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes (4) and indicators of intellectual disability in the offspring (5). As a result, despite inconsistent evidence supporting the effectiveness of thyroid hormone replacement in improving these outcomes in pregnant women with SCH and their offspring (6–10), clinical practice guidelines by the Endocrine Society (2012) (11), the European Thyroid Association (2014) (2), and the American Thyroid Association (2017) (12), all suggest levothyroxine (LT4) therapy in this context. In contrast, the 2015 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guideline did not advocate for treatment of SCH, citing lack of evidence that identification and treatment of SCH during pregnancy improves outcomes (13).

Recent reports from the US and China (6, 14, 15) have demonstrated that only a small subset of pregnant women with SCH receive thyroid hormone supplementation despite meeting the concurrent criteria for treatment of SCH. A variety of factors likely contributed to the observed lack of guideline-recommended initiation of thyroid hormone replacement. These include lack of awareness of evolving guidelines, particularly among the nonspecialists, established treatment practices, confusion in the face of inconsistent scientific evidence and professional society guidance, and patients’ decline of therapy. As the first step in the examination and remedy of these potential contributors, we assessed the degree to which LT4 initiation practices vary by clinician specialty among commercially insured pregnant women across the US between 2010 and 2014. We also examined the potential influence of other factors, including the patient’s baseline TSH level, demographic and clinical characteristics, and US region on the likelihood of LT4 initiation in this large and diverse population of pregnant women across the US.

Materials and Methods

Dataset

We performed a retrospective analysis of claims data from the OptumLabs® Data Warehouse, which includes de-identified claims data for privately insured and Medicare Advantage enrollees in a large, private US health plan. The database contains longitudinal health information on enrollees, representing a diverse mixture of ages, ethnicities, and geographical regions across the US. The health plan provides comprehensive full insurance coverage for physician, hospital, and prescription drug services (16, 17). Laboratory data are available for a subset of individuals based on data sharing agreements. Because this study involved analysis of preexisting, de-identified data, it was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Study population

Between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2014, we identified all women aged 18 to 55 years who had SCH defined by a TSH level 2.5 to 10 mIU/L (consistent with the concurrent definition of SCH during the study period). To capture women who had their laboratory testing done prior to seeing the clinician, we included TSH testing performed within 4 weeks before and up to 3 months after a medical claim indicating a pregnancy-related visit (6). Included individuals were required to have uninterrupted medical and pharmacy enrollment for 12 months before (to ascertain comorbidities and prior thyroid hormone use) and at least 42 weeks after (to ascertain pregnancy outcomes) the date of TSH measurement.

Women who had thyroxine concentrations checked within a week of the TSH test and these were found to be low (free thyroxine <0.8 ng/dL and/or total thyroxine <7.5 μg/dL), were excluded because this indicates overt hypothyroidism rather than SCH. We also excluded women with multiple gestation pregnancies, women who used medications affecting thyroid function (amiodarone, methimazole, and propylthiouracil), were treated with thyroid hormone during the 12-month baseline period, had no codes indicating end of pregnancy within 42 weeks of the index TSH date, or had a code indicating end of pregnancy (6) before the index TSH date (e.g., the TSH test was performed after the end of pregnancy).

Independent variables

We recorded baseline patient characteristics at the time of the index TSH test including age, race/ethnicity, annual household income in US dollars, and US geographic region. Age and sex were obtained directly from enrolment data. Race/ethnicity was classified as non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic black (black), Asian, or Hispanic based on self-report or derived rule sets, as reported previously (18). We collected information regarding personal history of thyroid disease including: nontoxic uninodular/multinodular goiter, goiter, Hashimoto disease, and thyroiditis (6). We also collected information regarding obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and recurrent pregnancy loss using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes (6).

Physician office visits in obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN), endocrinology, primary care (includes family medicine and internal medicine), and other specialties during the observation period were recorded. For all patients, we identified the specialties of clinicians seen closest to and within 30 days of the index TSH date, reflecting the clinician who likely screened for and diagnosed SCH. For the subset of patients who received LT4 therapy, we identified the specialties of clinicians seen closest before the LT4 prescription and within 30 days of index TSH test; this information is presented in Table 1 and Figure 1. For the comparator untreated group, we sought to identify a clinician most likely to decide on start of LT4 therapy in a pregnant patient. To do this, we applied a specialty hierarchy to all clinicians seen by the patient within 30 days of the index TSH date (this period was chosen to maximize the probability that the treatment decision is made in response to the TSH, rather than a later event), assigning highest priority to endocrinologists followed by OB/GYN, then primary care, then other. Finally, we identified specialties of clinicians who issued the first LT4 prescription; this information is presented in Table 2. Patients seen by clinicians of an unspecified/missing specialty and patients who did not have an office visit with a physician during the specified time frame were also included in the “other” category.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Treated vs Not Treated With LT4

| LT4 Treatment | ||||

| Characteristics | Yes (n = 1214) | No (n = 6776) | Total (N = 7990) | P |

| Age, y | 0.09 | |||

| Mean, SD | 31.9 (4.7) | 31.5 (5.1) | 31.6 (5.1) | |

| TSH concentration, mIU/L | 0.001 | |||

| Mean, SD | 4.7 (1.6) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.1) | |

| TSH concentration group, mIU/L | <0.001 | |||

| 2.5 –4.0 | 473 (39.0%) | 5734 (84.6%) | 6207 (77.7%) | |

| 4.1 –10.0 | 741 (61.0%) | 1042 (15.4%) | 1783 (22.3%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.001 | |||

| White | 679 (55.9%) | 4095 (60.4%) | 4774 (59.7%) | |

| Black | 74 (6.1%) | 469 (6.9%) | 543 (6.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 137 (11.3%) | 1104 (16.3%) | 1241 (15.5%) | |

| Asian | 289 (23.8%) | 938 (13.8%) | 1227 (15.4%) | |

| Unknown | 35 (2.9%) | 170 (2.5%) | 205 (2.6%) | |

| Annual household income, US$ | 0.02 | |||

| <$40,000 | 132 (10.9%) | 769 (11.3%) | 901 (11.3%) | |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 56 (4.6%) | 441 (6.5%) | 497 (6.2%) | |

| $50,000–$59,999 | 91 (7.5%) | 437 (6.4%) | 528 (6.6%) | |

| $60,000–$74,999 | 131 (10.8%) | 785 (11.6%) | 916 (11.5%) | |

| $75,000–$69,999 | 205 (16.9%) | 1147 (16.9%) | 1352 (16.9%) | |

| ≥$100,000 | 461 (38.0%) | 2631 (38.8%) | 3092 (38.7%) | |

| Unknown | 138 (11.4%) | 566 (8.4%) | 704 (8.8%) | |

| Patient residency region in US | 0.001 | |||

| Midwest | 97 (8.0%) | 657 (9.7%) | 754 (9.4%) | |

| Northeast | 259 (21.3%) | 931 (13.7%) | 1190 (14.9%) | |

| South | 561 (46.2%) | 3811 (56.2%) | 4372 (54.7%) | |

| West | 297 (24.5%) | 1377 (20.3%) | 1674 (21.0%) | |

| Y of TSH testing | 0.001 | |||

| 2010 | 198 (16.3%) | 1428 (21.1%) | 1626 (20.4%) | |

| 2011 | 231 (19.0%) | 1374 (20.3%) | 1605 (20.1%) | |

| 2012 | 227 (18.7%) | 1293 (19.1%) | 1520 (19.0%) | |

| 2013 | 276 (22.7%) | 1449 (21.4%) | 1725 (21.6%) | |

| 2014 | 282 (23.2%) | 1232 (18.2%) | 1514 (18.9%) | |

| Treating clinician specialty | 0.001 | |||

| OB/GYN | 557 (45.9%)a | 4021 (59.3%)b | 4578 (57.3%) | |

| Endocrinologist | 246 (20.3%)a | 402 (5.9%)b | 648 (8.1%) | |

| Primary care | 120 (9.9%)a | 437 (6.4%)b | 557 (7.0%) | |

| Other | 291 (24.0%)a | 1916 (28.3%)b | 2207 (27.6%) | |

| Key comorbidities | ||||

| Obesity | 74 (6.1%) | 339 (5.0%) | 413 (5.2%) | 0.23 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29 (2.4%) | 179 (2.6%) | 208 (2.6%) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension | 35 (2.9%) | 323 (4.8%) | 358 (4.5%) | 0.02 |

| Recurrent pregnancy loss | 31 (2.6%) | 98 (1.4%) | 129 (1.6%) | 0.02 |

| History of thyroid disease | 86 (7.1%) | 226 (3.3%) | 312 (3.9%) | 0.001 |

Clinician with office visit closest to the date of LT4 prescription.

Clinician specialty identified from all office visits within 30 days of the index TSH date based on the following hierarchy: endocrinology, obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN), primary care, and other.

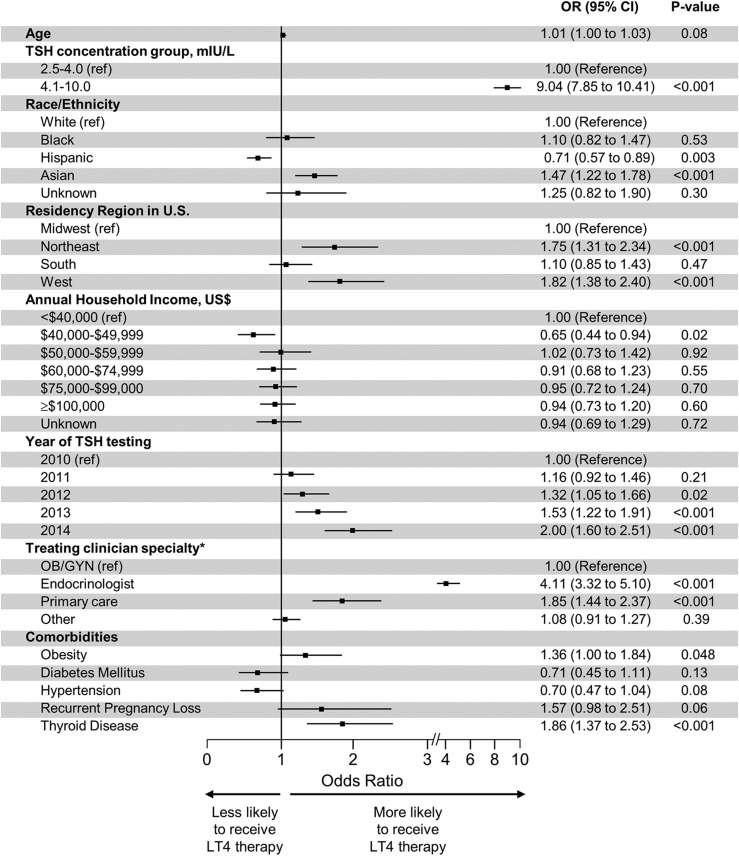

Figure 1.

Predictors of thyroid hormone initiation among pregnant women with subclinical hypothyroidism. For patients with LT4 prescription, provider specialty was based on the specialty of the provider with an office visit closest before the LT4 prescription and within 30 d of index TSH test. For patients without LT4 prescription, provider specialty was identified from among all office visits within 30 d of the index TSH date based on the following hierarchy: endocrinology, obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN), primary care, and other.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Treated Pregnant Women With SCH by LT4 Prescriber Specialty

| LT4 Presciber Specialty | ||||||

| Characteristics | OB/GYN (n = 644) | Endocrinologist (n = 332) | Primary Care (n = 115) | Other (n = 123) | Total (N = 1214) | P |

| Age, y | 0.05 | |||||

| Mean, SD | 31.7 (4.7) | 32.6 (4.7) | 31.4 (4.5) | 31.8 (4.5) | 31.9 (4.7) | |

| TSH concentration, mIU/L | 0.001 | |||||

| Mean, SD | 4.8 (1.5) | 4.4 (1.6) | 5.2 (1.8) | 5.0 (1.8) | 4.7 (1.6) | |

| TSH concentration group, mIU/L | 0.001 | |||||

| 2. –4.0 | 229 (35.6%) | 164 (49.4%) | 34 (29.6%) | 46 (37.4%) | 473 (39.0%) | |

| 4.1–10.0 | 415 (64.4%) | 168 (50.6%) | 81 (70.4%) | 77 (62.6%) | 741 (61.0%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.44 | |||||

| White | 353 (54.8%) | 184 (55.4%) | 66 (57.4%) | 76 (61.8%) | 679 (55.9%) | |

| Black | 32 (5.0%) | 24 (7.2%) | a | a | 74 (6.1%) | |

| Hispanic | 81 (12.6%) | 35 (10.5%) | a | a | 137 (11.3%) | |

| Asian | 164 (25.5%) | 76 (22.9%) | 32 (27.8%) | 17 (13.8%) | 289 (23.8%) | |

| Unknown | 14 (2.2%) | 13 (3.9%) | a | a | 35 (2.9%) | |

| Annual household income, US$ | 0.18 | |||||

| <$40,000 | 68 (10.6%) | 26 (7.8%) | 21 (18.3%) | 17 (13.8%) | 132 (10.9%) | |

| $40,000– $49,999 | 30 (4.7%) | 13 (3.9%) | a | a | 56 (4.6%) | |

| $50,000– $59,999 | 50 (7.8%) | 25 (7.5%) | a | a | 91 (7.5%) | |

| $60,000– $74,999 | 70 (10.9%) | 37 (11.1%) | 13 (11.3%) | 11 (8.9%) | 131 (10.8%) | |

| $75,0000– $69,999 | 98 (15.2%) | 66 (19.9%) | 14 (12.2%) | 27 (22.0%) | 205 (16.9%) | |

| ≥$100,000 | 252 (39.1%) | 129 (38.9%) | 36 (31.3%) | 44 (35.8%) | 461 (38.0%) | |

| Unknown | 76 (11.8%) | 36 (10.8%) | a | a | 138 (11.4%) | |

| Residency region in US | 0.001 | |||||

| Midwest | 43 (6.7%) | 26 (7.8%) | 16 (13.9%) | 12 (9.8%) | 97 (8.0%) | |

| Northeast | 101 (15.7%) | 114 (34.3%) | 26 (22.6%) | 18 (14.6%) | 259 (21.3%) | |

| South | 317 (49.2%) | 145 (43.7%) | 44 (38.3%) | 55 (44.7%) | 561 (46.2%) | |

| West | 183 (28.4%) | 47 (14.2%) | 29 (25.2%) | 38 (30.9%) | 297 (24.5%) | |

| Key comorbidities | ||||||

| Obesity | 38 (5.9%) | 17 (5.1%) | a | a | 74 (6.1%) | 0.66 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (1.7%) | a | a | a | 29 (2.4%) | 0.44 |

| Hypertension | 17 (2.6%) | a | a | a | 35 (2.9%) | 0.76 |

| Recurrent pregnancy loss | 11 (1.7%) | 19 (5.7%) | a | a | 31 (2.6%) | 0.002 |

| History of thyroid disease | 22 (3.4%) | 45 (13.6%) | a | a | 86 (7.1%) | 0.001 |

Cannot include N when cell size is less than 11 to protect patient confidentiality.

Primary outcome

Initiation of LT4 therapy, ascertained from pharmacy claims.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive summary analysis of patients’ baseline characteristics was performed. Data are presented as frequencies (percentages) for the categorical variables and means (SD) for the continuous variables. Differences between categorical variables were assessed using the χ2 test and between continuous variables using t test. We examined the pretreatment TSH concentration both as a continuous and a categorical variable (2.5 to 4.0 mIU/L vs 4.1 to 10.0 mIU/L). We chose a cutoff of 4.0 mIU/L for the analysis because this TSH concentration is used as a treatment threshold in the most recent American Thyroid Association guidelines for SCH during pregnancy (12). We performed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify the covariates associated with LT4 prescription. We also assessed for an interaction between clinician specialty and pretreatment TSH category adjusting for patient comorbidities. Results are reported as OR and 95% CI. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant and all testing was 2-sided. Because of the multiple statistical tests performed, a Holm-Bonferroni method was applied to all univariate comparisons. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

Study population

We identified 7990 pregnant women with SCH between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2014, of whom 1214 (15.2%) started LT4 treatment. The proportion of women who received LT4 therapy increased each year of the study: 12% (198/1626) were treated in 2010, 14% (231/1605) in 2011, 15% (227/1520) in 2012, 16% (276/1725) in 2013, and 19% (282/1514) in 2014; P = 0.001 (Table 1). Table 1 shows patients’ baseline characteristics. On average, women were 31.6 years old (SD 5.1). Treated patients had a higher pretreatment TSH concentration (mean 4.7 mIU/L, SD 1.6) and more often had pre-existing thyroid disease (7.1%) compared with untreated patients [3.3 mIU/L (SD 0.9) and 3.3%, respectively]; P = 0.001 for both. Only 42% (741/1783) of women who had a pretreatment TSH of 4.1 to 10 mIU/L began LT4. Treated women had a greater prevalence of past recurrent pregnancy loss (2.6%) but lower prevalence of hypertension (2.9%) compared with untreated patients (1.4% and 4.8%, respectively) (P = 0.02). There were similar rates of obesity and diabetes between the two groups.

The specialty of treating clinicians had an impact on the likelihood of LT4 initiation. Overall, 3989 (49.9%) women saw an OB/GYN closest to the time of their TSH testing, 1057 (13.2%) saw a primary care physician, 461 (5.8%) saw an endocrinologist, and 2483 (31.1%) saw a different clinician. Some women who did not see an endocrinologist immediately proximal to their TSH test still had a subsequent visit with an endocrinologist during the 30-day time period: 3.6% (145/3989) of women initially seen by OB/GYN, 5.8% (61/1057) of women initially seen by primary care, and 1.4% (36/2483) of women with other specialty visits. LT4 therapy was initiated in 37.7% of women who initially saw endocrinology, 14.1% of women who initially saw OB/GYN, 16.2% of women initially seen by primary care, and 12.4% of those with only other specialty visits. Irrespective of the first specialty seen, a higher proportion of treated women also had an endocrinology evaluation: 14.8% vs 1.8% of women who initially saw OB/GYN; 12.3% vs 4.5% of those who initially saw primary care; and 4.6% vs 1.0% of those with other specialty visits.

Predictors of LT4 treatment initiation

In a multivariate analysis (Fig. 1), the strongest predictors of LT4 initiation were TSH 4.1 to 10 mIU/L (OR 9.04, 95% CI 7.85 to 10.41, vs 2.5 to 4.0 mIU/L) and being seen by an endocrinologist (OR 4.11, 95% CI 3.32 to 5.10, vs OB/GYN). Women seen by a primary care physician (OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.44 to 2.37, vs OB/GYN) and with history of thyroid disease (OR 1.86; 95% CI 1.37 to 2.53) were also more likely to start LT4 therapy. There was no interaction between pretreatment TSH level and being seen by an endocrinologist (P = 0.12). There were also differences in LT4 prescription as a function of race/ethnicity, with Hispanic women nearly 30% less likely (OR 0.71, 95%CI 0.57 to 0.89), and Asian women 47% more likely (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.78), to start on LT4 therapy compared with white women. Finally, women living in the Northeast and West were more likely to receive LT4 therapy than patients living in the Midwest (and South).

Characteristics of treated women by LT4 prescriber specialty

Endocrinologists were more likely to initiate LT4 therapy in pregnant women with SCH and did so at much lower TSH thresholds than other specialists [mean TSH 4.4 mIU/L (SD 1.8) vs 4.8 mIU/L (SD 1.5) for OB/GYN and 5.2 mIU/L (SD 1.8) for primary care physicians]. However, women who saw an endocrinologist were more likely to have underlying thyroid disease and history of recurrent pregnancy loss (Table 2). Receiving endocrinology care was more likely in the Northeast US, whereas women in the South were more likely to be cared for by OB/GYN and women in the Midwest and West US were more likely to see primary care clinicians (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Principal findings

In this large US nationwide cohort, only one of every six pregnant women with SCH received LT4 treatment. Although the rates of LT4 initiation increased over time, from 12% in 2010 to almost 19% in 2014, opportunity for improvement remains, particularly in light of the marked variation in SCH treatment practices across clinician specialties and US regions. Whereas endocrinologists were more likely to initiate LT4 therapy than their primary care and OB/GYN colleagues, only 3.6% and 5.8% of pregnant women with SCH who initially saw OB/GYN and primary care, respectively, subsequently saw an endocrinologist. Finally, while the probability of LT4 initiation was influenced by pertinent clinical factors, such as TSH concentration levels, obesity, and history of thyroid disease, it was also impacted by nonclinical factors that suggest ongoing disparities in health care access and quality, particularly patient race/ethnicity, income, and region of residency in the US.

Policy implications

Maternal SCH is associated with worse maternal and neonatal outcomes (4), and observational studies found that LT4 treatment is associated with decreased risk of adverse events (6, 7, 8, 14). Whereas these findings were not supported by two multicenter randomized controlled trials from Europe (9) and the US (10), both of these trials were criticized for late initiation of LT4 therapy, which may have been too late to affect the offspring’s neurodevelopment and maternal pregnancy outcomes. As a result, the appropriate treatment of SCH is still unknown and there is no definitive consensus among professional societies.

In 2011, the American Thyroid Association recommended to treat pregnant women with SCH, defined as a TSH above 2.5 mIU/L with normal thyroxine levels, but only if women have positive thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO) (19). In 2012, the Endocrine Society published their recommendation of treating all pregnant women with SCH (11). The publication of these guidelines may have contributed to the increasing percentage of women treated each year from 2010 to 2014. In 2017, the American Thyroid Association released their updated guideline in which LT4 treatment is recommended for women positive for TPO if TSH is above 4.0 mIU/L and may be considered for TPO-positive women if TSH is above 2.5 mIU/L or for TPO-negative women if TSH is 4.0 to 10.0 mIU/L (12). Our study further illustrates the variation in patient evaluation and management strategies throughout the US. In the face of such uncertainty, additional data regarding current treatment practices can help inform clinical decision making and practice improvement strategies.

Importance of clinician specialty

Endocrinology involvement in the management of pregnant women with SCH was associated with much higher likelihood of LT4 prescription, whether the endocrinologists saw the patient immediately after diagnosis or shortly thereafter. Yet, only a small proportion of women with SCH saw an endocrinologist upon diagnosis. This reinforces concerns regarding inadequate access to endocrinology care in the US in general (20). Women treated by endocrinologists had greater prevalence of history of recurrent pregnancy loss and underlying thyroid disease. This is appropriate, yet even women without these conditions may benefit from specialty evaluation and, ultimately, consideration of LT4 therapy. Endocrinologists were also more likely to prescribe LT4 for milder cases of SCH and especially more likely to treat women whose TSH level was 2.5 to 4.0 mIU/L, which was consistent with the Endocrine Society guideline recommendations at the time of the study.

The cause of variation in practice by specialty is likely multifactorial. Because women treated by endocrinologists had higher risk for perinatal complications than those without endocrinology involvement, this may reflect their treating physicians’ perception of risk, whereby women with a higher risk of pregnancy complications were more likely to be referred to an endocrinologist and be offered thyroid hormone. However, there is no evidence that otherwise lower risk women with SCH do not derive the same benefit or face the same risk of adverse outcomes stemming from SCH as women with other risk factors. Second, discrepancies in recommendations among medical societies undoubtedly drive treatment decisions. Whereas endocrinologists are more likely to be aware of and adhere to Endocrine Society and American Thyroid Association guidelines, OB/GYN and primary care may be more familiar with the American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecologists guidelines (13), which make no recommendation for treatment of SCH. Endocrinologists, by nature of their training and experience, may be more facile with hypothyroidism and SCH management. Finally, the paucity of strong scientific evidence to support guideline recommendations may discourage clinicians from implementing them, particularly when treating thyroid disease is not a common component of their overall practice.

Health disparities in the care for SCH

We found that the probability of thyroid hormone replacement initiation for SCH in pregnancy was strongly affected by nonclinical patient factors including race/ethnicity, income, and region of residency in the US, supporting ongoing disparities in health care access and quality. It has been well documented that wide racial and ethnic disparities exist in many areas of health care and health outcomes, including obstetrical care and outcomes (21, 22). Moreover, perinatal health outcomes provide one of the starkest examples of geographic variation in the US. The most recent state-level data for preterm birth highlight the higher rates seen at the South region of the US (23). Recognizing that health care plays an important role in health disparities, health care policy and quality improvement efforts should aim to broaden access and increase the quality of obstetrical care available to all women.

Strengths and limitations of study

The main limitations of this study stem from its retrospective observational design and reliance on administrative claims data. Although administrative data may be the most complete and reliable method of capturing treatment practices, we could not reliably assess the impact of clinical context and factors related to health plan enrollment, diagnostic testing, and patient choice on the decision to initiate LT4 therapy. Specifically, inadequate information about the exact timing of the TSH measurement, gestational age at LT4 therapy initiation, and TPO antibody positivity did not allow us to assess their potential impact on SCH management. Because we could only capture filled prescriptions, primary nonadherence—whereby patients were prescribed LT4 therapy but never filled the prescription—would be classified as untreated. Although we examined a wide range of variables with the potential to affect SCH management decisions, there may be important confounders that were not measured or examined in our analysis. Finally, our study cohort comprised commercially insured women, such that women who are uninsured or have public health care coverage (Medicaid, the Indian Health Services, or the Veterans Administration) were not included and may have different treatment profiles.

Nonetheless, this national study assesses factors associated with LT4 initiation among pregnant women with SCH and the patterns of LT4 use throughout the US. The large sample size allowed a stratified analysis by TSH level and assessment of multiple predictors for LT4 treatment, which are clinically meaningful and informative. Our sample is not restricted to academic centers, thus representing real world estimates in the US and implications of thyroid hormone use in pregnant women with SCH.

Conclusions

There is marked variation in treatment practices for SCH in pregnancy among endocrinologists, primary care physicians, OB/GYN, and other clinicians, especially with mildly elevated TSH concentrations. Patient race/ethnicity, income, and region of residency in the US strongly impacted the probability of LT4 initiation suggesting ongoing disparities in health access and quality, particularly as most treatment-eligible women remained untreated. Further research is necessary to better understand the variation in practice among clinicians from different specialties and the barriers to LT4 therapy initiation in patients with SCH.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Freddy Toloza Bonilla for his editorial assistance.

Financial Support: S.M. receives support by the Arkansas Biosciences Institute, the major research component of the Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Proceeds Act of 2000. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas. The contents do not represent the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. R.G.M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant number K23DK114497. This study was funded by the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. The funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. Study contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- LT4

levothyroxine

- OB/GYN

obstetrics/gynecology

- SCH

subclinical hypothyroidism

- TPO

thyroid peroxidase

References and Notes

- 1. Blatt AJ, Nakamoto JM, Kaufman HW. National status of testing for hypothyroidism during pregnancy and postpartum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(3):777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lazarus J, Brown RS, Daumerie C, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Negro R, Vaidya B. 2014 European thyroid association guidelines for the management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy and in children. Eur Thyroid J. 2014;3(2):76–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dong AC, Stagnaro-Green A. Differences in diagnostic criteria mask the true prevalence of thyroid disease in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2019;29(2):278–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maraka S, Ospina NM, O’Keeffe DT, Espinosa De Ycaza AE, Gionfriddo MR, Erwin PJ, Coddington CC III, Stan MN, Murad MH, Montori VM. Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2016;26(4):580–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson W, Russell G, Baragwanath G, Matthews J, Vaidya B, Thompson-Coon J. Maternal thyroid hormone insufficiency during pregnancy and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;88(4):575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maraka S, Mwangi R, McCoy RG, Yao X, Sangaralingham LR, Singh Ospina NM, O’Keeffe DT, De Ycaza AE, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Coddington CC III, Stan MN, Brito JP, Montori VM. Thyroid hormone treatment among pregnant women with subclinical hypothyroidism: US national assessment. BMJ. 2017;356:i6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nazarpour S, Ramezani Tehrani F, Simbar M, Tohidi M, Alavi Majd H, Azizi F. Effects of levothyroxine treatment on pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with autoimmune thyroid disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176(2):253–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nazarpour S, Ramezani Tehrani F, Simbar M, Tohidi M, Minooee S, Rahmati M, Azizi F. Effects of levothyroxine on pregnant women with subclinical hypothyroidism, negative for thyroid peroxidase antibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018; 103(3):926–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lazarus JH, Bestwick JP, Channon S, Paradice R, Maina A, Rees R, Chiusano E, John R, Guaraldo V, George LM, Perona M, Dall’Amico D, Parkes AB, Joomun M, Wald NJ. Antenatal thyroid screening and childhood cognitive function. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, Varner MW, Sorokin Y, Hirtz DG, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Thorp JM Jr, Saade G, Tita AT, Rouse DJ, Sibai B, Iams JD, Mercer BM, Tolosa J, Caritis SN, VanDorsten JP; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):815–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Groot L, Abalovich M, Alexander EK, Amino N, Barbour L, Cobin RH, Eastman CJ, Lazarus JH, Luton D, Mandel SJ, Mestman J, Rovet J, Sullivan S. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2543–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, Brown RS, Chen H, Dosiou C, Grobman WA, Laurberg P, Lazarus JH, Mandel SJ, Peeters RP, Sullivan S. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27(3):315–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 148: Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(4):996–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maraka S, Singh Ospina NM, O’Keeffe DT, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Espinosa De Ycaza AE, Wi CI, Juhn YJ, Coddington CC III, Montori VM, Stan MN. Effects of levothyroxine therapy on pregnancy outcomes in women with subclinical hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2016;26(7):980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang S, Teng WP, Li JX, Wang WW, Shan ZY. Effects of maternal subclinical hypothyroidism on obstetrical outcomes during early pregnancy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35(3):322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wallace PJ, Shah ND, Dennen T, Bleicher PA, Crown WH. Optum Labs: building a novel node in the learning health care system [published correction appears in Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1703]. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7): 1187–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. OptumLabs. OptumLabs and OptumLabs Data Warehouse (OLDW) Descriptions and Citation. Cambridge, MA: n.p., February 2018. PDF. Reproduced with permission from OptumLabs. 2018.

- 18. Hershman DL, Tsui J, Wright JD, Coromilas EJ, Tsai WY, Neugut AI. Household net worth, racial disparities, and hormonal therapy adherence among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(9):1053–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander E, Azizi F, Mestman J, Negro R, Nixon A, Pearce EN, Soldin OP, Sullivan S, Wiersinga W; American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2011;21(10):1081–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Endocrine Society. Endocrine clinical workforce: supply and demand projections. Available at: https://www.endocrine.org/-/media/endosociety/files/advocacy-and-outreach/other-documents/2014-06-white-paper--endocrinology-workforce.pdf?la=en. Accessed 24 August 2018.

- 21. Alexander GR, Wingate MS, Bader D, Kogan MD. The increasing racial disparity in infant mortality rates: composition and contributors to recent US trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):51.e1––9.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bryant AS, Washington S, Kuppermann M, Cheng YW, Caughey AB. Quality and equality in obstetric care: racial and ethnic differences in caesarean section delivery rates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(5):454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013. Dec 30;62(9):1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]