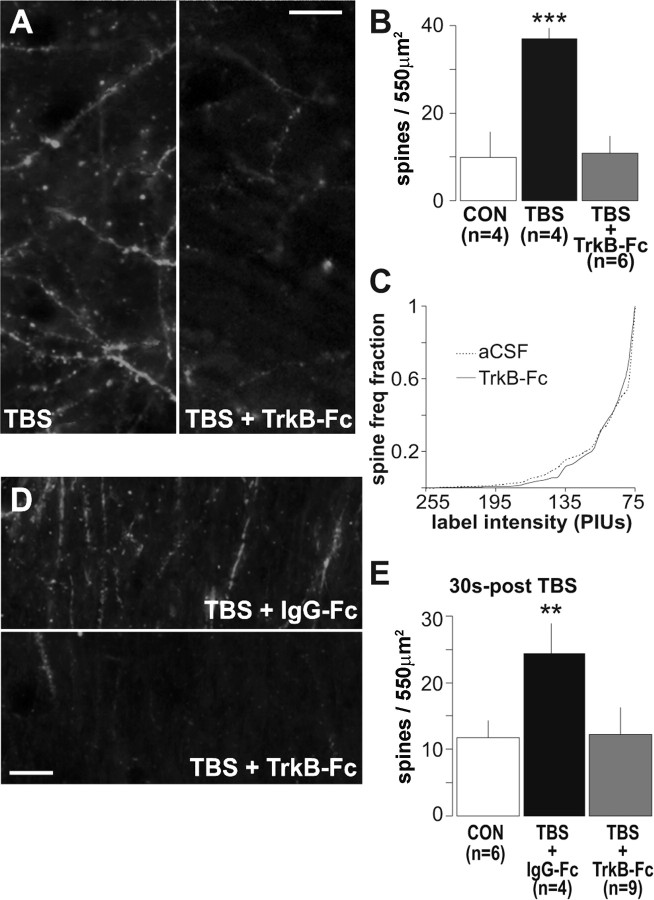

Figure 6.

Sequestering extracellular BDNF prevents TBS-induced actin polymerization. A, Representative photomicrographs of the CA1 sampling region shows a scattering of densely phalloidin-labeled spines in a slice given TBS alone and the absence of dense spine labeling in a slice given TBS in the presence of 1 μg/ml TrkB-Fc (TBS + TrkB-Fc; scale bar, 10 μm). B, A plot of group mean ± SEM spine counts confirms that TBS markedly increased numbers of intensely labeled spines relative to controls (CON; ***p = 0.001, two-tailed t test) and that this effect was blocked by TrkB–Fc (p > 0.8 vs controls). C, Cumulative fraction spine intensity plots (as in Fig. 3H) show similar intensity distributions for phalloidin-labeled spines for control slices maintained in aCSF (dashed line) and slices treated with 1 μg/ml TrkB–Fc alone (solid line; i.e., in the absence of TBS): no differences between TrkB–Fc and aCSF slices were detected (p > 0.8, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). D, Photomicrographs of rhodamine–phalloidin labeling in field CA1 in slices receiving the control Ig, IgG–Fc (TBS + IgG–Fc), or 2 μg/ml TrkB–Fc (TBS + TrkB–Fc) for 2 min starting 30 s after TBS. E, Quantification of densely labeled spines shows that post-TBS application of IgG–Fc did not block theta-induced increases in the number of intensely labeled spines (**p < 0.01 vs control, two-tailed t test), whereas post-TBS infusion of TrkB–Fc eliminated the effect.