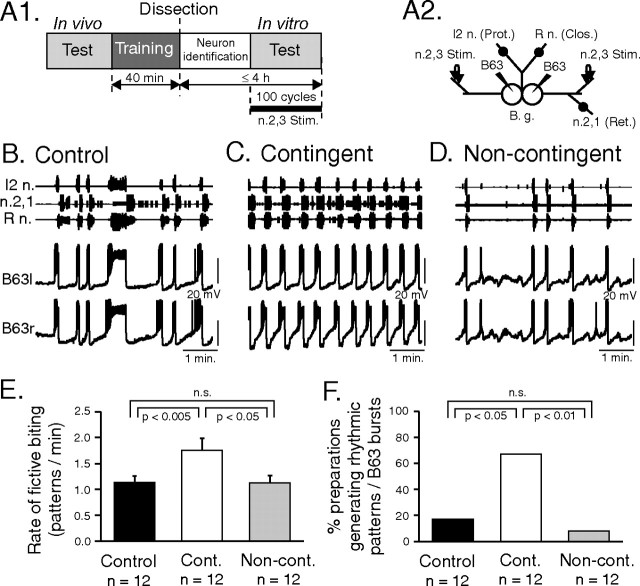

Figure 8.

Neuronal correlates of contingent-dependent behavioral changes. A1, Experimental protocol. After contingent, noncontingent, or control training (see also Fig. 4), the buccal ganglia of animals (n = 7) from each group were immediately isolated and the generation of radula motor output (fictive biting) was tested within 4 h of in vivo training. A2, Schematic of a bilateral buccal ganglia (B.g.) preparation from which extracellular recordings (indicated by black dots) were made from the I2n. (radula protractor motoneurons), n.2,1 (retractor motoneurons), and R n. (closure motoneurons). The B63 radula pattern-initiating neurons were also identified and recorded intrasomatically (arrowheads) in the two buccal ganglia. During in vitro testing, a continuous inciting stimulus was provided by monotonic electrical stimulation (2 Hz, 8.5 V) of the bilateral n.2,3 sensory nerves. B–D, Samples of simultaneous extracellular recordings of radula motor output from indicated motor nerves (I2n., n.2,1., R n.) and intracellular recordings from the left (l) and right (r) B63 pattern-generating neurons during the posttraining in vitro test period of different control (B), contingent (C), and noncontingent (D) preparations. E, F, Group comparisons. E, The rate of fictive biting (patterns per minute) generated in the in vitro test period remained higher in the contingent (Cont.) group than in either the control (q2 = 4.062) or noncontingent (Non-cont.; q3 = 3.315) groups. The control and noncontingent groups were not significantly different (q2 = 0.878). F, The proportion of isolated preparations that generated rhythmic fictive biting and associated B63 impulse bursts was significantly higher in preparations from the in vivo contingently trained group than either the control (p < 0.05) or noncontingently trained groups (p < 0.01). Control versus noncontingent groups, not significant (n.s.).