Abstract

Purpose.

To examine the longitudinal relationship between depression, delinquency, and trajectories of delinquency among Hispanic children and adolescents.

Methods.

Propensity score matching is used to match depressed and non-depressed youth and a combination of group-based trajectory and multinomial logistic regression techniques are used.

Results.

After adjusting for pre-existing differences between depressed and non-depressed youth, the causal relationship between depression and delinquency and the association between depression and trajectories of delinquency appears to be largely spurious. However, the effect of depression on predicting a high rate and increasing trajectory of delinquency is robust.

Conclusions.

Depression and high-rate offending are linked in a sample of Hispanic children and adolescents.

Keywords: developmental, life-course, mental health, delinquency, depression, Hispanics

Introduction

Although there has been some discussion that the prevalence of mental health disorders among youth has been increasing in recent years (Merikangas et al., 2010), whether that may be an actual increase in disorders and/or their diagnoses, a recent meta-analysis of 41 studies, representing 27 countries, and published between 1985 and 2012 indicated that the prevalence rates of mental health disorders among adolescents did not significantly vary as a function of geography or time, but rather as a function of several other factors including sample representativeness, sample frames, and diagnostic interview (Polanczyk et al., 2015). Nevertheless, lifetime and annual prevalence rates of mental health issues among youth have been shown to vary. For example, the lifetime prevalence of mental health disorders in adolescents between ages 13 and 18 has been reported to be as high as 46.3%, with as many as one in every five having a severe diagnosis (Merikangas et al., 2010). Comparatively, the Centers for Disease Control has estimated the 12-month prevalence of major depression among youth ages 8–15 at 2.7% and 13.1% for any disorder. In addition, Avenevoli et al. (2015) reported that the lifetime prevalence of depression, specifically, was as high as 11.0%, with females reporting higher levels of depression than males. Similar studies have found gender differences in depression as well (Cauffman, 2004; Merikangas et al., 2010; Roberts & Chen, 1995; Schraedley et al., 1999).

The research reported on above has undoubtedly been important for matters related to theory and policy. Yet, a major focus of the aforementioned research has been its heavy reliance on samples of Whites and African-Americans. Thus, and much like extant research in criminology and criminal justice more generally (Piquero, 2008a, 2015), there has been a critical lack of research that has investigated the rates of mental health issues among Hispanic children and adolescents. In this vein, few studies have compared more than two racial/ethnic minority groups (usually White/Caucasian and Black/African-American), and those that have generally report conflicting results (Caufman, 2004; McLaughlin et al., 2007). In contrast, Hispanic adolescents have demonstrated higher levels of depression than White adolescents (Merikangas et al., 2010; Roberts & Chen, 1995; Schraedley et al., 1999). As has been the case in in nationally representative samples of children and adolescents (Cauffman, 2004; Merikangas et al., 2010; Roberts & Chen, 1995; Schraedley et al., 1999), Hispanic females have also been observed to report higher levels depression (Roberts & Chen, 1995).

In a sample of Puerto Rican children and adolescents, Canino et al. (2004) reported last-year prevalence rates of any mental health diagnosis at 16.4% and a 3.0% prevalence rate of depression. These authors also found that girls had an increased odds of reporting major depression. Relying on data from Puerto Rico adolescents aged 11–17 who were selected from an island-wide probability household sample of children, Gonzalez-Tejera et al. (2005) reported that although there were no statistically significant differences in minor or major depression prevalence by gender according to parent reports, the youth reports revealed significantly higher rates of both minor and major depression among females. Comparatively, the effect of age on the prevalence of depression has generated mixed findings. For instance, Roberts and Chen (1995) found that age had no effect, but other studies have reported small increases in the rates of depression among older youth (Avenevoli et al., 2015; Canino et al., 2009; Merikangas et al., 2010; Schraedley et al., 1999).

McLaughlin et al. (2007) have speculated that higher rates of mental health issues among Hispanic youth may be related to conflicting gender expectations between Hispanic culture and norms and American culture and norms for those that live in the United States. And, these conflicting gender expectations are often more pronounced for Hispanic females. For example, traditionally Hispanic female children and adolescents are taught to be more passive, family-centric, and are expected to maintain family harmony even at the expense of their own well-being, whereas American culture promotes autonomy and individuation from the family (McLaughlin et al., 2007). For this reason, studies that examine the effects of depression on antisocial behaviors, such as juvenile delinquency among Hispanics, generally control for the effect that cultural stress and acculturation has on these behaviors (Jennings et al., 2010a). In addition, using data from Puerto Rican participants from the Boricua Youth Study (BYS; Bird et al., 2006a; 2006b), Olazagasti et al. (2013) found that youth internalizing symptoms (including depression) declined over time, and that youth in New York had higher levels of internalizing symptoms that youth in Puerto Rico. These differences in internalizing behavior across geographic context were largely attributed to differences in experiences of discrimination and exposure to violence. Higher levels of parental warmth have also been associated with a lower odds of depressive symptoms over time among BYS youth, and this relationship was reported to be stronger for youth in Puerto Rico relative to youth in New York (Santesteban-Echarri et al., 2017).

When considering the depression-delinquency nexus, it is possible that the effects of depression specifically may have been understated in previous research. For instance, Armsden et al. (1990) have indicated that juveniles with depression should be less visible to law enforcement, despite the possibility that these juveniles may in fact be simply apathetic to getting arrested (see also, Hirschfield et al., 2006). Armsden et al. also reported that children with symptoms of depression were more withdrawn and had less satisfying peer relationships. As such, Hirschfield et al. (2006) have suggested that this scenario likely results in a decrease in the effect that peer relationships have on delinquency.

Despite this important but small body of research, only recently have criminologists begun to examine the nature of the relationships between various risk factors, mental health, and delinquency among Hispanic youth relying on longitudinal data. For example, Jennings et al. (2010a) utilized data from the Boricua Youth Study (BYS; Bird et al., 2006a; 2006b), and discovered that while many traditional risk and protective factors were associated with delinquency, there was an independent and robust relationship between the youth having a parent who had attempted suicide and the youth’s delinquency. More importantly, this effect maintained its strength and significance over a three year period.

Coinciding with the increased attention toward the constellation of these risk and protective factors, mental health, and delinquency among Hispanics has also been an increase in the application of group-based offending trajectories among Hispanic samples. Briefly, group-based trajectory models are designed to isolate unique groups who may differ on the level, rate, and length of a particular characteristic, such as delinquency. In a recent and comprehensive review, Jennings and Reingle (2012) examined 105 studies of trajectories of aggression, delinquency, and violence and found that the number of trajectory groups has been found to range from two to seven, with the most prevalent being three to four groups. Furthermore, these groups largely conform to Moffitt’s (1993) description of adolescent-limited and life-course persistent offenders, but other groups such as escalators, desistors, and late-onset offenders have also been identified. Interestingly, similar results were detected when disaggregating Hispanic samples by gender (Jennings et al., 2010b; Reingle et al., 2011), when comparing multiple racial/ethnic groups including Hispanics (Reingle et al., 2012), and when utilizing different samples of Hispanic youth (Maldonado-Molina et al., 2009; 2010a). With regard to the risk and protective factors associated with group membership, Maldonado-Molina et al. (2009) and Jennings et al. (2010b), noted that Hispanic-specific risk factors such as cultural stress and acculturation often distinguished the trajectory groups as well as more traditional risk and protective factors such as exposure to violence, stressful life events, and self-esteem. In addition, recent research has reported that both stressful life events and self-esteem have been found to be related to depression (Michl et al., 2013; Orth & Robins, 2013), and depression has been found to be a significant risk factor for Hispanics whose offending trajectory started later and escalated from one wave to the next (Reingle, Jennings, & Maldonado-Molina, 2011).

The Current Study

The relationship between mental health and delinquency has been found to be complex (El Sayed et al., 2016), but there is an increasing need to understand these complexities using more robust analytical strategies and longitudinal data that can better permit causal inferences. More importantly, this type of research is noticeably rare with Hispanic population-based samples. With recognition of these issues, the current study relies on longitudinal data from the Boricua Youth Study (BYS; Bird et al., 2006a; 2006b) to assess the relationship between mental health, specifically depression, and delinquency. More importantly, this study assesses this linkage relying on propensity score matching methods and group-based trajectory analysis to better determine the causal nature of this relationship and to determine if this relationship has differential effects on different offender groups.

Methods

Data and Sample

The current study uses data from two samples from the Boricua Youth Study (BYS) to examine the relationship between depression and delinquency among Hispanic youth. The BYS is a longitudinal study that consists of three waves of child and parent-report data collected annually between 2000 and 2004 from a matched, probability-based sample of Puerto Rican families from Bronx, New York and San Juan, Puerto Rico. Interviews were conducted in the youth’s homes by trained interviewers, and different interviewers simultaneously surveyed the children and their parents in separate areas of the home. These questionnaires were administered using computer-assisted methods, and the participant could choose to complete the electronic survey in either Spanish or English. More information regarding the data collection procedures exist elsewhere (Bird et al., 2006a; 2006b).

The probability sampling process yielded 1,414 eligible participants from Bronx, New York, 1,138 of which were interviewed (completion rate of 80.5%). The sample from San Juan, Puerto Rico consisted of 1,353 of the 1,526 eligible participants (completion rate of 88.7%). Gender did not vary significantly across sites (t = 0.19, p = .85). In the two annual follow-ups (Waves 2 and 3), sample retention was approximately 85% and missing data was less than 4%. The gender distribution in both samples was roughly equivalent. In the Bronx, 51.36% of the sample were males, while 51.75% of the sample were males in San Juan. Importantly, the BYS sample was made up of two different age cohorts (ages 5–9 and ages 10–13) at both sites. This analysis relies on only the ages 10–13 cohorts from both sites as depression was not assessed for the younger cohorts at Wave 1.1 As such, the analytic sample size for the youth with complete data for the current study is n=1,059.

Dependent Variable

Delinquency was measured via a common self-report instrument that contained approximately 30 items (Elliott et al., 1985), and this same measure has been used in prior BYS delinquency-related research (Jennings et al., 2009, 2010, 2016; Maldonado-Molina et al., 2009, 2010b). Specifically, the youth were asked to report either “yes” or “no” to whether they participated in a number of delinquent acts in the prior year, and the number of “yes” responses were summed to create an overall variety index (Hindelang et al., 1981), which have the feature of being highly correlated with the frequency of offending but without the skewness problems associated with frequency measures (Monahan & Piquero, 2009). Example items include: “Carried a hidden weapon?”; “Drunk in a public place?”; “Purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you, for example smearing or pouring paint on something, writing graffiti on walls, or breaking, cutting, or marking up something?”; “Purposely set fire to a house, building, car or other property or tried to do so?”; “Stolen or tried to steal things worth less than $5?; Stolen or tried to steal something worth over $100?”; “Stolen or tried to steal a motor vehicle, such as a car or motorcycle?”; “Attacked someone with a weapon or to seriously hurt or kill them?”; “Been involved in a gang fight?”; “Sold drugs to anyone?”; “Been arrested or picked up by the police for anything other than a minor traffic offenses?”, etc. This same measure was available at Waves 1, 2, and 3, and all of these measurements are used in various stages of the analysis plan when relevant.

Independent Variables

The main independent variable of interest is mental health, specifically depression. This mental health issue was measured with the following item: “Was there a time in the last year when you felt sad or depressed for a long time each day?” This item was dichotomous, where 1= depressed youth and 0=non-depressed youth. Wave 1 depression was utilized in order to establish temporal order for one of the set of analyses that follow. Beyond this main independent variable of interest, a host of risk and protective factors (all measured at Wave 1) were incorporated as covariates that have all been used in previous BYS delinquency-related research (Jennings et al., 2009, 2010, 2016; Maldonado-Molina et al., 2009, 2010) including: site (Bronx= 1; San Juan= 0), gender (1= Male; 2=Female), age (continuous), attitudes toward delinquency (higher values indicative of more supportive attitudes toward delinquency) (Loeber et al., 1998), sensation-seeking (higher values indicative of greater sensation-seeking) (Russo et al., 1991, 1993), self-esteem (higher values indicative of more self-esteem) (Harter, 1982), peer relationships (higher values indicative of more positive relationships with peers) (Hudson, 1992), peer delinquency (higher values indicative of having more delinquent peers) (Loeber et al., 1998), parent-child interaction (higher values indicative of more positive parent-child interactions) (Loeber et al., 1998), exposure to violence (higher values indicative of greater exposure to violence) (Raia, 1995; Richters and Martinez, 1993), coercive discipline (higher values indicative of greater use of coercive disciplining practices by the parents) (Goodman et al., 1998), cultural stress (higher values indicative of more cultural stress) (Magafia et al., 1996; Mendoza, 1989), acculturation (higher values indicative of being more acculturated) (Magafia et al., 1996; Mendoza, 1989), school environment (higher values indicative of a more negative school environment), social support (higher values indicative of greater social support) (Thoits, 1995), locus of control (higher values are indicative of a greater external locus of control), stressful life events (higher values indicative of having experienced more stressful life events) (Goodman et al., 1998; Johnson & McKutcheon, 1980), and welfare status (1= family receiving welfare assistance; 0= family not receiving welfare assistance) (for additional details on all of these measures, see Bird et al., 2006a; 2006b; Maldonado-Molina et al., 2009).

Analytic Strategy

The analysis proceeds in a series of stages. In the first stage, propensity score matching (PSM) methods are applied in an effort to better rule out confounding factors in the mental health-delinquency relationship and also to increase the precision of the estimates (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983; Rosenbaum, 2002). PSM is becoming much more commonplace in criminology, and has been applied to a number of topics in the criminological literature as a robust method for addressing selection effects (Jennings et al., 2014a,b, 2015, 2017), and have been previously used in prior BYS research (Bird et al., 2006a; 2006b). Specifically, we apply PSM to simulate a quasi-experimental design where we are able to statistically identify a matched sample of treated cases (i.e., BYS youth who you are depressed at Wave 1) and control cases (BYS youth who are not depressed at Wave 1) who have been equated across a range of risk and protective factors. Resultant propensity scores are derived via a logit model relying on the following risk and protective factors including: site, gender, age, attitudes toward delinquency, sensation-seeking, self-esteem, peer-relationships, peer delinquency, parent-child interaction, exposure to violence, coercive discipline, cultural stress, acculturation, school environment, social support, locus of control, stressful life events, and baseline (Wave 1) delinquency. Following the PSM estimation, in stage two we conduct a host of statistical comparisons via t-tests between the depressed youth (“treatment cases”) and the non-depressed youth (“control cases”) across the range of risk and protective factors both prior to and post-matching, so as to examine (and ensure) that the PSM was able to render insignificant any potential differences between depressed and non-depressed youth. In the third stage, we assess the causal relationship between depression (measured and matched on at Wave 1) and delinquency (measured at Waves 2 and 3) by estimating t-tests on the frequency of delinquency for the depressed and non-depressed youth both prior to and post-matching. The propensity score matching procedure is estimated using a nearest-neighbor algorithm with a caliper of 0.20 (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983; Rosenbaum, 2002).

Stage four involves the estimation of group-based trajectories of delinquency. Like PSM, this analytic technique has become increasingly common and widely utilized in the criminological literature (Jennings and Reingle, 2012; Nagin, 2005, 2010; Piquero, 2008b). Specifically, we estimate trajectories of delinquency for the BYS youth via an iterative process varying the parametric form (constant, linear, quadratic, cubic) and the number of groups in an effort to maximize the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) in order to arrive at the most optimal model. Model precision is also assessed by examining the posterior probabilities of group assignment, where Nagin (2005, 2010) suggests that group-based probabilities greater than .70 are indicative of model precision. In addition, as the dependent variable represents a frequency/count of delinquency, we estimate the trajectory models using the zero-inflated (ZIP) functional form. Following the estimation of the trajectory models, we estimate a series of oneway analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Tukey’s b post-hoc tests to determine how the range of risk and protective factors may (or may not) distinguish the trajectory groups from one another. The final stage of the analysis focuses on the estimation of multinomial logistic regression models to assess: 1) whether (or not) the effect of depression (measured at Wave 1) has similar or differential effects on trajectories of delinquency (Waves 1–3), and 2) whether (or not) the effects of depression on trajectories of delinquency are observed after controlling for propensity scores derived from the range of risk and protective factors described above.2

Results

Table 1 presents the pre- and post-matching comparisons between the depressed youth and the non-depressed youth across the range of the risk and protective factors. As can be seen, prior to matching, the depressed youth significantly differed from the non-depressed youth on 14 of the 19 covariates. Specifically, a greater proportion of depressed youth were from the Bronx sample (t= −3.10, p< .05), a greater proportion of females reported being depressed (t= −3.82, p< .05), and depressed youth exhibited significantly more favorable attitudes toward delinquency (t= −2.08, p< .05), less self-esteem (t= 2.63, p< .05), less positive peer relationships (t= 2.43, p< .05), more delinquent peers (t= −1.99, p< .05), more exposure to violence (t= −6.31, p< .05), more parental use of coercive disciplining practices (t= −4.12, p< .05), more acculturation (t= −2.77, p< .05), a more negative school environment (t= −3.43, p< .05), more social support (t= −2.32, p< .05), more locus of control (t= −2.14, p< .05), more stressful life events (t= −4.92, p< .05), and more baseline (Wave 1) delinquency (t= −5.21, p< .05) compared to their non-depressed counterparts. In contrast, after applying PSM none of these statistically significant differences remained, which indicates that the PSM procedure was successful in eliminating all of these potential confounding influences that may have resulted in selection effects when trying to assess the causal linkage between depression and delinquency.

Table 1.

Bivariate Comparisons of Covariates Before and After Matching for Wave 1 Depression.

| Variables | Before Matching n=802 Non-Depressed Youth | n=257 Depressed Youth | t-test | After Matching n=249 Non-Depressed Youth | n=249 Depressed Youth | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site (Bronx=1) | 0.41 | 0.52 | −3.10*** | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| Gender | 1.45 | 1.58 | −3.82*** | 1.57 | 1.58 | −0.18 |

| Age | 11.79 | 11.83 | −0.47 | 11.76 | 11.82 | −0.67 |

| Attitudes toward delinquency | 2.50 | 3.05 | −2.08* | 2.92 | 2.95 | −0.08 |

| Sensation-seeking | 3.58 | 3.77 | −1.07 | 3.61 | 3.73 | −0.56 |

| Self-esteem | 12.63 | 12.08 | 2.63** | 11.97 | 12.13 | −0.56 |

| Peer relationships | 4.34 | 4.16 | 2.43** | 4.18 | 4.18 | 0.00 |

| Peer delinquency | 0.18 | 0.22 | −1.99* | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.46 |

| Parent-child interaction | 0.78 | 0.76 | 1.54 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.52 |

| Exposure to violence | 2.02 | 3.45 | −6.31*** | 3.12 | 3.29 | −0.50 |

| Coercive discipline | 0.24 | 0.36 | −4.12*** | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.30 |

| Cultural Stress | 0.13 | 0.15 | −1.30 | 0.14 | 0.15 | −0.54 |

| Acculturation | 2.57 | 2.74 | −2.77** | 2.79 | 2.73 | 0.84 |

| School environment | 2.96 | 3.64 | −3.43*** | 3.49 | 3.57 | −0.34 |

| Social support | 1.95 | 2.03 | −2.32* | 2.02 | 2.02 | 0.00 |

| Locus of control | 0.72 | 0.77 | −2.14* | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.44 |

| Stressful life events | 0.66 | 1.10 | −4.92*** | 0.93 | 1.05 | −0.99 |

| Welfare | 0.45 | 0.48 | −0.53 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| Baseline Delinquency (Wave 1) | 0.50 | 0.97 | −5.21*** | 1.41 | 1.53 | −0.64 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

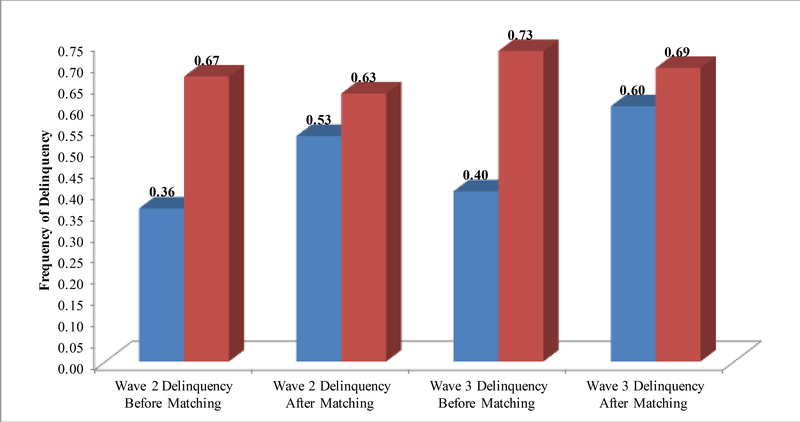

Figure 1 illustrates the causal relationship between depression and delinquency. The results demonstrate that depressed youth commit delinquency with a greater frequency compared to non-depressed youth prior to matching at Waves 2 (t= −3.60, p< .01) and 3 (t= −2.84, p< .01), but once youth are matched on 19 risk and protective factors that the causal link between depression and delinquency is no longer observed at either Waves 2 (t= −0.77, p< .44) or 3 (t= −0.49, p< .63).

Figure 1. Frequency of Delinquency Differences Before and After Matching for NonDepressed Youth (“control group”) and Depressed Youth (“treatment group”).

Note. Wave 2 Delinquency: Before Matching (t= −3.60, p <.01) / After Matching (t= −0.77, p= .44); Wave 3 Delinquency: Before Matching (t= −2.84, p <.01) / After Matching (t= −0.49, p= .63).

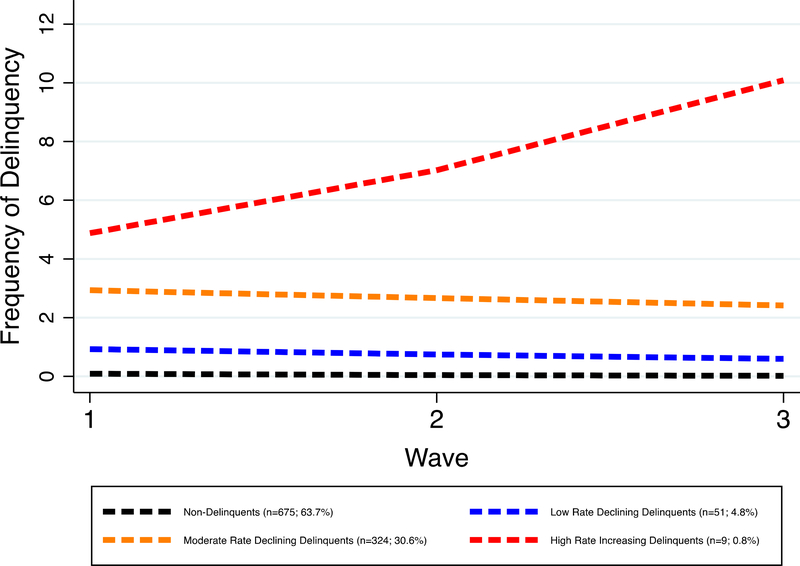

Figure 2 graphically depicts the four group, linear group-based trajectory model that was determined to be the most optimal model relying on the model selection criteria outlined by Nagin (2005, 2010) and described previously. The mean posterior probabilities for group assignment ranged from 0.82 to 0.99 (Table 2), which were well above the 0.70 threshold offered by Nagin (2005, 2010). This provided evidence that the trajectory model was estimated with a high degree of precision in its ability to assign youth to the appropriate group-based trajectory that best represented their individual trajectory of delinquency. The most prevalent trajectory group was the non-delinquents (63.7%). Comparatively, there were two trajectory groups that resembled one another in terms of having a declining trend in their delinquency frequency over time, with the main difference being that one was characterized as low rate declining delinquents (4.8%) and the other was classified as moderate rate declining delinquents (30.6%). The fourth trajectory group, representing the smallest percentage of the sample (0.8%) initially began committing an average of approximately 5 delinquent acts at Wave 1 and considerably escalated and more than doubled their average rate of delinquency by Wave 3. This pattern resulted in this trajectory group being labeled as high rate increasing delinquents.

Figure 2. Delinquency Trajectories.

Table 2.

Mean Posterior Probabilities for Delinquency Trajectory Assignments.

| Group | Non-Delinquents | Low Rate Declining Delinquents | Moderate Rate Declining Delinquents | High Rate Increasing Delinquents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Delinquents (n=675) | .89(.88−.89) | .11(.10−.12)) | .00(.00) | .00(.00) |

| Low Rate Declining Delinquents (n=324) | .11(.09−.13) | .83(.81−.84) | .06(.05−.07) | .00(.00) |

| Moderate Rate Declining Delinquents (n=51) | .00(.00) | .15(.11−.20) | .82(.79−.87) | .02(.01−.04) |

| High Rate Increasing Delinquents (n=9) | .00(.00) | .00(.00) | .01(.01−.02) | .99(.98–1.0) |

Note: Mean group-based posterior probabilities presented. 95% Confidence Intervals for mean group-based posterior probabilities in parentheses.

As displayed in Table 3, 14 risk and protective factors significantly distinguished the group-based trajectories of delinquency, and all of the trajectory groups significantly differed in their delinquency frequency across all three Waves. Generally speaking, the moderate rate declining delinquents and the high rate declining delinquents had higher levels of the risk factors (e.g., living in the Bronx, males, age, attitudes toward delinquency, sensation-seeking, peer delinquency, exposure to violence, coercive discipline, acculturation, negative school environment, locus of control, and stressful life events) and lower levels of the protective factors (e.g., positive parent-child interactions and social support) compared to the low rate delinquents and the non-delinquents. According to post-hoc tests, living in the Bronx, attitudes favorable to delinquency, sensation-seeking, exposure to violence, and acculturation were particularly salient risk factors distinguishing the high rate delinquents from both the low rate delinquents and the non-delinquents.

Table 3.

Delinquency Trajectories, Group Mean Covariate Levels: ANOVA Results.

| Variables | Non-Delinquents | Low Rate Declining Delinquents | Moderate Rate Declining Delinquents | High Rate Increasing Delinquents | F-test | Tukey’s ba |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site (Bronx=1) | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 6.67*** | G4>G1, G2, G3 |

| Gender | 1.52 | 1.42 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 4.73** | None |

| Age | 11.55 | 12.15 | 12.63 | 12.67 | 31.42*** | G3, G4>G1 |

| Attitudes toward delinquency | 1.88 | 3.42 | 6.73 | 7.00 | 43.17*** | G3, G4>G1, G2 |

| Sensation-seeking | 3.14 | 4.25 | 5.61 | 6.56 | 33.68*** | G3>G1; G4>G1, G2 |

| Self-esteem | 12.64 | 12.17 | 12.43 | 13.33 | 2.14 | None |

| Peer relationships | 4.33 | 4.25 | 4.24 | 3.78 | 1.38 | None |

| Peer delinquency | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 9.13*** | None |

| Parent-child interaction | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 3.08* | G4<G1, G2; G3<G1 |

| Exposure to violence | 1.59 | 3.38 | 5.39 | 6.89 | 51.23*** | G4>G2, G1; G3>G2, G1; G2>G1 |

| Coercive discipline | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 9.80*** | None |

| Cultural Stress | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 2.21 | None |

| Acculturation | 2.53 | 2.71 | 2.83 | 3.30 | 6.40*** | G4>G2, G1 |

| School environment | 2.70 | 3.78 | 4.31 | 4.44 | 15.35*** | None |

| Social support | 1.99 | 1.95 | 1.81 | 1.92 | 2.65* | None |

| Locus of control | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 9.56*** | None |

| Stressful life events | 0.65 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 1.56 | 6.25*** | G4>G1 |

| Welfare | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.63 | None |

| Delinquency (Wave 1) | 0.12 | 1.06 | 3.45 | 5.00 | 307.99*** | All groups significantly differ |

| Delinquency (Wave 2) | 0.00 | 0.73 | 2.84 | 8.56 | 653.48*** | All groups significantly differ |

| Delinquency (Wave 3) | 0.00 | 0.81 | 2.82 | 11.56 | 697.61*** | All groups significantly differ |

G1= Non-delinquents; G2= Low Rate Declining Delinquents; G3= Moderate Rate Declining Delinquents; G4= High Rate Increasing Delinquents.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

The final stage of the analysis is presented in Table 4. Model 1 (the unadjusted model) demonstrates that depression is a consistent factor that significantly distinguishes the offender trajectory groups from the non-delinquent trajectory group. Specifically, youth who are depressed have a higher likelihood of being assigned to a low rate declining delinquent trajectory (b= 0.303, se= 0.157, RRR= 1.350, p< .05), a moderate rate declining trajectory (b= 0.867, se= 0.302, RRR= 2.379, p< .001), or a high rate increasing trajectory (b= 1.998, se= 0.713, RRR= 7.375, p< .01) relative to a non-delinquent trajectory. In contrast, once the model was adjusted (Model 2) by controlling from the propensity scores derived from the range of risk and protective factors described previously, the discriminating effect of depression was only maintained for the high rate increasing delinquents (b= 1.388, se= 0.734, RRR= 4.006, p< .05). The fact that depression still exerted an independent effect on increasing the likelihood of a youth being classified as a high rate delinquent relative to being classified as a non-delinquent after adjusting for a host of confounders and potential selection effects demonstrates that depression is indeed a considerably robust risk factor for the most chronic forms of offending.

Table 4.

Distinguishing Delinquency Trajectories: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results.

| Group | Model 1: Unadjusted for Propensity Score b (se) IRR | Model 2: Propensity Score Adjusted b (se) IRR |

|---|---|---|

| Low Rate Declining Delinquents Depressed Youth | 0.303 (0.157) 1.350* | 0.019 (0.167) 1.019 |

| Moderate Rate Declining Delinquents Depressed Youth | 0.867 (0.302) 2.379** | 0.490 (0.318) 1.632 |

| High Rate Increasing Delinquents Depressed Youth | 1.998 (0.713) 7.375** | 1.388 (0.734) 4.006* |

| Likelihood Ratio Chisquare= Nagelkerke R2= | 17.174*** 0.020 | 71.227* 0.080 |

Note. Non-Delinquents are the reference trajectory group. b= Unstandardized coefficient; se= standard error; RRR=relative risk ratio.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Discussion

There has been a long-held belief that mental illness is, in part, related to involvement in antisocial behavior throughout the life-course, with depression being singled out as one specific mental illness related to both internalizing and externalizing problematic behaviors. Yet, this line of research has not been able to isolate a causal relationship between the two, in large part, because of potential selection problems. Furthermore, much of the research on the linkage between depression and antisocial behavior has been conducted on White and African-American samples, with very little research conducted on Hispanics. Accordingly, this study sought to extend this line of research by: (1) examining the relationship between depression and offending in a longitudinal manner from late childhood into middle-adolescence, (2) relying on a sample of Hispanics participating in two sites, Bronx, New York and San Juan, Puerto Rico, who were part of the Boricua Youth Study (BYS), and (3) utilizing a methodological design that sought to take into consideration the selection effect concern regarding the risk factors associated with the propensity for depression. Several key findings emerged from our study.

First, we detected that the likelihood of self-reported depression was related to a large variety of risk factors. This implies the need to take into consideration of the characteristics that may predict depression among youth that may also be correlated with the risk for delinquent involvement. In other words, there are significant differences between depressed and non-depressed youth that need to be taken into consideration before any relationships are estimated and conclusions reached surround the effect of depression on subsequent outcomes, including delinquency. Second, after adjusting for these differences using propensity score matching methods, we found that at the bivariate level, after matching, there were no differences in the variety of delinquency between depressed and non-depressed youth. Third, we next considered the extent to which the various risk and protective factors considered in the BYS were related to four distinct trajectories of offending, the results of which reported anticipated distinctions in typically appropriate direction. Finally, and most importantly, when we considered whether self-reported depression was able to distinguish between delinquency trajectories we found that without using the matched sample, there were anticipated differences between offending trajectories such that with an increasing offense profile the relationship between depression and membership in each delinquent group, compared to non-delinquents, became stronger. Yet, when we considered the sample matched via propensity score methods, the only estimate for which depression was able to significantly distinguish between groups was between the high rate increasing delinquent trajectory compared to the non-delinquent trajectory. This result highlights the robust linkage between depression and high rate and chronic offending.

We think that these findings bear import not just for the larger literature on the link between depression and antisocial behavior generally, but also for the research in criminology building on the base of work conducted among Hispanics more specifically—a group that has received very little research attention (Piquero, 2008a). Nevertheless, we are mindful of some limitations associated with our work that should be recognized. First, a strength of our research was our attention to potential selection issues for which we are able to address through propensity score matching. Yet, as is true of every matching-based study, we do not have every potential variable that may distinguish between depressed and non-depressed youth. Therefore, we encourage researchers to expand the reach of potential variables that may act as key discriminators. Second, the BYS data only capture children and adolescents as they enter this key period of the life-course. Therefore, we do not know if the sole relationship we observed between depression and the most high-rate offending trajectory would remain should the children be followed into and throughout adulthood. Third, and relatedly, the BYS measure of depression was self-reported and based on the previous year. Although this measurement strategy is consistent with prior Hispanic delinquency research (Maldonado-Molina et al., 2010a), the extent to which these findings would extend to more recent episodes of depression remains an area for future inquiry. Also, future research may wish to examine the relationship between various alternative measurements of depression and delinquency such as a clinical diagnosis (yes/no), a continuous measure of depression symptoms, and/or rely on a cut-off point such as one or two standard deviations below the mean to differentiate more frequent (and serious) depression symptomology when data permit.

With these limitations in hand, we think that our work offers an important contribution to the research that explores the relationship between depression and antisocial behavior— particularly among Hispanics. As we have seen here, the linkage is not as customary as assumed and may be only relevant to the most extreme delinquency patterns during the adolescent period.

Highlights.

-

*

Depression is linked to delinquency prior to matching.

-

*

After matching, the depression and delinquency link seems spurious.

-

*

Depression is linked to delinquency trajectories.

-

*

After matching, depression still linked with high rate delinquency.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health through grants RO-1 MH56401 (Hector Bird, principal investigator) and P20 MD000537–01 (Glorisa Canino, principal investigator) from the National Center for Minority Health Disparities, and the Institute for Child Health Policy at the University of Florida. We acknowledge the important contributions of Vivian Febo, PhD, Iris Irizarry, MA, Linan Ma, MSPH, and of all of the dedicated staff members who participated in this complex study. The authors would also like to extend an acknowledgement to Rolf Loeber for his very important role as a principal investigator in the original BYS study and his contributions to its research design and variable measurement.

Footnotes

Specifically, the youth in the current study were approximately ages 10–13 at Wave 1, ages 11–14 at Wave 2, and ages 12–15 at Wave 3.

It is important to note that this stage of the analysis mirrors the PSM estimation procedure described in the earlier stages of the analysis, with one exception. Specifically, baseline (Wave 1) delinquency was not included as a covariate in the estimation of these specific propensity scores as it was a part of the dependent variable used to estimate the trajectories.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Wesley G. Jennings, Email: jenningswgj@txstate.edu, Texas State University, School of Criminal Justice, College of Applied Arts, 601 University Drive Hines Room 108, San Marcos, Texas 78666, Phone: 512-245-3331, Fax: 512-245-8065.

Mildred Maldonado-Molina, Email: mmmm@ufl.edu, Health Outcomes & Policy, Clinical and Translational Research Building, 2004 Mowry Road, Suite 2250, University of Florida, P.O. Box 100177, Gainesville, FL 32610-0177, Phone: (352) 294-5797, Fax: (352) 294-5994.

Danielle M. Fenimore, Email: dmf83@txstate.edu, Texas State University, School of Criminal Justice, College of Applied Arts, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, Texas 78666, Phone: 512-245-2174 Fax: 512-245-8065.

Alex R. Piquero, Email: apiquero@utdallas.edu, University of Texas at Dallas, Program in Criminology, EPPS 800 W. Campbell Road, GR31 Richardson, TX. 75080, Phone: (972) 883-2482, Fax: 972-883-6297.

Hector Bird, Email: birdh@childpsych.Columbia.edu, Columbia University, Harkness Pavilion, 180 Ft. Washington Avenue New York, NY 10032, Phone: 646-774-5353, Fax: 646-774-5316.

Glorisa Canino, Email: glorisa.canino@upr.edu, Department of Pediatrics, Behavioral Sciences Research Institute, University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, PO Box 365067, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00936-5067, Phone: 787-754-8624, Fax: 787-767-5959.

References

- Armsden GC, McCauley E, Greenberg MT, Burke PM, & Mitchell JR (1990). Parent and peer attachment in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 683–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He JP, Burstein M, & Merikangas KR (2015). Major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement: prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Duarte CS, Febo V, Ramirez R, Hoven C, Wicks J, Musa G, & Loeber R (2006a). A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: I. Background, design, and survey methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 1032–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Davies M, Duarte CS, Shen S, Loeber R, & Canino GJ (2006b). A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: II. Baseline prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates in two sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 1042–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bird HR, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Chavez L, Alegria M, Bauermeister JJ, Hohmann A, Ribera J, Garcia P, & Martinez,-Taboas A (2004). The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: Prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E (2004). A statewide screening of mental health symptoms among juvenile offenders in detention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43, 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi Y, Roberts RE, Takeuchi K, & Suzuki S (2001). Multiethnic comparison of adolescent major depression based on DSM-IV criteria in a US-Japan study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1308–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D, Huizinga D, & Ageton S (1985). Explaining delinquency and drug use Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Tejera G, Canino G, Ramirez R, Chavez L, Shrout P, Bird H, Bravo M, Martinez-Taboas A, Ribera J, & Bauermeister J (2005). Examining minor and major depression in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 888–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH et al. (1998). Measurement of risk for mental disorders and competence in a psychiatric epidemiologic community survey: The National Institute of Mental Health Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 33, 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, & Weis JG (1981). Measuring delinquency. Beverly Hills, California: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfield P, Maschi T, White HR, Traub LG, & Loeber R (2006). Mental health and juvenile arrests: Criminality, criminalization, or compassion? Criminology, 44, 593–630. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson W (1992). The Walmyr Assessment Scales Scoring Manual. Tempe, AZ: WALMYR. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Maldonado-Molina MM, Piquero AR, & Canino G (2010a). Parental suicidality as a risk factor for delinquency among Hispanic youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 315–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Maldonado-Molina MM, Piquero AR, Odgers CL, Bird H, & Canino G (2010b). Sex differences in trajectories of offending among Puerto Rican youth. Crime & Delinquency, 56, 327–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, & Reingle JM (2012). On the number and shape of developmental/life-course violence, aggression, and delinquency trajectories: A state-of-the-art review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40, 472–489. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Fox B, & Farrington DP (2014a). Inked into crime? An examination of the causal relationship between tattoos and life-course offending among males from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Richards T, Smith MD, Bjerregaard B, & Fogel S (2014b). A critical examination of the “White victim effect” and death penalty decision-making from a propensity score matching approach: The North Carolina experience. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42, 384–398. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Richards T, Tomsich E, & Gover A (2015). Investigating the role of child sexual abuse in intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration in young adulthood from a propensity score matching approach. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24, 659–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Fridell LA, Lynch M, Jetelina KK, & Reingle Gonzalez J (2017). A quasi- experimental evaluation of the effects of police body-worn cameras (BWCs) on response-to-resistance in a large metropolitan police department. Deviant Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JH, & McKutcheon M (1980). Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the life events checklists In Johnson JH and McCutcheon M (Eds.), Stress and Anxiety (pp. 15–28). New York: Hemisphere Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, & Van Kammen WB (1998). Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Magafia JR, de la Rocha O, Amsel J, Magafia HA, Fernandez MI, & Rulnick S (1996). Revisiting the dimensions of acculturation: Cultural theory and psychometric practice. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 18, 444–468. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza RH (1989). An empirical scale to measure type and degree of acculturation in Mexican-American adolescents and adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 20, 372–385. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina MM, Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Bird H, & Canino G (2009). Trajectories of delinquency among Puerto Rican children and adolescents at two sites. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 46, 144–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina MM, Reingle JM, Tobler AL, Jennings WG, & Komro KA (2010). Trajectories of physical aggression among Hispanic urban adolescents and young adults: An application of latent trajectory modeling from ages 12 to 18. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 35, 121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hilt LM, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2007). Racial/ethnic differences in internalizing and externalizing symtoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 801–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Berstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, & Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Stydy- Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2013). Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 339–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan K, & Piquero AR (2009). Investigating the longitudinal relation between offending frequency and offending variety. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 653–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS (2010). Group-based trajectory modeling: An overview In Piquero AR and Weisburd D (Eds.). Handbook of Quantitative Criminology (pp. 53–67). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Olazagasti MAR, Shrout PE, Yoshikawa H, Canino GJ, & Bird H (2013). Contextual risk and promotive processes in Puerto Rican youths’ internalizing trajectories in Puerto Rico and New York. Development & Psychopathology, 25, 755–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Raven D, van Oort F, Hartman CA, Reijneveld SA, Veenstra R, Vollebergh WAM, Buitelaar J, Verhulst FC, & Oldehinkel AJ (2015). Mental health in Dutch adolescents: A TRAILS report on prevalence, severity, age of onset, continuity and comorbidty of DSM disorders. Psychological Medicine, 45, 345–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, & Robins RW (2013). Understanding the link between low self-esteem and depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 455–460. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR (2008a). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course In Liberman A (Ed.), The Long View of Crime: A Synthesis of Longitudinal Research (pp. 23–78). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR (2008b). Disproportionate minority confinement. The Future of Children, 18, 59–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR (2015). Understanding race/ethnicity differences in offending across the life-course: gaps and opportunities. Journal of Developmental and Life Course Criminology, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, & Rhode LA (2015). Annual Research Review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 345–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raia JA (1995). Perceived social support and coping as moderators of children’s exposure to community violence. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Los Angeles: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Reingle JM, Jennings WG, & Maldonado-Molina MM (2011). The mediate effect of contextual risk factors on trajectories of violence: Results from a nationally representative, longitudinal sample of Hispanic adolescents. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 327–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reingle JM, Maldonado-Molina MM, Jennings WG, & Komro KA (2012). Racial/ethnic differences in trajectories of aggression in a longitudinal sample of high-risk, urban youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51, 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, & Chen Y-W (1995). Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among Mexican-origin and Anglo adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology, 25, 95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR (2002). Observational studies (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, & Rubin DB (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observation studies for casual effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF et al. (1991). Preliminary development of a sensation-seeking scale for children. Personality and Individual Differences, 12, 399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF et al. (1993). A sensation-seeking scale for children: Further refinement and psychometric development. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 15, 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Santesteban O, Ramos-Olazagasti MA, Eisenberg RE, Wei C, Bird HR, Canino GJ, Duarte CS (2017). Parental Warmth and Psychiatric Disorders among Puerto Rican Children in Two Different Sociocultural Contexts. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 87, 30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraedley PK, Gotlib IH, & Hayward C (1999). Gender differences in correlates of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (1995). Stress, coping and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Special Issue, 53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]