Summary

Chronic pain is an important problem after critical care admission. Estimates of the prevalence of chronic pain in the year after discharge range from 14% to 77% depending on the type of cohort, the tool used to measure pain, and the time point when pain was assessed. The majority of data available come from studies using health-related quality of life tools, although some have included pain-specific tools. Nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain can occur in critical care survivors, but limited information about the aetiology, body site, and temporal trajectory of pain is currently available. Older age, pre-existing pain, and medical co-morbidity have been associated with pain after critical care admission. No trials were identified of interventions to target chronic pain in survivors specifically. Larger studies, using pain-specific tools, over an extended follow-up period are required to confirm the prevalence, identify risk factors, explore any association between acute and chronic pain in this setting, determine the underlying pathological mechanisms, and inform the development of future analgesic interventions.

Keywords: chronic pain, critical care, critical care outcomes, post-intensive care syndrome, rehabilitation

Over the last two decades, mortality during admission to intensive care has decreased.1, 2, 3 As a result, the challenges of ‘ICU survivorship’ have become an increasingly important focus.4 With between 216 and 2353 admissions to intensive care per 100 000 population in Europe and North America,5 and more than 270 000 UK critical care admissions in 2015–6,6 the long-term sequelae of ICU admission represent a significant health burden. Many long-term survivors of critical care admission display physical, mental, and cognitive impairments, now recognised as post-intensive care syndrome (PICS).7 Although there is no official definition of PICS, it is generally recognised as including new or worsening dysfunction in one or more of the following domains:

-

(i)

Physical function: including pulmonary or neuromuscular impairment, and reduced ability to walk or carry out activities of daily living

-

(ii)

Cognitive function: impairment in executive function, memory, mental processing, and visual–spatial perception

-

(iii)

Psychological function: depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

There is increasing evidence that chronic pain in ICU survivors may be an important mediator for the physical, cognitive, and psychological symptoms and signs associated with PICS, yet until recently the role of chronic pain in this cohort has received little attention. This article aims to provide a narrative review of the evidence for the prevalence, characteristics, aetiology, and therapeutic interventions for chronic pain after ICU admission, and to summarise future research priorities in this condition.

Methods

This narrative review consists of two components. Firstly, a literature search was conducted including PubMed, Medline, and Embase databases using the following study terms: ‘chronic pain’ or ‘quality of life’ AND ‘intensive care’ or ‘critical care’ or ‘survivors’. Only English language publications involving studies with adult humans were included. Studies conducted since January 1, 2000 were included to reflect contemporary critical care practice, but where these studies referenced older studies, these were also assessed for relevance (date of search: October 11, 2018). This was not intended to be a full systematic review addressing a specific question, as the aim was to provide a broad description of the topic and to highlight important areas for future research.

In an effort to increase the data available for this review, and to act as an illustration of data that may be available for secondary analysis, principal investigators of 25 recent UK-based critical care studies (published in the last 10 years), which included long-term follow-up and the collection of pain symptoms as part of a EuroQol-5D8 (EQ-5D) instrument, were contacted by the senior author. Whilst we acknowledge that there are likely differences globally, UK-based studies were selected, as it was anticipated that patients included would have access to broadly similar treatment pathways within the National Health Service after discharge (although wide regional variation is acknowledged), for example, access to general practitioners, pharmacies, chronic pain clinics, and emergency services for management of chronic pain. Principal investigators (PIs) were invited to submit ‘pain/discomfort’ EQ-5D data from baseline and any other subsequent time points. Data reported using the 5L format of the EQ-5D were converted to the 3L format as follows: ‘no pain or discomfort’ remained the same, ‘slight’ and ‘moderate’ pain or discomfort were converted to ‘moderate’ pain, and ‘severe’ and ‘extreme’ pain converted to ‘extreme’ pain. As this was not a systematic search for data, a formal meta-analysis was not performed, but data were summarised in a proportional format for prevalence of symptoms for each study cohort.

Prevalence

Chronic pain after intensive care admission was first described in cohort studies examining health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in the months and years after ICU discharge. Whilst the majority of these studies did not collect pain-specific outcome data, pain was reported as a commonly problematic HRQoL domain9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 with tools, such as the EQ-5D8 and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).19 A limited number of studies have been conducted with the primary aim of exploring chronic pain in ICU survivors.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 One such study24 has recently suggested the use of the term ‘chronic ICU-related pain’ (CIRP) to describe pain that persists for at least 3 months post-ICU discharge, in keeping with the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) definition of chronic pain,27 and this will be used as the definition to discuss prevalence in this review.

Estimates of the prevalence of chronic pain in ICU survivors range from 14% to 77% depending on the population, the time point when outcomes were evaluated post-discharge, and the type of tool used.11, 14, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 In common with other long-term outcomes in ICU survivors, it is important to appreciate the premorbid state of the patient, so that the impact of the intensive care admission itself on the development, or mediation, of chronic pain can be elucidated.

Comparison with the premorbid state is challenging, as ICU admission is often not planned, thereby preventing prospective pre-admission data collection. As a consequence, the reporting of the pre-admission presence or absence of pain relies either on the retrospective recall by the patient, or on the proxy reporting by relatives or friends. Both methods may be subject to bias for many reasons, and it is not clear which is most reliable.33, 34 Studies that use these methods to specifically define ‘new onset’ chronic pain after ICU admission report prevalence of between 22% and 33%.22, 24

Chronic pain is also a condition that affects a significant proportion of the general population35; therefore, to infer a greater prevalence in ICU survivors, comparison with a control group where other risk factors, such as age and co-morbidity profile, are adjusted for is required. Comparison with appropriate control groups has been performed in several studies examining the long-term consequences of ICU admission, as normative data sets exist for the SF-36 and EQ-5D, but in studies where pain was the main outcome of interest, none have attempted to directly compare the prevalence of pain to matched control groups.16, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26 Data from simple ‘population normal’ studies are of arguable value, as the co-morbidity burden, which predisposes to emergency admission to critical care, is substantial, rendering the critical care population not ‘normal’. Thus, estimates from simple case control studies are unlikely to be very accurate.

With the preceding caveat in mind, in line with other HRQoL domains, pain does appear to be significantly more prevalent in the post-ICU population than in normative data sets.13 Using the EQ-6D in a Dutch population, Timmers and colleagues14 identified that pain and discomfort were the most frequently reported domain, with 57% of patients reporting problems compared with 34% in the general population. However, Orwelius and colleagues30 showed that the effect of ICU admission on the proportion of patients reporting pain (44.3% of the post-ICU population vs 25.7% of those that were not admitted to the ICU) was mitigated once the number of pre-existing co-morbidities was accounted for in the reference population. A systematic review of HRQoL after ICU discharge, including 48 studies,18 identified a significant decrement in pain domains compared with population norms when using the EQ-5D at 12 months (20 studies). However, when the SF-36 was used (30 studies), this decrement was not significant, and it is unclear whether the different results can be accounted for by the choice of outcome measure or other study-specific characteristics.

Core outcome sets have been defined for research in rehabilitation of ICU survivors and acute respiratory failure survivors specifically.36, 37 Although these recommendations stress the importance of including measures for recording pain, no validated pain measures, other than a VAS, are specifically recommended.36, 37 This may be attributable to the fact that so few studies exist using pain-specific tools common in chronic pain research in ICU survivor populations. It is generally considered that the use of the VAS as a measure of pain intensity fails to evaluate the multidimensional complexity of a condition, such as chronic pain.38

In studies where pain has been at the centre of the hypotheses, the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)39 has been used most frequently, and one study each reported the German Pain Questionnaire40 and the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire.41 Needham and colleagues37 reflect that pain-specific measures, in addition to core HRQoL measures, should be included in the future research agenda.37 Such research will undoubtedly require joint working between clinical and basic science researchers from both chronic pain and intensive care.

Pain intensity

Pain intensity has long been recognised as a core outcome in clinical research,42 and it is advised that severity is recalled over different periods of time and with respect to different functional domains, for example, with the Von Korff and colleagues43 pain grading or the chronic pain grade questionnaire44; however, this level of detail has rarely been reported in studies involving ICU survivors.

One study that did use the Von Korff and colleagues43 grading revealed that more than 50% of patients with CIRP reported high disabling pain with moderate (21.2%) to severe (36.4%) limitation in daily living.24 Several studies do report some other measures of pain intensity. Moderate-to-severe pain, measured on the BPI, was reported in 31% of 295 medical and surgical ICU patients at 3 months post-discharge, which increased to 35% at 1 yr.25 Marx and colleagues21 also used the BPI, and reported 44% of sepsis patients scoring pain intensity of 0–3/10 and 56% 4–10/10. From the EQ-5D, it is possible to determine whether patients report pain as ‘slight’, ‘moderate’, ‘severe’, or ‘extreme’ if the 5L version is used (or ‘no’, ‘moderate’, or ‘extreme’ pain if the 3L version is used). Although most studies do not describe this level of detail, Granja and colleagues45 identified 33% of their cohort as reporting moderate and 7% extreme pain/discomfort on EQ-5D.

From the SF-36, it is also possible to determine a numerical ‘bodily pain’ 0–100 score, where higher values indicate a more favourable status. Although this cannot be taken as a proxy for pain intensity, it could provide quantitative information about pain impact. Herridge and colleagues46 reported a median bodily pain SF-36 score of 62/100 and 74/100 at 1 and 5 yr, respectively. A pooled estimate of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) studies reporting the SF-36 calculated a decline in bodily pain score over 1–4 yr post-discharge of 20.47 It is not clear to what extent such changes in a numerical HRQoL bodily pain subdomain infer a clinically meaningful change in ICU survivors.

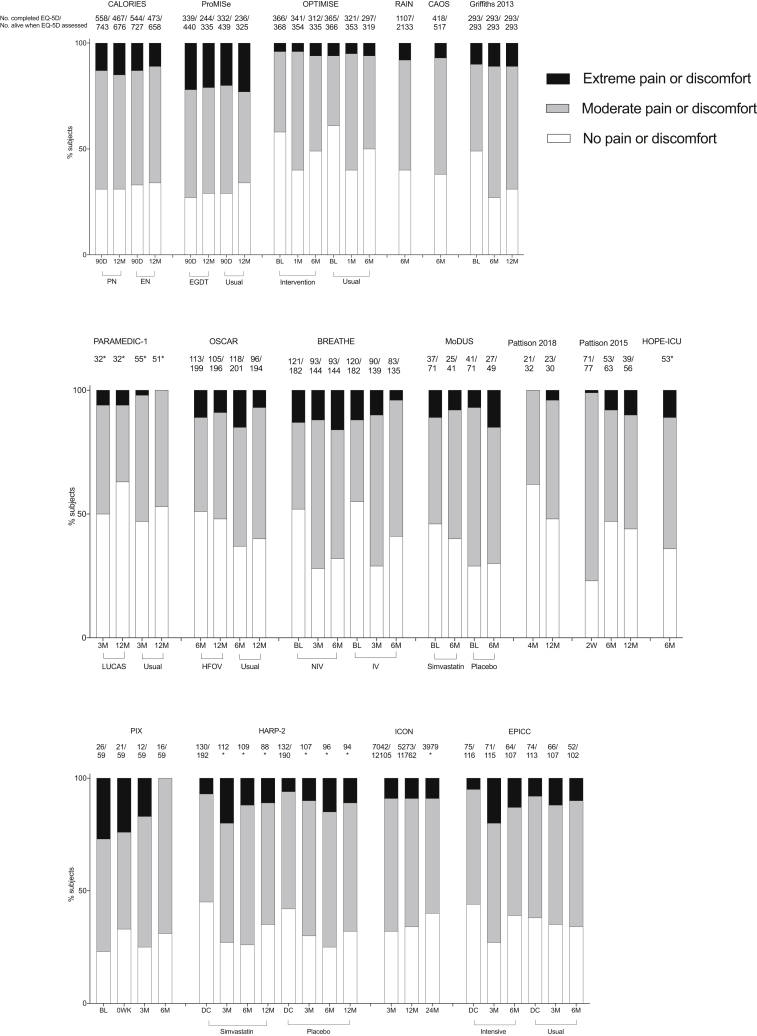

To increase our understanding of pain prevalence and severity in ICU survivors across a range of cohorts, we have collated EQ-5D scores from more than 12 000 patients in recently published UK-based studies (Table 1; Fig. 1). This was to illustrate data relating to pain or discomfort that were collected, but may not have been published in the original reports. Of the 25 studies identified, the investigators were able to contribute data from 17 (68% response rate). The data indicate that at least moderate pain or discomfort is common during the first year after ICU admission across many different patient cohorts, and that a variable proportion report extreme symptoms. The Optimisation of Cardiovascular Management to Improve Surgical Outcome (OPTIMISE) study is illustrative of a study that recruited only surgical patients, yet it does not appear to stand out as having a very different proportion of patients with pain after discharge.48

Table 1.

Summary of studies contributing data to the evaluation of reported pain symptoms shown in Figure 1. All studies were conducted in the UK, and recruited patients were from units in the UK or The Republic of Ireland. CCU, critical care unit; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DOH, Department of Health; EME, Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme; ESICM, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HFOV, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; HRB, Health Research Board; HSC R&DD, Health and Social Care Research & Development Board; ICHT, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust; ICIS, Intensive Care Society of Ireland; ICNARC, Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre; MRC, Medical Research Council; NHS, National Health Service; NIHR BRC, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre; NIHR-CS, NIHR Clinician Scientist Award; NIHR-HTA, National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme; OPTIMISE, Optimisation of Peri-operative Cardiovascular Management to Improve Surgical Outcome; RfPB, Research for Patient Benefit programme; R&D, Research and Development; TBI, traumatic brain injury

| Study | Funding | Population | Intervention | Comparator | Outcome | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvey and colleagues49 (2016) (CALORIES) | NIHR-HTA | 2400 adult patients (329 surgical); unplanned CCU admissions | 5 days early parenteral nutritional support, n=1200 | 5 days early enteral nutritional support n=1200 | No significant difference in 30 day all-cause mortality | Multicentre RCT |

| Mouncey and colleagues50 (2015) (ProMISe) | NIHR-HTA | 1260 adult patients (no surgical patients); septic shock | Early goal-directed therapy, n=630 | Usual resuscitation, n=630 | No significant difference in 90 day all-cause mortality | Multicentre RCT |

| Pearse and colleagues48 (2014) (OPTIMISE) | NIHR-CS | 734 adult patients (all surgical); >50 yr; high risk undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery | Cardiac-output-guided haemodynamic therapy algorithm for i.v. fluid and inotrope (dopexamine) infusion, n=368 | Usual care, n=366 | No significant difference in 30 day mortality, complications | Multicentre RCT; updated systematic review and meta-analysis, including RCT data |

| Harrison and colleagues51 (2013) (RAIN) | NIHR-HTA | 3210 adult patients; admitted to the CCU after actual/suspected TBI; GCS score of <15 | N/A | Comparison of type of critical care unit where care was delivered | Results suggest neuro-CCU management may be cost-effective | Multicentre, prospective cohort study |

| Wildman and colleagues52 (2009) (CAOS) | MRC Health Services Research Fellowship; NHS R&D grant | 832 adult (no surgical patients); >45 yr old; breathlessness, respiratory failure, or change in mental status attributable to an exacerbation of COPD, asthma, or both | N/A | N/A | Pre-CCU data can aid prediction of 180 day mortality; high burden of symptoms at 180 days post-admission | Multicentre, prospective observational cohort study |

| Griffiths and colleagues53 (2013) | DOH; Oxford Health Charity; NIHR BRC (Imperial and Oxford) | 293 patients (173 medical, 89 surgical, 30 trauma, and 1 unknown); >16 yr | N/A | N/A | 12 months after discharge negative impact on employment and negative impact on family income | Multicentre, prospective cohort study |

| Ji and colleagues54 (2017) (PARAMEDIC-1) | NIHR-HTA | 1035 adult patients (no surgical patients); out-of-hospital cardiac arrest | LUCAS mechanical chest compression device, n=658 | Manual chest compressions, n=377 | No clinically important differences in long-term outcomes | Multicentre, cluster randomised trial |

| Lall and colleagues55 (2015) (OSCAR) | NIHR-HTA | 795 adult patients (108 surgical); mechanically ventilated patients with ARDS | HFOV (Novalung R100 ventilator) until the start of weaning, n=398 | Conventional ventilation, n=397 | HFOV had no effect on 30 day mortality and no economic advantage | Multicentre RCT |

| Perkins and colleagues56 (2018) (BREATHE) | NIHR-HTA | 364 adult patients (no surgical patients); mechanically ventilated and failed spontaneous breathing trial failed | Protocolised weaning via early extubation to non-invasive ventilation, n=182 | Protocolised standard weaning, n=182 | Early extubation to non-invasive ventilation (intervention group) did not shorten time to liberation from any ventilation | Multicentre, randomised, allocation concealed, open-label clinical trial |

| Page and colleagues57 (2017) (MoDUS) | NIHR | 142 adult patients (no surgical patients); mechanically ventilated | Simvastatin 80 mg daily (<28 days), n=71 | Placebo daily, n=71 | No difference in duration of delirium and coma | Multicentre RCT |

| Pattison and colleagues58 (2018) | Supported by The Royal Marsden BRC infrastructure | 50 adult cancer patients | Diary administration | N/A | Diaries can be a means of emotional support for patients post-ICU discharge | Single centre; mixed (qualitative and quantitative); observational |

| Pattison and colleagues59 (2015) | ESICM, European Critical Care Research Network, Edwards Nursing Science Award | 77 adult cancer patients; critical care stay >48 h | N/A | N/A | Patient shaped by ongoing illness and treatment | Single centre; mixed (qualitative and quantitative); observational |

| Page and colleagues60 (2013) (HOPE-ICU) | NIHR | 141 adult patients (50 surgical); mechanically ventilated | Haloperidol, irrespective of coma or delirium status, n=71 | Placebo: saline IV TDS 0.9%, n=71 | Haloperidol did not modify duration of delirium in critically ill patients | Single-centre RCT |

| Batterham and colleagues61 (2014) (PIX) | NIHR RfPB | 59 adult patients (8 surgical); mechanically ventilated | Supervised, hospital-based aerobic training intervention, n=29 | Usual care, n=30 | Accelerated short-term natural recovery process in intervention group; feasible | Multicentre, exploratory parallel-group controlled trial |

| McAuley and colleagues62 (2014) (HARP-2) | NIHR-EME, HRB, HSC R&DD, ICSI, REVIVE | 540 adult patients; ARDS | Simvastatin 80 mg daily (maximum of 28 days), n=259 | Placebo once daily, n=281 | Simvastatin did not improve clinical outcomes in ARDS | Multicentre RCT |

| Hatch and colleagues63 (2017) (ICON) | Intensive Care Foundation; Bupa Foundation | Pain data provided for 7325 adult patients; medical and surgical | Questionnaire follow-up for responses at either 3, 12, or 24 months | N/A | Questionnaire burden; had no effect on return rates; affected answers to the same questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L) | Multicentre, parallel-group RCT |

| Wright and colleagues64 (2018) (EPICC) | NIHR RfPB | 308 adult patients (148 surgical); invasive or non-invasive ventilation | Target of 90 min of physical rehabilitation per weekday, n=150 | Target of 30 min of physical rehabilitation per weekday, n=158 | ICU-based physical rehabilitation did not improve physical outcomes at 6 months | Multicentre, parallel-group RCT |

CALORIES, Trial of the Route of Early Nutritional Support in Critically Ill Adults; ProMISe, Protocolised Management in Sepsis; RAIN, Risk Adjustment in Neurocritical Care; CAOS, COPD and Asthma Outcome Study; PARAMEDIC-1, pre-hospital randomised assessment of a mechanical compression device in cardiac arrest; OSCAR, OSCillation in ARDS; BREATHE, Extubation to Non Invasive Ventilation for difficult to wean patients; MoDUS, Modifying Delirium Using Simvastatin; HOPE-ICU, HalOPEridol Effectiveness in ICU delirium; PIX, Post Intensive care eXercise; HARP-2, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibition with simvastatin in Acute lung injury to Reduce Pulmonary dysfunction; ICON, Intensive Care Outcomes Network; EPICC, Intensive versus standard physical rehabilitation therapy in the critically ill.

Fig 1.

Proportion of subjects reporting no, moderate, and extreme pain or discomfort after ICU admission. *Indicates that the authors did not have access to the number of subjects alive at the time point. The detailed reasons for missing data were also not known to the authors. BL, baseline; DC, at discharge; EGDT, early goal-directed therapy; EN, enteral nutrition; HFOV, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; Int, intervention; IV, invasive ventilation; LUCAS, LUCAS Chest Compression System; M, month; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; PN, parenteral nutrition; W, week. Full references for included studies are indicated in Table 1.

Temporal trajectory of pain

The trajectory of chronic pain after discharge is also unclear. Although one meta-analysis reported improvement in pain by 7 months when described using the SF-36, it also indicated that there was no significant improvement in pain at 12 months when EQ-5D results were analysed.11 Similar EQ-5D results were reported in the subpopulation analysis of patients with ARDS.47 In a more recent systematic review, little change in SF-36 bodily pain scores was identified after 9 months, yet on EQ-5D the proportion of patients reporting pain increased until 1 yr, after which no data were reported.18 Hayhurst and colleagues25 demonstrated a reasonably stable proportion of patients reporting pain, and consistent intensity and interference scores over the first year post-discharge using the BPI.

A growing number of studies with longer follow-up time (>1 yr) after discharge are being reported. Cuthbertson and colleagues13 demonstrated a trajectory using SF-36 bodily pain scores, where pain initially improves at 1 yr, but then deteriorates again at 5 yr. However, at 5 yr, Herridge and colleagues46 reported a slightly improved median (SF-36) pain score compared with 1 yr. One study in a surgical population reported an incidence of chronic pain of 57% as long as 8 yr after discharge, but did not report whether this was significantly higher than the control population.14

Pain trajectory may well be population specific, and cardiac ICU admission in particular appears to be unique. A multicentre cohort study of cardiac ICU patients reported an incidence of chronic pain of 40% at 3 months that decreased to 9.5% by 2 yr.23

Pain aetiology

The cause of chronic pain in ICU survivors is largely inferred from studies examining the sites of pain and risk factors associated with the onset of pain. There is evidence for the presence of nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain in ICU survivors. Nociplastic pain is a new mechanistic descriptor adopted by the IASP to define pain that ‘arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain’.65 This type of pain would include those reporting more non-specific, diffuse pain with no obvious cause for the activation of nociceptors or neuropathy.

Potential sources of acute pain are frequent in the ICU, and it is hypothesised that sustained, under-treated acute pain may contribute to a transition to chronic pain, similar to the process recognised in chronic post-surgical pain.66 One study has shown that those with CIRP reported higher pain intensity and distress scores when recalling their ICU experience,67 but, as yet, there is little evidence linking acute objective pain scores during admission to the development of chronic pain post-discharge. The ability to link acute and chronic pain in the ICU may be in part hampered by an infrequent or inappropriate assessment of pain during ICU admission,68 although it is hoped that updated guidelines69 and prioritising acute pain assessment in the critically ill may improve this.

In a single-centre general ICU questionnaire-based study, Battle and colleagues22 reported that the most frequently reported site of pain at 6 months post-discharge was the shoulder (22%), indicating a higher prevalence of chronic shoulder pain than that identified in the general UK population (11.7%).70 Limitation of shoulder movement was also commented on by Herridge and colleagues46 in their study of long-term follow-up of patients with ARDS. Recently, Gustafson and colleagues116 sought to identify the prevalence and risk factors for shoulder impairment post-ICU admission. More than 50% reported shoulder pain at 6 months, and 95% had reduced range of movement.

The other body sites highlighted as painful by Battle and colleagues22 included the lower limb (9%), lumbar spine (9%), cervical spine (6%), upper limbs (6%), abdomen (4%), and pelvis (3%).

Sepsis was also found to associate with the development of chronic pain, and it was suggested that increased time on inotropic support could lead to later instigation of rehabilitation. The inflammatory state associated with sepsis also mediates neurological damage, as demonstrated in critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP).71, 72 Many of the small molecules important in inflammation, including neuropeptides and cytokines, are pro-nociceptive. They could lead to the development of chronic pain through altering membrane excitability, descending nociceptive control, and synaptic plasticity.66, 73 ICU-related weakness secondary to immobility, CIP, and critical illness myopathy (CIM) can result in rapid deconditioning and potentially joint-related pain74 and contractures.22, 75

The hypothesised microcirculatory and metabolic derangement identified in CIP can affect sensory and motor transmission.76 Sensory impairment, such as numbness and tingling in glove and stocking distributions, has been reported after ICU discharge and suggest a neuropathic origin.76, 77, 78 Abnormal nerve conduction studies (NCS) have been reported up to 5 yr after ICU admission.79, 80 Sensory symptoms and signs can also be identified in the absence of abnormal neurophysiological testing, suggesting small fibre impairment, and have been shown to persist for up to 2 yr.78

Recently, three studies have sought to find evidence of structural abnormalities of small nerve fibre architecture through the assessment of intra-epidermal nerve fibre density (IENFD) on lower limb skin biopsy in ICU patients. Latronico and colleagues81 described reduced IENFD in 14 patients a month after admission, despite a range of NCS findings and not all exhibiting features of CIP or CIM. Skorna and colleagues82 performed serial skin biopsies in patients with normal NCS on ICU admission, and also showed a reduction in IENFD. However, only one study performing biopsies a significant time after discharge has been published83 and included only four patients at four months. It could not show a significant reduction in IENFD when compared with normative data, despite patients reporting paraesthetic symptoms. All of these studies were small, had a relatively short follow uptime and collected only limited patient-reported outcome measures with respect to neuropathic symptoms.

Although IENFD provides an objective structural measure of small fibre pathology, in some chronic pain conditions it has been shown to correlate poorly with patient-reported symptoms.84 Quantitative sensory testing (QST) is commonly used in neuropathic pain to provide an assessment of small fibre function,85, 86 and in some conditions can be correlated to IENFD.87 In a recent study, Baumbach and colleagues88 sought to determine evidence of small nerve fibre dysfunction using QST in 84 critical care survivors at 6 months post-discharge. Small fibre dysfunction was detected in 42.5% of patients, and was associated with significantly higher pain intensity, increased pain-related disability, and decreased HRQoL.

These studies suggest a role of small fibre dysfunction in CIRP, but larger studies using a more complete battery of tests and patient-reported outcomes for neuropathy and associated neuropathic pain are needed.

It is not clear if ICU survivors report multiple sites of pain. Generalised or multisite chronic pain is a common phenomenon observed in certain chronic pain populations,89, 90 and suggests a central augmentation of sensory processing.

Potential risk factors

The presence of pre-existing painful conditions has been associated with the development of new onset chronic pain after ICU admission.23, 24 This reflects evidence from general chronic pain populations that show high proportions of coexisting chronic pain conditions,91 but findings within ICU survivors are not consistent.22 The contribution of the number of pre-admission co-morbidities to long-term HRQoL after ICU admission is well documented,15, 30, 92 and Griffith and colleagues17 were able to demonstrate that pain specifically was associated with more medical co-morbidity. There is conflicting evidence to associate traditional measures of illness severity in ICU patients, such as number of days of mechanical ventilation20, 22 and length of stay on ICU14, 22, 23 with chronic pain. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score has not been associated with chronic pain,17 whilst an increased length of hospital stay has.20, 22

Several features of PICS,7 such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, and cognitive impairment, have well-recognised co-prevalence with chronic pain.91, 93, 94, 95 The relationship between pain and psychological distress is, however, bidirectional, which makes determining causality complex. ICU trauma patients with chronic pain report more symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety,31 and patients with chronic pain after cardiac surgery self-report lower mental health scores in the SF-36 a year after discharge.96 However, relationships between those experiencing chronic pain and adverse psychological outcomes after ICU admission are yet to be properly explored, making it difficult to tease out the influence of the ICU environment, the cause of ICU admission, psychological factors, and pain on each other.

Battle and colleagues22 were able to demonstrate on multivariate analysis that older age was associated with CIRP at 6 months. Although the influence of age on functional outcomes after ICU has been explored, pain, as assessed by HRQoL measures, was previously shown not to be influenced by age.11 This is in contrast to the association demonstrated between younger age and chronic postoperative pain,97 which has also been identified in cardiac post-surgical patients.23 A frequently cited hypothesis for this is that there is an age-dependent decline in peripheral nociceptive function; however, in ICU, other factors associated with age may be more important, such as reduced muscle mass or poorer nutritional status.17, 97

In recent years, an emphasis has been placed on the role of opioid exposure as a risk factor for the development of CIRP. In a general ICU population, exposure to opioids during admission was shown not to be significantly associated with the development of pain or the severity of pain interference.25 There is evidence from surgical populations that pre-surgical opioid use is associated with an increased risk of postoperative opioid use and misuse,98 and a large retrospective epidemiological study in Canada identified pre-admission opioid use (in 6.2% of admissions) was a significant predictor of opioid use at 1 yr post-ICU discharge.99 A further study showed that 5% of the elderly population admitted to the ICU was taking chronic opioids and that 63% continued to use them post-discharge. Those most likely to continue opioids were medical patients who were using fentanyl and benzodiazepines at admission.100

Specific ICU populations

Longitudinal cohort studies to identify risk factors for CIRP have indicated that a diagnosis of sepsis is associated with the development of chronic pain22 and more severe symptoms,16 although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. However, a recent case-control study, comparing more than 200 sepsis and non-sepsis patients, failed to demonstrate a significant difference in prevalence of new-onset chronic pain at 6 months post-discharge,22 and in another cohort, an admission diagnosis of sepsis was not shown to confer higher risk than trauma for the development of chronic pain.29 Marx and colleagues21 sought to characterise chronic pain in survivors of sepsis, and showed relatively high pain interference scores for interference with work (mean: 5.1/10) and general activities (mean: 4.2/10). Although it might be assumed that surgical patients would be at higher risk of CIRP as a result of an acutely painful intervention, Soliman and colleagues16 demonstrated that medical patients reported the lowest HRQoL at 1 yr, and that the greatest contributors to this decrement were pain and discomfort. However, this study did not control for pre-existing co-morbidities.

Survivors of ARDS are often studied as a discrete cohort for long-term follow-up. In an ARDS-specific meta-analysis of HRQoL (13 cohorts),47 patients reported more pain than the general population, and showed that pain continues to deteriorate at least to 12 months post-discharge. However, a more recent study, reported by Herridge and colleagues46 showed an improvement in pain between 1 and 5 yr.

The systematic review by Dowdy and colleagues11 identified that trauma patients reported more severe pain and discomfort in the EQ-5D compared with other ICU survivors, and Timmers and colleagues14 identified that 60% of trauma patients reported pain at a median of 8 yr follow-up, the highest prevalence of all subgroups of a Dutch surgical ICU population. Pavoni and colleagues101 also reported a high prevalence (79%) of chronic pain 1 yr after ICU admission for severe burns.

Persistent postoperative pain after cardiac surgery, commonly involving critical care admission, has been well investigated and is comprehensively discussed elsewhere.102 A recent systematic review103 highlighted that a pooled estimate of 37% of patients reported persistent pain at 6 months and 17% at least 2 yr after cardiac surgery, that neuropathic pain was common, and that more than half of those with pain experienced moderate-to-severe symptoms. An association between length of stay in the ICU and the severity of persistent pain after cardiac surgery has also been demonstrated, suggesting that either length of stay was a proxy for disease complexity or severity, or that ICU-specific features in the patient journey have an important influence on pain outcome.

Impact of chronic pain

The impact of chronic pain after ICU has mostly been explored through the use of measures of functional impairment and healthcare utilisation. Hayhurst and colleagues25 reported a high proportion of patients describing pain-related functional interference with daily activities at 3 and 12 months (59% and 62%), but interference was generally mild (median of 2/10), lower than that reported by Marx and colleagues21 (mean interference with daily activities: 5.1/10). Thirty-two per cent of those reporting pain at 6 months in the UK-based Battle and colleagues22 study reported seeking the advice of a healthcare professional to manage their pain, and 45% of participants in a Dutch cohort study had sought access to a multidisciplinary programme to address their functional needs, including pain by 3 months.104

Interventions to manage chronic pain

To our knowledge, no RCTs have been conducted with the specific aim of reducing chronic pain after ICU admission. Theoretically, interventions could be targeted during acute admission to modify potential risk factors, such as acute pain, or during interaction with healthcare professionals as part of post-ICU follow-up. The evidence for early and post-discharge rehabilitation interventions on long-term outcomes has been subject to a review of systematic reviews.105 This identified that patients may derive short-term benefits from early interventions, and that there was insufficient evidence to support post-discharge interventions; however, pain was not mentioned as a specific outcome in this review. Frustratingly, although the majority of the original studies included collected pain data in the form of HRQoL indices, very few specifically reported pain subdomains or perform statistical analysis on the data. Walsh and colleagues106 were an exception to this, but showed no significant difference in pain scores up to 1 yr between ICU subjects that underwent an enriched, individualised exercise and nutritional rehabilitation programme, and those following usual care. The lack of availability of pain-specific data may change, as the recommendations for core outcome sets to include pain measures are integrated into new study protocols.36, 37

The development of interventions targeted at pain is likely limited by the lack of evidence for the pathophysiological mechanisms involved and as yet conflicting evidence for modifiable risk factors associated with the development of pain specific to this population. Transferring any post-discharge intervention into clinical practice is also likely to be impeded by the inconsistent provision of ICU follow-up services,107 despite the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendation108 and the fact that pain specialists are rarely included in such services.

Future research priorities

In common with all research investigating the long-term consequences of ICU admission, the loss to follow-up attributable to mortality and disengagement with outpatient services can impact on response rates, meaning that very large initial sample sizes may be required to detect statistically meaningful effects. There is also likely to be a bias in those that do respond, dependent on the research question. Similarly, the challenge of collecting pre-admission pain-related information, potentially both patient-reported and objective measures, such as QST, must be overcome or accounted for, and the use of patient recall or proxy reporting of chronic pain investigated.

Data from very-long-term follow-up are emerging, but are still lacking, especially with respect to validated pain measures. If cancer survivorship is used as a comparison, long-term follow-up studies commonly start at 5 yr. Ideally, longitudinal cohorts should incorporate multi-aetiology and multicentre designs to allow for assessment of the impact of disease- and service-specific factors on the development of chronic pain. Certain ICU cohorts, such as those with traumatic brain injury or cognitive impairment, are often excluded from long-term follow-up studies, but chronic pain may well be particularly prevalent in those with neurological pathology. Innovative studies to include such populations are required to estimate the prevalence and identify risk factors to inform the design of interventions.

The accurate and interpretable recording of multisite pain is challenging, yet is likely to be important in this population. Novel web-based or electronic forms of recording painful sites may be useful to assess the spatial burden of pain and aid the determination of pain aetiology. Although pain measures, such as VAS, for pain intensity have been recommended for clinical research in ICU survivors,36 studies, including other validated pain measures, commonplace in the chronic pain research arena, to assess pain characteristics and impact could provide valuable information about pain aetiology and functional impairment, and reflect more comprehensively the complex condition that is chronic pain. The reporting of subdomains of commonly collected HRQoL data relating to pain could also improve our understanding of pain without increasing the data collection burden. Concluding which measures are most relevant in this unique cohort will require further investigation and a consensus agreement across specialists in both the pain and critical care fields.

Chronic pain has the potential to mediate all areas of PICS and the complex interplay between the cognition, psychological, and social sequelae, and physical impairment, in this cohort. This needs to be explored further in order to provide patients with a holistic approach to rehabilitation. An awkward confounder is the quantity and effectiveness, or otherwise of pain medication and services that patients may have accessed; being free of pain, but taking large doses of analgesics is not the same thing as being genuinely free of pain, but may result in the same score being entered into a questionnaire or scale.

There is currently limited evidence linking acute and chronic pain in ICU survivors. It is recognised that good acute pain assessment and management are associated with improved acute outcomes,109, 110, 111, 112 yet several studies have identified that acute pain management in ICU remains poor in many parts of the world.68, 113, 114, 115 A coordinated approach in response to new acute pain management guidelines69 could alter the trajectory of chronic pain in this population.

Larger deep profiling studies incorporating subjective and objective measures in the same subjects are also needed to provide information on pain-generating mechanisms contributing to symptoms in the ICU survivors. It is likely that the mechanisms are heterogeneous given the diversity of the population, admitting diagnoses, and the different courses of ICU treatment. Methods for identifying those at risk of developing chronic pain and stratifying this heterogeneity could lead to clinically relevant tools to improve pain management during acute and chronic phases of the patient pathway. Chronic pain in the ICU is a common and debilitating problem, yet no interventions have yet been developed or subjected to clinical trial. It is anticipated that, as our understanding of the pathological mechanisms and risk factors improves, such interventions can be designed and integrated into rehabilitation programmes.

Authors' contributions

Literature search: HIK.

Drafting manuscript: HIK, HL.

Conducted the search of studies that contributed data to the sub-analysis, contacted the study teams, and devised the idea: AC, SJB.

Extracted and collated data from information sent by study teams: AC.

Editing and contributing to the final version of the manuscript: all authors.

The collaborators listed extracted, and sent summary data, from their original studies to AC and SJB for inclusion.

Acknowledgements

Collaborators: KM Rowan, A Richards-Belle, R Lall, D Young, GD Perkins, N Pattison, DF McAuley, C McDowell, A Agus, VJ Page, S Bonner, K Hugill, SV Baudouin, SE Wright, RA Hatch, and PJ Watkinson. SJB is grateful for the support of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or Department of Health.

Handling editor: J.G. Hardman

Editorial decision: 19 March 2019

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Data represented as the HARP-2 study generated by UK Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Programme (EME 05:01 Simvastatin to reduce pulmonary dysfunction in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: the HARP-2 RCT), an MRC and NIHR partnership (08/99/08). The EME Programme is a collaboration between the MRC and NIHR, with contributions from the Chief Scientist Office in Scotland, the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research in Wales, and the Health and Social Care (HSC) Research and Development Division, Public Health Agency for Northern Ireland; by a Health Research Award (HRA_POR-2010-131) from the Health Research Board (HRB), Dublin; and with contribution from the HSC Research and Development Division, Public Health Agency for Northern Ireland, the Intensive Care Society of Ireland, and REVIVE. It contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

References

- 1.Zimmerman J.E., Kramer A.A., Knaus W.A. Changes in hospital mortality for United States intensive care unit admissions from 1988 to 2012. Crit Care. 2013;17:R81. doi: 10.1186/cc12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkman S., Bakhshi-Raiez F., Abu-Hanna A., de Jonge E., de Keizer N.F. Determinants of mortality after hospital discharge in ICU patients: literature review and Dutch cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1237–1251. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca4f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolan J.P., Ferrando P., Soar J. Increasing survival after admission to UK critical care units following cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care. 2016;20:219. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwashyma T. Survivorship will be the defining challenge of critical care in the 21st century. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:204–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wunsch H., Angus D.C., Harrison D.A. Variation in critical care services across North America and western Europe. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2787–2793. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186aec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS Digital . 2016. Hospital adult critical care activity 2015–16.https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB23426 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Needham D.M., Davidson J., Cohen H. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EuroQoL. EQ-5D. https://euroqol.org/(accessed 22 October 2018).

- 9.Granja C., Teixeira-Pinto A., Costa-Pereira A. Quality of life after intensive care—evaluation with EQ-5D questionnaire. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:898–907. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaarlola A., Pettilä V., Kekki P. Quality of life six years after intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1294–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowdy D.W., Eid M.P., Sedrakyan A. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oeyen S.G., Vandijck D.M., Benoit D.D., Annemans L., Decruyenaere J.M. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2386–2400. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3dec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuthbertson B.H., Roughton S., Jenkinson D., Maclennan G., Vale L. Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R6. doi: 10.1186/cc8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Timmers T.K., Verhofstad M.H.J., Moons K.G.M., van Beeck E.F., Leenen L.P.H. Long-term quality of life after surgical intensive care admission. Arch Surg. 2011;146:412–418. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orwelius L., Fredrikson M., Kristenson M., Walther S., Sjöberg F. Health-related quality of life scores after intensive care are almost equal to those of the normal population: a multicenter observational study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R236. doi: 10.1186/cc13059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soliman I.W., de Lange D.W., Peelen L.M. Single-center large-cohort study into quality of life in Dutch intensive care unit subgroups, 1 year after admission, using EuroQoL EQ-6D-3L. J Crit Care. 2015;30:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffith D.M., Salisbury L.G., Lee R.J., Lone N., Merriweather J.L., Walsh T.S. Determinants of health-related quality of life after ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerth A.M.J., Hatch R.A., Young J.D., Watkinson P.J. Changes in health-related quality of life after discharge from an intensive care unit: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2019;74:100–108. doi: 10.1111/anae.14444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware J.J., Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle M., Murgo M., Adamson H., Gill J., Elliott D., Crawford M. The effect of chronic pain on health related quality of life amongst intensive care survivors. Aust Crit Care. 2004;17:104–113. doi: 10.1016/s1036-7314(04)80012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marx G., Zimmer A., Rothaug J., Mescha S., Reinhart K., Meissner W. Chronic pain after surviving sepsis. Crit Care. 2006;10:P421. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battle C.E., Lovett S., Hutchings H. Chronic pain in survivors of critical illness: a retrospective analysis of incidence and risk factors. Crit Care. 2013;17:R101. doi: 10.1186/cc12746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choinière M., Watt-Watson J., Victor J.C. Prevalence of and risk factors for persistent postoperative nonanginal pain after cardiac surgery: a 2-year prospective multicentre study. CMAJ. 2014;186:E213–E223. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baumbach P., Götz T., Günther A., Weiss T., Meissner W. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic intensive care-related pain: the role of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1129–1137. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayhurst C.J., Jackson J.C., Archer K.R., Thompson J.L., Chandrasekhar R., Hughes C.G. Pain and its long-term interference of daily life after critical illness. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:690–697. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langerud A.K., Rustøen T., Småstuen M.C., Kongsgaard U., Stubhaug A. Health-related quality of life in intensive care survivors: associations with social support, comorbidity, and pain interference. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Association for the Study of Pain . 2012. IASP taxonomy.https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698&navItemNumber=576 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofhuis J.G.M., Spronk P.E., van Stel H.F., Schrijvers G.J.P., Rommes J.H., Bakker J. The impact of critical illness on perceived health-related quality of life during ICU treatment, hospital stay, and after hospital discharge: a long-term follow-up study. Chest. 2008;133:377–385. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korošec Jagodič H., Jagodič K., Podbregar M. Long-term outcome and quality of life of patients treated in surgical intensive care: a comparison between sepsis and trauma. Crit Care. 2006;10:1–7. doi: 10.1186/cc5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orwelius L., Nordlund A., Edéll-Gustafsson U. Role of preexisting disease in patients’ perceptions of health-related quality of life after intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1557–1564. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000168208.32006.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenewein J., Moergeli H., Wittmann L., Büchi S., Kraemer B., Schnyder U. Development of chronic pain following severe accidental injury. Results of a 3-year follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi J., Hoffman L.A., Schulz R. Self-reported physical symptoms in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors: pilot exploration over four months post ICU discharge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gifford J.M., Husain N., Dinglas V.D., Colantuoni E., Needham D.M. Baseline quality of life before intensive care: a comparison of patient versus proxy responses. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:855–860. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cd10c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinglas V., Gifford J., Husain N., Colantuoni E., Needham D.M. Quality of life before intensive care using EQ-5D: patient versus proxy responses. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:9–14. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318265f340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fayaz A., Croft P., Langford R.M., Donaldson L.J., Jones G.T. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Major M.E., Kwakman R., Kho M.E. Surviving critical illness: what is next? An expert consensus statement on physical rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Crit Care. 2016;20:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1508-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Needham D.M., Sepulveda K.A., Dinglas V.D. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bendinger T., Plunkett N. Measurement in pain medicine. BJA Educ. 2016;16:310–315. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleeland C., Ryan K. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagel B., Gerbershagen H.U., Lindena G., Pfingsten M. Entwicklung und empirische überprüfung des Deutschen schmerzfragebogens der DGSS. Schmerz. 2002;16:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00482-002-0162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicholas M. The self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dworkin R.H., Turk D.C., Farrar J.T. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Von Korff M., Ormel J., Keefe F.J., Dworkin S.F. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith B., Penny K., Purves A. The chronic pain grade questionnaire: validation and reliability in postal research. Pain. 1997;71:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)03347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Granja C., Dias C., Costa-Pereira A., Sarmento A. Quality of life of survivors from severe sepsis and septic shock may be similar to that of others who survive critical illness. Crit Care. 2004;8:R91–R98. doi: 10.1186/cc2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herridge M., Tansey C., Matte A. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dowdy D.W., Eid M.P., Dennison C.R. Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1115–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearse R.M., Harrison D.A., MacDonald N. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. JAMA. 2014;311:2181–2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harvey S.E., Parrott F., Harrison D.A. A multicentre, randomised controlled trial comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early nutritional support via the parenteral versus the enteral route in critically ill patients (CALORIES) Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2016;20:1–143. doi: 10.3310/hta20280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mouncey P.R., Osborn T.M., Power G.S. Protocolised Management In Sepsis (ProMISe):A multicentre randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early, goal-directed, protocolised resuscitation for emerging septic shock. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2015;19:1–150. doi: 10.3310/hta19970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harrison D.A., Prabhu G., Grieve R. Risk Adjustment In Neurocritical care (RAIN) – prospective validation of risk prediction models for adult patients with acute traumatic brain injury to use to evaluate the optimum location and comparative costs of neurocritical care: a cohort study. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2013;17 doi: 10.3310/hta17230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wildman M.J., Sanderson C.F.B., Groves J. Survival and quality of life for patients with COPD or asthma admitted to intensive care in a UK multicentre cohort: the COPD and Asthma Outcome Study (CAOS) Thorax. 2009;64:128–132. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.091249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griffiths J., Hatch R.A., Bishop J. An exploration of social and economic outcome and associated health-related quality of life after critical illness in general intensive care unit survivors: a 12-month follow-up study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R100. doi: 10.1186/cc12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji C., Lall R., Quinn T. Post-admission outcomes of participants in the PARAMEDIC trial: a cluster randomised trial of mechanical or manual chest compressions. Resuscitation. 2017;118:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lall R., Hamilto N.P., Young D. A randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation against conventional artificial ventilation for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Oscar (Oscillation in ARDS) study. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2015;19:1–154. doi: 10.3310/hta19230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perkins G.D., Mistry D., Gates S. Effect of protocolized weaning with early extubation to noninvasive ventilation vs invasive weaning on time to liberation from mechanical ventilation among patients with respiratory failure. JAMA. 2018;320:1881–1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Page V.J., Casarin A., Ely E.W. Evaluation of early administration of simvastatin in the prevention and treatment of delirium in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation (MoDUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:727–737. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pattison N., O’Gara G., Lucas C., Gull K., Thomas K., Dolan S. Filling the gaps: a mixed-methods study exploring the use of patient diaries in the critical care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;51:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pattison N., O’Gara G., Rattray J. After critical care: patient support after critical care. A mixed method longitudinal study using email interviews and questionnaires. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2015;31:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Page V., Ely E., Gates S. Effect of intravenous haloperidol on the duration of delirium and coma in critically ill patients (hope-ICU) Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:515–523. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70166-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Batterham A.M., Bonner S., Wright J., Howell S.J., Hugill K., Danjoux G. Effect of supervised aerobic exercise rehabilitation on physical fitness and quality-of-life in survivors of critical illness: an exploratory minimized controlled trial (PIX study) Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:130–137. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McAuley D.F., Laffey J., O’Kane C. Simvastatin in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. 2NEJM. 2014;371:1695–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hatch R., Young D., Barber V., Harrison D.A., Watkinson P. The effect of postal questionnaire burden on response rate and answer patterns following admission to intensive care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wright S.E., Thomas K., Watson G. Intensive versus standard physical rehabilitation therapy in the critically ill (EPICC): a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2018;73:213–221. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kosek E., Cohen M., Baron R. Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states. Pain. 2016;157:1382–1386. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kyranou M., Puntillo K. The transition from acute to chronic pain: might intensive care unit patients be at risk? Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2:36. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Puntillo K.A., Max A., Chaize M., Chanques G., Azoulay E. Patient recollection of ICU procedural pain and post ICU burden: the memory study. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1988–1995. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kemp H.I., Bantel C., Gordon F. Pain assessment in INTensive Care (PAINT): an observational study of physician-documented pain assessment in 45 intensive care units in the United Kingdom. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:737–748. doi: 10.1111/anae.13786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Devlin J.W., Skrobik Y., Gélinas C. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e825–e873. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Badcock L.J., Lewis M., Hay E.M., McCarney R., Croft P.R. Chronic shoulder pain in the community: a syndrome of disability or distress? Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:128–131. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Witt N.J., Zochodne D.W., Bolton C.F. Peripheral nerve function in sepsis and multiple organ failure. Chest. 1991;99:176–184. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stevens R.D., Dowdy D.W., Michaels R.K., Mendez-Tellez P.A., Pronovost P.J., Needham D.M. Neuromuscular dysfunction acquired in critical illness: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1876–1891. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marchand F., Perretti M., McMahon S.B. Role of the immune system in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:521–532. doi: 10.1038/nrn1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fan E., Dowdy D.W., Colantuoni E. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a two-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:849–859. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clavet H., Hebert P.C., Fergusson D., Doucette S., Trudel G. Joint contracture following prolonged stay in the intensive care unit. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178:691–697. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Latronico N., Shehu I., Seghelini E. Neuromuscular sequelae of critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:381–390. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000168530.30702.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Misak C.J. ICU-acquired weakness: obstacles and interventions for rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:845–846. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1110OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Angel M.J., Bril V., Shannon P., Herridge M.S. Neuromuscular function in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34:427–432. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100007307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fletcher S.N., Kennedy D.D., Ghosh I.R. Persistent neuromuscular and neurophysiologic abnormalities in long-term survivors of prolonged critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1012–1016. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000053651.38421.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Semmler A., Okulla T., Kaiser M., Seifert B., Heneka M.T. Long-term neuromuscular sequelae of critical illness. J Neurol. 2013;260:151–157. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Latronico N., Filosto M., Fagoni N. Small nerve fiber pathology in critical illness. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Skorna M., Kopacik R., Vlckova E., Adamova B., Kostalova M., Bednarik J. Small-nerve-fiber pathology in critical illness documented by serial skin biopsies. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52:28–33. doi: 10.1002/mus.24489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Axer H., Grimm A., Pausch C. The impairment of small nerve fibers in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care. 2016;20:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1241-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Timar B., Popescu S., Timar R., Baderca F., Duica B., Vlad M. The usefulness of quantifying intraepidermal nerve fibers density in the diagnostic of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a cross-sectional study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2016;8:31. doi: 10.1186/s13098-016-0146-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maier C., Baron R., Tölle T.R. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): somatosensory abnormalities in 1236 patients with different neuropathic pain syndromes. Pain. 2010;150:439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Finnerup N.B., Haroutounian S., Kamerman P. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016;157:1599–1606. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Backonja M.M., Attal N., Baron R. Value of quantitative sensory testing in neurological and pain disorders: NeuPSIG consensus. Pain. 2013;154:1807–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baumbach P., Götz T., Günther A., Weiss T., Meissner W. Somatosensory functions in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e567–e574. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coggon D., Ntani G., Palmer K.T. Patterns of multisite pain and associations with risk factors. Pain. 2013;154:1769–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carnes D., Parsons S., Ashby D. Chronic musculoskeletal pain rarely presents in a single body site: results from a UK population study. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1168–1170. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Von Korff M., Crane P., Lane M. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain. 2005;113:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Orwelius L., Nordlund A., Nordlund P. Pre-existing disease: the most important factor for health related quality of life long-term after critical illness: a prospective, longitudinal, multicentre trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R67. doi: 10.1186/cc8967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Demyttenaere K., Bruffaerts R., Lee S. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: results from the world mental health surveys. Pain. 2007;129:332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fishbain D.A., Pulikal A., Lewis J.E., Gao J. Chronic pain types differ in their reported prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and there is consistent evidence that chronic pain is associated with PTSD: an evidence-based structured systematic review. Pain Med. 2016;18:711–735. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moriarty O., McGuire B.E., Finn D.P. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:385–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gjeilo K.H., Klepstad P., Wahba A., Lydersen S., Stenseth R. Chronic pain after cardiac surgery: a prospective study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bruce J., Quinlan J. Chronic post surgical pain. Rev Pain. 2011;5:23–29. doi: 10.1177/204946371100500306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Raebel M., Newcomer S., Bayliss E. Chronic opioid use emerging after bariatric surgery. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:1247–1257. doi: 10.1002/pds.3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yaffe P.B., Green R.S., Butler M.B., Witter T. Is admission to the intensive care unit associated with chronic opioid use? A 4-year follow-up of intensive care unit survivors. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;32:429–435. doi: 10.1177/0885066615618189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang H.T., Hill A.D., Gomes T. Opioid use after ICU admission among elderly chronic opioid users in Ontario. Crit Care Med. 2018:1934–1942. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pavoni V., Gianesello L., Paparella L., Buoninsegni L., Barboni E. Outcome predictors and quality of life of severe burn patients admitted to intensive care unit. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:24. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-18-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Correll D. Chronic postoperative pain: recent findings in understanding and management. F1000Res. 2017;6:1054. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11101.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guimarães-Pereira L., Reis P., Abelha F., Azevedo L.F., Castro-Lopes J.M. Persistent postoperative pain after cardiac surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis regarding incidence and pain intensity. Pain. 2017;158:1869–1885. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.van der Schaaf M., Beelen A., Dongelmans D.A., Vroom M.B., Nollet F. Poor functional recovery after a critical illness: a longitudinal study. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:1041–1048. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Connolly B., O’Neill B., Salisbury L. Physical rehabilitation interventions for adult patients with critical illness across the continuum of recovery: an overview of systematic reviews protocol. Syst Rev. 2015;4:881–890. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0119-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Walsh T.S., Salisbury L.G., Merriweather J.L. Increased hospital-based physical rehabilitation and information provision after intensive care unit discharge: the RECOVER randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:901–910. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Connolly B., Douiri A., Steier J., Moxham J., Denehy L., Hart N. A UK survey of rehabilitation following critical illness: implementation of NICE Clinical Guidance 83 (CG83) following hospital discharge. BMJ Open. 2014;4:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Rehabilitation after critical illness in adults. 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg83 [PubMed]

- 109.Chanques G., Jaber S., Barbotte E. Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1691–1699. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218416.62457.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hoc A.P., Payen J.-F., Bosson J.-L. Pain assessment is associated with decreased duration of mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: a post hoc analysis of the DOLOREA study. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1308–1316. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c0d4f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kastrup M., von Dossow V., Seeling M. Key performance indicators in intensive care medicine. A retrospective matched cohort study. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1267–1284. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Skrobik Y., Ahern S., Leblanc M., Marquis F., Awissi D.K., Kavanagh B.P. Protocolized intensive care unit management of analgesia, sedation, and delirium improves analgesia and subsyndromal delirium rates. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:451–463. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d7e1b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Payen J.F., Chanques G., Mantz J. Current practices in sedation and analgesia for mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a prospective multicenter patient-based study. Anaesthesiology. 2007;106:687–695. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264747.09017.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Luetz A., Balzer F., Radtke F.M. Delirium, sedation and analgesia in the intensive care unit: a multinational, two-part survey among intensivists. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.van der Woude M.C.E., Bormans L., Hofhuis J.G.M., Spronk P.E. Current use of pain scores in Dutch intensive care units: a postal survey in The Netherlands. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:456–461. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gustafson O.D., Rowland M.J., Waykinson P.J., McKechnie S., Igo S. Shoulder impairment following critical illness: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1769–1774. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]