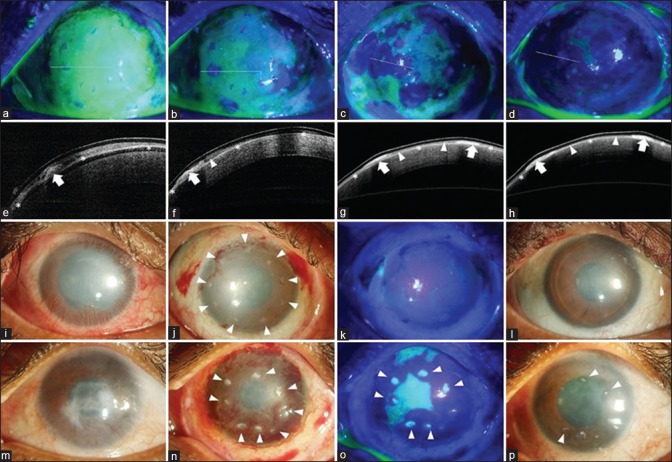

Figure 3.

Mechanism of corneal healing after simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET). The top row shows cobalt blue–illuminated fluorescein-stained images of the ocular surface immediately after SLET (a to d) with corresponding anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) images in the second row (e to h). On postoperative day (POD) 1, the cornea is covered with fibrin glue with the epithelium-up limbal transplant pieces visible as tiny islands of negative staining (a); the white line denotes the location of the AS-OCT section which in the corresponding image below shows the hyperreflective limbal piece (bold white arrow, e) while the white asterisks denote the high-reflective human amniotic membrane graft. On POD 5, areas of negative staining denoting epithelial outgrowth are seen around several of the individual transplants (b); which corresponds to the hyporeflective mass (white arrowhead) extending from the edge of the transplant (bold white arrow, f). Subsequent images on POD 7 and 10 show coalescing of the neighboring epithelial sheets to form a stratified epithelial sheet (c and g; d and h). The third row shows the typical postoperative course in a case of total limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD, i) when the transplants are correctly oriented epithelial side up (white arrowheads, j); complete epithelization is usually seen by POD 14 (k) and the transplants are barely visible at 3 months with significant reduction in surface inflammation and improvement in corneal clarity (l) as compared to baseline (i). In a similar case of total LSCD (m), where the transplants were inadvertently placed with the epithelial side down (white arrowheads, n), epithelial healing is delayed at POD 14 and each individual transplant stains positively with fluorescein dye (o) and the stromal side of the transplants are still visible at 3 months as white opacities (white arrowheads, p)