CONSPECTUS

Transition-metal catalysis has revolutionized the field of organic synthesis by facilitating the construction of complex organic molecules in a highly efficient manner. Although these catalysts are typically based on precious metals, researchers have made great strides in discovering new base metal catalysts over the past decade.

This Account describes our efforts in this area and details the development of versatile Ni complexes that catalyze a variety of cycloaddition reactions to afford interesting carbocycles and heterocycles. First, we describe our early work in investigating the efficacy of N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands in Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions with carbon dioxide and isocyanate. The use of sterically hindered, electron donating NHC ligands in these reactions significantly improved the substrate scope as well as reaction conditions in the syntheses of a variety of pyrones and pyridones. The high reactivity and versatility of these unique Ni(NHC) catalytic systems allowed us to develop unprecedented Ni-catalyzed cycloadditions that were unexplored due to the inefficacy of early Ni catalysts to promote hetero-oxidative coupling steps. We describe the development and mechanistic analysis of Ni/NHC catalysts that couple diynes and nitriles to form pyridines. Kinetic studies and stoichiometric reactions confirmed a hetero-oxidative coupling pathway associated with this Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition. We then describe a series of new substrates for Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions such as vinylcyclopropanes, aldehydes, ketones, tropones, 3-azetidinones, and 3-oxetanones. In reactions with vinycyclopropanes and tropones, DFT calculations reveal noteworthy mechanistic steps such as a C–C σ-bond activation and an 8π-insertion of vinylcyclopropane and tropone, respectively. Similarly, the cycloaddition of 3-azetidinones and 3-oxetanones also requires Ni-catalyzed C–C σ-bond activation to form N- and O-containing heterocycles.

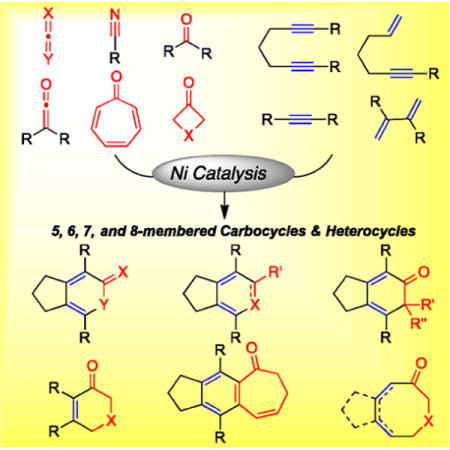

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

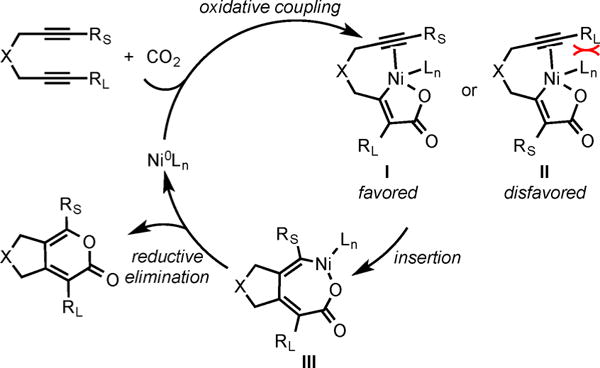

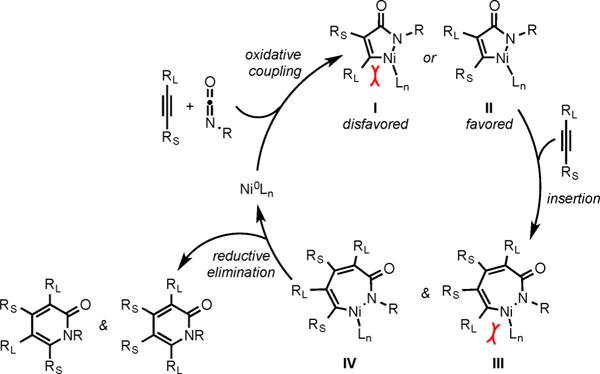

A primary interest of our research group is to develop Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions to construct a variety of carbocycles and heterocycles in an efficient manner. Prior to our work in 2002, a handful of Ni-phosphine complexes were known in literature to catalyze the cycloaddition of heterocumulenes, such as CO2 and isocyanates, with alkynes to form heterocyclic compounds.1 However, almost all of these systems required harsh reaction conditions for their success thereby reducing their synthetic utility. These limitations prompted us to investigate new catalytic systems to make these existing methodologies more efficient. In this context, we speculated that the sterically bulky and electron-rich NHC ligands (NHC = N-heterocyclic carbene) could enhance catalytic activity. First, Ni/phosphine-catalyzed reactions were believed to occur through initial oxidative coupling between the alkyne and the heterocumulene (hetero-oxidative coupling) rather than between two alkynes (homo-oxidative coupling). As such, we predicted the increased donacity would intensify the nucleophilicity of the Ni catalyst thereby enhancing both binding of the heterocumulene (i.e., the electrophile) and the subsequent hetero-oxidative coupling event (Scheme 1).

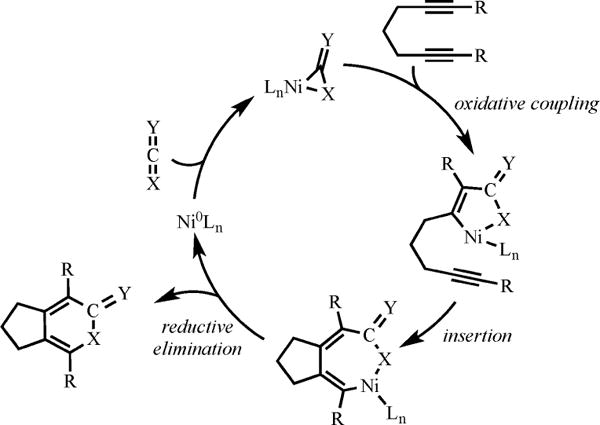

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of Ni-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diyne and Heterocumulene

Second, we suspected that the last step of the mechanism to form heterocycles was Ni-mediated C–X bond-forming reductive elimination. Analogous Pd-mediated reductive elimination reactions generally occur through a highly unsaturated Pd intermediate2 that is stabilized by electron-donating, sterically hindered ligands. Thus, these features of the NHC ligand were likely to promote the reductive elimination step in the cycloaddition reaction. Lastly, as an added benefit, the larger NHC ligands could discourage homo-oxidative coupling since two (internal) alkynes require larger binding sites than an alkyne and a heterocumulene. Indeed, our first foray into Ni/NHC-catalyzed cycloaddition, with CO2, suggested that our hypotheses were correct because these cycloaddition reactions occurred under mild conditions with high selectivity and efficiency. We quickly realized the greater potential of these interesting Ni/NHC catalytic systems in the development of new cycloaddition reactions that can incorporate challenging and unprecedented coupling partners. To date, we have applied Ni/NHC and Ni/phosphine based catalytic systems to known, as well as many new, cycloaddition substrates to afford a variety of interesting heterocycles and carbocycles.

This Account describes our group’s contribution toward the development of highly versatile Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions to synthesize carbocyclic and heterocyclic compounds.

2. Ni-CATALYZED CYCLOADDITION OF DIYNES AND CARBON DIOXIDE

Carbon dioxide being a renewable, nontoxic, and abundant resource has always attracted scientists to utilize this cheap C-1 source in forming new carbon–carbon bonds.3 However, the high thermodynamic and kinetic stability of this molecule makes its activation challenging and often requires harsh reaction conditions to facilitate these processes. In our quest to develop methods that utilize carbon dioxide as a starting material, we were drawn to Saegusa’s earlier discovery that Ni-phosphine complexes could catalyze the cycloaddition of diynes and CO2 to form pyrones.1b Unfortunately, this methodology required variable catalyst systems for different diyne substrates, high temperature, and high CO2 pressure thereby limiting the ability to effectively use carbon dioxide as a starting material. We speculated that the replacement of the phosphine ligands with a sterically hindered, electron rich NHC ligand would enhance the reactivity of the Ni catalysts (vide supra). Thus, in 2002, our group successfully overcame these limitations by developing a highly efficient Ni/NHC-catalyzed cycloaddition of diynes and CO2 to form pyrones (Scheme 2).4 Importantly, our methodology uses only atmospheric pressure of CO2, relatively low catalyst loadings, and moderate reaction temperatures.

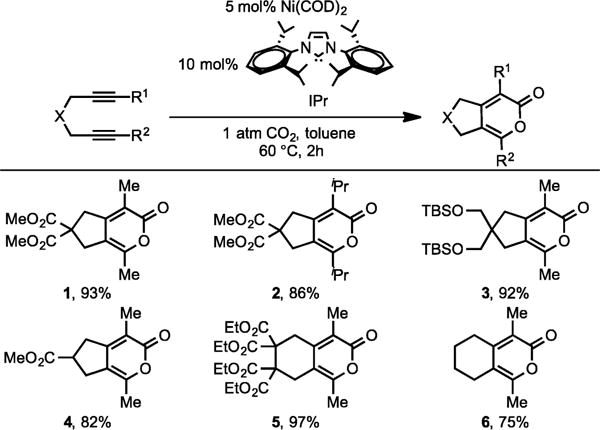

Scheme 2.

Ni/IPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Symmetrical Diynes with CO2

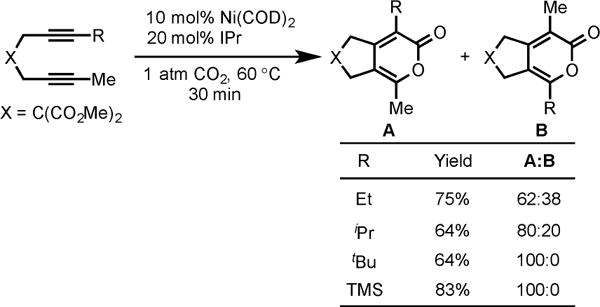

A variety of symmetrical diynes were efficiently coupled to afford pyrones in excellent yields (1–6). Regioselectivity in the cycloaddition of unsymmetrical diynes was discovered to be highly dependent on the substituents on the alkyne termini in diynes (Scheme 3).4b With the increase in the size of alkyne substituent R, the regioselectivity increased in favor of the pyrone A over B. Complete regioselectivity toward pyrone A was observed when large substituents, such as tBu and TMS-bearing unsymmetrical diynes, were employed.

Scheme 3.

Ni/IPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Unsymmetrical Diynes and CO2

Based on Hoberg’s and Burkhart’s studies on the stoichiometric reactions of Ni(0) complexes with alkynes5 and CO2 and the regioselectivity observed in our Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition of diynes and CO2 (Scheme 3), a mechanism involving the heterooxidative coupling of alkyne and CO2 seems plausible (Scheme 4). The regioselectivity appears to be dominated by minimizing the steric interactions between the alkyne substituent and the bulky IPr ligand during in alkyne insertion. That is, insertion of the coordinated alkyne bearing the smaller substituent RS is favored (intermediate I versus intermediate II) and affords intermediate III, which upon reductive elimination would form the product and regenerate the Ni(0) catalyst.

Scheme 4.

Mechanism of Ni/IPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and CO2

3. Ni-CATALYZED CYCLOADDITION OF ALKYNES AND ISOCYANATES

With the discovery that the NHC ligand increased the reactivity in Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition of alkynes with CO2, a generally nonreactive heterocumulene, we were interested in exploring whether a similar trend existed for other heterocumulenes such as isocyanates. Prior to our investigation, a similar study performed by Hoberg demonstrated that Ni/PR3 did effect the cycloaddition between alkynes and isocyanates; however, reaction temperatures were again high, and more importantly, the substrate scope was limited.1a Furthermore, existing Co and Ru catalysts also required high reaction temperatures or high catalyst loadings or both.6,7

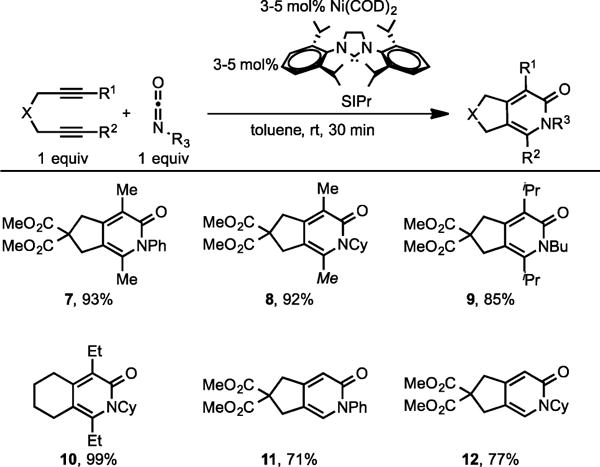

After a brief reaction optimization, we discovered that combination of catalytic amounts of Ni(COD)2 and SIPr were highly effective for the cycloaddition of diynes and isocyanates to form 2-pyridones at room temperature and under short reaction times (Scheme 5).8

Scheme 5.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Isocyanates

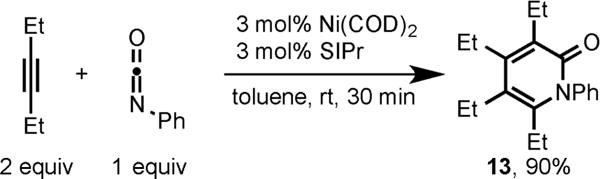

This methodology had a broad substrate scope in terms of both diynes and isocyanates (7–12). This Ni/SIPr system was also effective in catalyzing an intermolecular cycloaddition of 3-hexyne and phenyl isocyanate to form 13, in excellent yield (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of 3-Hexyne and Phenyl Isocyanate

Further investigation into three-component cycloaddition led to the discovery of a more effective Ni/PEt3 system to catalyze the cycloaddition of various unsymmetrically substituted internal alkynes with both alkyl and aryl isocyanates (Scheme 7).9 The cycloaddition of sterically biased alkynes such as 1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne with Ph- and Et-isocyanate led to a 1:1 mixture of two regioisomeric 2-pyrones, respectively. Interestingly, replacement of the methyl group in 1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne with a tBu or a propenyl group led to the regioselective formation of only cycloadduct in which the carbon bearing the bulky substituent is next to the carbonyl group (16 and 17). Similarly, the use of an aryl–alkyl alkyne such as 1-phenyl-1-propyne led to a high selectivity for the formation of cycloadduct 18 that contains the alkyl substituent next to the carbonyl group.

Scheme 7.

Ni/PEt3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Alkynes and Isocyanates

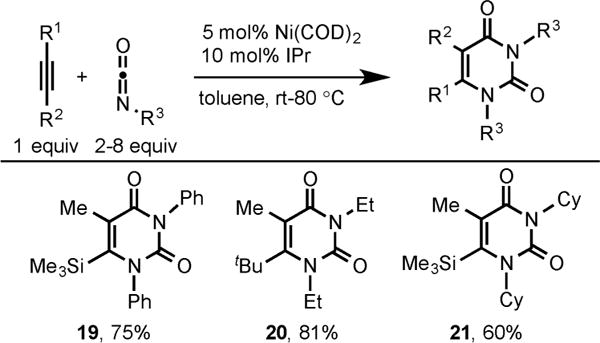

Interestingly, if excess isocyanate is used in cycloaddition with alkynes using Ni/IPr catalyst, pyrimidine-dione products are obtained instead of 2-pyrone (Scheme 8).10

Scheme 8.

Ni/IPr-Catalyzed Synthesis of Pyrimidine-Diones via Cycloaddition of Alkynes and Isocyanates

Based on early stoichiometric Ni-mediated cycloaddition reactions of alkynes and isocyanates, we believe the cycloaddition of diynes and isocyanates follows the heterocoupling mechanism analogous to the cycloaddition of diynes and CO2 (Scheme 4).5 The mechanism of intermolecular cycloaddition involves the selective initial oxidative coupling of an unsymmetrical alkyne and an isocyanate to form the favored nickellacycle II, in order to avoid the steric interactions between the bulky substituent RL on the alkyne and the ligand (Scheme 9). The insertion of another alkyne unit would also be dictated by the similar steric interactions between RL and the ligand to form III and IV, but with a less pronounced effect as shown by the formation of 1:1 mixture of regioisomeric pyridones (14 and 14′, 15 and 15′, Scheme 7).9 Finally reductive elimination from III and IV would form the observed regioisomeric products.

Scheme 9.

Proposed Mechanism for the Intermolecular Cycloaddition of Alkynes and Isocyanates To Form Pyridones

Instead, if excess isocyanate is used, the Ni/IPr catalyst is able to mediate the insertion of another isocyanate unit to form a pyrimidine-dione product through the mechanism shown in Scheme 10.10

Scheme 10.

Proposed Mechanism for the Synthesis of Pyrimidine-Diones

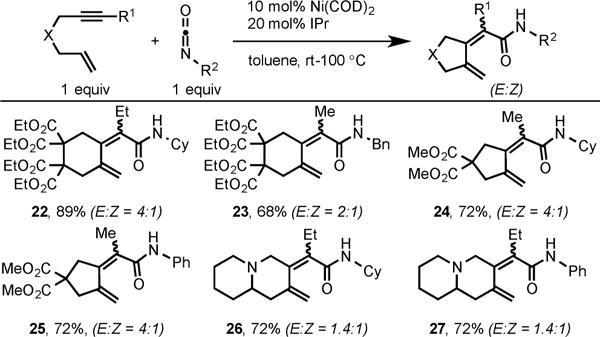

Our Ni/NHC system was also evaluated for the cycloaddition of enynes with isocyanates. Gratifyingly, the use of catalytic Ni(COD)2/IPr proved to be a general catalyst for this cycloaddition.11 A variety of enynes were coupled to both alkyl and aryl isocyanates to afford dienamides as a mixture of E/Z isomers, in high yield (Scheme 11).

Scheme 11.

Ni/IPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Enynes and Isocyanates

4. Ni-CATALYZED CYCLOADDITION OF ALKYNES AND NITRILES

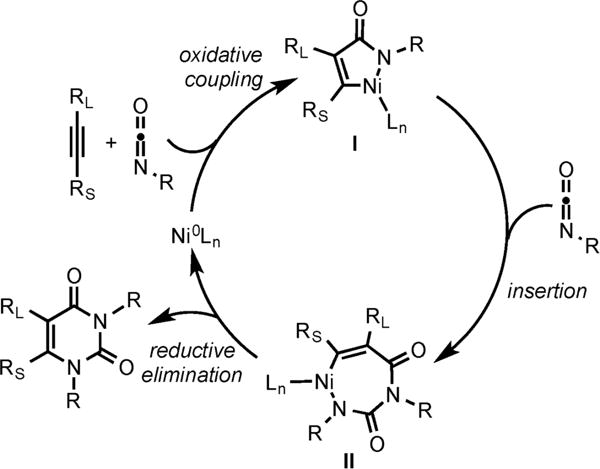

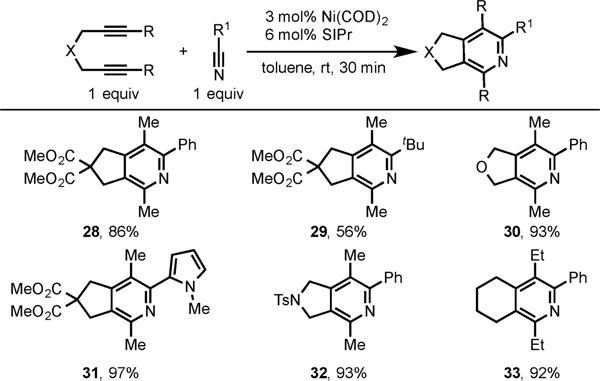

Unfortunately, the Ni-catalyzed pyridine formation via cycloaddition of alkynes and nitriles remained a longstanding challenge due to obstacles associated with the first step in cycloaddition, namely, the Ni-mediated oxidative coupling of alkynes and nitriles.12 Given our success with CO2 and isocyanate substrates, we suspected the increased nucleophilicity of the Ni/NHC system would enhance the required hetero-oxidative coupling with nitriles thereby allowing catalytic pyridine formation. In 2005, we demonstrated that the SIPr ligand with Ni(COD)2 did indeed catalyze the cycloaddition of diynes and nitriles (Scheme 12).13a A variety of diynes were coupled with alkyl, aryl, and heteroaryl nitriles to afford fused pyridines in high yields (28–33).

Scheme 12.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Nitriles

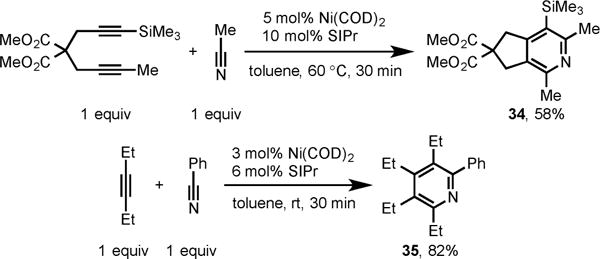

As observed with our previously reported Ni-catalyzed cycloadditions, regioselective formation of pyridine 34, where the smaller substituent ends up proximal to the N atom in the ring, was formed from acetonitrile and an unsymmetrical diyne (Scheme 13). This catalytic system also successfully promoted an intermolecular cycloaddition of 3-hexyne and benzonitrile to afford highly substituted pyridine, 35, in 82% yield.

Scheme 13.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Unsymmetrical Diyne with Acetonitrile and 3-Hexyne with Benzonitrile

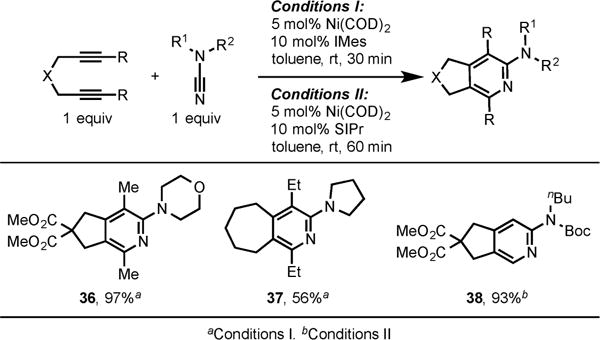

We later extended this chemistry toward the use of cyanamides to form 2-aminopyridines.13b We discovered that cyanamides were more reactive than simple nitriles and that a Ni(COD)2/IMes system is highly efficient in catalyzing the cycloaddition of internal diynes and cyanamides. Additionally, by change of the ligand from IMes to SIPr, terminal diynes were also incorporated in this cycloaddition (Scheme 14).

Scheme 14.

Ni/IMes- and Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Cyanamides

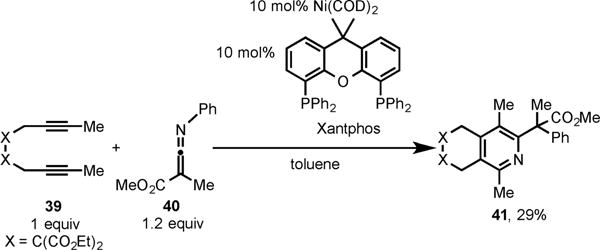

With the successful incorporation of nitriles in Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition, we were interested in using ketenimines in cycloaddition with diynes. Surprisingly, our initial investigation using the catalytic Ni(COD)2/Xantphos system for the cycloaddition of diyne 39 and ketenimine 40 revealed the formation of pyridine 41, albeit in low yield (Scheme 15).13c

Scheme 15.

Ni/Xantphos-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diyne 39 and Ketenimine 40

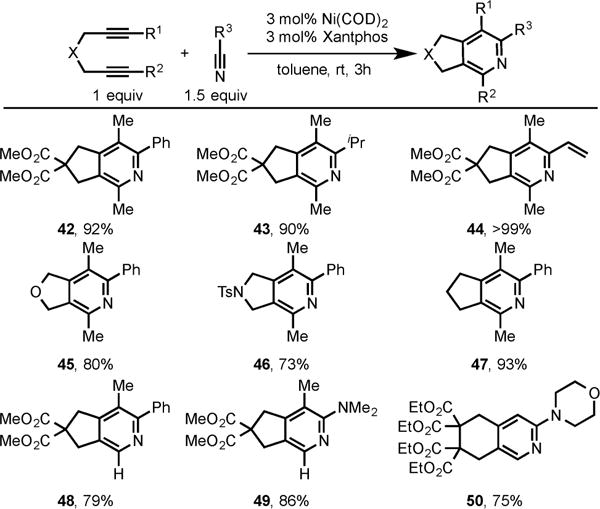

This intriguing result prompted us to investigate the Ni/Xantphos system for the cycloaddition of diynes and nitriles. To our delight, this catalytic system was not only discovered to be a general catalyst for the synthesis of pyridines but also superior to other known Ru, Co, Rh, and Fe, as well as our own Ni/SIPr, catalytic systems. This result is contrary to our previous hypothesis that the highly electron-rich NHC ligand is required for the Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition of diynes and nitriles, since Xantphos is an electron-deficient bidentate phosphine ligand.13c This Ni/Xantphos system offers a broad substrate scope in terms of both diynes and nitriles (Scheme 16).

Scheme 16.

Ni/Xantphos-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes with Nitriles and Cyanamides

The use of unsymmetrical diyne led to regioselective cycloadducts 48 and 49, with both nitrile and cyanamide, respectively, in high yields. This methodology also effectively couples terminal diyne as demonstrated by the formation of pyridine 50.

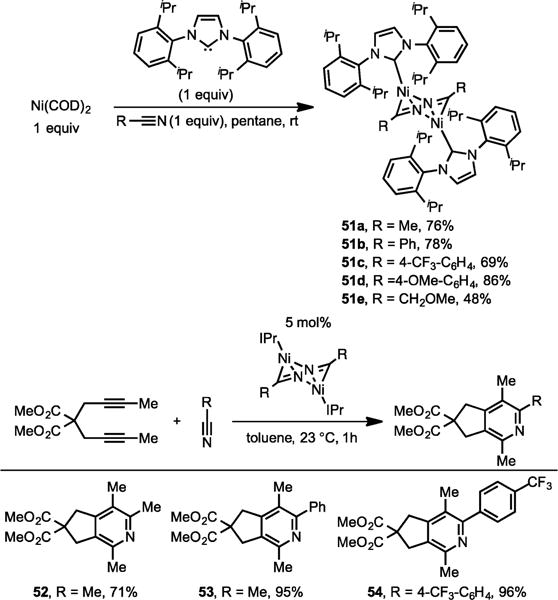

Given the remarkable aptitude of the Ni/IPr system toward nitrile cycloaddition (presumably due to improved Ni-mediated oxidative coupling of alkynes and nitriles), we embarked in a detailed mechanistic analysis of the reaction. Our initial investigations lead to the discovery of an interesting dimeric [Ni(IPr)RCN]2 species (Scheme 17, 51a–e) that can also catalyze the cycloaddition of diynes and nitriles (Scheme 17, 52–54).13d

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of [Ni(IPr)RCN]2 and Their Catalytic Activity for the Cycloaddition of Diynes and Nitriles

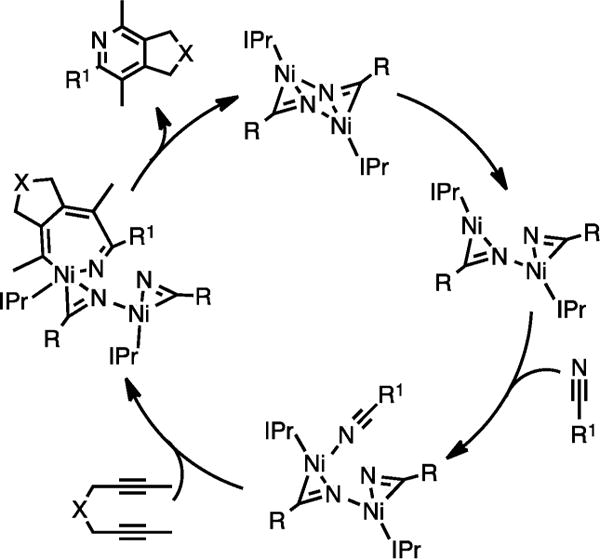

Further experiments, which included stoichiometric cycloaddition reactions, ligand exchange experiments, and kinetic analyses with these nitrile-bound Ni(IPr)-dimeric species, suggested the mechanism shown in Scheme 18.13d The [Ni(IPr)RCN]2 species I undergoes a unique rate-limiting partial dimer opening to form intermediate II, which binds to the nitrile R1–CN to form III. Subsequent oxidative coupling and insertion of diyne on Ni in III leads to intermediate IV that would eventually reductively eliminate to afford the pyridine product and regenerate the Ni-dimeric species I.

Scheme 18.

Proposed Mechanism for the [Ni(IPr)RCN]2-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Nitriles

Further investigation revealed that in our quest to understand the mechanism of Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition of alkynes and nitriles, we actually had discovered a completely distinct catalyst system. That is, comparison of the rate data revealed that although [Ni(IPr)RCN]2 was catalytically competent, it was not kinetically competent compared with the parent Ni(IPr)2 system.

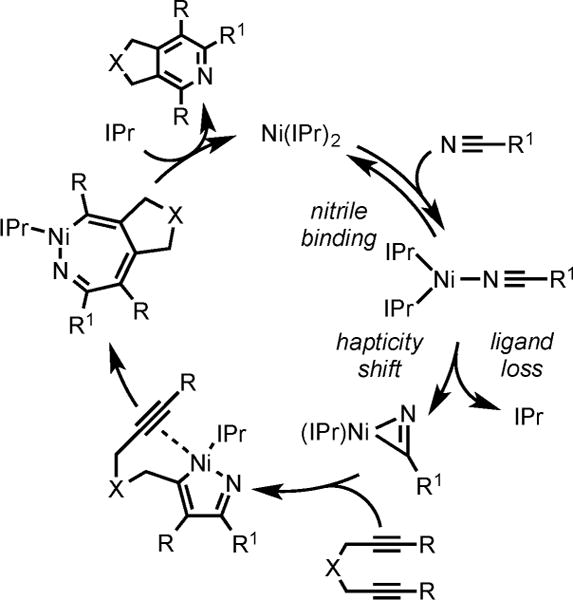

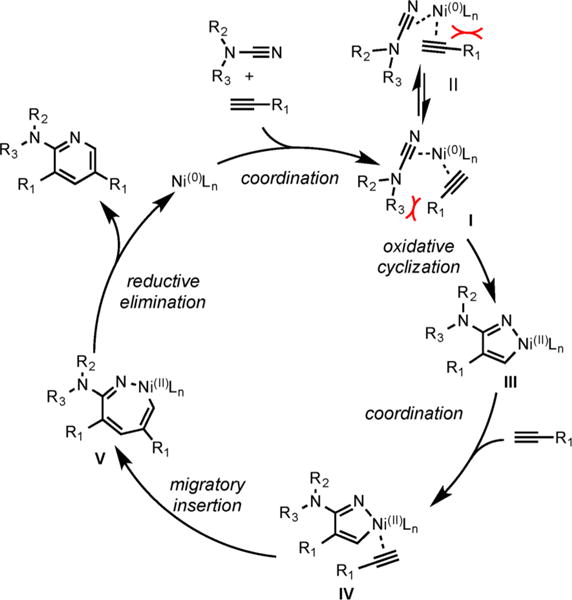

Nevertheless, a complete mechanistic profiling of the Ni(IPr)2 system confirmed that, like the [Ni(IPr)RCN]2 catalyst, pyridine formation arose from initial hetero-oxidative coupling between an alkyne and a nitrile rather than homo-oxidative coupling between two alkynes (Scheme 19).13e Key evidence to support the involvement of a heterocoupling mechanism in the Ni(NHC)2-catalytic system included in situ stoichiometric transmetalation reactions between zirconacycles and Ni(IPr)(acac)2 [acac = acteylactetonate], the observed regiochemistry in the cycloaddition of unsymmetrical diynes and nitriles, and kinetic analyses. Our kinetic analyses also revealed that nitrile binding occurs through an associative ligand substitution pathway. Thus, reversible binding of the nitrile to Ni(IPr)2 forms intermediate I, which would undergo ligand loss with subsequent hapticity shift to form II. Hetero-oxidative coupling with one alkyne of diyne and η2-bound nitrile in II leads to intermediate III, which undergoes insertion of the pendant alkyne to form the Ni-azacycloheptatriene intermediate IV. Finally reductive elimination from IV and subsequent IPr coordination affords the pyridine product and regenerates the Ni(IPr)2 catalyst.

Scheme 19.

Proposed Mechanism for the Ni(IPr)2-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Nitriles

To extend this chemistry toward the potential regioselective synthesis of monocyclic pyridines, we recently developed a Ni/SIPr catalyzed intermolecular cycloaddition of terminal alkynes and cyanamides (Scheme 20).13f Cycloaddition afforded a mixture of 3,5-disubstituted and 4,6-disubstituted 2-amino-pyrdines as major and minor isomers, respectively, in low to good yields. The moderate yields observed in this methodology are due to the side reaction involving the oligomerization of alkynes.

Scheme 20.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Terminal Alkynes and Cycnamides

We believe that a mechanism involving hetero-oxidative coupling between a nitrile and an alkyne is still operative and that formation of I is favored over II, which dictates the observed regioselectivity (Scheme 21).

Scheme 21.

Proposed Mechanism for the Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Terminal Alkynes and Cycnamides

5. Ni-CATALYZED CYCLOADDITION OF ALKYNES/ALKENES WITH ALDEHYDES AND KETONES

Another early challenge for us in developing versatile Ni catalysis was to incorporate carbonyl substrates such as aldehydes and ketones. Despite numerous reports on the transition-metal-catalyzed cycloaddition, the use of aldehydes and ketones was largely unexplored due to their increased steric hindrance and a challenging C–O bond reductive elimination step that would be required for product formation. Only two examples, which were based on Ni and Ru systems, were known to couple diynes with carbonyl compounds at the time.14 However, they were limited to the use of activated carbonyl compounds, high reaction temperatures, or high catalyst loadings.

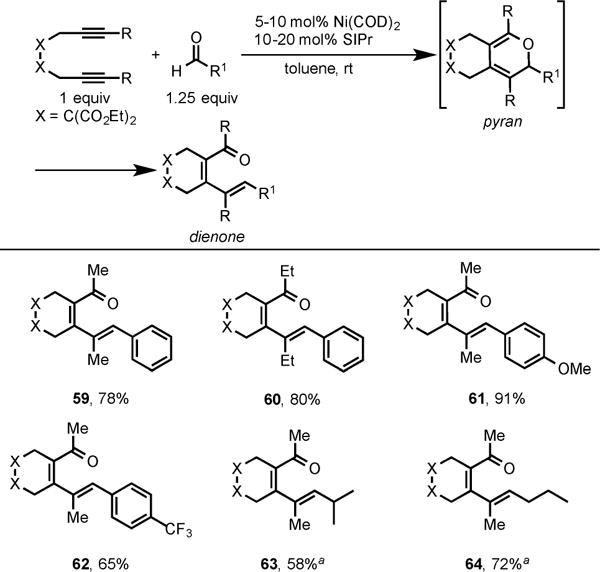

After screening a variety of phosphine and carbene ligands, we again discovered that our Ni/SIPr could indeed catalyze the cycloaddition of diynes and aldehydes at room temperature to afford dienones (Scheme 22).15a Activated aldehydes such as benzaldehyde, p-methoxy benzaldehyde, and p-CF3-benzaldehyde afforded dienones 60, 61, and 62, respectively, in high yields. Unactivated aldehydes were also tolerated in this cycloaddition using modified conditions (10 mol % Ni(COD)2 and 10 mol % SIPr) to afford an equilibrium mixture of pyran (minor) and dienone (major) isomers (63 and 64).

Scheme 22. Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Aldehydes.

aProduct was obtained as an equilibrium mixture of dienone (major) and pyran (minor).

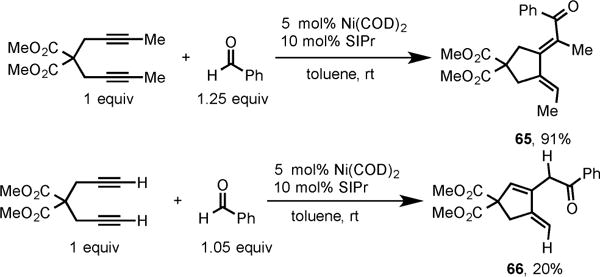

Interestingly, the use of internal 2,7-diyne and terminal 1,6-diyne in this cycloaddition led to dienones (65 and 66) with different substitution pattern than those obtained with 2,8-diynes (Scheme 23).15a The dienones 65 and 66 have the phenyl group of benzaldehyde attached to the carbonyl carbon in the product, whereas the corresponding bond of benzaldehyde is cleaved in the dienones obtained from 2,8-diynes (59–64).

Scheme 23.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Internal 2,7-Diyne and Terminal 1,6-Diyne with Benzaldehyde

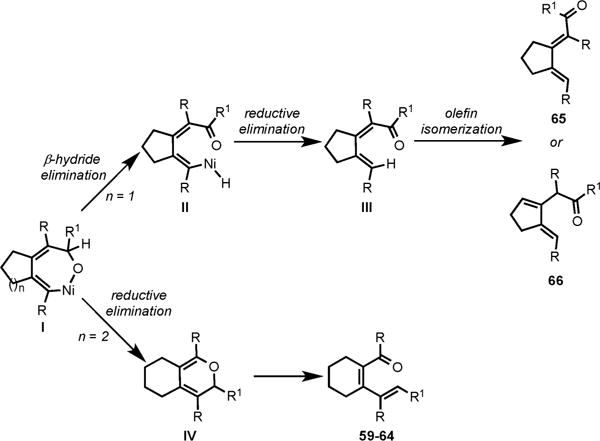

To explain the formation of these different products, we proposed that depending upon the nature of diyne used, a common nickellacycle I could undergo either β-hydride elimination or reductive elimination to afford these varied dienones (Scheme 24). In the cycloaddition of 2,7-diyne and 1,6-diyne, β-hydride elimination from I would afford the Nihydride species II that on reductive elimination would lead to dienone III. This dienone could undergo olefin isomerization to afford the observed cycloadducts (65 and 66). The preferential β-hydride elimination over reductive elimination in this case would be due to the higher energy barrier associated with the reductive elimination to form a relatively strained [5,6]-fused ring system. In case of 2,8-diynes, selective reductive elimination would afford the less strained [6,6]-fused pyran IV, which would undergo electrocyclic ring opening to yield the observed dienones (59–64).

Scheme 24.

Proposed Mechanism for the Formation of Diverse Dienones

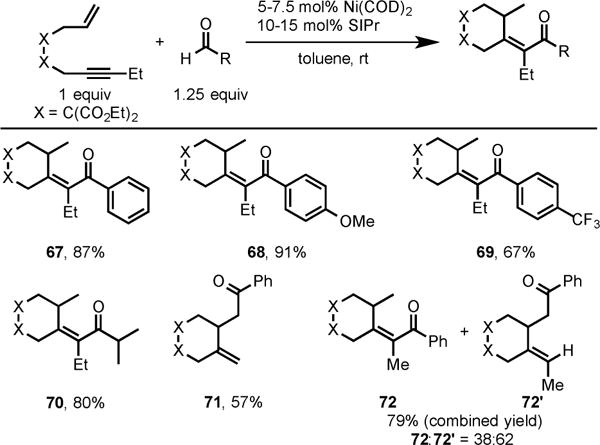

We also extended this chemistry to cycloaddition of enynes and aldehydes. Our Ni/SIPr catalytic system was highly effective in coupling a variety of enynes with both activated and unactivated aldehydes to form enones arising from the addition of aldehyde to the alkyne (Scheme 25).15b

Scheme 25.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Enynes and Aldehydes

Interestingly, the use of terminal enyne afforded ketone 71, whereas enyne bearing a methyl group at alkyne terminus led to a mixture of ketone 72 and enone 72′, respectively in high yield (Scheme 25).

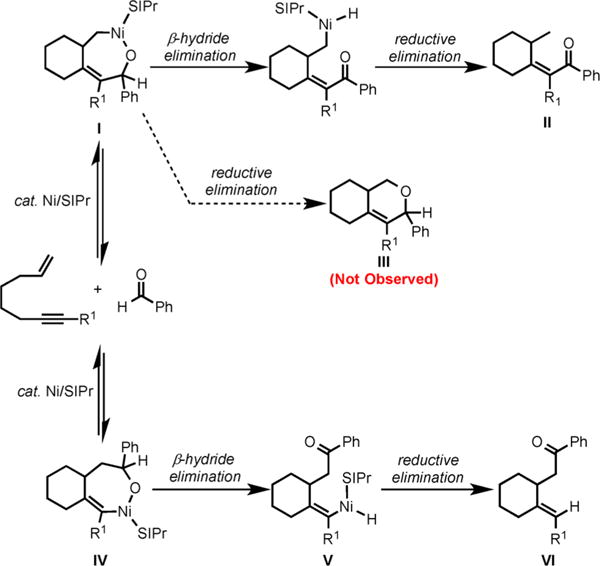

Our mechanistic proposal for the Ni/SIPr-catalyzed cycloaddition of enynes and aldehydes is shown in Scheme 26. With the increase in steric bulk of the alkynyl substituent R1, the coupling of alkyne and aldehyde via nickellacycle I would be favored to avoid steric hindrance between R1 and SIPr ligand. Subsequent β-hydride elimination and reductive elimination would afford the enone product II (Scheme 25). However, the reductive elimination from II to form III was not observed presumably due to the highly challenging C(sp3)–O reductive elimination. With the decrease in the size of alkynyl substituent R1, the coupling of olefin and aldehyde would be favored to form nickellacycle IV. β-Hydride elimination from IV followed by reductive elimination would form the ketone VI [cycloadducts 71 and 72 (Scheme 25)].

Scheme 26.

Proposed Mechanism for the Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Enynes and Aldehydes

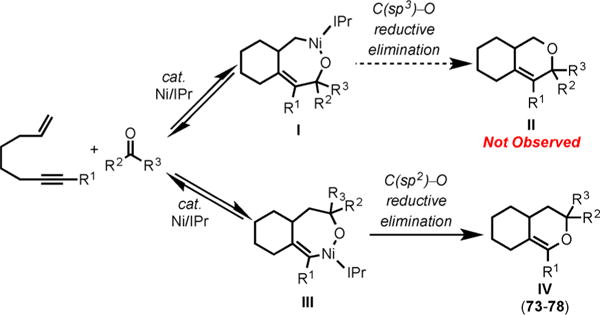

The Ni/SIPr system also catalyzed the cycloaddition of variety of enynes and ketones (Scheme 27).15b Importantly, formation of pyrans arising from chemoselective coupling of the ketone O atom and the alkynyl carbon, rather than the alkenyl carbon atom, was observed exclusively.

Scheme 27.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Enynes and Ketones

The chemoselective formation of the observed pyrans could be rationalized by our mechanistic proposal shown in Scheme 28. Although two distinct pyrans (II and IV) could be formed, pyrans IV are favored since a C(sp2)–O bond reductive elimination that occurs from the nickellacycle III is more facile than C(sp3)–O reductive elimination from nickellacycle I.

Scheme 28.

Proposed Mechanism for the Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Enynes and Ketones

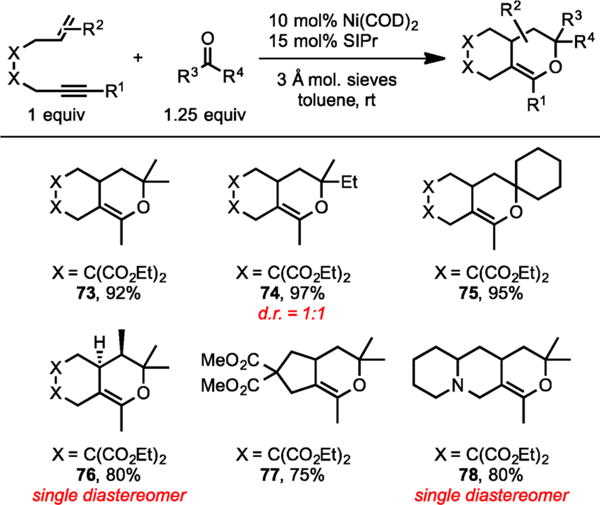

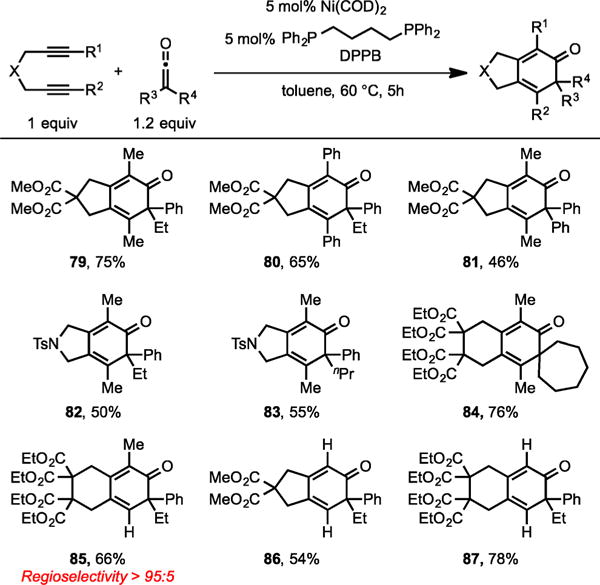

6. Ni-CATALYZED CYCLOADDITION OF DIYNES AND KETENES

Ketenes are highly challenging substrates for transition-metal-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions due to their facile decomposition to form stable, unreactive metal–carbonyl complexes as well as their inherent tendency to dimerize under thermal conditions.16 In 2011, we successfully addressed this challenge by developing a Ni(0)/DPPB [DPPB = 1,4-bis-(diphenylphosphino)butane] system that can efficiently catalyze the cycloaddition of diynes and ketenes to form cyclohexadienones bearing an all-carbon quaternary stereo-center (Scheme 29).17 This methodology had a broad substrate scope in terms of both diynes and ketenes (79–87). Importantly, terminal diynes were tolerated to afford cycloadducts 86 and 87 in good yields.

Scheme 29.

Ni/DPPB-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Ketenes

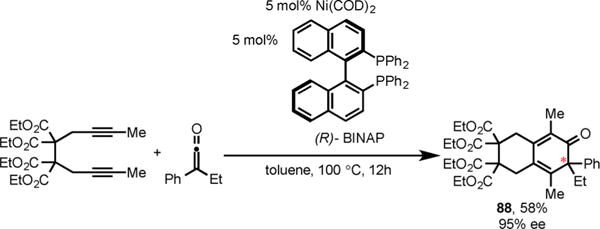

We also briefly investigated the asymmetric cycloaddition of diynes and ketenes. The use of catalytic amounts of Ni(COD)2 and chiral BINAP ligand afforded the cyclohexadienone 88 in excellent enantioselectivity (95% ee) and good yield (Scheme 30). However, a more general and effective asymmetric version of this cycloaddition is yet to be discovered.

Scheme 30.

Enantioselective Ni/BINAP-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diyne and Ketene

7. Ni-CATALYZED CYCLOADDITION OF DIYNES AND TROPONE

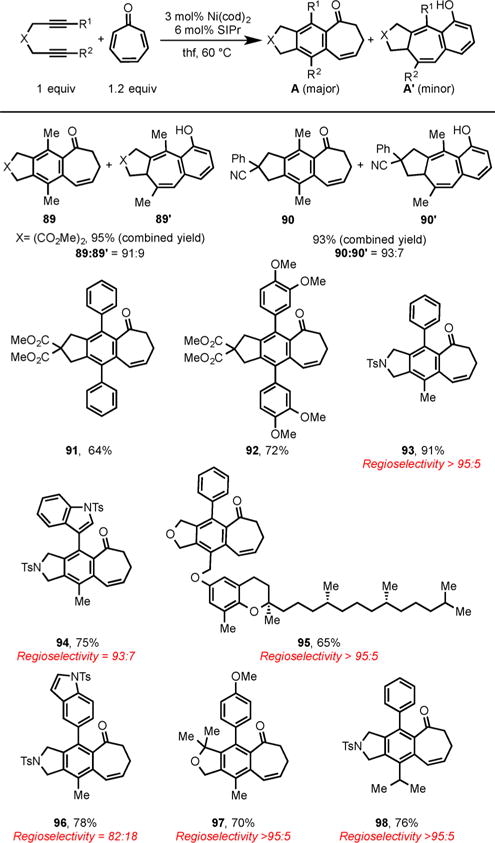

Tropone, a 6π-electron-containing nonbenzenoid aromatic, has been extensively utilized as a versatile coupling partner in many higher order cycloaddition reactions such as [6 + 2], [6 + 3], [6 + 4], [8 + 2], and [8 + 3] cycloadditions to afford the complex bridged cores of a variety of natural products and biologically active molecules.18 However, due to the conjugated nature of tropone, selective activation of a single C–C π-bond of tropone in cycloaddition reactions was challenging. Recently, we addressed this long-standing challenge by developing a Ni/SIPr-catalyzed cycloaddition of diynes with a single double bond of a tropone to selectively form fused tricyclic frameworks in high yields (Scheme 31).19 The cycloaddition of 2,7-diynes bearing alkyl groups on alkyne termini led to the formation of [5–6–7] fused major products (89 and 90) and [5–7–6] minor products (89′ and 90′) in excellent combined yields. Symmetrical aryl-substituted diynes and unsymmetrical aryl–alkyl substituted diynes also underwent smooth cycloaddition to selectively form the desired major products (91–98).

Scheme 31.

Ni/SIPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Tropone

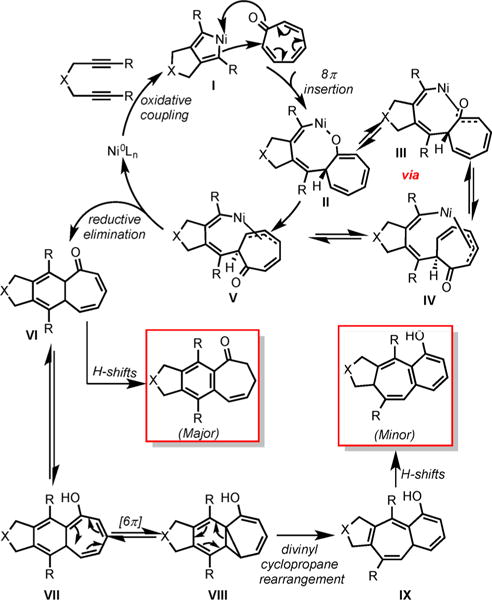

Through DFT calculations, we found that unlike Ni-catalyzed cycloadditions of diynes with CO2, isocyanates, nitriles, etc., the cycloaddition of diynes and tropone involves homo-oxidative coupling of the alkyne units to form nickel-lacyclopentadiene intermediate I, which undergoes an 8π-insertion of tropone to form η1-alkoxy-Ni(II) complex, II (Scheme 32). This intermediate isomerizes to η3-coordinated-Ni(II) complex V, through intermediates III and IV. Reductive elimination from V forms the tricyclic intermediate VI and regenerates the Ni(0) catalyst. Aromatization of VI through hydride shifts affords the [5–6–7] fused major cycloadduct. In addition, a series of tautomerization, rearrangements, and hydride shifts from intermediate VI results in the formation of [5–7–6] fused minor product.

Scheme 32.

Proposed Mechanism for Ni-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Tropone

8. Ni-CATALYZED CYCLOADDITION OF ALKYNES AND DIENES WITH HETEROATOM-SUBSTITUTED CYCLOBUTANONES VIA C–C ACTIVATION

To further advance this field of Ni-catalyzed cycloadditions, we sought to develop Ni catalysts that can activate the thermodynamically and kinetically more challenging C–C σ-bond in cycloaddition reactions. The use of small strained cyclic systems, such as cyclopropanes and, to a lesser extent, cyclobutanones, is a common approach wherein the strain energy released provides the required driving force for the C–C activation.20 We were particularly interested in developing an effective protocol for the C–C activation of heteroatom-substituted cyclobutanones to form heterocycles. We developed a highly efficient Ni/PPh3-catalyzed intermolecular insertion of alkynes into the C(sp2)–C(sp3) σ-bond of 3-azetidinones to form biologically important 3-piperidinone motifs (Scheme 33).21a The cycloaddition of sterically biased alkyne, such as 4,4-dimethylpent-2-yne, led to the regioselective formation of cycloadduct 101, in which the tBu group is placed away from the carbonyl group. The cycloaddition of mixed aryl–alkyl and heteroaryl–alkyl alkynes with 3-azetidinone also led to regioselective formation of substituted 3-piperidinones (102–107), in which the alkyl group is proximal to the carbonyl group. Importantly, this methodology tolerates alkynes bearing SnBu3 and SiMe3 groups, which provide opportunity for the postreaction modification of these 3-piperidinone products.

Scheme 33.

Ni/PPh3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Alkynes and 3-Azetidinones

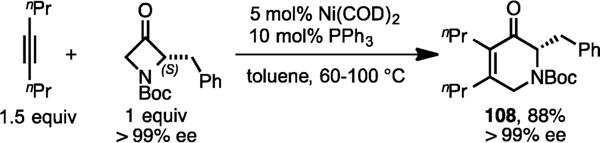

The cycloaddition of chiral 2-substituted azetidinone such as (S)-2-benzyl-1-boc-3-azetidinone with 4-octyne led to the regioselective formation of the cycloadduct 108 (Scheme 34), which suggests the selective insertion of alkyne into the unsubstituted C(sp2)–C(sp3) σ-bond of 3-azetidinone. Gratifyingly, complete retention of enantioselectivity was observed in the cycloadduct 108.

Scheme 34.

Ni/PPh3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of 4-Octyne and Chiral 2-Substituted Azetidinone

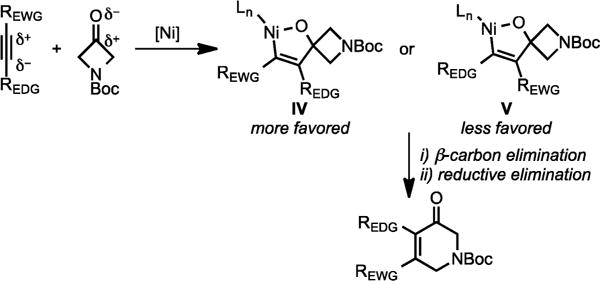

We believe these cycloadditions begin with an initial oxidative coupling between the cyclobutanone carbonyl group and the alkyne (Scheme 35), as was observed in our ketone and aldehyde cycloadditions described in section 5. However, when unsymmetrical alkynes are employed, formation of nickellacycle I is favored over II, which is governed by steric hindrance between the bulky substituent RL and the strained four-membered ring present in II. C–C activation occurs via β-carbon elimination from I to form intermediate III that ultimately regioselectively affords 3-piperidone product.

Scheme 35.

Proposed Mechanism for the Ni/PPh3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Sterically Biased Alkynes with 3-Azetidinones

However, when partially polarized alkynes, such as mixed aryl–alkyl, silyl–aryl, and stannyl–aryl alkynes, are employed, the high regioselectivity observed could be rationalized by preferential polarity-based oxidative coupling of alkyne and azetidinone (Scheme 36). That is, formation of nickellacycle IV would be favored over V, since it involves the Ni-mediated nucleophilic attack of the partially negatively charged carbon of alkyne to the partially positively charged carbonyl.21a,b

Scheme 36.

Proposed Mechanism for the Ni/PPh3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Electronically Biased Alkynes with 3-Azetidinones

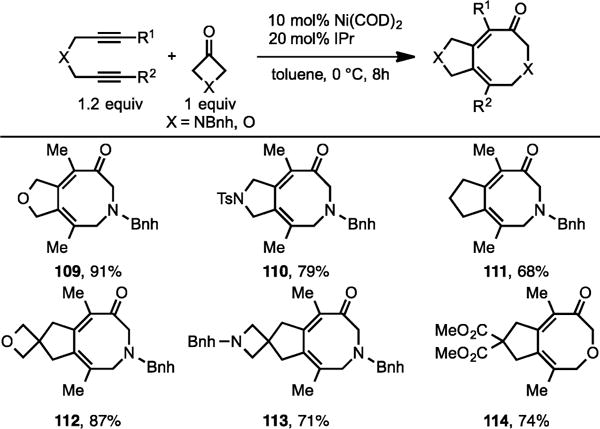

We extended this chemistry to the cycloaddition of diynes with 3-azetidinone and 3-oxetanone to form eight-membered heterocycles. Again, our Ni/IPr system effectively converted a variety of 2,7-diynes to form [5,8]-fused heterocycles (Scheme 37).22

Scheme 37.

Ni/IPr-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes with 3-Azetdidinones and 3-Oxetanones

To further advance the Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions of these strained four-membered heterocycles, we recently developed a Ni/P(p-tol)3-catalyzed cycloaddition of 1,3-dienes with 3-azetidinones and 3-oxetanones (Scheme 38).23 Both acyclic and cyclic dienes were coupled to afford monocyclic and bicyclic eight-membered heterocycles in high yields.

Scheme 38.

Ni/P(p-tol)3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of 1,3-Dienes with 3-Azetidinones and 3-Oxetanones

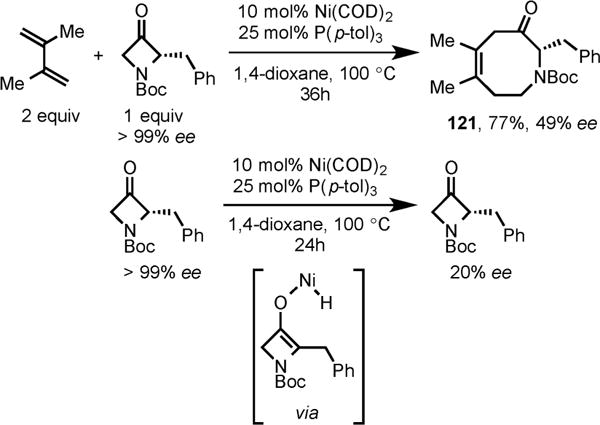

Regioselective insertion of diene was observed with enantiopure 2-substituted azetidinone to form the cycloadduct 121 in high yield (Scheme 39). However, this heterocyclic product retained only 49% enantioselectivity, which was discovered to be the result of partial racemization of chiral 2-substitued azetidinone via a reversible Ni-mediated C–H activation under the reaction conditions.

Scheme 39.

Ni/P(p-tol)3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diene with Chiral 2-Substituted Azetidinone and Loss of Enantioselectivity of Chiral Azetidinone

Our mechanistic proposal for the formation of these heterocyclic products is shown in Scheme 40. Oxidative coupling of diene with the carbonyl group of 3-azetidinone/3-oxetanone forms intermediate I, which undergoes β-carbon elimination to afford nickellacycle II. Isomerization of II to intermediate III allows two different reductive elimination pathways to form either the piperidine product, which was observed in the case of conjugated diene, or the eight-membered heterocyclic product, which is observed in the cycloaddition of 2,3-disubstitued-butadienes.

Scheme 40.

Proposed Mechanism of Ni/P(p-tol)3-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of 1,3-Dienes with 3-Azetidinones and 3-Oxetanones

9. CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

Ni-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions represent a powerful strategy to synthesize carbocycles and heterocycles. A variety of unsaturated coupling partners can be combined in both intramolecular and intermolecular fashion to construct cycloadducts in an efficient manner. The introduction of NHC ligands in Ni catalysis provided the foundation of our work and also offered opportunities to introduce new coupling partners in cycloaddition reactions. Mechanistic investigations further enhanced our understanding of these Ni-catalyzed processes and enabled us to develop new concepts in cycloaddition chemistry. Despite these advances, this area of catalysis is still evolving. Further mechanistic analysis is imperative in order to expand the synthetic utility of these cycloaddition reactions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NSF (Grants 0345432, 0911017, and 1213774), NIH (Grant GM076125), American Chemical Society (Cope Scholar Award), Camille Dreyfus Foundation (Teacher-Scholar Award), Sloan Foundation, and Merck for generous support of this work. We are also indebted to our co-workers, whose names are cited in the references, for their intellectual and experimental contributions.

Biographies

Ashish Thakur was born and raised in Palampur, India. He earned B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in Chemistry from Panjab University, Chandigarh, India. He completed his Ph.D. in 2015 at University of Utah under the supervision of Professor Janis Louie. His Ph.D. research involved the synthesis of interesting carbocycles and heterocycles using Ni and Pd catalysis.

Janis Louie was born and raised in San Francisco, CA. She earned B.Sc. degree in Chemistry from the University of California, Los Angeles, and her Ph.D. from Yale University for work with Professor John Hartwig. After a postdoctoral fellowship with Professor Robert H. Grubbs at the California Institute of Technology, she joined the faculty at the University of Utah in 2001. Her research interests include organometallic catalysis and development of new synthetic methodology.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Published as part of the Accounts of Chemical Research special issue “Earth Abundant Metals in Homogeneous Catalysis”.

References

- 1.(a) Hoberg H, Oster BW. Nickelaverbindungen als zwischenkomplexe der [2 + 2+2′]-cycloaddition von alkinen mit isocyanaten zu 2-pyridonen. J Organomet Chem. 1983;252:359–364. and references therein. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsuda T, Morikawa S, Sumiya R, Saegusa T. Nickel(0)-catalyzed cycloaddition of diynes and carbon dioxide to give bicyclic.alpha.-pyrones. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3140–3145. [Google Scholar]; (c) Saito S, Nakagawa S, Koizumi T, Hirayama K, Yamamoto Y. Nickel-Mediated Regio- and Chemoselective Carboxylation of Alkynes in the Presence of Carbon Dioxide. J Org Chem. 1999;64:3975–3978. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartwig JF. In: Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis. Negishi EI, editor. Vol. 1. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2002. pp. 1097–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Leitner W. Carbon Dioxide as a Raw Material: The Synthesis of Formic Acid and Its Derivatives from CO2. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:2207–2221. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chopade PR, Louie J. [2 + 2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions Catalyzed by Transition Metal Complexes. Adv Synth Catal. 2006;348:2307–2327. [Google Scholar]; (c) Louie J. Transition Metal Catalyzed Reactions of Carbon Dioxide and Other Heterocumulenes. Curr Org Chem. 2005;9:605–623. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yeung CS, Dong VM. Catalytic Making C-C Bonds from Carbon Dioxide via Transition-Metal Catalysis. Top Catal. 2014;57:1342–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Louie J, Gibby JE, Farnworth MV, Tekavec TN. Efficient Nickel-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition of CO2 and Diynes. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15188–15189. doi: 10.1021/ja027438e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tekavec TN, Arif AM, Louie J. Regioselectivity in nickel(0) catalyzed cycloadditions of carbon dioxide with diynes. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7431–7437. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar P, Louie J. Transition-Metal-Mediated Aromatic Ring Construction. Wiley, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2013. Nickel-Mediated [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition; pp. 37–69. Chapter 2. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earl RA, Vollhardt KPC. The preparation of 2(1H)-pyridinones and 2,3-dihydro-5(1H)-indolizinones via transition metal mediated cocyclization of alkynes and isocyanates. A novel construction of the antitumor agent camptothecin. J Org Chem. 1984;49:4786–4800. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto Y, Takagishi H, Itoh K. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of 1,6-Diynes with Isocyanates Leading to Bicyclic Pyridones. Org Lett. 2001;3:2117–2119. doi: 10.1021/ol016082t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duong HA, Cross MJ, Louie J. Nickel-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Alkynes and Isocyanates. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11438–11439. doi: 10.1021/ja046477i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duong HA, Louie J. Regioselectivity in nickel(0)/phosphine catalyzed cycloadditions of alkynes and isocyanates. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:5098–5104. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duong HA, Louie J. A nickel(0) catalyzed cycloaddition of alkynes and isocyanates that affords pyrimidine-diones. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7552–7559. [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Souza BR, Louie J. Nickel-Catalyzed Cycloadditive Couplings of Enynes and Isocyanates. Org Lett. 2009;11:4168–4171. doi: 10.1021/ol901703t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Takahashi T, Tsai FY, Kotora M. Selective Formation of Substituted Pyridines from Two Different Alkynes and a Nitrile: Novel Coupling Reaction of Azazirconacyclopentadienes with Alkynes. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4994–4995. [Google Scholar]; (b) Eisch JJ, Ma X, Han KI, Gitua JN, Kruger C. Mechanistic Comparison of the Nickel(0)-Catalyzed Homo-Oligomerization and Co-Oligomerization of Alkynes and Nitriles. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2001;2001:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) McCormick MM, Duong HA, Zuo G, Louie J. A Nickel-Catalyzed Route to Pyridines. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5030–5031. doi: 10.1021/ja0508931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stolley RM, Maczka MT, Louie J. Nickel-Catalyzed [2 + 2+2] Cycloaddition of Diynes and Cyanamides. Eur J Org Chem. 2011;2011:3815–3824. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201100428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kumar P, Prescher S, Louie J. A Serendipitous Discovery: Nickel Catalyst for the Cycloaddition of Diynes with Unactivated Nitriles. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:10694–10698. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Stolley RM, Duong HA, Thomas DR, Louie J. The Discovery of [Ni(NHC)RCN]2 Species and Their Role as Cycloaddition Catalysts for the Formation of Pyridines. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15154–15162. doi: 10.1021/ja3075924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Stolley RM, Duong HA, Louie J. Mechanistic Evaluation of the Ni(IPr)2-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Alkynes and Nitriles To Afford Pyridines: Evidence for the Formation of a Key η1-Ni(IPr)2(RCN) Intermediate. Organometallics. 2013;32:4952–4960. doi: 10.1021/om400666k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhong Y, Spahn NA, Stolley RM, Nguyen MH, Louie J. 3,5-Disubstituted 2-Aminopyridines via Nickel-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Terminal Alkynes and Cyanamides. Synlett. 2015;26:307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Tsuda T, Kiyoi T, Miyane T, Saegusa T. Nickel(0)-catalyzed reaction of diynes with aldehydes. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:8570–8572. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamamoto Y, Takagishi H, Itoh K. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition of 1,6-Diynes with Tricarbonyl Compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6844–6845. doi: 10.1021/ja0264100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Tekevac TN, Louie J. Nickel-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Unsaturated Hydrocarbons and Carbonyl Compounds. Org Lett. 2005;7:4037–4039. doi: 10.1021/ol0515558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tekavec TN, Louie J. Nickel-Catalyzed Cycloadditions of Unsaturated Hydrocarbons, Aldehydes, and Ketones. J Org Chem. 2008;73:2641–2648. doi: 10.1021/jo702508w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tidwell TT. Ketenes. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar P, Troast DM, Cella R, Louie J. Ni-Catalyzed Ketene Cycloaddition: A System That Resists the Formation of Decarbonylation Side Products. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7719–7721. doi: 10.1021/ja2007627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Wu Y, Zhao Y, Li Z, Zhang l, Yang W, Jiang H, Jing C, Yu H, Wang B, Xiao Y, Guo H. Metal-Catalyzed [6 + 3] Cycloaddition of Tropone with Azomethine Ylides: A Practical Access to Piperidine-Fused Bicyclic Heterocycles. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2625–2629. doi: 10.1021/ja4122268. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar P, Thakur A, Hong X, Houk KN, Louie J. Ni(NHC)]-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Diynes and Tropone: Apparent Enone Cycloaddition Involving an 8π Insertion. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:17844–17851. doi: 10.1021/ja5105206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Jun CH, Park JW. Directed C – C Bond Activation by Transition Metal Complexes. Top Organomet Chem. 2007;24:117–143. [Google Scholar]; (b) Murakami M, Matsuda T. Metal-catalysed cleavage of carbon-carbon bonds. Chem Commun. 2011;47:1100–1105. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02566f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Kumar P, Louie J. A Single Step Approach to Piperidines via Ni-Catalyzed β-Carbon Elimination. Org Lett. 2012;14:2026–2029. doi: 10.1021/ol300534j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ho KYT, Aïssa C. Regioselective Cycloaddition of 3-Azetidinones and 3-Oxetanones with Alkynes through Nickel-Catalysed Carbon–Carbon Bond Activation. Chem - Eur J. 2012;18:3486–3489. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Zhang K, Louie J. An Expeditious Route to Eight-Membered Heterocycles By Nickel-Catalyzed Cycloaddition: Low-Temperature Csp2–Csp3 Bond Cleavage. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:8602–8606. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakur A, Facer ME, Louie J. Nickel-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of 1,3-Dienes with 3-Azetidinones and 3-Oxetanones. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:12161–12165. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]