Next generation sequencing (NGS) holds potential for improving clinical and public health microbiology.1 In addition to identifying pathogens faster and more precisely, high-throughput technologies and bioinformatics can provide new insights into disease transmission, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance. The US public health system is integrating pathogen genome sequencing into infectious disease surveillance with support from the Advanced Molecular Detection (AMD) program established by Congress at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2014.2 Population-level data on pathogen genomes in turn supports the development of more precise and efficient clinical diagnostics. In time, laboratories may be able to replace many traditional microbiology processes with a single workflow that accommodates a wide array of pathogens.3

How Next Generation Sequencing of Pathogens Works

NGS is a versatile technology, broadly applicable to viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites, animal vectors, and human hosts. Choosing among available methods depends on sequencing objectives and involves tradeoffs in accuracy, efficiency and cost.4 For routine sequencing, most US clinical and public health microbiology laboratories use short-read sequencing platforms (such as Illumina MiSeq, San Diego, CA), which produce sequence fragments up to 1000 base-pairs long.. Although microbial genomes are generally smaller and less complex than human genomes, long-read sequencing technologies (such as single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA) are useful for constructing complete, highly accurate genomes and sorting out plasmids, repeats, and other complex regions.

A different approach, nanopore sequencing, relies on threading individual DNA or RNA molecules through engineered protein nanopores and monitoring the electric current across each pore. The first such commercially available instrument, the MinION (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, UK), offers relatively long sequence reads and allows data analysis to begin while sequencing is still in progress.Early limitations in throughput and accuracy have been mitigated by continued improvements in hardware and reagents. Because of device portability, fast sample preparation, flexibility, and relatively low cost, nanopore sequencing is becoming a feasible first-line strategy for pathogen sequencing in clinical and public health settings.4,5

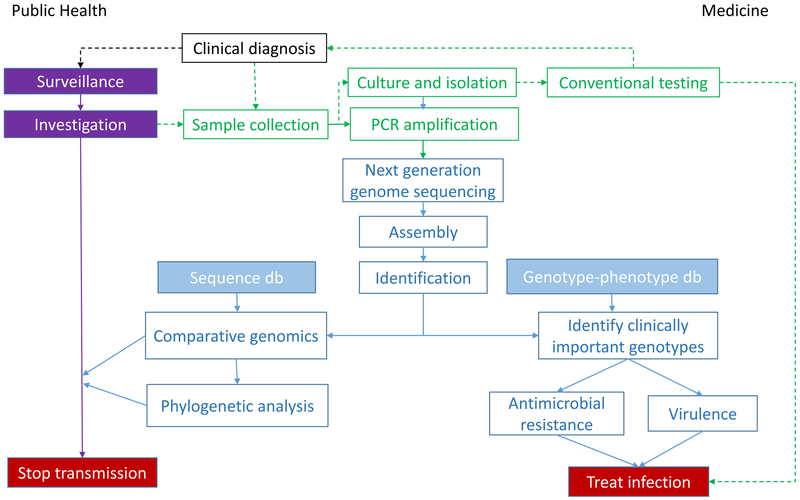

The transformation of raw sequence data into actionable information is complex and computationally intensive (Figure). The first step is typically to assemble shorter fragments into a complete sequence, either by mapping against a known reference genome or by assembling the sequence de novo using overlapping reads. Comparing the assembled genome with reference strains facilitates many different inferences, such as pathogen identification, high-resolution strain typing, and prediction of important phenotypic characteristics (e.g., virulence, antimicrobial resistance). Well-curated and up-to-date reference databases are crucially important because microbial pathogens evolve rapidly and bacteria can exchange plasmids—often encoding virulence and antimicrobial resistance traits—across strains and species.. Assembled genomes can be compared with others to look for phylogenetic clustering as evidence of transmission. Each step—assembly, strain typing, phenotyping, and clustering—requires different bioinformatics tools that must be harmonized into a consistent workflow.4,5

Figure :

[Slide 1] Workflow transforming pathogen genome sequence data into actionable information.

[Slide 2, legend indicating data sources.]

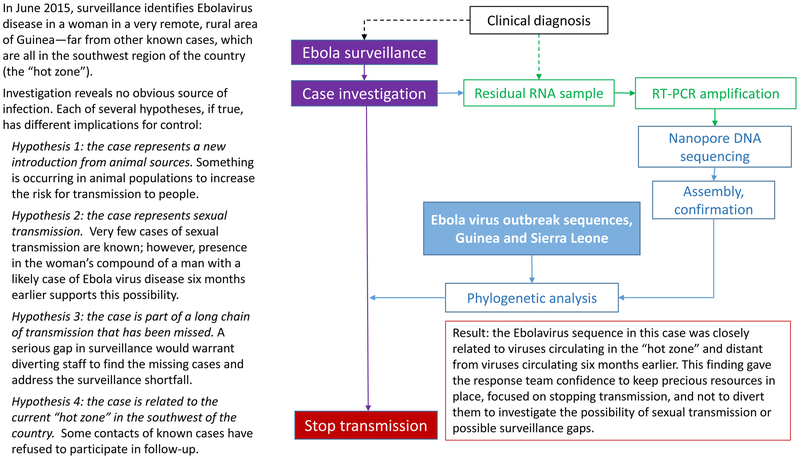

[Slide 3] Example: Use of nanopore sequencing to distinguish among possible routes of Ebola virus transmission.

Important Practice Considerations

In public health, NGS offers crucial advantages for surveillance and outbreak investigation in terms of speed and resolution of sequence differences.1 For example, the transition to NGS from an older molecular method (pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, PFGE) is well underway in PulseNet, the foodborne disease surveillance system maintained by CDC and its public health partners. PulseNet is now able to detect outbreaks earlier, to distinguish clusters of related cases more accurately, and to link illnesses to potential contaminated food sources more quickly.4

Integrating pathogen genomics with epidemiology is enhancing public health efforts to prevent transmission of communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis (TB).6 Genotyping TB isolates can corroborate transmission inferred from contact investigations or suggest connections among apparently unrelated cases, helping health departments to better focus their resources. NGS has the potential to yield information on likely anti-mycobacterial drug susceptibility more quickly than conventional testing, enabling more specific and timely treatment.7

NGS data are amenable to standardization and sharing, important advantages for global health partnerships like the World Health Organization’s (WHO) influenza surveillance system. An open, “sequencing first” approach can help produce timely and accurate data for selection of candidate influenza vaccines, quickly identifying prevalent variants while monitoring the dynamics of co-circulating viral populations.1

NGS also offers advantages for challenging field investigations. In one example, a research team from the United Kingdom packed a nanopore sequencing laboratory into standard luggage for transport to Guinea during the 2015 Ebola outbreak.8 During an 8-month period, they sequenced 142 Ebola virus genomes on site, usually within one working day; data were transmitted to the cloud for analysis and results returned the next day. Despite significant logistical challenges, including unreliable electrical power and internet service, the team provided actionable information for epidemic response without exporting samples from the country. The Figure describes an example of how these data helped inform outbreak control strategy.

US public health laboratories, with support from the AMD program, are rapidly adopting NGS for surveillance and investigation of foodborne disease, TB, hepatitis C, Legionella, and other pathogens.2 Nevertheless, the transition from research to routine public health and clinical use faces substantial challenges.4 At the laboratory level, these include infrastructure, workforce development, efficiency and cost. At a broader, systemic level, substantial efforts are needed to develop standard protocols, proficiency-testing programs, professional guidelines, and regulatory requirements.3,9

Value

Compared with conventional methods, NGS increases speed, accuracy, and detail, but also increases cost. For example, a CDC analysis (unpublished data) estimated that NGS cost approximately $150–200 per bacterial isolate, compared with $94 for PFGE. Consolidating workflows for multiple pathogens may improve laboratory efficiency and help offset this cost; however, the transition to NGS also entails significant up-front investment in laboratory equipment, computer resources, and training. Much more information will be needed to evaluate the value of NGS technologies for microbiology at patient, programmatic, and societal levels.

Evidence

Evidence-based guidelines exist for only a few specific, clinical uses of pathogen sequence data, for example, in selecting antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection (SORT evidence level A). Informative sequences from bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasite genomes are the basis for many new, nucleic acid-based diagnostic tests, including “point-of-care” tests that bypass the microbiology laboratory completely. As multiplex panels for syndromic diagnosis (e.g., for diarrhea) become more widely used, systematic efforts are needed to assess their clinical validity and utility, as well as their effect on laboratory-based public health surveillance.

Bottom Line

NGS is transforming the public health approach to infectious diseases, as well as the treatment of individual patients. Better coordination in establishing quality standards, reporting, and interpretation of NGS data could make these efforts synergistic. 9

Acknowledgments

Disclaimers:

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Office of Advanced Molecular Detection, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Brief glossary of terms in pathogen genome sequencing

- High-throughput sequencing

Also called “next generation sequencing,” since the mid-2000’s has largely replaced Sanger sequencing; generally divided into short-read (<500- to 1000-base read lengths) and long-read (>1000-base read lengths) technologies, although there is no distinct cut-off.

- Read length

The number of bases in a continuous sequence fragment; longer read-lengths improve the ease and accuracy of genome assembly.

- Coverage (read depth)

The average number of reads that include a given nucleotide in the reconstructed sequence.

- Assembly

Organizing overlapping reads into longer sequences, up to and including full-length genomes.

- Strain typing

Distinguishing among different variants of the same bacterial or viral species.

- Phenotyping

Characterizing microbial biological properties, such as virulence or antimicrobial resistance.

- Clustering

Phylogenetic analysis of sequence differences to assess relatedness, used in combination with epidemiologic data to infer transmission.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Contributor Information

Marta Gwinn, CFOL International, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road, mailstop E-61, Atlanta, Georgia 30333.

Duncan MacCannell, Office of Advanced Molecular Detection, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Gregory L. Armstrong, Office of Advanced Molecular Detection, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Gwinn M, MacCannell DR, Khabbaz RF. Integrating advanced molecular technologies into public health. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(3):703–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advanced Molecular Detection. https://www.cdc.gov/amd. Published October 2016. Accessed June 25, 2018.

- 3.American Academy of Microbiology. Applications of clinical microbial next-generation sequencing. https://www.asm.org/index.php/colloquium-reports/item/4462-applications-of-clinical-microbial-next-generation-sequencing. Published February 2016. Accessed June 22, 2018.

- 4.Besser J, Carleton HA, Gerner-Smidt P, Lindsey RL, Trees E. Next-generation sequencing technologies and their application to the study and control of bacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(4):335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quainoo S, Coolen JPM, van Hijum SAFT, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of bacterial pathogens: the future of nosocomial outbreak analysis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(4):1015–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guthrie JL, Gardy JL. A brief primer on genomic epidemiology: lessons learned from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1388(1):59–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CRyPTIC Consortium and the 100,000 Genomes Project. Prediction of susceptibility to first-line tuberculosis drugs by DNA sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2018. September 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quick J, Loman NJ, Duraffour S, et al. Real-time, portable genome sequencing for Ebola surveillance. Nature. 2016;530(7589):228–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gargis AS, Kalman L, Lubin IM. Assuring the quality of next-generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and public health laboratories. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(12):2857–2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]