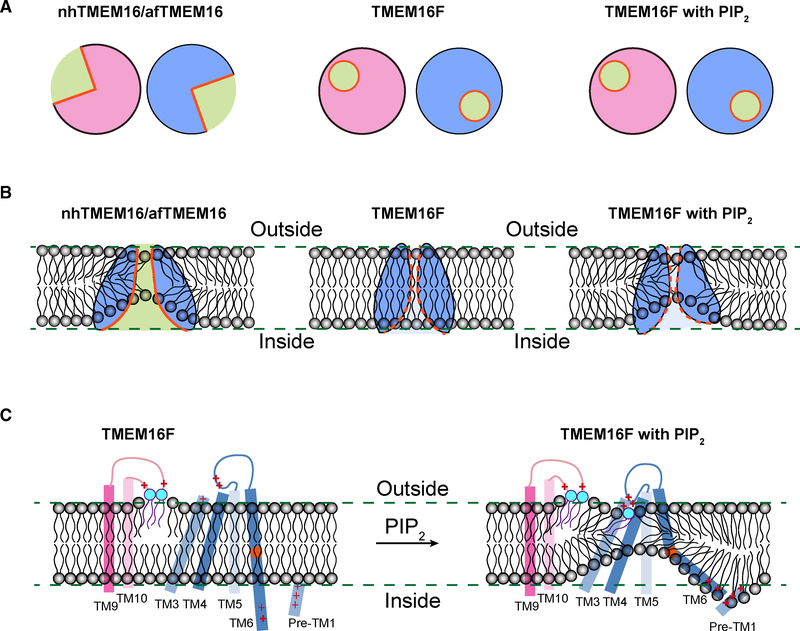

Figure 7. Model for Lipid Scrambling.

(A) Schematics showing the half-open subunit cavity of the fungal scramblases nhTMEM16 and afTMEM16 (left) and the intact enclosed channel pore ofTMEM16F, which has dual function of channel and scramblase, in the presence (right) or absence (middle) of PIP2 that causes changes of TMEM16F conformation. The cross section of dimeric TMEM16F in nanodiscs with or without PIP2 supplement is very similar.

(B) Membrane distortion is associated with fungal scramblases with half-open subunit cavity (left). Whereas TMEM16F in nanodiscs without PIP2 supplementation is not associated with membrane distortion, PIP2-induced conformation changes of TMEM16F causes membrane distortion near the enclosed channel pore (right).

(C) In addition to the two lipids stably bound to clusters of basic residues in the TM9-TM10 loop of Ca2+-bound TMEM16F, a lipid (likely PS) is bound to basic residues on TM4 and the TM4-TM5 loop of Ca2+-bound TMEM16F in PIP2-supplemented nanodiscs. PIP2 induces displacements of TM3, TM4, and TM6, which displays a kink to bring clusters of basic residues on TM6 and the pre-TM1 elbow together, thereby causing membrane distortion. Alanine substitutions of a subset of these basic residues involved in lipid binding and membrane distortion specifically affect PS exposure, indicating that lipid scrambling may proceed in a pathway separable from ion permeation.