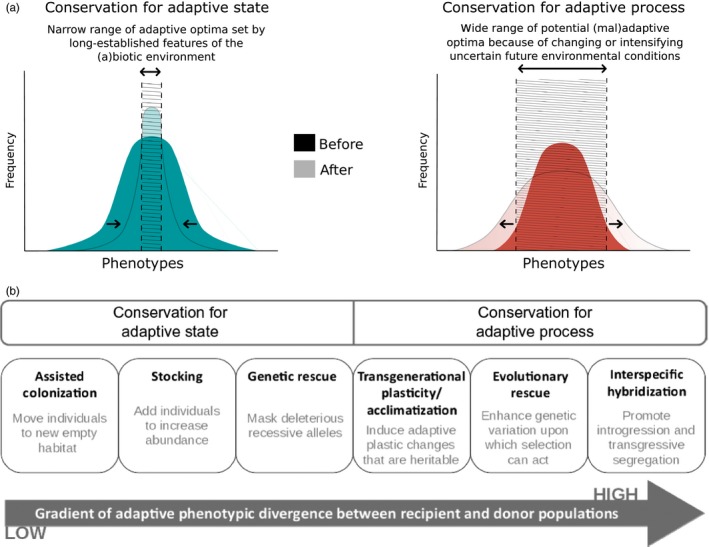

Figure 1.

A conceptual classification for considering conservation goals that seek to reduce or integrate (mal)adaptation. (a) Adaptive state versus adaptive process. In both panels, the darker and lighter shading indicates the population trait or fitness frequency before and after implementing a conservation practice, respectively. Adaptive state assumes that the population is replenished with individuals so that its fitness returns to a known adaptive optimum presumably set by some long‐established features of the (a)biotic environment. This is illustrated by a narrow range of possible adaptive optima along the phenotype axis in the hatched area of “after” histogram. The result is the mean population fitness closely matches the optimal phenotype, at a given time point, at the expense of reduced heritable trait variation. Adaptive process, by contrast, assumes that the optimal phenotype in the future is uncertain because (i) there are multiple (mal)adaptive optima to which it is unknown the population will evolve into the future, or (ii) that a sustained adaptive process will be required to a reach a new optimum in the presence of an intensifying stressor, which may be far from any known phenotype. This is illustrated by the broad range of possible (mal)adaptive optima along the phenotype axis in the hatched area of the “after” histogram. The result is that the heritable trait variation is increased at the expense of reduced mean population fitness in relation to the optimal phenotype. (b) Examples of conservation strategies that occur along a continuum of conservation goals between adaptive state and process. Whereas adaptive state conservation strategies involve the admixture of adaptively similar populations to minimize maladaptation and optimize mean population fitness, adaptive process conservation strategies involve the admixture of adaptively divergent populations to increase heritable (mal)adaptive variation