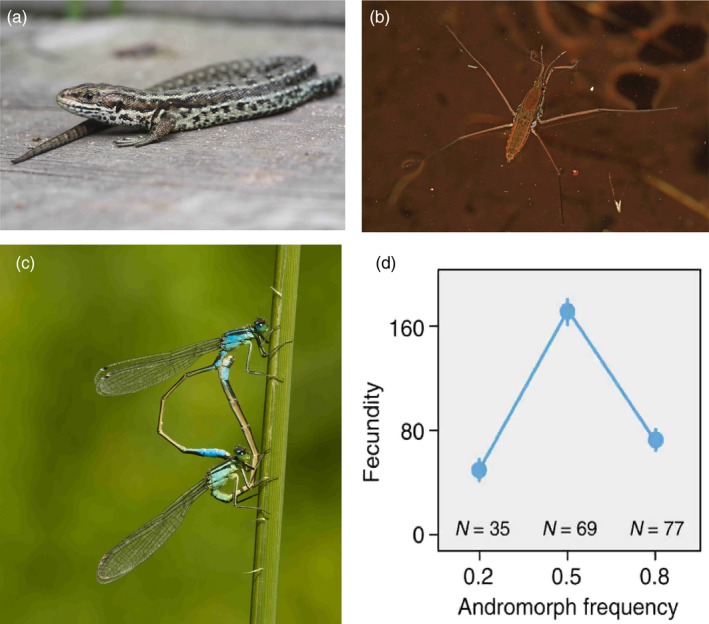

Figure 3.

Empirical examples of studies that link sexual conflict and frequency‐dependent selection to mean population fitness. (a) In common lizards (Zootoca vivipara), male‐biased sex ratios in field enclosures lead to sexual conflict and population collapse, due to reduced female fitness and thereby reduced population fitness (photograph by Alastair Rae/Wikimedia Commons). (b) Similarly, in water striders (Aquarias remigis) sexual conflict favours aggressive males within populations which harass females and thereby depress population mean fitness, whereas the spread of such aggressive male phenotypes is opposed by higher‐level selection and presumably higher extinction risk of populations with a high frequency of aggressive males (photograph by Judy Gallagher/Wikimedia Commons). (c) In the common bluetail damselfly (Ischnura elegans), there are three heritable female colour morphs, one which is male coloured (“male mimics”), and these three morphs are maintained by frequency‐dependent sexual conflict (Le Rouzic et al., 2015; Svensson et al., 2005). Here is a male mating with a male mimic (Photograph by Erik Svensson). (d) Experimental manipulations of the frequency of the male mimic in field enclosures reveal that average female fecundity (closely connected to population mean fitness) is maximized at intermediate morph frequencies, providing a link between sexual conflict, genetic variation, frequency‐dependent selection and population mean fitness (Takahashi et al., 2014)