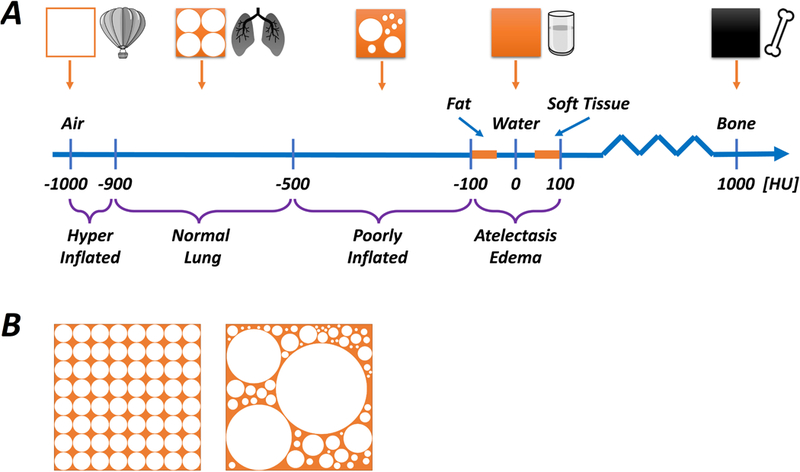

Figure 2:

Schematic illustration of CT densities relative to air, normal lung, water and bone (Panel A). The smallest unit of imaged tissue is called a voxel (≈ 1 mm3), and the average density, expressed as Hounsfield Units (HU), of each voxel is determined by its contents. Higher density contents absorb more radiation and the image is whiter, whereas lower density contents absorb less radiation and the image is darker. If a voxel was composed entirely of air, water or bone it would have densities of -1000 HU, 0 HU and +700 HU, respectively. The density of fat, water and soft tissue are similar (fat ≤ water ≤ soft tissue), and normally aerated lung tissue (corresponding approximately to 50-70% air, 30-50% tissue) has a density of < -500 HU. Therefore, a hyperinflated region of lung (more air, less tissue) would have a density of far less than -500 HU (generally < -900 HU), whereas an area with substantial consolidation or atelectasis will have density of more than -100 HU. Areas with decreased (but not eliminated) aeration, called ‘poorly aerated’ lung, have density in the range of -500 to -100 HU. Panel B illustrates a range of possible content combinations within a single voxel. It is important to understand that the maximum resolution for CT is limited by the size of the voxel, and each voxel can only yield a single ‘net’ value for density. Thus, the illustrated voxels, while having different individual constitutions, each have a similar ‘average’ density expressed as HU.