Abstract

Background

Standardized tests and outcome measures (STOM) have not been consistently implemented as part of most physical therapists’ practice. Incidence of STOM use among physical therapists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center was similar to low levels cited nationally among acute care physical therapists. Targeted knowledge translation (KT) strategies have been suggested to promote the application of research evidence into clinical decision making.

Purpose

The purpose of this quality improvement (QI) effort was to implement a series of interventions aimed at increasing both use and interpretation of STOM by physical therapists practicing in acute care.

Design

This study used an observational longitudinal design.

Methods

A literature review identified current barriers and facilitators to the use of STOM by physical therapists. KT strategies were tailored to the practice setting in order to target barriers and promote facilitators to the use of STOM. Data were collected through retrospective chart review at baseline and then subsequently at 4 periods following the implementation of the QI project.

Results

A statistically significant increase in both the use (primary outcome) and interpretation (secondary outcome) of STOM was observed following the implementation of KT strategies. The increase was sustained at all subsequent measurement periods.

Limitations

Limitations include the lack of a control group and the small number of setting- and diagnosis-specific STOM available for use by physical therapists practicing in acute care.

Conclusions

Implementation of KT strategies was associated with an increase in the frequency of use and interpretation of STOM. Similar QI efforts are feasible in any acute care physical therapy department and potentially other settings.

The use of standardized tests and outcome measures (STOM) has been suggested to improve patient care. Standardized tests and outcome measures contribute to an evidence-based approach to clinical decision making,1 allow physical therapists to quantify observations and compare patient status between examination periods,2,3 facilitate communication and continuity of care for patients transitioning from one health care setting to another,4 increase efficiency of practice,5 help patients recognize improvements in a quantifiable manner, and facilitate reimbursement under Medicare mandates for functional reporting of percentage impairment. Standardized tests and outcome measures also help identify and quantify impairments of body functions and structures, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. One study suggests that without standardized measurement, “clinical recommendations and resource allocation may be subject to excessive variability, error, and bias.”6

Use of STOM may be especially important in the acute care setting in order to establish a baseline status that can then be referenced by physical therapists in successive treatment settings.7 Standardized tests and outcome measures may also inform clinical decision making as it applies to making appropriate discharge recommendations.8,9

Recently published studies have highlighted the limited use of STOM by physical therapists. In 2009, Jette et al10 cited that of the 456 physical therapists surveyed, only 218 (47.8%) indicated that they used standardized outcome measures in practice. Physical therapists working in the acute care setting were the least likely to report use of these measures (16%). Additional studies have reported similarly low frequencies of use among rehabilitation professionals.11,12 Evidence also suggests that even those physical therapists who demonstrate better knowledge of evidence-based practice skills tend to rely on their clinical experience in order to inform their clinical decision making, rather than on evidence-based research.13

In addition to highlighting the low level of STOM use, existing literature also highlights specific barriers and facilitators to the use of STOM in physical therapist practice. In 2011, Swinkels et al14 published a literature review identifying the following barriers to use of STOM among rehabilitation professionals: “lack of time for identification of a suitable measure, its administration and scoring and interpretation of results, lack of administrative support and resources, lack of financial compensation, lack of knowledge (familiarity with, lack of training in), lack of agreement on which measures to use and lack of access to measures.” The authors also noted perceived facilitators, including “knowledge of clinimetrics,” “support of colleagues in the use of measurement instruments,” “active educational initiatives,” “expertise and professional support,” “mandatory reporting of outcome measures,” and “having a master's degree.” Duncan et al15 published a systematic review regarding STOM use by rehabilitation professionals in which similar themes were identified on a continuum from facilitator to barrier including “knowledge, education, and perceived value in outcome measurement; support/priority for outcome measure use; practical considerations; patient considerations.”

In a study focused specifically on physical therapists, Jette et al10 found the most common barriers to the use of STOM were: “length of time for patients to complete them, length of time for clinicians to analyze the data, and difficulty for patients in completing them independently.” Given the lack of STOM use as well as the identified barriers and facilitators to use, Van Peppen12 and his colleagues concluded: “Robust setting-specific tailored implementation strategies based on the reported barriers and facilitators are needed.”

The primary goal of this quality improvement effort (QI) was to implement a set of setting-specific strategies to help inpatient acute care physical therapists at an academic medical center more consistently administer evidence-based STOM. The secondary goal of this QI effort was to increase the frequency of interpretation and application of STOM results given that further exploration of how STOM influence clinical reasoning has also been called for in the literature.16 In order to achieve these outcomes, previously identified barriers to use of STOM were addressed, and previously identified facilitators were promoted in the context of a variety of knowledge translation (KT) strategies.

Knowledge translation strategies have been recommended to physical therapists as a way to bridge the knowledge-to-practice gap in clinical practice.17 The Canadian Institutes of Health Research has defined KT as a “dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system.”18 Recent systematic reviews suggest that participation in active, multi-component KT activities may result in improved self-perceived knowledge of relevant evidence as well as improved ability to incorporate evidence into physical therapist practice.19,20 In this QI effort, multiple active KT strategies were implemented, including mandating the reporting of outcome measures, creation of a local consensus process, incorporation of STOM into the electronic medical record, creation of printed materials, participation in interactive educational sessions, involvement of opinion leaders, and audit and feedback. Each strategy targeted an identified barrier to, and facilitator of, use of STOM (Tab. 1).

Table 1.

Identified Barriers and Corresponding Targeted Knowledge Translation Strategies

| Barrier | Knowledge Translation Strategy |

| Lack of time | – Local consensus process |

| – Printed materials | |

| – Incorporation into electronic health record | |

| Administrative support | – Opinion leaders |

| – Local consensus process | |

| – Interactive educational sessions | |

| Financial compensation | Organizational mandate |

| Knowledge | – Opinion leaders |

| – Interactive educational sessions | |

| – Printed materials | |

| – Incorporation into electronic health record | |

| Access to measures | Printed materials |

| Agreement on measure use | Local consensus process |

The setting for this study was Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), a level-1 trauma center in Boston, Massachusetts, with 463 medical/surgical beds and 77 intensive care unit beds. At the time of implementation of this QI effort, there were 24 to 34 full-time physical therapists working in the inpatient rehabilitation department who rotated to a new unit every 6 months. The experience of these physical therapists varied from months to more than 15 years. All full-time staff had achieved their doctor of physical therapy degree, and 2 therapists were certified clinical specialists. On average, the inpatient rehabilitation department received 300 to 400 new physical therapist consults weekly.

Methods

Intervention

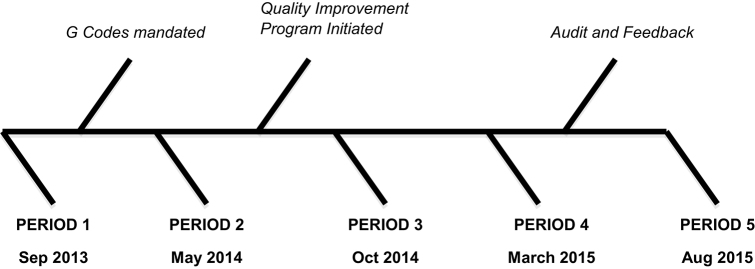

Seven KT strategies were implemented over the course of approximately 2 years based on evidence supporting each strategy in the literature (Fig.). Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Figure.

Seven knowledge translation strategies were implemented over the course of approximately 2 years based on evidence supporting each strategy in the literature.

Mandatory reporting of outcome measures

qPrevious reports have noted mandated use of STOM as a potential strategy to bridge the knowledge-to-practice gap in rehabilitation practice.21 In October 2013, concurrent with the new billing guidelines introduced by the Centers for medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Inpatient Rehabilitation Department manager mandated the use of functional reporting during an episode of physical therapist care. Functional reporting in the United States, commonly billed as a G-code, will ultimately allow CMS to better gather and analyze data regarding patient function and outcomes.22 Although the use of any STOM to quantify level of functional impairment was encouraged at BIDMC, the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) Short Form “6-Clicks” was introduced to staff because of the simplicity of administration and ease of conversion to G-codes.23 At this time, a single easy-to-use pocket card was given to each staff member to assist with accessibility and ease of use of this particular measure.

Local consensus process

The Measures Selection Committee was created to select a specific set of STOM that would be recommended for use to the entire department. The committee was composed of therapists with varying levels of experience and with a variety of clinical interests. The primary goal of the committee was to create a group of 10 STOM that would be appropriate for use in the acute care setting and applicable to most diagnostic groups at BIDMC. The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), the national professional organization for physical therapist practitioners in the United States, has suggested that providing therapists with access to a defined group of acceptable STOM allows for more efficient identification of a measure to use with a specific patient24 (Tab. 2).

Table 2.

Selection Criteria for Inclusion of Standardized Tests and Outcome Measuresa

| Standardized Tests and Outcome Measures | Advantages |

| Timed “Up and Go”41 | – Supported by EDGE38 |

| – Predicts fall risk | |

| Six-Minute Walk Test42 | – Supported by EDGE and American Thoracic Society |

| – Prognostic cutoff scores | |

| Orpington Prognostic Scale43 | – Supported by EDGE |

| – Designed for use in acute care | |

| – Prognostic cutoff scores | |

| – Discharge disposition prediction | |

| Physical Function ICU Test (scored)44 | – Designed for use in acute care |

| – Availability of MCID | |

| Mobility score45 | – Designed for use in acute care |

| – Prognostic cutoff scores | |

| – Discharge disposition prediction | |

| Dynamic Gait Index46 | – Supported by EDGE |

| – Applicable to large patient population | |

| – Predicts fall risk | |

| – Availability of MDCs/MCIDs | |

| Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) “6 Clicks”23 | – Applicable to any patient population |

| – Designed for use in acute care | |

| – Discharge disposition predication | |

| – Availability of MDCs/MCIDs | |

| – Easy conversion to G–code modifiers | |

| Confusion assessment method-ICU47 | – Designed for use in acute care |

| – Prognostic cutoff scores | |

| Comfortable walking speed48 | – Supported by EDGE |

| – Applicable to large patient population | |

| – Availability of MDCs/MCIDs | |

| – Prognostic cutoff scores | |

| – Discharge disposition prediction | |

| – Valid/reliable in acute care | |

| Performance Oriented Mobility Scale49 | – Predicts fall risk |

aEDGE = Evaluation Database to Guide Effectiveness; ICU = intensive care unit; MCID = minimal clinically important difference; MDC = minimal detectable change.

A secondary goal of establishing the committee was to create a sense of ownership for the project among staff. The creation of a local consensus has been part of successful projects aimed at encouraging physical therapists to incorporate evidence into practice.25 Additionally, stakeholder engagement has been identified as an important part of the KT process.26

Electronic health record (EHR) templates

The Measures Selection Committee then created STOM templates for each measure, which were incorporated into the EHR for system. The templates included a variety of relevant psychometric values, such as age- and sex-based population norms, minimal detectable change (MDC), and minimal clinically important difference (MCID), as well as relevant cutoff scores for fall risk, functional prognosis, and/or discharge destination. This information was presented in a variety of sample statements to be pasted into both the objective and assessment portions of a note. These templates gave physical therapists the ability to efficiently consider and document only the most relevant psychometric information as it applied to a specific patient and clinical decision (Appendix 1). Incorporation of standardized measures into EHRs has been successful in improving clinician adherence to completion of standardized assessments according to previous reports.27

Printed materials

All physical therapists were provided with a set of laminated pocket cards for easy reference throughout patient care. The information included on the laminated cards included populations for which each of the standardized measures had been validated, test items, and important, setting-specific considerations for test administration (Appendix 2). The provision of laminated materials for easy reference during the daily routine has been used as part of previously described successful multifaceted interventions to encourage evidence-based practice among physical therapists.28

Interactive educational sessions

Next, this QI effort was introduced to the entire physical therapy department staff between June and July 2014. At that time, participation in an educational session was mandated for every full-time physical therapist. The educational sessions included a review of the benefits of using STOM as part of regular clinical practice, as well as the presentation of the work completed by the Measures Selection Committee. The presentation of each measure included key points regarding proper administration, psychometric properties relevant to clinical decision making in acute care, and considerations for application of STOM to specific patients. Such educational meetings have been shown to increase the use of clinical guidelines including the use of functional outcome measures by clinicians.20

Given that KT is a continual process, the promotion of STOM use was also included in ongoing department-wide, interactive educational sessions, namely, Case Conference and Journal Club. At a monthly Case Conference, the selection and interpretation of a STOM was often discussed in the context of a specific patient case. During Journal Club meetings, staff often critically analyzed the literature supporting different STOM as well as their established psychometric properties. Often these educational sessions resulted in new information that was then incorporated into existing materials available to the staff. Participation in journal clubs has been used as part of previously described successful multifaceted interventions aimed at encouraging evidence-based practice of rehabilitation professionals.29,30

After implementation of all KT strategies was complete, follow-up discussion and feedback from staff was encouraged at monthly staff meetings, as regular feedback has also been used as part of successful multifaceted interventions aimed at encouraging evidence-based practice of physical therapists.31

Opinion leaders

The goals of opinion leader involvement were to address barriers such as lack of familiarity with STOM and lack of training in administration of STOM. Opinion leaders also promoted facilitators such as support of colleagues in the use of STOM. The involvement of opinion leaders has been used to encourage evidence-based practice by physical therapists28,32 and occupational therapists.29

At BIDMC, more experienced clinicians who were acting as mentors in a preexisting mentorship program33 were recruited as opinion leaders in the days and weeks following the initial educational sessions. These opinion leaders (mentors) as well as all staff clinicians (mentees) were encouraged to discuss STOM in the context of patient care as part of regular, weekly 30-minute mentoring meetings. They were also encouraged to incorporate and practice use of STOM during mentor-supervised cotreatments, which allowed for mentee practice in administration of STOM. The one-on-one meetings and cotreatments also allowed for personal feedback, which is a suggested method important for helping clinicians incorporate evidence into practice.34

Audit and feedback

Audit and feedback were the final KT strategies employed. Auditing refers to the objective measurement of clinician performance following a specific intervention aimed at behavior change. Feedback refers to the process of providing clinicians with the results of an audit. The authors performed an audit of medical records to assess the frequency of STOM use and interpretation by physical therapists in the department; these steps are described in further detail in the next section. Based on the results of this audit, potential areas for improvement were identified and all physical therapists were provided with feedback regarding their frequency of using STOM. Feedback was presented in terms of the performance of the entire department rather than individual performance. Specific clinical scenarios in which therapists were less likely to use or interpret STOM were illustrated, and staff were provided with tips to improve frequency of use and interpretation. According to a recent systematic review, audit and feedback generally leads to small, but potentially important improvements in professional practice.35

Data Sources, Searches, and Collection

Following the implementation of all KT interventions, 5 data collection periods were identified, each 7 days in duration (Fig.). The first data collection period (September 1, 2013–September 7, 2013) served as a baseline, as it occurred immediately prior to intervention. The second data collection period (May 3, 2014–May 9, 2014) was chosen because it occurred after the Inpatient Rehabilitation Services manager mandated functional reporting, yet prior to the full QI rollout. The third data collection period (October 5, 2014–October 11, 2014) was approximately 3 months following full implementation of the QI project in an effort to assess initial behavior change. Data collection period 4 (March 1, 2015–March 7, 2015) was chosen to be approximately 8 months after full implementation to assess for sustained behavior change. Finally, the fifth and last data collection period (August 2, 2015–August 8, 2015) was 2 months after audit and feedback to assess the impact of this final intervention.

The medical center's electronic provider order entry system allowed for the identification of every patient who received a physical therapist consult during each data collection period. Medical record review occurred for each patient who received a physical therapist consult and a subsequent physical therapist evaluation during any of the data collection periods. Evaluations were excluded if performed by part-time staff, by one of the authors, or by a therapist with affiliating clinical students, as the students had not participated in all educational sessions. Otherwise, all physical therapist evaluations were included, regardless of diagnosis.

A physical therapist student at Boston University was recruited to assist with data collection. A data collection form was created with explicit instructions to allow for standardization of the process. Data collected included use of STOM as well as interpretation and application of STOM in a therapist's assessment statement or goals. A STOM was counted as having been used by the therapist if it was explicitly named and if all items appeared in the examination portion of the physical therapist initial evaluation. A STOM was only counted as having been interpreted if the specific STOM was cited by name in the physical therapist's assessment statement or goals. Fifty charts were initially reviewed by the student and study authors to allow for comparison of results in order to ensure consistency. The authors found 100% agreement in data collection for these medical records. Given that no errors or difference of opinions were noted between data collectors, the student proceeded in collecting all data. Data were stored in BIDMC’s secure electronic data storage system called RedCap.

Data Analysis

Ordinal variables were summarized using medians with first and third quartiles. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the use and interpretation of STOM. Generalized estimating equation methods were applied to account for within-provider correlation, and an autoregressive correlation structure was utilized. In order to assess trends over time, the primary factor of interest was the observation period. An unadjusted model and a model adjusted for patient age and staff experience level was fit for each outcome. Patient age was categorized into 1 of 5 groups (<50, 50–64, 65–79, 80–89, and 90+ years), and physical therapist experience was categorized into groups according to BIDMC’s career ladder. This career ladder takes into account years of experience and professional accomplishments and is described further in a previously published report.35 Estimated OR with 95% confidence intervals were reported based on these models. All analyses were conducted using SAS Statistical Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Across all data collection periods, a total of 963 patient encounters were evaluated, with a similar number of evaluations occurring during each data collection period. The median age of the patients for whom evaluations were performed across all data collection periods was 69 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 57–80). The median staff-level experience of the physical therapist performing the evaluations was level 2 (IQR = 1–3).

The analysis of the primary aim of this QI effort is presented in Table 3. In the logistic regression models, the final 3 data collection periods were collapsed into 1 group given the presence of zero cells in the independent variable (in periods 4 and 5, STOM were utilized 100% of the time). The model demonstrated significant differences across data collection periods (P < .0001). As compared to period 1, the unadjusted model revealed a substantial increase in STOM use in period 2 (OR = 124.1), and an even greater increase in subsequent periods (OR = 1134.5). When patient age and staff-level experience were controlled for in the adjusted model, similar results were observed (P < .0001, OR = 160.9 for period 2 and 1803.8 for periods 3–5).

Table 3.

Standardized Tests and Outcome Measures (STOM) Use Over Timea

| Period | STOM Use | Crude OR (95% CI)b | Adjusted OR (95% CI) b ,c |

| Period 1 | 32/200 (16.0%) | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Period 2 | 189/198 (95.5%) | 124.1 (55.5–277.6) | 160.9 (58.0–446.8) |

| Period 3 | 201/204 (98.5%) | ||

| Period 4 | 198/198 (100%) | 1134.5 (143.2–8987.5)d | 1803.8 (348.6–9332.9)d |

| Period 5 | 163/163 (100%) |

aOR = odds ratio.

b P < .0001.

cAdjusted for patient age and staff experience level.

dEstimated OR for periods 3, 4, and 5 combined.

The analysis of the secondary aim is presented in Table 4. In the unadjusted model, interpretation increased monotonically over the data collection periods (P < .0003), with OR of 2.1, 16.1, 22.6, and 40.2 in periods 2 through 5, respectively. Similar results were seen in the adjusted model when controlling for patient age and staff experience.

Table 4.

Standardized Tests and Outcome Measures (STOM) Application Over Timea

| Period | STOM Application | Crude OR (95% CI) b | Adjusted OR (95% CI) b ,c |

| Period 1 | 9/200 (4.5%) | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Period 2 | 17/198 (8.6%) | 2.1 (0.8–5.5) | 2.2(0.9–5.3) |

| Period 3 | 85/204 (41.7%) | 16.1 (6.5–39.8) | 18.3 (7.3–45.9) |

| Period 4 | 97/198 (49.0%) | 22.6 (8.8–57.8) | 22.0 (8.8–54.6) |

| Period 5 | 104/163 (63.8%) | 40.2 (14.1–114.5) | 46.3 (16.1–133.5) |

aOR = odds ratio.

b P < .0003

cAdjusted for patient age and staff experience level.

Discussion

It has been suggested that the use of explicit conceptual frameworks by clinicians and researchers conducting KT interventions is associated with a range of potential benefits.36 The QI project described above fits into the theoretical framework developed by Straus and colleagues to describe the knowledge-to-action process.37

These results suggest that the significant increase in STOM use over time was associated with KT strategy interventions, rather than due to chance. It also suggests that the QI interventions were effective in achieving the primary goal of this study. Prior to the implementation of this QI effort, rates of use of STOM at BIDMC were similar to those cited in published reports.10 After the implementation of the first KT strategy manager mandate, there was a considerable increase in the use of STOM, but not in the application of STOM. However, the implementation of a more comprehensive approach utilizing a variety of KT strategies was associated with a higher frequency of interpretation and application of STOM.

The consideration of physical therapist daily workflow in clinical practice was integral to the overall success of this QI project. Following chart review and prior to evaluation, therapists had the ability to access their pocket cards, which included a list of all the patient populations in which each STOM had been validated, to help in the decision-making processes regarding the selection of the most appropriate STOM. The pocket cards also included a list of the type of psychometric data available, so the therapists could select a STOM that would be able to aid in answering a particular clinical question. During evaluations, these pocket cards also provided a reference regarding technically correct administration of the STOM. After completing the evaluation and during documentation, therapists had immediate access to the EHR templates that facilitated the interpretation and the application of the results of the STOM. Additionally, the mentors who acted as opinion leaders were available during patient care to provide support in the technically correct administration of a measure or to answer questions regarding the application of results of STOM to specific patients.

The Measures Selection Committee was also key to the success of this effort. Assuming that physical therapists would be more likely to use STOM that had relevant clinical utility in the acute care setting, the committee prioritized measures that provided information regarding: projection of discharge disposition, change in functional status over time, short- or long-term functional prognosis, and fall risk. Preference was also given to measures developed or studied specifically in the acute care setting, as well as to measures that were highly recommended for use in acute care by the APTA Evaluation Database to Guide Effectiveness (EDGE) task forces. The EDGE task force was formed in order to come to an agreement on the best outcome measures to use for certain patient populations.38

Other practical considerations regarding the selection of specific STOM included the staff's preexisting familiarity with certain measures, as well as the ease with which a therapist could administer a measure. Priority was given to measures that could be completed quickly and with minimal equipment requirements. Performance-based measures were chosen over self-report measures out of concern that for patients in acute care, self-report measures may be confusing, difficult to complete, and too time consuming.1 It was also important to consider how each measure fit into the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework. According to APTA recommendations, measurements at the level of activity and participation are the most consistent with patient-centered goals,7 therefore, most of the measures selected provide information at the level of activity and participation; the Confusion Assessment Method in the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) was the only measure utilized that provided measurement at the level of body structure and function.39

Ultimately, implementation of these KT strategies was associated with a change in practice within the inpatient physical therapy department. There were, however, a number of barriers that were encountered over the course of project implementation. One of the most important clinical barriers encountered was the difficulty some therapists had with incorporating results of STOM into complex clinical decision making. These therapists were encouraged to resist being bound to the results of any one STOM as it applied to a specific patient. Therapists were instead encouraged to qualify their clinical decisions in their assessment statements and to consider results from evidence-based STOM as only one part of clinical decision making. For example, the results of a STOM may be consistent with projected discharge to inpatient rehabilitation; however, other factors such as a patient's social supports and individual goals may lead a therapist to recommend discharge to home despite the results of the STOM.

To our knowledge, no previous reports have demonstrated a quantitative, positive association between KT strategies and the promotion of evidence-based practice in acute care physical therapy. The inclusion of a quantitative assessment of the actual frequency of STOM use is a strength of this report, especially considering prior research that has shown that health professionals substantially overestimate their actual performance in complying with the recommendations of governing agencies.40

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to these findings regarding the effectiveness of this QI project. Due to routine staff turnover, a rotating schedule with transition to different patient populations, and assignment of students over the 2-year course of the improvement effort, there was some heterogeneity of groups of physical therapists at different periods of measurement. The authors were initially concerned that this may limit comparison between groups; however, given that the authors wished to measure a desired effect on the practice of the department as a whole, the authors considered the QI project a success. Statistical analysis also accounted for the heterogeneity of groups of physical therapists at different data collection periods. In addition to use of the adjusted models to account for staff experience at each time period, analysis revealed strong serial correlation of observations within providers. This means that once a physical therapist made a behavior change and began using and interpreting a measure, they were likely to continue doing so over the course of time. This significant relationship demonstrates the exact nature of the behavior change the authors hoped to demonstrate.

The relatively limited number of STOM developed and studied in acute care populations as well as limited psychometric information for different measures, were challenges in choosing, implementing, and interpreting a measure. Lack of a control group reduced the authors’ ability to control for extraneous variables such as continuing education courses pursued by physical therapists, which could also influence the frequency of STOM use. Additionally, setting specific barriers and facilitators were not identified through clinician surveys within our department, but rather through previous published literature reviews.

In terms of the application of KT strategies, a more robust system for continual audit and feedback, including the provision of feedback based on individual performance, may have resulted in even higher levels of behavior change between periods 4 and 5. Finally, when considering data collection, the frequency of STOM interpretation and application reported may have been underestimated. A STOM was only counted as having been interpreted by the therapist if the measure was specifically cited in the assessment statement, or if a goal was written with reference to MDC/MCID.

Conclusions

The results of this QI effort are encouraging. They suggest that systematic implementation of KT strategies that are tailored to the specific needs of a practice setting is associated with an increased use and interpretation of STOM by physical therapists. Given adequate time devoted to research, development, and staff education—as well as consideration of health care funding—the implementation of the KT strategies described in this report is feasible in any acute care physical therapy department and potentially in other settings as well.

Future research should focus on the validity of using otherwise well-established STOM in the acute care setting, the impact of increasing use of STOM on patient outcomes, and the value in use of STOM for novice versus experienced clinicians. Given the financial implications for hospital length of stay in the United States, the effect of STOM use on the accuracy of initial discharge recommendations made by physical therapists should also be examined.

Author Contributions and Acknowledgments

Concept/idea/research design: B. McDonnell, S. Stillwell

Writing: B. McDonnell, S. Stillwell, S. Hart, R. Davis

Data collection: B. McDonnell, S. Stillwell, S. Hart

Data analysis: B. McDonnell, S. Stillwell, S. Hart, R. Davis

Project management: B. McDonnell, S. Stillwell

Providing participants: B. McDonnell

Providing facilities/equipment: B. McDonnell

Providing institutional liaisons: B. McDonnell

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): B. McDonnell, S. Stillwell, S. Hart, R. Davis

The authors thank all of the therapists in the inpatient rehabilitation department at BIDMC for their support during the development and implementation of this QI effort. The authors also thank Joan Drevins, PT, DPT, a board-certified cardiopulmonary clinical specialist, for her critical review of the manuscript, and Deborah Adduci, PT, clinical manager, for her support and guidance throughout this process.

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst and the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award) (ref. no. UL1 TR001102), and with financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures and Presentations

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No conflicts of interest were reported.

This manuscript is adapted in part from a presentation titled “Breaking Down Barriers: Utilization of Standardized Measures in Acute Care” at the American Physical Therapy Association's 2015 Combined Sections Meeting, Indianapolis, Indiana, February 4–7, 2015.

References

- 1. Jette DU, Bacon K, Batty C et al. . Evidence-based practice: beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2003;83:786–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Potter K, Fulk GD, Salem Y et al. . Outcome measures in neurological physical therapy practice. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2011;35:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sullivan JE, Andrews AW, Lanzino D et al. . Outcome measures in neurological physical therapy practice. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2011;35:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thier SO. Forces motivating the use of health status assessment measures in clinical settings and related clinical research. Med Care. 1992;30(5 Suppl):MS15–MS22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andrews AW, Folger SE, Norbet SE et al. . Tests and measures used by specialist physical therapists when examining patients with stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2008;32:122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK et al. . Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94:379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Physical Therapy Association Guide to physical therapist practice 3.0. Available at http://guidetoptpractice.apta.org/. Accessed January 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bland MD, Whitson M, Harris H et al. . Descriptive data analysis examining how standardized assessments are used to guide post-acute discharge recommendations for rehabilitation services after stroke. Phys Ther. 2015;95:710–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK et al. . AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1252–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jette DU, Halbert J, Iverson C et al. . Use of standardized outcome measures in physical therapist practice: perceptions and applications. Phys Ther. 2009;89:125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haigh R, Tennant A, Biering-Sørensen F et al. . The use of outcome measures in physical medicine and rehabilitation within Europe. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Peppen RP, Maissan FJ, Van Genderen FR et al. . Outcome measures in physiotherapy management of patients with stroke: a survey into self-reported use, and barriers to and facilitators for use. Physiother Res Int. 2008;13:255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manns PJ, Norton AV, Darrah J. Cross-sectional study to examine evidence-based practice skills and behaviors of physical therapy graduates: is there a knowledge-to-practice gap? Phys Ther. 2015;95:568–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swinkels RA, van Peppen RP, Wittink H et al. . Current use and barriers and facilitators for implementation of standardised measures in physical therapy in the Netherlands. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duncan EAS, Murray J. The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stevens JG, Beurskens AJ. Implementation of measurement instruments in physical therapist practice: development of a tailored strategy. Phys Ther. 2010;90:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zidarov D, Thomas A, Poissant L. Knowledge translation in physical therapy: from theory to practice. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1571–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canadian Institutes of Health Research Knowledge translation. Available at http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html. Updated July 28, 2016. Accessed January 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Menon A, Korner-Bitensky N, Kastner M et al. . Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Wees PJ, Jamtvedt G, Rebbeck T et al. . Multifaceted strategies may increase implementation of physiotherapy clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abrams D, Davidson M, Harrick J et al. . Monitoring the change: current trends in outcome measure usage in physiotherapy. Man Ther. 2006;11:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Functional reporting. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Billing/TherapyServices/Functional-Reporting.html. Accessed January 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haley SM, Coster WJ, Andres PL et al. . Activity outcome measurement for postacute care. Med Care. 2004;42(1 suppl):I49–I61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cohen ET, Potter K, Allen DD et al. . Selecting rehabilitation outcome measures for people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:181–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stevans JM, Bise CG, McGee JC et al. . Evidence-based practice implementation: case report of the evolution of a quality improvement program in a multicenter physical therapy organization. Phys Ther. 2015;95:588–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graham ID, Tetroe J. Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:936–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shields RK, Leo KC, Miller B et al. . An acute care physical therapy clinical practice database for outcomes research. Phys Ther. 1994;74:463–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rebbeck T, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Evaluating two implementation strategies for whiplash guidelines in physiotherapy: a cluster-randomised trial. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McQueen J. Practice development: bridging the research-practice divide through the appointment of a research lead. Br J Occup Ther. 2008;71:112–118. [Google Scholar]

- 30. McQueen J, Miller C, Nivison C et al. . An investigation into the use of a journal club for evidence-based practice. Int J Ther Rehab. 2006;13:311–317. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bekkering GE, Hendriks HJ, van Tulder MW et al. . Effect on the process of care of an active strategy to implement clinical guidelines on physiotherapy for low back pain: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brown CJ, Gottschalk M, Van Ness PH et al. . Changes in physical therapy providers’ use of fall prevention strategies following multicomponent behavioral change intervention. Phys Ther. 2005;85:394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carthas S, McDonnell B. The development of a physical therapy mentorship program in acute care. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2013;4:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maas MJ, van der Wees PJ, Braam C et al. . An innovative peer assessment approach to enhance guideline adherence in physical therapy: single-masked, cluster-randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2015;95:600–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S et al. . Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;13:CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hudon A, Gervais MJ, Hunt M. The contribution of conceptual frameworks to knowledge translation interventions in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2015;95:630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID. Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. American Physical Therapy Association EDGE Task Force. Recommended outcome measures. Available at http://www.ptresearch.org/article/127/resources/researchers/edge-task-force-evaluation-database-to-guide-effectiveness/recommended-outcome-measures. Accessed January 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gusmao-Flores D, Salluh JI, Chalhub RÁ et al. . The confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) and intensive care delirium screening checklist (ICDSC) for the diagnosis of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Crit Care. 2012;16:R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Peppen R, Schuurmans M, Stutterheim E et al. . Promoting the use of outcome measures by an educational programme for physiotherapists in stroke rehabilitation: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:1005–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed ‘Up & Go’: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;14:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crapo RO, Casaburi R et al. . ATS statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kalra L, Crome P. The role of prognostic scores in targeting stroke rehabilitation in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Denehy L, de Morton NA, Skinner EH et al. . A physical function test for use in the intensive care unit: validity, responsiveness, and predictive utility of the physical function ICU test (scored). Phys Ther. 2013;93:1636–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parker MJ, Palmer CR. A new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75:797–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Motor Control: Theory and Practical Applications. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR et al. . Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fritz S, Lusardi M. White paper: “walking speed: the sixth vital sign.” J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2009;32:2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC et al. . Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilson CM, Kostsuca SR, McPherson SM et al. . Preoperative 5-meter walk test as a predictor of length of stay after open heart surgery. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2015;26:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Latham N, Mehta V, Nguyen AM et al. . Performance-based or self-report measures of physical function: which should be used in clinical trials of hip fracture patients? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:2146–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Steffen T, Seney M. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change on balance and ambulation tests, the 36-item short-form health survey, and the unified Parkinson disease rating scale in people with Parkinsonism. Phys Ther. 2008;88:733–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tilson JK, Sullivan KJ, Cen SY et al. . Meaningful gait speed improvement during the first 60 days poststroke: minimal clinically important difference. Phys Ther. 2010;90:196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Watson MJ. Refining the ten-metre walking test for use with neurologically impaired people. Physiotherapy. 2002;88:386–397. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Musselman KE. Clinical significance testing in rehabilitation research: what, why, and how? Phys Ther Rev. 2007;12:287–296. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ostir GV, Berges I, Kuo YF et al. . Assessing gait speed in acutely ill older patients admitted to an acute care for elders hospital unit. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:353–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]