Abstract

Background

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is highly prevalent in older adults, leading to functional decline.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate physical activity (PA) only and PA plus cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain (CBT-P) among older adult veterans with CLBP.

Design

This study was a pilot randomized trial comparing a 12-week telephone–supported PA-only intervention group (PA group) or PA plus CBT-P intervention group (PA + CBT-P group) and a wait-list control group (WL group).

Setting

The study setting was the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

Participants

The study participants were 60 older adults with CLBP.

Interventions

The PA intervention included stretching, strengthening, and aerobic activities; CBT-P covered activity pacing, relaxation techniques, and cognitive restructuring.

Measurements

Feasibility measures included enrollment and completion metrics; acceptability was measured by completed phone calls. Primary outcomes included the Timed “Up & Go” Test and the PROMIS Health Assessment Questionnaire. Generalized linear mixed models were used to estimate changes within and between groups. Effect sizes were calculated with the Cohen d. Adverse effects were measured by self-report.

Results

The mean participant age was 70.3 years; 53% were not white, and 93% were men. Eighty-three percent of participants completed the study, and the mean number of completed phone calls was 10 (of 13). Compared with the results for the WL group, small to medium treatment effects were found for the intervention groups in the Timed “Up & Go” Test (PA group: −2.94 [95% CI = −6.24 to 0.35], effect size = −0.28; PA + CBT-P group: –3.26 [95% CI = −6.69 to 0.18], effect size = −0.31) and the PROMIS Health Assessment Questionnaire (PA group: −6.11 [95% CI = −12.85 to 0.64], effect size = −0.64; PA + CBT-P group: –4.10 [95% CI = –11.69 to 3.48], effect size = −0.43). Small treatment effects favored PA over PA + CBT-P. No adverse effects were noted.

Limitations

This was a pilot study, and a larger study is needed to verify the results.

Conclusions

This pilot trial demonstrated that home-based telephone-supported PA interventions were feasible, acceptable, and safe for older adult veterans. The results provide support for a larger trial investigating these interventions.

Low back pain (LBP) is a complex and a multidimensional condition resulting in approximately  100 to

100 to  200 billion per year in costs for the United States.1 It is particularly common among US military veterans, with 60% of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) primary care patients reporting chronic pain that significantly affects self-rated health, functional status, and self-reported quality of health care; of these, about 60% specifically report having LBP.2 Among older adults, LBP is also very common, with prevalence estimates in the general community ranging from 13% to 49% (depending on the definition of LBP and the age range of included participants).3,4 As in the civilian population,5 the prevalence of chronic LBP (CLBP), defined as pain lasting more than 3 months, is rising steadily among veterans, with a 4.8% annual increase from 2000 to 20076; this rate of increase is higher than those for diagnoses such as diabetes, hypertension, and depression.

200 billion per year in costs for the United States.1 It is particularly common among US military veterans, with 60% of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) primary care patients reporting chronic pain that significantly affects self-rated health, functional status, and self-reported quality of health care; of these, about 60% specifically report having LBP.2 Among older adults, LBP is also very common, with prevalence estimates in the general community ranging from 13% to 49% (depending on the definition of LBP and the age range of included participants).3,4 As in the civilian population,5 the prevalence of chronic LBP (CLBP), defined as pain lasting more than 3 months, is rising steadily among veterans, with a 4.8% annual increase from 2000 to 20076; this rate of increase is higher than those for diagnoses such as diabetes, hypertension, and depression.

Despite current guidelines indicating individuals with CLBP should participate in regular exercise,7 only 38% of veterans with chronic pain, including CLBP, use exercise to treat their pain.2 Among older adults, CLBP is associated with declining function over time, independent of other health conditions.8 This is particularly important because functional decline is associated with many deleterious effects, including changes in cognitive function and mortality.9,10 Physical activity (PA) is a simple intervention that can significantly improve physical function among older adults11 and can be successfully delivered in the home setting.12 Additionally, cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain (CBT-P), are associated with improved outcomes among individuals with CLBP,13 have been shown to improve functional outcomes when combined with exercise,14 and can be flexibly adapted to a wide range of clinical settings.

The use of telecommunication has come to the forefront as a novel method to deliver health care remotely. Older adults, in particular, have the potential to benefit greatly from telecommunication as a way to access medical services from the comfort of their homes.15 This area, in particular among older adults with CLBP, is greatly understudied.16 Furthermore, research on exercise and behavioral interventions to treat CLBP in older adults has been very limited.4,17 Despite older adults’ willingness to engage in self-management programs for pain that include both cognitive and PA components,18,19 we are not aware of previous studies that have utilized a home-based telephone-supported delivery approach in this demographic group. In this pilot study, we examined a home-based telephone-supported PA program, alone or in conjunction with telephone-delivered CBT-P, among older adults with CLBP.

Methods

Design Overview and Setting

The Physical Activity for Older Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain (PACe-LBP) study was a single-blind pilot feasibility trial (NCT02327325) reported using the CONSORT extension for randomized pilot studies.20 Baseline and follow-up assessments were conducted at the Durham VA Health Care System (DVAHCS) by a trained research assistant who was unaware of the research group assignment. The participants and interventionists were aware of the group assignment. Prior to baseline assessment, participants gave informed consent and received a physical examination by a licensed physical therapist. The purpose of this physical therapist examination was to determine if the participant was safe for participating in a home-based exercise program by using a combination of physical strength, balance testing, and clinical judgment. Following baseline measures participants were randomized by use of a computer-generated randomization table programmed into the study tracking database. Participants were randomized with equal allocation to 1 of 3 study arms: a group receiving PA only (PA group), a group receiving PA plus CBT-P (PA + CBT-P group), or a waitlist control group (wait-list group). Approximately 12 weeks later, participants returned to the DVAHCS for follow-up assessments. The 12-week intervention was chosen because this is a reasonable time frame for older adults to experience neuromuscular adaptations and changes in general physical function.21 We included a control group to account for any general improvement or changes that may be observed in the course of CLBP. Participants were paid  30 for each visit for time and travel.

30 for each visit for time and travel.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were eligible if they self-reported having had lower back pain on most days for greater than 3 months; were sedentary, defined as reporting less than 150 minutes of moderate PA per week; could complete a 10-second semitandem stand and walk about 2.4 meters (8 ft) in 6.0 seconds, to safely complete a home exercise program; reported that they were not satisfied with their current state of functional ability, based on reporting “dissatisfied” with at least 1 aspect of physical function on the Satisfaction With Physical Function Scale22; and could safely participate in the intervention, based on the physical therapist baseline examination and clinical expertise. The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Unilateral or bilateral sciatica; isolated coccyx pain (based on self-report at screening)

Dementia, memory loss, or other significant cognitive impairment found in the medical record

Movement or motor neuron disorders (eg, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis)

Rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or other systemic rheumatic disease

Hospitalization for a stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, or coronary artery revascularization in the past 3 months

Significant hearing impairment without accommodations (must be able to talk on the telephone)

Psychosis or current, uncontrolled substance abuse disorder

Any other health conditions determined by the study team to be contraindications to performing mild to moderate home exercises

Potential participants were identified in the DVAHCS medical record, mailed an introductory letter, and screened by telephone for inclusion in the study or referred directly to the study from within the physician providers at the DVAHCS.

Interventions

Overview

Interventions for this study were completed by the participants at their home setting, supported by telephone calls by the physical therapist and exercise counselor with a master's degree in exercise science. We chose a home-based exercise program because of its feasibility for widespread dissemination in the VA and because prior work has shown that home-based PA programs are safe and effective for improving physical function among older adults.23 We chose a telephone-based delivery approach because this method of communication has been well received by older adult veterans in our prior and ongoing work in telephone-based PA support for osteoarthritis.24–26 After the baseline evaluation and delivery of the intervention, each intervention group received 3 telephone follow-up calls from the study physical therapist, scheduled for every 4 weeks, and 10 phone calls by the exercise counselor, scheduled every week following the first physical therapist phone call at week 1. Each phone call, from both the counselor and physical therapist, took approximately 15 minutes to complete. We chose this “joint delivery” model to combine the clinical expertise of the physical therapist (eg, addressing specific functional and clinical issues and recommending appropriate modifications and progression of activity) and the motivational interviewing expertise of the exercise counselor, to foster participation. If participants reported any increased lower back pain or other clinical issues during a telephone call with the exercise counselor, the physical therapist followed up with a telephone call to address these problems. The purpose of the 3 scheduled phone calls by the physical therapist was to assess any potential issues as a result of the delivered intervention (eg, increased pain) to allow necessary modifications in the exercise program. The purpose of the 10-scheduled exercise counselor phone calls was to ask participants about their PA during the prior week; based on this the counselor helped participants to refine action plans for achieving PA goals for the upcoming week. The exercise counselor also assessed any barriers participants encountered since the last phone call. The exercise counselor also asked participants, during each phone call, to rate their self-efficacy for completing action plans with a standardized question (ie, “How confident are you that you can complete these action plans, on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being not at all confident and 10 being very confident?”). If participants rated their self-efficacy lower than 7, then the exercise counselor recommended they revise their plans so they were more confident they would be able to carry them out. A description of the weekly phone calls and information covered on those calls can be found in the Appendix (A). Adverse events were defined by protocol as any untoward physical or psychological occurrence by participating in research. Potential adverse events were collected only via self-report from the participants to study staff and were reported in accordance with VA institutional review board requirements.

Physical activity program

Participants randomized to either the PA group or the PA + CBT-P group received written instructions and pictures of exercises. We also provided participants an exercise video called Take Control With Exercise, created by the Arthritis Foundation. At the baseline visit, the physical therapist provided participants with personalized recommendations, guided by baseline assessments, including specification of the specific exercises assigned (eg, starting with a smaller number of exercises at the beginning of the program, easier options for those with more limited function) and duration/number of repetitions for each exercise. Exercise programs were based on a core set of strengthening and stretching exercises (in addition to regular aerobic activity), which covered major muscle groups and functional tasks. Examples of the choices of exercises are provided in the Appendix (B).

CBT-P intervention

In addition to the previously described PA intervention, participants in the PA + CBT-P group received instruction in CBT-P skills, woven into each telephone-based session with the exercise counselor and with specific application to PA (eg, overcoming pain-related barriers and managing pain associated with activity). This intervention was delivered by the exercise counselor, cross-trained to deliver CBT-P, as we have successfully done previously.24 Participants received written materials for instruction in each skill, as well as an audio recording to facilitate progressive muscle relaxation. The specific topics included were: activity pacing, breathing relaxation, distraction, progressive muscle relaxation, and cognitive restructuring (Appendix, C).

WL group

Participants in the WL group were instructed to continue with their current lifestyle for the next 12 weeks. They were then given the option to choose the PA-only or PA + CBT-P program following 12-week assessments.

Measures

Primary outcomes

We selected 2 primary outcomes for this study, 1 physical performance test as a direct measure of physical ability and 1 self-reported physical function measure to quantify perceived physical ability. The Timed “Up & Go” Test (TUG) is a test that requires the participants to stand from a standard arm chair, walk 3 meters, and then return to sitting in the same chair.27 The TUG has demonstrated excellent reliability and correlates well with other standard measures such as gait speed, self-report, and clinical report indices of function and is predictive of those who can safely ambulate.28 The minimal detectable change for the TUG has been reported at less than 2.0 seconds.29 The PROMIS Health Assessment Questionnaire30 is a self-report measure that captures both activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. It consists of 20-items scored on a scale from 1 to 5, with a summed 0- to 100-unit scale.

Secondary outcomes

Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) was used to measure the impact of participants CLBP-specific disability. The RMDQ with the 24-item self-report questionnaire is reliable, valid31 and responsive to LBP32 treatment. The minimal detectable change has been reported to be between 2 and 3 points.33 The Satisfaction with Physical Function Scale was used to measure participants’ overall satisfaction with their current state of physical function. This is a validated 5-item questionnaire that assesses people's satisfaction with their ability to complete basic functional tasks that are often affected by lower extremity osteoarthritis, including stair-climbing, walking, doing housework (light and heavy), lifting and carrying.22 All items are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from “very dissatisfied” (−3) to “very satisfied” (+3). The Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS) captures specific functional tasks that may be missed on standardized questionnaires. The measure consists of 5 items. Each item is scored from 0 (“unable to perform task”) to 10 (“able to complete the activity without difficulty”).34 The PSFS is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change over time with a minimal detectable change of 2 points when scores are averaged.34,35 We also implemented a measure of coping, using the Coping Strategies Questionnaire, the most commonly used measure of coping among individuals with chronic pain, whose measurement properties have been confirmed in people with a variety of pain-related conditions36,37 This scale includes 48 items that assess 6 cognitive domains (Catastrophizing, Diverting Attention, Ignoring Sensations, Coping Self-Statements, Reinterpreting Pain Sensations, Praying-Hoping) and 1 behavioral domain (Increasing Behavioral Activities). Each domain includes 6 items, and participants rate the frequency of their use of specific coping strategies on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never do that”) to 6 (“always do that”). We analyzed the Coping Strategies Questionnaire without catastrophizing to be consistent with how others examining musculoskeletal conditions have scored this scale in the literature.38,39

Participation and feasibility measures

We measured participation as the number of telephone calls completed and feasibility as the number of participants completing the study.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and disease burden

Self-reported participant characteristics included age, race/ethnicity, sex, household financial state (with low income defined as self-report of just meeting basic expenses or not having enough to meet basic expenses), education level (college vs less education), work status (disabled vs other [retired, employed part-time, or unemployed]), marital status (married vs single, divorced, widowed, or separated), and body mass index (calculated by height and weight measured at baseline). Burden of CLBP was measured with selected components from the NIH Task Force low back pain minimal dataset.40 From this data set we characterized low back pain chronicity and pain interference with the 4-item PROMIS30 pain interference questions, treatment history (surgical, pharmaceutical), and other factors affecting spine health (drug use, demographics).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics in the form of means and standard deviations and counts and proportions were used to describe baseline characteristics across study groups. Variables with sparse data across strata were collapsed (ie, employment status and marital status). General linear mixed effects models were fit with baseline and follow-up period outcomes and predictor variables included dummy coded follow-up time effect and indicator variables for the groups interacting with follow-up time.41 An unstructured covariance matrix was used to account for the within-patient correlation between the baseline and follow-up measures. Observations were not deleted because of missing follow-up data.42 The estimation procedure for our analytic technique (linear mixed models) implicitly accommodates missingness when related to prior outcome, or to other covariates included in the model42 (defined as missing at random). Model assumptions were checked using residuals. The Cohen d was calculated as an effect size using the mixed-model–based variance. Since this was a pilot study with a small sample size, even clinically relevant differences may not be reflected as statistically significant differences (eg, P < .05). Therefore, we focused our interpretation of analysis on effect sizes, The Cohen d, for the 2 intervention groups and evaluation of whether between-group differences reflect a threshold of clinical relevance. A threshold for clinical relevance was judged by whether the change from baseline to follow-up met a minimal detectable change for that measure.

Role of the Funding Source

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation and Research Development (1I21RX001569-01A1) and by the Center of Innovation for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA Health Care System. The funders had no involvement in the conduct or reporting of this pilot feasibility trial. The views of the results for this study represent those of the authors and not of the VA Health Care System.

Results

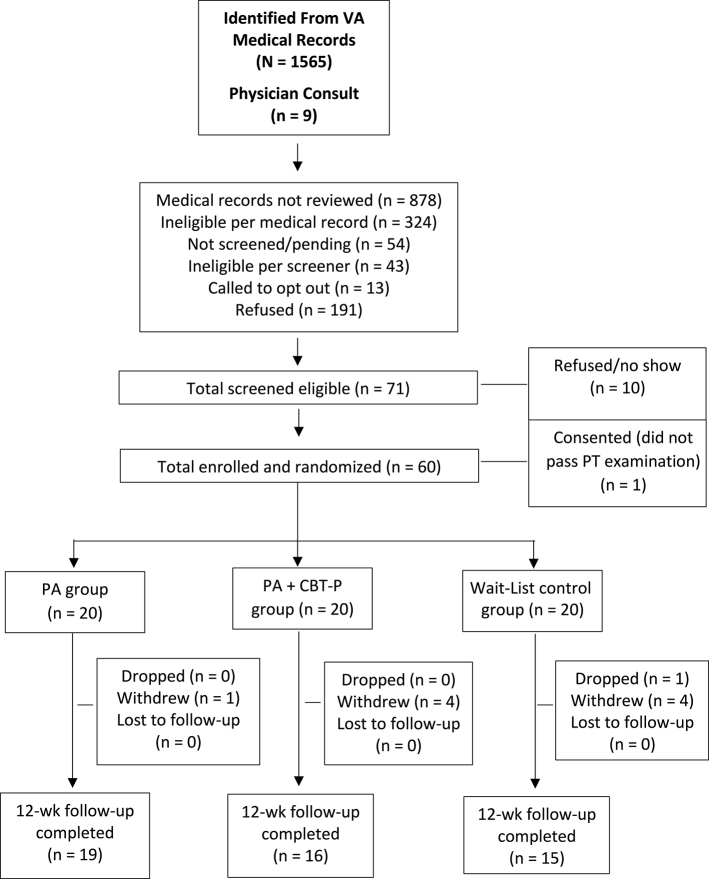

The Figure illustrates the CONSORT flow chart of participants from screening to follow-up. We reviewed 696 medical records for eligibility (identified from a data pull of VA electronic medical records, based on ICD codes for inclusion/exclusion criteria). Of these, 372 (53.4%) were determined to be eligible based on medical record review, and 366 participants were mailed an introductory letter (the remaining 6 were not sent a letter because recruitment goals were met); of these, 305 were screened by phone. The primary reasons for ineligibility at medical record review were: living too far away (n = 135), cognitive impairment (n = 27), serious/terminal illness (n = 12), and other health conditions (n = 44). The primary reasons for refusal during the telephone screening were: too busy (n = 21), not interested (n = 90), or unable to contact (n = 30). The primary reasons for ineligibility during telephone screening were: having isolated coccyx pain (n = 13), no longer having back pain (n = 15), or having chest pains in the past 2 weeks (n = 8). A total of 71 participants were deemed eligible, of which 10 refused to participate. One participant consented but did not pass the physical therapist examination for inclusion in the study because of a rapid onset of foot drop and was referred back to the primary care physician for further examination. A total of 60 older adults were randomized to a treatment group or the WL group.

Figure.

Flow chart. CBT-P = cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain, PA = physical activity, PT = physical therapist, VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Table 1 describes the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the older adult participants enrolled in the study. Table 2 describes the baseline CLBP characteristics of the participants across the 3 arms of the study. No appreciable differences were found in means or proportions between randomized groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Included Participants.a

| Variable | Summary (Total) | PA Group (n = 20) | PA + CBT-P Group (n = 20) | WL Group (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 70.3 (4.9) | 69.6 (3.5) | 69.5 (4.0) | 71.9 (6.5) |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 4 (6.7) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Men | 56 (93.3) | 19 (95.0) | 18 (90.0) | 19 (95.0) |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian | 1 (1.7) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Black/African American | 30 (50.0) | 11 (55.0) | 11 (55.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| White | 28 (46.7) | 8 (40.0) | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) |

| Missing | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 1 (1.7) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 59 (98.3) | 19 (95.0) | 20 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) |

| Education | ||||

| At least some college | 31 (51.7) | 13 (65.0) | 10 (50.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| High school or technical school | 29 (48.3) | 7 (35.0) | 10 (50.0) | 12 (60.0) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Disabled | 21 (35.0) | 7 (35.0) | 8 (40.0) | 6 (30.0) |

| Other | 39 (65.0) | 13 (65.0) | 12 (60.0) | 14 (70.0) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 38 (63.3) | 9 (45.0) | 13 (65.0) | 16 (80.0) |

| Other | 22 (36.7) | 11 (55.0) | 7 (35.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| Financial status | ||||

| Meet your basic expenses with a little left over for extras or live comfortably | 42 (70.0) | 16 (80.0) | 13 (65.0) | 13 (65.0) |

| Just meet your basic expenses or do not have enough to meet basic expenses | 16 (26.7) | 4 (20.0) | 6 (30.0) | 6 (30.0) |

| Missing | 2 (3.3) | 0.(0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) |

aValues are reported as numbers (percentages) of participants unless otherwise indicated. CBT-P = cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain, PA = physical activity, WL = wait-list control.

Table 2.

Low Back Pain Characteristics of Included Participants at Baselinea

| Variable | Summary (Total) | PA Group (n = 20) | PA + CBT-P Group (n = 20) | WL Group (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of symptoms | ||||

| 6 mo–1 y | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (10.0) |

| 1–5 y | 7 (11.7) | 3 (15.0) | 2 (10.0) | 2 (10.0) |

| >5 y | 50 (83.3) | 17 (85.0) | 17 (85.0) | 16 (80.0) |

| Duration of symptoms past 6 mo | ||||

| Half the days | 11 (18.3) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (15.0) |

| Every day or nearly every day | 46 (76.7) | 15 (75.0) | 15 (75.0) | 16 (80.0) |

| Less than half the days | 3 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Average pain, scored as 0–10 on NPR scale, in past 7 d, mean (SD) | 6.1 (1.9) | 6.3 (1.6) | 5.8 (2.1) | 6.1 (2.0) |

| Low back surgery | ||||

| No | 46 (76.7) | 15 (75.0) | 14 (70.0) | 17 (85.0) |

| Yes, 1 | 9 (15.0) | 2 (10.0) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (15.0) |

| Yes, >1 | 5 (8.3) | 3 (15.0) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Date of surgery | ||||

| <6 mo earlier | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| 1–2 y earlier | 3 (21.4) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (33.3) |

| >2 y earlier | 10 (71.4) | 4 (80.0) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (33.3) |

| Spine fusion | ||||

| Yes | 4 (28.6) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) |

| No | 9 (64.3) | 3 (60.0) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) |

| Not sure | 1 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pain interference score,b mean (SD) | 11.8 (4.2) | 13.5 (3.9) | 13.0 (4.4) | 11.9 (3.6) |

| Opioid use, yes | 41 (68.3) | 15 (75.0) | 12 (60.0) | 14 (70.0) |

| Injection therapy, yes | 21 (35.0) | 4 (20.0) | 8 (40.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Physical function score,c mean (SD) | 12.1 (3.3) | 12.3 (2.7) | 11.2 (3.8) | 12.8 (3.3) |

aValues are reported as numbers (percentages) of participants unless otherwise indicated. CBT-P = cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain, NPR = numeric pain rating, PA = physical activity, WL = wait-list control.

bFrom the 4-item PROMIS31 pain interference questions.

cFrom the 4-item PROMIS31 physical function questions.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Overall, n = 50 (83%) of participants completed 12-week follow-up assessments: 19 from the PA group, 16 from the PA + CBT-P group and 15 from the WL group. Because of the small sample size of the study we did not assess predictors of differential withdrawal or drop-out. There were no study-related adverse events. Among all participants who initiated the PA-only or PA + CBT-P program, the average numbers of intervention calls completed (out of a possible total of 13) were 10.0 (SD = 1.46) for the PA group and 8.8 (SD = 2.37) for the PA + CBT-P group. Among participants who did not withdraw before the end of the programs, the average numbers of intervention calls completed were 10.6 for the PA group and 10.4 for the PA + CBT-P group.

Primary Outcomes

Table 3 describes the within- and between-group changes for primary and secondary outcomes over 12 weeks by study arm. At 12 weeks, estimated mean TUG scores for the PA group (estimate = −2.94; 95% CI = −6.24 to 0.35) and the PA + CBT-P group (estimate = −3.26; 95% CI = −6.69 to 0.18) were improved compared with those for the WL group, with the point estimates and confidence intervals exceeding clinically relevant improvements.29 Effect sizes were in the small to medium range for both the PA group (d = −0.28) and the PA + CBT-P group (d = −0.31). There was a small difference in treatment effect, favoring PA over PA + CBT-P. At 12 weeks, estimated mean PROMIS Health Assessment Questionnaire scores for the PA group (estimate = −6.11; 95% CI = −12.85 to 0.64) and the PA + CBT-P group (estimate = −4.10; 95% CI = −11.69 to 3.48) were also improved compared with those for the WL group. The effect size for the PA group was medium (d = −0.64), and for the PA + CBT-P group it was in the small to medium range (d = −0.43), suggesting clinical usefulness in effect. When the PA group was compared with the PA + CBT-P group, the difference in treatment effect favored the PA group (estimate = −2.00; 95% CI = −9.26 to 5.26; d = −0.23).

Table 3.

Estimated Means and 95% CIs from Linear Mixed Models and Effect Sizes for Primary and Secondary Outcomesa

| Measure and Group | Mean (95% CI) for: | Effect Size (Cohen d) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Group Changes From Baseline to 12 wk | Between-Group Changes From Baseline to 12 wk | ||

| Primary outcomes | |||

| TUG | |||

| WL | 1.11 (–1.25 to 3.47) | ||

| PA | −1.84 (−4.01 to 0.33) | −2.94 (−6.24 to 0.35) | −0.28 |

| PA + CBT-P | −2.15 (−4.52 to 0.21) | −3.26 (−6.69 to 0.18) | −0.31 |

| PA vs PA + CBT-P | N/A | 0.31 (−2.99 to 3.61) | 0.04 |

| PROMIS HAQ31 | |||

| WL | 3.21 (−1.61 to 8.02) | ||

| PA | −2.90 (−7.22 to 1.43) | −6.11 (−12.85 to 0.64) | −0.64 |

| PA + CBT-P | −0.89 (−6.36 to 4.57) | −4.10 (−11.69 to 3.48) | −0.43 |

| PA vs PA + CBT-P | N/A | −2.00 (−9.26 to 5.26) | −0.23 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Satisfaction with physical function | |||

| WL | 2.96 (−0.58 to 6.49) | ||

| PA | 3.11 (−0.23 to 6.46) | 0.16 (−4.86 to 5.19) | 0.04 |

| PA + CBT-P | 3.06 (−0.68 to 6.81) | 0.11 (−7.07 to 1.07) | 0.03 |

| PA vs PA + CBT-P | N/A | 0.05 (−5.13 to 5.24) | 0.01 |

| RMDQ | |||

| WL | 0.89 (−1.11 to 2.88) | ||

| PA | −3.21 (−5.01 to −1.41) | −4.10 (−6.85 to −1.34) | −0.78 |

| PA + CBT-P | −1.11 (−3.05 to 0.83) | −1.99 (−4.85 to 0.86) | −0.41 |

| PA vs PA + CBT-P | N/A | −2.10 (−4.82 to 0.61) | −0.43 |

| PSFS | |||

| WL | 0.08 (−3.12 to 3.39) | ||

| PA | 3.72 (0.89 to 6.55) | 3.64 (−0.69 to 7.96) | 0.62 |

| PA + CBT-P | 3.00 (−0.04 to 6.04) | 2.91 (−1.55 to 7.39) | 0.50 |

| PA vs PA + CBT-P | N/A | 0.72 (−3.54 to 4.98) | 0.12 |

| CSQ without catastrophizing | |||

| WL | −5.80 (−20.10 to 8.43) | ||

| PA | 8.20 (−4.86 to 21.24) | 14.00 (−5.27 to 33.32) | 0.33 |

| PA + CBT-P | −10.70 (−24.58 to 3.10) | −4.90 (−24.74 to 14.93) | −0.12 |

| PA vs PA + CBT-P | N/A | 18.9 (11.8 to 26.0) | 0.45 |

aCBT-P = cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain, CSQ = Coping Strategies Questionnaire, HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire, N/A = not applicable, PA = physical activity, PSFS = Patient-Specific Functional Scale, RMDQ = Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, TUG = Timed “Up & Go” Test, WL = waitlist control.

Secondary Outcomes

Table 3 also provides within- and between-group differences from baseline to follow-up for secondary outcomes. Participants reported similar improvements over time in Satisfaction with Physical Function regardless of group assignment. Within-group changes on the RMDQ favored the PA and PA + CBT-P groups. A difference in the PA group versus WL group at 12 weeks was found on the RMDQ (estimate = −4.10; 95% CI = −6.85 to −1.34), with a medium to strong effect size (d = −0.78). When the PA group was compared with the PA + CBT-P group, the difference in effect favored the PA group (estimate = −2.10; 95% CI = –4.82 to 0.61; d = −0.43). These differences meet the threshold of clinically relevant improvement.33 Within-group changes for the PSFS were similar in the PA and PA + CBT-P groups. Clinically relevant improvements were found for both the PA group (estimate = 3.64; 95% CI = –0.69 to 7.96; d = 0.62) and the PA + CBT-P group (estimate = 2.91; 95% CI = −1.55 to 4.98; d = 0.50) compared with the WL group. A small difference in PSFS was found when the 2 intervention groups were compared. The treatment effects for the Coping Strategies Questionnaire without catastrophizing favored the PA group.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this single-site, pilot randomized trial was to determine the feasibility, acceptability, safety and effects of a home-based telephone-supported home exercise program for older adults with CLBP. Based upon the number of older adult veterans who completed the study, high average number of completed phone calls, and absence of any adverse events, our findings support feasibility, acceptability, and safety. Participants in both intervention groups improved in both physical performance and self-report physical function. These effects were stronger in the PA group than in the WL group, and minimal differences were found when the PA group was compared with the PA + CBT-P group. Despite our expectation that the addition of CBT-P would have an additive benefit when combined with PA, improvements were not greater in the PA + CBT-P group than in the PA group for any outcome.

We found meaningful changes between groups for some of our primary and secondary outcomes, though there were minimal differences between the PA group and the PA + CBT-P group. The medium effect sizes for both primary outcomes suggest efficacy of the intervention approaches and support the value of a larger study. We also found important changes in some of our secondary outcomes, the RMDQ and the PSFS, with differences in scores among the PA group that exceeded the reported clinically relevant changes.33,34 The improvements in these in physical function measures are important given the functional deficits among older adults with CLBP.43,44 For example, Reid et al48 found that participants with 4 months of LBP at baseline had declining gait speed, chair stands, and foot tapping over the subsequent 18 months.45 This suggests that ongoing efforts to increase and maintain physical function are important in this subgroup of older adults, and our intervention approach has potential for widespread delivery to the home setting.

We expected that older adults in the PA + CBT-P arm of the study would have improved scores above the PA group, since CBT-P has a strong evidence base for improving these outcomes in CLBP and other chronic pain conditions.46-48 In this study, older adults receiving the CBT-P intervention demonstrated somewhat similar improvements on most outcomes compared with the PA group. Others have also found that CBT-P did not have an additive effect when combined with exercise for work participation, pain disability, or coping.47 There are possible reasons that we did not observe greater improvements in the functional outcomes with the PA + CBT-P group. First, this study was a pilot study with a small sample size for each arm and may not have had a large enough sample of those participants with inadequate coping skills, who are most likely to benefit from CBT-P. Second, this group of older adults with CLBP may have responded more favorably if the intervention focused on 1 behavior change at a time. Although our findings suggest that the addition of CBT-P to PA did not confer an additional advantage, we cannot make a firm conclusion given the small sample size of this pilot study. Future studies may consider approaches to increase the intensity of the behavioral intervention with phone calls of greater duration and specific to the CBT-P intervention or further target interventions toward participants with certain characteristics, such as poor coping mechanisms, to ensure an adequate level of potential benefit from behavioral interventions.

An important consideration to the approach of our intervention is that it was delivered primarily in the home setting. Given the large number of older adult veterans with CLBP, a telephone-supported PA program could be a practical mechanism to improve physical function in this vulnerable group. Our method to utilize an exercise counselor to complement the expertise of a physical therapist may also be of high relevance given the demands for physical therapy in the VA. Our approach of using an exercise counselor and a telephone-based home exercise program may also lower costs in comparison with multiple in-person visits with a physical therapist. Future studies are needed to assess the potential cost effectiveness of this approach versus standard care. In addition, the telephone-based approach may be particularly useful to expand access for more rural VA facilities and for veterans who live greater distances from their VA.

Our study is not without limitations. First, this study was a pilot study and was not powered to detect statistical significance. Second, withdrawal from the CBT-P group was higher than that from the PA group. However, we are unable to quantitatively assess predictors of differential dropout because of our small within-group sample size. Therefore, we are unable to make inferences about whether the intervention component (CBT-P) resulted in dropout. Third, this study was conducted in 1 site and in the VA population. While there are similarities in veterans and civilians with respect to CLBP, the health care process and treatment approach differs from VA site-to-site, as well as between VA and non-VA settings. Therefore, these results may not be generalizable to the civilian population or across the VA health care system.

In this pilot study, we found that a single in-person visit with a physical therapist and a home-based exercise program with telephone support was feasible, safe, and acceptable and produced meaningful improvements in multiple outcomes among older adults with CLBP. These findings are preliminary, and a larger clinical trial is needed to fully assess the effectiveness of the interventions examined in this study.

Author Contributions and Acknowledgments

Concept/idea/research design: A.P. Goode, S.N. Hastings, K.D. Allen

Writing: A.P. Goode, Stark Taylor, S.N. Hastings, K.D. Allen, C.J. Coffman

Data collection: A.P. Goode, Stark Taylor, C. Stanwyck, K.D. Allen

Data analysis: A.P. Goode, C.J. Coffman

Project management: A.P. Goode, Stark Taylor, C. Stanwyck, K.D. Allen

Fund procurement: A.P. Goode, K.D. Allen, S.N. Hastings

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): A.P. Goode, Stark Taylor, S.N. Hastings, C. Stanwyck, C.J. Coffman, K.D. Allen

The primary author was supported by the Foundation for Physical Therapy's Center of Excellence in Physical Therapy Health Services and Health Policy Research and Training Grant. The primary author also receives funds from the NIH Loan Repayment Program, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (1-L30-AR057661-01).

Ethics Approval

Both the Durham VA Health Care System Institutional Review Board and the Duke University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation and Research Development (1I21RX001569-01A1) and by the Center of Innovation for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13–410) at the Durham VA Health Care System.

Clinical Trial Registration

This trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov [ref. no. NCT02327325, “Physical Activity for Older Adult Veterans With Chronic Low Back Pain (PACe-LBP)”].

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. S. Taylor reported employment/money received from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development. All authors report that they have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could potentially and inappropriately bias their work and conclusions.

Appendix.

A. Description of Weeks, Caller, Activities, and Modules for Telephone Calls for Both PA Group and PA Plus CBT-P Groupa

| Week | Caller | Activities/Modules |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exercise counselor | Introduction to intervention and materials Introduction to chronic low back pain, function, and gate theory of pain Information for exercise or healthy eating (participant choice) Cognitive or behavioral strategy: activity pacing discussion 1 Goal setting |

| 1 | Physical therapist | Exercise and activity goal review Review of strengthening, stretching, and aerobic exercise program Address specific functional and clinical issues Recommend appropriate modification and activity progression Review of goals set at baseline examination |

| 2 | Exercise counselor | Information for exercise or healthy eating (participant choice) Cognitive or behavioral strategy: activity pacing discussion 2 Goal setting and review |

| 3 | Exercise counselor | Information for exercise or healthy eating (participant choice) Cognitive or behavioral strategy: breathing relaxation discussion 1 Goal setting and review |

| 4 | Physical therapist | Exercise and activity goal review Review of strengthening, stretching, and aerobic exercise program Address specific functional and clinical issues Recommend appropriate modification and activity progression Goal setting |

| 5 | Exercise counselor | Information for exercise or healthy eating Cognitive or behavioral strategy: breathing relaxation discussion 2 Goal setting and review |

| 6 | Exercise counselor | Information for exercise or healthy eating Cognitive or behavioral strategy: distraction discussion 1 Goal setting and review |

| 7 | Exercise counselor | Information for exercise or healthy eating Cognitive or behavioral strategy: distraction discussion 2 Goal setting and review |

| 8 | Exercise counselor | Cognitive or behavioral strategy: progressive muscle relaxation discussion 1 Goal setting and review |

| 9 | Physical therapist | Exercise and activity goal review Review of strengthening, stretching, and aerobic exercise program Address specific functional and clinical issues Recommend appropriate modification and activity progression Goal setting |

| 10 | Exercise counselor | Cognitive or behavioral strategy: progressive muscle relaxation discussion 2 Goal setting and review |

| 11 | Exercise counselor | Cognitive or behavioral strategy: cognitive restructuring discussion 1 Goal setting and review |

| 12 | Exercise counselor | Cognitive or behavioral strategy: cognitive restructuring discussion 2 Goal setting and review |

aCBT-P = cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain, PA = physical activity.

B. Exercise Options Presented to Participants in PA Group and PA Plus CBT-P Group and Tailored to Goals and Physical Examination Findingsa

| Flexibility | Aerobic | Strengthening |

|---|---|---|

| Quadriceps stretch | Walking | Minisquat |

| Calf stretch | Swimming | Chair stands |

| Hamstring stretch | Cycling | Heel raises |

| Low back stretch | Yoga | Hip abduction |

| Hip flexor stretch | Exercise video | Step-ups |

| Core stabilization abdominal contraction | ||

| Core stabilization pelvic tilt with alternating hip flexion |

aCBT-P = cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain, PA = physical activity.

C. Overview of CBT-P Skills Taught by the Exercise Counselor to Participants in the PA Plus CBT-P Groupa

| CBT-P Skill | Description |

|---|---|

| Activity pacing | Pacing physical activity to reduce load on the body, eg, going through normal daily activities more slowly, taking rest periods, and breaking up activities into smaller tasks |

| Breathing relaxation | Involves deep, slow, rhythmic breathing to reduce bodily tension, arousal, and anxiety |

| Distraction | Involves changing the focus of attention when pain is experienced or in anticipation of a painful experience; most useful during short, discrete tasks |

| Progressive muscle relaxation | Involves systematically tensing and relaxing each muscle group in order to produce deep relaxation and reduce muscle tension |

| Cognitive restructuring | Involves identifying and reframing negative thought patterns, which may be associated with maladaptive behaviors and emotional responses as well as greater pain |

aCBT-P = cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain, PA = physical activity.

References

- 1. Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 2):21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Butchart A, Kerr EA, Heisler M, Piette JD, Krein SL. Experience and management of chronic pain among patients with other complex chronic conditions. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knauer SR, Freburger JK, Carey TS. Chronic low back pain among older adults: a population-based perspective. J Aging Health. 2010;22:1213–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bressler HB, Keyes WJ, Rochon PA, Badley E. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly: a systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1813–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP et al. . The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sinnott P, Wagner TH. Low back pain in VA users. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1338–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choi BK, Verbeek JH, Tam WW, Jiang JY. Exercises for prevention of recurrences of low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooper JK, Kohlmann T, Michael JA, Haffer SC, Stevic M. Health outcomes: new quality measure for Medicare. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hogan DB, Ebly EM, Fung TS. Disease, disability, and age in cognitively intact seniors: results from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M77–M82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leveille SG, Penninx BW, Melzer D, Izmirlian G, Guralnik JM. Sex differences in the prevalence of mobility disability in old age: the dynamics of incidence, recovery, and mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55:S41–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kelley G, Kelley KS, Hootman JM, Jones DL. Exercise and health-related quality of life in older community-dwelling adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;29:369–394. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Opdenacker J, Delecluse C, Boen F. A 2-year follow-up of a lifestyle physical activity versus a structured exercise intervention in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1602–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW et al. . Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smeets RJ, Vlaeyen JW, Hidding A et al. . Active rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cognitive-behavioral, physical, or both? First direct post-treatment results from a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN22714229]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Narasimha S, Agnisarman S, Chalil Madathil K, Gramopadhye A, McElligott JT. Designing home-based telemedicine systems for the geriatric population: an empirical study. Telemed J E Health. 2017July 31 [E-pub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dario AB, Moreti Cabral A, Almeida L et al. . Effectiveness of telehealth-based interventions in the management of non-specific low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Spine J. 2017;17:1342–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hartvigsen J, Frederiksen H, Christensen K. Back and neck pain in seniors: prevalence and impact. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:802–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Austrian JS, Kerns RD, Reid MC. Perceived barriers to trying self-management approaches for chronic pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:856–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Townley S, Papaleontiou M, Amanfo L et al. . Preparing to implement a self-management program for back pain in New York City senior centers: what do prospective consumers think? Pain Med. 2010;11:405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ et al. . CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee AH, Jancey J, Howat P, Burke L, Kerr DA, Shilton T. Effectiveness of a home-based postal and telephone physical activity and nutrition pilot program for seniors. J Obes. 2011;2011:786827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katula JA, Rejeski WJ, Wickley KL, Berry MJ. Perceived difficulty, importance, and satisfaction with physical function in COPD patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, Minder CE, Beck JC. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287:1022–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Allen KD, Bosworth HB, Brock DS et al. . Patient and provider interventions for managing osteoarthritis in primary care: protocols for two randomized controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Allen KD, Oddone EZ, Coffman CJ et al. . Telephone-based self-management of osteoarthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allen KD, Yancy WS Jr, Bosworth HB et al. . A combined patient and provider intervention for management of osteoarthritis in veterans: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wall JC, Bell C, Campbell S, Davis J. The Timed Get-up-and-Go test revisited: measurement of the component tasks. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37:109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The Timed Up & Go: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alghadir A, Anwer S, Brismée JM. The reliability and minimal detectable change of Timed Up and Go test in individuals with grade 1–3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fries JF, Cella D, Rose M, Krishnan E, Bruce B. Progress in assessing physical function in arthritis: PROMIS short forms and computerized adaptive testing. J Rheumotol. 2009;36:2061–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2000;25:3115–3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hsieh CY, Phillips RB, Adams AH, Pope MH. Functional outcomes of low back pain: comparison of four treatment groups in a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1992;15:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bombardier C, Hayden J, Beaton DE. Minimal clinically important difference: low back pain—outcome measures. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:431–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stratford P, Gill C, Westaway M, Binkley J. Assessing disability and change on individual patients: a report of a patient specific measure. Physiother Can. 1995;47:258–263. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chatman AB, Hyams SP, Neel JM et al. . The Patient-Specific Functional Scale: measurement properties in patients with knee dysfunction. Phys Ther. 1997;77:820–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hastie BA, Riley JL III, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in pain coping: factor structure of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire and Coping Strategies Questionnaire-Revised. J Pain. 2004;5:304–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bennell KL, Nelligan R, Dobson F et al. . Effectiveness of an internet-delivered exercise and pain-coping skills training intervention for persons with chronic knee pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D et al. . Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of osteoarthritic knee pain. Arthritis Care Res. 1996;9:279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D et al. . Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine J. 2014;14:1375–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu GF, Lu K, Mogg R, Mallick M, Mehrotra DV. Should baseline be a covariate or dependent variable in analyses of change from baseline in clinical trials? Stat Med. 2009;28:2509–2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weiner DK, Haggerty CL, Kritchevsky SB et al. . How does low back pain impact physical function in independent, well-functioning older adults? Evidence from the Health ABC Cohort and implications for the future. Pain Med. 2003;4:311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Edmond SL, Felson DT. Function and back symptoms in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1702–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reid MC, Williams CS, Gill TM. Back pain and decline in lower extremity physical function among community-dwelling older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sveinsdottir V, Eriksen HR, Reme SE. Assessing the role of cognitive behavioral therapy in the management of chronic nonspecific back pain. J Pain Res. 2012;5:371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol. 2014;69:153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bennell KL, Ahamed Y, Jull G et al. . Physical therapist-delivered pain coping skills training and exercise for knee osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:590–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]