Abstract

MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites were synthesized in different ratios of MgAC-Fe3O4 and TiO2 precursor. X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF), electron spin resonance spectrometry (ESR), Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET), photoluminescence (PL), and UV photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) were used to characterize the nanocomposites. The increase of MgAC-Fe3O4, in the hybrid nanocomposites’ core-shell structure, led to the decrease of anatase TiO2 peaks, thus reducing the photo-Fenton and photocatalytic activities. According to the obtained data, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 showed the best photo-Fenton and photocatalytic activities, having removed ~93% of MB (photo-Fenton reaction) and ~80% of phenol (photocatalytic reaction) after 20 and 80 mins, respectively. On the pilot scale (30 L), MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 was completely removed after 27 and 30 hours by the photo-Fenton and photocatalytic activities, respectively. The synergistic effect gained from the combined photo-Fenton and photocatalytic activities of Fe3O4 and TiO2, respectively, was credited for the performances of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites.

Subject terms: Photocatalysis, Photocatalysis

Introduction

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) including O3/H2O2, UV/O3, UV/H2O2, H2O2/Fe2+ and UV/TiO2 have been utilized for removal of toxic organic compounds in water/waste water, air, and soil. AOPs produce hydroxyl radicals that contain powerful oxidants capable of oxidizing various organic compounds with one or many double bonds1. Recently, the potential of photocatalytic materials has been extended to other applications such as photocorrosion inhibition, solar water splitting by combined with different materials2–4. Among AOPs materials, photocatalysis with TiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) under UV/Visible light has attracted keen interest from the time of its first discovery by Frank and Bard5, specifically due to its high oxidative power and chemical stability6–8. However, the limitation of TiO2 NPs is their low quantum efficiency of photo-generated electron-hole pairs caused by a high and rapid recombination rate9. For example, Degussa P25, a well-known commercial product, can reduce only 14% of phenol at 365 nm in water10. Another major disadvantage of TiO2 NPs is that they cannot be recycled post-reaction. Leakages of photocatalytic materials to aqueous solution, moreover, can lead to secondary pollution. These disadvantages can be overcome by coating TiO2 NPs on the surfaces of magnetic components such as Fe3O4 NPs, which can be easily collected from solutions under magnetic fields11.

Fe3O4 NPs have attracted interest due to their considerable magnetic behavior and strong pin polarization12. Many methods of Fe3O4-TiO2 composite synthesis, such as sol-gel, co-precipitation, hydrothermal, sonochemical, and templates routes, have been reported in the literature12,13. Incorporation of Fe3O4 NPs into a TiO2 matrix can block NP aggregation and improve the durability of catalysts14,15. However, due to the small band gap of Fe3O4 NPs (0.1 eV), Fe3O4-TiO2 composites will increase the rate of electron-hole pairs recombination, with the result that photocatalysis is usually unchanged or even diminished relative to pure TiO2 NPs12. To overcome this problem, Zheng et al. demonstrated that special structures such as core-shell microspheres in Fe3O4-TiO2 composites can delay the recombination of photo-induced electrons12; other researchers have used noble metal (Au or Ag) or rare elements (e.g. Eu) as electron traps to enhance electron-hole separation and facilitate electron excitation by creating a local hole in the electrical field13,16,17. In contrast, He et al., after preparing Fe3O4-TiO2 core-shell NPs, indicated that Fe3+ released from Fe3O4 can be doped into TiO2 NPs to decrease electron-hole pair recombination and thus increase the photocatalytic performance of Fe3O4-TiO2 core-shell NPs under visible light18. One remarkable report in this research field is that of Sun et al., who found that a small number Fe3O4 NPs loaded onto TiO2 NPs (Fe/TiO2 ratio: 1/200) could enhance the degradation of organic dye (Reactive Brilliant Red X3B). They attributed the improved photocatalytic performance of Fe3O4-TiO2 to the synergistic contribution of the photocatalytic and Fenton reactions in the composite19.

2-D materials have been attracted and extended their applications due to their unique properties20. Photocatalytic materials have also been developed based on 2-D materials such as graphene21.

From its first introduction by Mann et al., magnesium aminoclay (MgAC), which is also another types of 2-D materials, has attracted interest in its propylamine functionalities, structures, and high dispersity in water22–24. Use of MgAC’s high adsorption utility for heavy metal and organic dye removal has been reported25. Besides being utilized as a single agent, MgAC has been conjugated with other materials for environmental-treatment purposes. For example, MgAC has been coated with nZVI for removal of perfluorinated compounds26 and chromium27.

In previous work, we conjugated MgAC with TiO2 NPs and Fe3O4 NPs by different methods for environmental-treatment28,29 and microalgae-harvesting purposes30,31. The presence of MgAC in composites was demonstrated to improve the photocatalytic behavior of pure TiO2 NPs28 as well as the photo-Fenton behavior of Fe3O4 NPs29. Based on these successful preliminary results, in the present study, we synthesized MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid composites in order to exploit the advantages of both Fe3O4 and TiO2 in environmental-treatment applications.

Results and Discussion

Photo-Fenton performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on batch scale

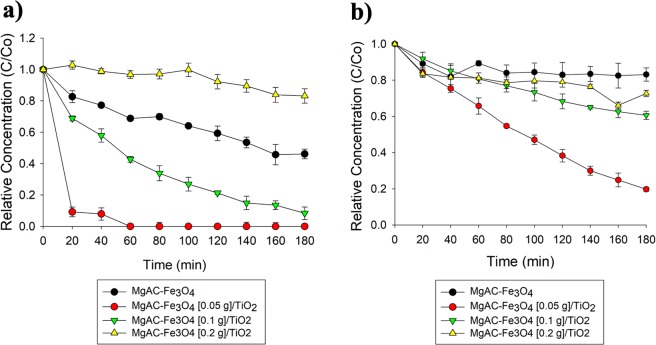

Among different MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on the batch scale, the MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 sample showed the best photo-Fenton performance, more than ~93% of MB having been removed after 20 min at a constant rate of ~0.1175 min−1; this was ~10 and ~100 times higher than the performances of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2 and MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2, which removed ~92 and ~17% of MB from aqueous solution after 180 min of reaction, respectively (Fig. 1a and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Photo-Fenton (MB, a) and photocatalytic performances (phenol, b) of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on batch scale.

Table 1.

Degradation rates of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites by photo-Fenton and photocatalytic reaction on batch scale.

| Sample | Photo-Fenton constant rate against MB 10 ppm (min−1) |

Photocatalytic constant rate against phenol 5 ppm (min−1) |

|---|---|---|

| MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 | 0.1175 | 0.0039 |

| MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2 | 0.0130 | 0.0012 |

| MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2 | 0.0011 | 0.0006 |

We chose the MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 sample to investigate the photo-Fenton performance when inhibition agents such as humic acid (HA), SO42−, and HCO3− existed in the aqueous solution. Among these three inhibition agents, SO42− and HCO3− had stronger inhibitory effects on the photo-Fenton reactions of the hybrid samples than HA, especially when these anionic and organic substances were presence at high concentrations in water (Fig. S2). The presence of HA, SO42−, and HCO3− can limit the photo-Fenton reaction of hybrid samples by reacting with generated reactive oxygen species (ROS)32.

Photocatalytic performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on batch scale

Instead of MB, we chose phenol to investigate the photocatalytic performances of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on the batch scale. Phenol is widely utilized in wastewater treatment within various industrial fields such as resins, petrochemicals, paints, textiles, oil refineries, foods, photographic chemicals, antioxidants and flavoring agents33. Phenol is a highly toxic pollutant that can cause environmental degradation and serious health problems in humans.

Among the samples, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 showed the best photocatalytic activity, ~80% of phenol having been removed after 180 min at a constant rate of 0.0039 min−1; MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2 and MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2, by comparison, had removed only 40 and 27% of phenol, respectively (Fig. 1b and Table 1). The photocatalytic activities of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites were attributed to the synergistic contributions of the photocatalytic and Fenton reactions in the hybrid nanocomposites19. In previous studies, Sun et al. indicated that increased Fe3O4 NP number could lead to decreased photocatalytic activity. Excess loading of Fe3O4 NPs promotes cluster aggregation, reduces O2 adsorption, and thereby decreases the efficiency of interfacial charge transfer for pollutant degradation19.

After 5 times recycle, the MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 sample still remained ~80% of its initial removal efficiencies against phenol (Fig. S3). The deactivation of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 could be explained by the accumulation of phenol intermediate products on actives sites of hybrid nanocomposites34. The presence of these intermediate products in the reactor after stopping photocatalytic reaction could be supported by results of TOC below35. The hybrid nanocomposites could not be regenerated by using simple washing methods34. In the future works, the more suitable regeneration methods should be considered to improve the recycling performances.

Photo-fenton and photocatalytic mechanisms

The photocatalytic mechanism of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 was attributed to the presence of anatase TiO2 in the samples, as follows:

OH• and •O2−, which are produced through the above chain reactions, will degrade pollutant molecules via oxidation and a reduction reaction process, respectively. To investigate the contribution of these ROS to the photocatalytic activity of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2, different scavengers have been used: isopropanol for •OH, methanol for both h+ and •OH, and p-benzoquinone for •O2− 36,37. In our system, highly reactive •OH was the main actor in the degradation of the pollutant materials, rather than the valence band h+ and the conductive band e− (Fig. S4)36.

On the other hand, the photo-Fenton activities of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites were extremely high, due to the presence of H2O2 in the reaction:

As noted just above, pollutants are degraded mainly by •OH, which is generated in a photo-Fenton-like process: direct photolysis of H2O2, and photocatalytic oxidation of adsorbed H2O through holes in the valence band of the TiO2 surface. Additionally, photo-induced electrons generated from TiO2 can cause reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ 38. The photocatalytic and photo-Fenton activities of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites can be additionally supported by the presence of MgAC, which, with its high adsorption utility, can bring reactants to the surfaces of photo-Fenton agents24,25.

Photoluminescence spectra could be used to explain the photocatalytic mechanism39. From photoluminescence spectra (Fig. S5), it is clearly seen that, due to the presence of TiO2 in the hybrid composites, the separated electron and holes were kept longer in excited state than original MgAC-Fe3O4 samples40,41. These results also were used to support the photocatalytic mechanisms of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites. In addition, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 have the lowest photoluminescence intensity.

Preliminary evaluation of photocatalytic and photo-Fenton performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on pilot scale

The photocatalytic activities of TiO2 NP materials have been widely investigated on the batch scale. However, for the purposes of industrial application, these materials need to be up-scaled to pilot-scale reactors. There are a variety of pilot reactors that have been introduced in the literature26,27. In this study, we used a design of pilot reactor that has been introduced in previous reports28,29. The design and photos of the pilot reactor are presented in Fig. S6.

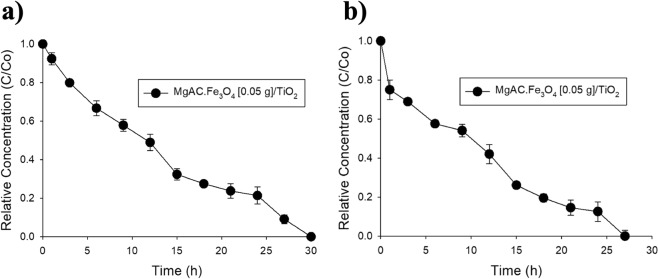

Based on the batch-scale results discussed above, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 was mass produced for testing of photocatalytic and photo-Fenton performances on the pilot scale. For photocatalytic performance testing, 30 g of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 was added to the 30 L pilot reactor to obtain a dosage of 1 g/L (similarly to the batch-scale study). After 30 hours, phenol had been nearly completely removed from the aqueous solution at a constant rate of 0.032 (h−1) (Fig. 2a and Table 2). The extended reaction time might be attributable to the heaviness of the materials, which is quickly self-precipitated. However, this phenomenon makes MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 easily recoverable after the reaction. In this study, ~80% of the materials was recovered from the reactor by simply stopping the reactor and allowing self-precipitation to occur for 24 hours without any external force (Fig. S7). To shorten the reaction time, we added 50 mL of H2O2 to obtain ~15 ppm peroxide in the reactor while reducing the dosage of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 from 1 g/L to 0.5 g/L. Under this photo-Fenton condition, phenol was completely removed after 27 hours at a constant rate of increase to 0.036 (h−1) (Fig. 2b and Table 2). It should be noted that in this paper, we present just the preliminary results; the optimal concentrations of photocatalytic materials and H2O2 should be discussed in future work investigating the effect of tap water on degradation rate. There is also a requirement for continual reactor upgrading to prevent quick sedimentation in the photocatalytic reaction and, thereby, improve the performance of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 on the pilot scale.

Figure 2.

(a) Photocatalytic and (b) photo-Fenton performances of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on pilot scale.

Table 2.

Phenol-degradation rates of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites by photocatalytic and photo-Fenton reaction on pilot scale.

| MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 | Constant rate (h−1) |

|---|---|

| Photocatalytic | 0.0032 |

| Photo-Fenton | 0.0036 |

For phenol of 500 ppm, after 48 h exposure, the LC50 was 6.39 mg/L (5.36–7.53, 95% CI). At the concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, and 20 ppm, the mortality rates were 0, 15, 20, 50, 80, and 100%, respectively (Fig. S1b). Meanwhile, the treated samples showed a mortality rate of ~10% (Fig. S1c). We suspected that the remnant toxicity had come from the leakage of Fe3+ ions from the hybrid nanocomposites or the phenol intermediate products after the reactions. So, we conducted both ICP and TOC experiments to investigate the reason behind the toxicity of the treated samples. The ICP results showed that the leakage of iron ions after stoppage of the reaction was negligible (~60 ppb after treatment, lower than the standard 300 ppb for drinking water according to the WHO)42. However, the TOC experiments showed that the organic carbon concentration was still very high after the reaction (~50–55%); thus, the toxicity could be attributed to the residual toxic phenol intermediate products (Fig. S8). Therefore, it is necessary to extend the reaction until intermediate products are completely removed, not to the phenol concentration of zero36.

Characterization of hybrid nanocomposites

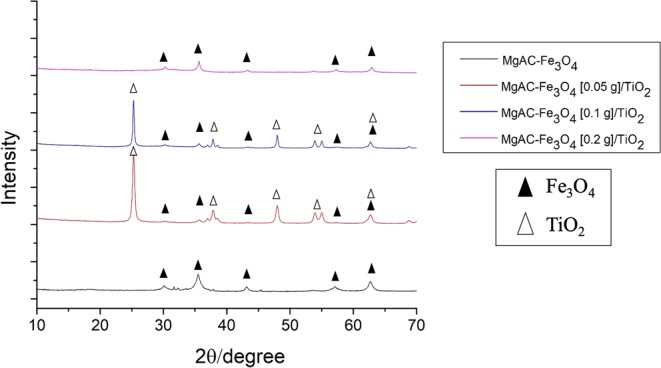

The magnetic properties of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites were preserved after the synthesis process (Fig. S9). The XRD pattern showed that, for the MgAC-Fe3O4 sample, the peaks at 29.98°, 35.5°, 42.9°, 56.7°, and 62° belonged respectively to (200), (311), (400), (511), and (440) of Fe3O4 magnetite (JCDS 00-021-1272; JCDS: Joint Committee on Power Diffraction Standard)28; meanwhile, for MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 and MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2, besides the reduced MgAC-Fe3O4 peaks, there were additional peaks at 25.5°, 37.8°, 48.3°, 54.2°, and 62.8° belonging respectively to the (101), (004), (200), (105), and (204) planes of the anatase phase (JCDS 00-064-0863, Fig. 3)28. It was apparent that, for MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2, the high-intensity peaks of TiO2 were reduced, whereas those of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2 had totally disappeared. It could be concluded that the excess MgAC-Fe3O4 loading inhibited the growth of anatase TiO2 in the hybrid nanocomposites. XRD was double checked by conducting two measurement to confirm the phenomena (Fig. S10). These results were similar with Sun et al.19. Also, the XPS analysis showed that, for MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2, besides the peaks at ~532, ~285, ~102, and ~52 eV belonging respectively to O 1 s, C1s, Si 2p, and Mg 2p (Fig. S11a)27,43, there were additional peaks at ~463 eV and ~457 eV that were attributed to the Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2 of Ti4+ states of stoichiometric TiO2, respectively (Fig. S11b)44. The Fe 2p1/2 and Fe 2p3/2 peaks of Fe3O4 existed at ~723.9 and ~710.2 eV, respectively (Fig. S11c)45.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of MgAC-Fe3O4 and MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites.

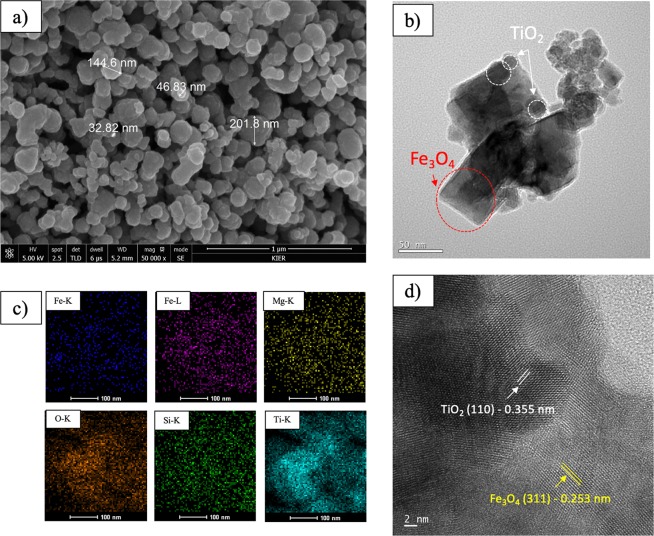

According to the SEM results, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 had an aggregated form, with a diameter ranging between 32.82 and 201.80 nm (Fig. 4a). The morphology of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 was further investigated by TEM and energy-dispersive X-ray mapping analysis (EDX). In the XRD, TEM, and EDX results, where MgAC-Fe3O4 was uniformly distributed in the TiO2 matrix, MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 showed a core-shell-like structure, MgAC-Fe3O4 playing the role as the core material and TiO2 that of the out-layer material (Fig. 4b,c). Lattice fringe spacing of 0.253 nm, belonging to the (311) plane of the Fe3O4 NPs, and 0.355 nm of TiO2 NPs in HR-TEM image confirmed the presence of these particles in the hybrid nanocomposites (Fig. 4d)46,47. From the XRF analysis results, the ratios between Fe3O4 and TiO2 were ~1:12, 1:5.5, and 1:3.5 for MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2, and MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2, respectively (Table S1). XRF and XRD confirmed the effects of MgAC-Fe3O4 loading on the photocatalytic activities of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites. Sun (2018) indicated that a ratio between Fe and TiO2 of 1:200 could enhance the degradation of organic dye, increase the loading amount of Fe3O4 and, thus, decrease the photocalytic activity19. The amounts of MgO and SiO in the XRF analysis and of Mg, Si in the EDX mapping analysis were attributed to the presence of amorphous MgAC in the hybrid nanocomposites (Fig. 5c and Table S1).

Figure 4.

Morphology of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposite. (a) SEM, (b) TEM, (c) EDX mapping analysis, and (d) HRTEM.

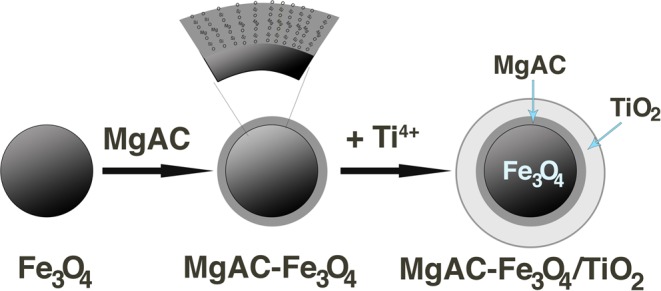

Figure 5.

Scheme of process of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 synthesis.

As for the ESR spectrum, the two main signals at ~2.0 and ~4.3 could be assigned to different Fe(III) sites48. The broad signal at ~2.0 could be assigned to the interaction between iron (octahedral sites) and MgAC. This band could belong to the chain -O-Si-O-Fe-O-Si-O- from the reaction between the MgAC and Fe3O4 NPs49. The second signal at g ~4.3 corresponded to the strongly orthorhombic sites located on the surface or to the isolated Fe(III) ions dispersed in the silica matrix50. Additionally, the symmetric broad band at g ~2.0 confirmed the ferromagnetic properties of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites (Fig. S12)49. Based on the characteristic data, the suggested structure of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 is provided in Fig. 5. In the synthesis of MgAC-Fe3O4, the presence of amino groups in the layered MgAC structure makes for high dispersibility in water25. The formation of the NH3+ and –OH groups on the surfaces of Fe3O4 NPs helps them to connect through strong electrostatic interaction. When the calcine process was carried out, besides the decomposition of amine groups on the surface material, there was evident formation of new bond bridges such as (-Fe-O-C3-Si-O-Mg-O-Si-O-C3-) within the architecture. (-C3-O-Si-Mg-O-Si-O-C3-) bridges within MgAC, for example, are very stable under harsh conditions. The large-interface surface area between Fe3O4 and MgAC facilitates formation of new bridges between Fe3O4 and MgAC at high temperature. This formation of new bridges suggests possible coordination of the O elements with the carbon elements and replacement of the O atoms in the NH3 groups51. Fe3O4 NPs are not easy to coat with TiO2 NPs layers, and so the presence of SiO2 could overcome this problem52,53. Moreover, the SiO2 layer formed in hybrid NPs can make space for the adsorption of polluted materials53,54. For synthesis of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2, adding TiO2 to the surfaces of synthetic material not only leads to increased photocatalytic activity but also forms a stable inter-connection. We offered some great bridges at the interface of the TiO2 NPs and Fe3O4, such as (-O-Ti-O-Fe-O-Si-O-Mg-O-Si-O-Fe-O-Ti-O-) or (-O-Ti-O-Si-O-Mg-O-Si-O-Ti-O-). Based on the synthetic condition, it was clearly seen that many O atoms existing on the material surface could have resulted in the development of these new bridges. Besides, Si atoms are more electronegative and less polarizable than Fe and Ti atoms; the effective positive charge on Fe and Ti is increased, and the effective negative charge on O is decreased. In other words, the electron density around Fe and Ti atoms is decreased and the shielding effect is weakened, which results in increased binding energy.

From the obtained UPS spectra (Fig. S13), the work functions were calculated to 2.98, 1.87, 2.1, 1.95, and 1.56 eV for MgAC-Fe3O4, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2, and MgAC-TiO2, respectively (Table S2). It was noted that MgAC-TiO2 was synthesized by using MgAC and titanium butoxide (TB) as precursors in ethanol media, as previously reported28. The decrease of work function could facilitate electron emission and narrow the energy band gap55. It was clearly seen that the work function of MgAC-Fe3O4 was lower than that of Fe3O4, which is around 3.7 eV in the literature56; this reduction of work function could be explained by the higher photo-Fenton activity of MgAC-Fe3O4 than that of commercial Fe3O4, as was demonstrated in a previous report29. The presence of TiO2 on the surface of MgAC-Fe3O4 continued to decrease the work function, the lowest number belonging to MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 (1.87 eV, optimal sample), which was yet larger than that of MgAC-TiO2 (1.56 eV), which showed photocatalytic activation under visible light activation28. It could be concluded that, in general, the photocatalytic activity of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposite is higher than that of MgAC-Fe3O4 (which has only photo-Fenton activity) but lower than that of MgAC-TiO2 (which also has photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation). The advantages of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 relative to MgAC-TiO2 come from its recycling utility. The difference of photocatalytic activity between the two might come from their respective synthesis processes and material structures. In the case of MgAC-TiO2, nitrogen from the amino-functional groups of MgAC can be doped into the TiO2 structure via a calcination process, thus inducing photocatalytic activity under visible light57. However, in the case of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites, the nitrogen element is removed by the process of the synthesis of MgAC-Fe3O4, as suggested above.

Additionally, the surface areas, pore sizes and pore volumes of the materials were investigated to characterize their surfaces. As can be seen in Table 3, the surface area, pore size and pore volume of the MgAC-Fe3O4 sample were the lowest (surface area: 34.790 m2/g; pore size: 3.639 nm; pore volume: 0.0356 cm3/g). In the literature, the adsorption capacity of Fe3O4 is lower than that of TiO219. In the present study, the MgAC-TiO2 sample had the largest surface area, pore size and pore volume (surface area: 87.822 m2/g; pore size: 7.595 nm; pore volume: 0.1510 cm3/g). Surprisingly, for the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites, when TiO2 existed on the surfaces of the MgAC-Fe3O4 particles, the surface area was not significantly changed (exception: MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2), whereas the pore size and pore volume were increased. For instance, for MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 (the optimal sample), the pore size and pore volume were 9.4163 and 0.0834 cm3/g, 3 times larger than those of MgAC-Fe3O4. In general, even though the surface areas of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites are not significantly changed, their absorption capacities, via the increased pore sizes and volumes, are higher than that of MgAC-Fe3O4.

Table 3.

BET surface areas, pore sizes and pore volumes of samples in this study.

| Sample | BET surface area (m2/g) | Pore size (nm) | Pore volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MgAC-Fe3O4 | 34.790 | 3.639 | 0.0356 |

| MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2 | 35.159 | 9.4163 | 0.0834 |

| MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2 | 70.244 | 6.652 | 0.1280 |

| MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2 | 31.44 | 10.629 | 0.0899 |

| MgAC-TiO2 | 87.822 | 7.595 | 0.1510 |

Discussion

MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 samples were synthesized via sol-gel methods. The core-shell structure with Fe3O4 as the core component, SiO2 as the middle layer and TiO2 as outer layer was suggested. Based on the laboratory scale, the cost of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 materials has been calculated to around 1,479.80 USD/kg, similar to that of MgAC-TiO2 (1,476.24 USD/kg; Table S3), due to its higher production efficiency (1 g MgAC can produce only 1.08 g of MgAC-TiO2, whereas 1 g MgAC-Fe3O4 can produce 4.4 g of MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2). Another advantage of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 is its quick sedimentation, which enables ~80% of materials to be recovered after 24 hours of self-precipitation. Moreover, with their ferromagnetism was remained after the synthesis process, these hybrid nanocomposites show their recycling potential. However, the remnant toxicity of the treated sample against Daphnia magna indicated the presence of residual phenol intermediate products. The comparison of our study with some remarkable researches in the literature was briefly summarized in the Table 4.

Table 4.

The comparison of our study with some remarkable researches in the literature.

| Preparation Method | Obtained material | Remarkable results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| He et al.18 | Homogenous precipitation | Core-shell Fe3O4-TiO2 |

• Obtained Fe3O4-TiO2 is non-toxic • Fe3+ could be doped into TiO2 and activate the photocatalytic activation under visible light activation |

| Sun et al.19 | One-step calcination | Magnetic Fe3O4-TiO2 |

• The degradation of organic dye by Fe3O4-TiO2 (Fe/TiO2 ratio: 1/200) was enhanced compared to single Fe3O4 and TiO2 • The synergistic of Fe3O4 and TiO2 could be attributed to the high photocatalytic activity |

| Zheng et al.12 | Liquid phase deposition | Waxberry-like microsphere Fe3O4-TiO2 |

• Diameter: ~500 nm • Shell thickness: ~10–20 nm • Remove 40% of MB (10 ppm) after 60 mins under Xenon lamp (300 W) • Could be recycled after photocatalytic reaction |

| Stefan et al.13 | Ultrasound assisted sol-gel | Fe3O4-TiO2: Eu nanocomposite |

• Increase of Eu doping decrease the formation of FeTiO3 • Large surface area and mesoporous strcuture • Remove 85% of RhB (1.0 × 10−5 mol/L) dye after 3 h unter visible light irradiation (400 W halogen lamp) |

| Alzahani53 | Sol-gel | Core shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 | • Under UV light, the photocatalytic performance was higher than commercial TiO2 |

| This study | Sol-gel | MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 |

• The synergistic of Fe3O4 and TiO2 could be attributed to the performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 • Core-shell structure with Fe3O4 as core and TiO2 at outer layer is suggested. • However, the photocatalytic under visible light should be activated in the near future |

For industrial-scale application purposes, the toxicity potential of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 as well as its photo-Fenton and photocatalytic mechanisms should be more thoroughly investigated. Additionally, it is necessary to find a way to induce the photocatalytic activity of such hybrid nanocomposites under visible light.

Methods

Materials

(3-aminopropyl)trielthoxysilane (APTES; ≥98%, 221.37 g/mol), iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (III) (FeCl3 · 6H2O; 97%) and titanium butoxide (TB; 97%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2 · 6H2O; 98%) was purchased from Junsei Chemical (Tokyo, Japan). Ethanol (18 L, 95%) was acquired from Samchun Pure Chemicals (Pyungtack, Korea). NaOH (pellet, 97%) was purchased from Daejung Chemical & Metals (Siheung, Korea). Distilled-deionized water (DI; resistance: >18 mΩ) was employed in all of the experiments.

Synthesis of magnesium aminoclay (MgAC)

For preparation of MgAC, 1.68 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O was dissolved in 40 mL of ethanol. Then, 2 mL of 3-aminopropyltrielthoxylane (APTES) was added and stirred for 8 hours to form a white suspension. The resultant suspension was then centrifuged and washed with ethanol (3 × 50 mL) before being dried at 40 °C and ground into powder58.

Synthesis of magnesium aminoclay-iron oxide (MgAC-Fe3O4) nanocomposites

A total of 0.7 g of MgAC was mixed with 3 g of FeCl3 · 6H2O in 40 mL of DI water, to which mixture 10 mL of NaOH 10 M was added. The solution was stirred for 12 hours and then centrifuged and washed with DI water (3 × 50 mL) and dried at 60 °C to form a brown solid. The brown products were ground into powder and calcinated at 500 °C for 3 hours in a furnace (FU-100TG, Samheung Energy, Korea) under 4% H2/Ar (flow rate: 0.15 L/min) to produce MgAC-Fe3O4 nanocomposites29.

Synthesis of magnesium aminoclay-iron oxide/TiO2 (MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2) hybrid nanocomposites

In order to prepare MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites, respectively 0.05 g, 0.1 g and 0.2 g of MgAC-Fe3O4 were mixed with 1 mL of TB in 40 mL EtOH, to each of which mixtures 0.25 µL of DI water was slowly added; the resultant solutions were denoted MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.05 g]/TiO2, MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.1 g]/TiO2, and MgAC-Fe3O4 [0.2 g]/TiO2, respectively. Each solution was then stirred for at least 12 hours, washed with ethanol (3 × 50 mL) and dried to form a grey solid. The resultant products were then ground and consequently calcinated at 350 °C for 3 hours under air in a muffle furnace to produce MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites28.

Photo-fenton performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on batch scale

A total of 0.1 g of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites was loaded into 100 mL of methylene blue (MB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 10 ppm. After obtainment of equilibrium adsorption, 1 mL of H2O2 (35%) was added, and a 365 nm (24 W) UV light source was turned on. One (1) mL of treated water was withdrawn after an interval of 20 min, and the MB concentration was observed under UV-Vis spectroscopy (Cary 50-UV Vis Spectrophotometers, Varian Inc., USA) at a wavelength of 664 nm28.

The degradation rate of the organic compounds was determined by the equation

where C is the concentration of MB at time (t), Co is the initial MB concentration, and k is the pseudo-first-order rate constant (min−1)19.

Photocatalytic performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on batch scale

For evaluation of the photocatalytic performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites, 0.1 g of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites was loaded into a petri dish of 100 mL of phenol at 5 ppm (≥99%; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After obtainment of equilibrium adsorption, a 365 nm wavelength UV light source (~610 µW/cm2) was turned on. Interval samples were withdrawn after each 20 min, and the remaining organic compounds were detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (for phenol; HPLC, Waters Alliance 2695 Separations Module equipped with Waters 2487 Dual λ Absorbance Detector; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) under the mobile phase of water and acetonitrile in a ratio of 40:60 (v/v) with a flow rate of 1 mL/min59. For detection of phenol, UV absorption was performed at 270 nm.

The recycle usage experiments were conducted to check the stability of materials. After photocatalyst materials were separated from degraded solution, they were washed with DI water and ethanol, then dried in the oven at 60 °C for 12 hours. Then the materials is ready for another photocatalytic experiments. This method was repeated for 5 times53.

Preliminary evaluation of photocatalytic and photo-Fenton performances of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites on pilot scale

The photocatalytic performances of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites were tested using the systems introduced in a previous report28. Briefly, MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites were loaded into a reactor (90 cm (width) × 30 cm (depth) × 60 cm (height)) containing 30 L of tap water contaminated with phenol at 3 ppm and stirred with 3 stirrers (GGM speed control motor, Korea) at 145 rpm. After obtainment of equilibrium adsorption, 18 × 365 nm wavelength UV lamps (light intensity: ~610 µW/cm2, 65 cm × 3 cm) were turn on. After an interval of 3 hours, 40 mL of treated water was withdrawn, and the remaining concentration of phenol was determined by HPLC. For evaluation of the photo-Fenton performances of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites, H2O2 was supplied after obtainment of equilibrium adsorption.

For an ecotoxicity test, Daphnia magna was incubated in a 16 h light/8 h darkness cycle at 21 ± 1 °C with M4 medium prepared according to OECD Test Guideline 202 (OECD, 2014)60. The culture medium was replaced daily, and Chlorella was fed once a day. The Daphnia test was carried out according to OECD Test Guideline 202, and young daphanids aged less than 24 hours were collected and exposed to the test materials for 48 hours after Chlorella feeding for 2 hours. In the case of 500 ppm phenol feedstock, 5 daphanids were exposed to 25 mL of 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, and 20 ppm phenol to determine the LC50 (Fig. S1a). Ecotoxicity tests of photo-Fenton- and photocatalytic-treated samples against Daphnia magna also were performed. The toxicity of the photo-Fenton and photocatalytic samples also were investigated, first, via inductive coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES; Optima 7300 DV, Pelkin Elmer, USA) for leakage of iron ions and, second, via total organic carbon (TOC, Vario TOC Cube, Elementar, Germany) for the presence of intermediate products, after the reaction.

Characterization

The crystallography of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites was examined using a Rigaku D/max-2500 (18 kW, Japan) incorporating a θ/θ goniometer equipped with a 40 kV, 30 mA CuKα radiation generator. The morphology of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; SEM-4700, Japan) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-2100F, JEOL Ltd., USA). X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF; MiniPal 2, PANanalytical, Almelo, Netherlands) was employed to identify the elemental compositions of as-prepared samples. The surface areas, pore sizes and pore volumes of the materials were investigated by Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET; Micromeritics ASAP 2010, USA)25. The photoluminescence (PL) spectra were obtained to investigate the electron-hole fate of the semiconductor (DUT-260, Core Bio System, Korea)40. The magnetic properties of the MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites were examined by electron spin resonance spectrometry (ESR; EMXplus/ELEXYS E580, Bruker, USA).

Next, for investigation of the optical properties of the materials, UV photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS; Axis Ultra DLD, Japan) with He I line (21.2 eV) UV source was applied. The work functions of the materials were calculated by the equation

where hv is the incident energy (21.2 eV), Ecutoff is the secondary electron cutoff energy, and Ef is the Fermi energy55.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Korean Ministry of Environment’s GAIA project (2015000550006) and by a grant from the Subway Fine Dust Reduction Technology Development Project of the Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport (19QPPW-B152306-01).

Author Contributions

Vu Khac Hoang Bui and Young-Chul Lee designed the study, prepared materials, conducted the experiment and wrote the manuscript mainly. Vu Khac Hoang Bui and Tuyet Nhung Pham analyzed the structure of materials. Yejin An and Ki-Tae Kim conducted the ecotoxicity experiments. Hyun Uk Lee helped to explain ESR results. Young-Chul Lee and Ki-Tae Kim are corresponding authors of this work. Duckshin Park, Jin Seok Choi, Oh-Hyeok Kwon and Ju-Young Moon contributed comments on the manuscript before submission.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/13/2019

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Contributor Information

Ki-Tae Kim, Email: ktkim@seoultech.ac.kr.

Young-Chul Lee, Email: dreamdbs@gachon.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48398-5.

References

- 1.Daghir R, Drogui P, Robert D. Modified TiO2 for enviromental photocatalytic application: a review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013;52:3581–3599. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weng B, Qi M-Y, Han C, Tang Z-R, Xu Y-J. Photocorrosion inhibition of semiconductor-based photocatalysts: basic principle, current development, and future perspective. ACS Catal. 2019;9:4642–4687. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y-B, et al. Cascade charge transfer mediated by in situ interface modulation toward solar hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7:8938–8951. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Z, et al. Plasmon-induced photoelectrochemical water oxidation enabled by in situ layer-by-layer construction of cascade charge transfer channel in multilayered photoanode. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018;6:24686–24692. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank SN, Bard AJ. Heterogeneous photocatalytic oxidation of cyanide and sulfite in aqueous solutions at semiconductor powders. J. Phys. Chem. 1977;81:1484–1488. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar SG, Rao KSRK. Comparison of modification strategies towards enhanced charge carrier separation and photocatalytic degradation activity of metal oxide semiconductors (TiO2, WO3 and ZnO) Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;391:124–148. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low J, Cheng B, Yu J. Surface modification and enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of TiO2: a review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;392:658–686. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider J, et al. Understanding TiO2 photocatalysis: Mechanisms and materials. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:9919–9986. doi: 10.1021/cr5001892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Q, Kang F, Liu H, Li Q, Xiao X. Highly aligned Cu2O/CuO/TiO2 core/shell nanowire arrays as photocathodes for water photoelectrolysis. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013;1:2418–2425. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emeline AV, Zhang X, Jin M, Murakami T, Fujishima A. Application of a “black body” like reactor for measurements of quantum yields of photochemical reactions in heterogeneous systems. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:7409–7413. doi: 10.1021/jp057115f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zielińska-Jurek A, et al. Magnetic semiconductor photocatalysts for the degradation of recalcitrant chemicals from flow back water. J. Environ. Manage. 2017;195:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng J, et al. Direct liquid phase deposition fabrication of waxberry-like magnetic Fe3O4@TiO2 core-shell microspheres. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016;181:391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefan M, et al. Magnetic recoverable Fe3O4-TiO2: Eu composite nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;390:248–259. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng W, Tang K, Qi Y, Sheng J, Liu Z. One-step synthesis of superparamagnetic monodisperse porous Fe3O4 hollow and core-shell spheres. J. Mater. Chem. 2010;20:1799–1805. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z, Bai H, Sun DD. Facile fabrication of porous chitosan/TiO2/Fe3O4 microspheres with multifunction for water purifications. New J. Chem. 2011;35:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia X, et al. Facile synthesis and enhanced magnetic, photocatalytic properties of one-dimensional Ag@Fe3O4-TiO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;392:268–276. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma J, Guo S, Guo X, Ge H. A mild synthetic route to Fe3O4@TiO2-Au composites: preparation, characterization and photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015;353:1117–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Q, Zhang Z, Xiong J, Xiong Y, Xiao H. A novel biomaterial — Fe3O4: TiO2 core-shell nano particle with magnetic performance and high visible light photocatalytic activity. Opt. Mater. 2008;31:380–384. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Q, Hon Y, Liu Q, Dong L. Synergistic operation of photocatalytic degradation and Fenton process by magnetic Fe3O4 loaded TiO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;430:399–406. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S-H, Zhang N, Xie X, Luque R, Xu Y-J. Stress-transfer-induced in situ formation of ultrathin nickel phosphide nanosheets for efficient hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. 2018;130:13266–13269. doi: 10.1002/anie.201806221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu K-Q, Xin X, Zhang N, Tang Z-R, Xu Y-J. Photoredox catalysis over graphene aerogel-supported composites. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018;6:4590–4604. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkett SL, Press A, Mann S. Synthesis, characterication and reactivity of layer inorganic-organic nanocomposites based on 2:1 trioctanhedral phyllosilicates. Chem. Mater. 1997;9:1071–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann S, et al. Sol-gel synthesis of organized matter. Chem. Mater. 1997;9:2300–2310. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whilton NT, Burkett SL, Mann S. Hybrid lamellar nanocomposites based on organically functionalized magnesium phyllosilicate clays with interlayer reactivity. J. Mater. Chem. 1998;8:1927–1932. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bui VKH, Park D, Lee Y-C. Aminoclays for biological and environmental applications: An updated review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;336:757–775. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arvaniti OS, et al. Reductive degradation of perfluorinated compounds in water using Mg-aminoclay coated nanoscale zero valent iron. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;262:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Jing G, Zhou X, Lv B. Removal of chromium (VI) from wastewater by Mg-aminoclay coated nanoscale zero-valent iron. J. Water Process Eng. 2017;18:134–143. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bui VKH, et al. One-pot synthesis of magnesium aminoclay-titanium dioxide nanocomposites for improved photocatalytic performance. J. Nanosci. Nanotech. 2018;18:6070–6074. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2018.15606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bui VKH, Pham TN, Lee Y-C. One-pot synthesis of magnesium aminoclay-iron oxide nanocomposites for improved photo-Fenton catalytic performance. J. Nanosci. Nanotech. 2019;19:1069–1073. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2019.15942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Y-C, et al. Aminoclay-conjugated TiO2 synthesis for simultaneous harvesting and wet-disruption of oleaginous Chlorella sp. Chem. Eng. J. 2014;245:143–149. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Bohwa, Bui Vu, Farooq Wasif, Jeon Sang, Oh You-Kwan, Lee Young-Chul. Magnesium Aminoclay-Fe3O4 (MgAC-Fe3O4) Hybrid Composites for Harvesting of Mixed Microalgae. Energies. 2018;11(6):1359. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Zhou X. Degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol by nanoscale calcium peroxide: Implication for groundwater remediation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016;166:222–229. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu L, et al. Degradation of phenol using Fe3O4-GO nanocomposite as a heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016;171:80–87. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao L, et al. Photocatalytic oxidation of toluene on nanoscale TiO2 catalysts: studies of deactivation and regeneration. J. Catal. 2000;196:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahvi AH, Maleki A, Alimohamadi M, Ghasri A. Photo-oxidation of phenol in aqueous solution: toxicity of intermediates. Korean J. Chem Eng. 2007;24:79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 36.An T, et al. Photocatalytic degradation and mineralization mechanism and toxicity assessment of antivirus drug acyclovir: Experimental and theoretical studies. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2015;164:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talukdar S, Dutta RK. A mechanistic approach for superoxide radicals and singlet oxygen mediated enhanced photocatalytic dye degradation by selenium doped ZnS nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2016;6:928–936. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du D, Shi W, Wang L, Zhang J. Yolk-shell structured Fe3O4@void@TiO2 as a photo-Fenton-like catalyst for the extremely efficient elimination of tetracycline. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2017;200:484–492. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weng B, Lu K-Q, Tang Z, Chen HM, Xu Y-J. Stabilizing ultrasmall Au clusters for enhanced photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1543. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04020-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen F, et al. Fabrication of Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2 nanoparticles supported by graphene oxide sheets for the repeated adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B under UV irradiation. Dalton T. 2014;36:13537–13544. doi: 10.1039/c4dt01702a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, et al. Preparation of magnetic Fe3O4/TiO2/Ag composite microspheres with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Solid State Sci. 2016;52:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization. In Guidelines for drinking-water quality (Geneva, 1996).

- 43.Wang SG, et al. Evidence for FeO formation at the Fe/MgO interface in epitaxial TMR structure by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007;310:1935–1936. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giorgi L, et al. Electrochemical synthesis of self-organized TiO2 crytalline nanotubes without annealing. Nanotechnology. 2018;29:095604. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aaa448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han F, Ma L, Sun Q, Lei C, Lu A. Rationally designed carbon-coated Fe3O4 coaxial nanotubes with hierarchical porosity as high-rate anodes for lithium ion batteries. Nano Res. 2014;7:1706–1717. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, G., Li, R. & Zhou, W. A wire-shaped supercapacitor in micrometer size based on Fe3O4 nanosheet arrays on Fe wire. Nano-Micro Lett. 9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Chimupala Y, et al. Synthesis and characterization of mixed phase anatase TiO2 and sodium doped TiO2(B) thin fims by low pressure chemical vapour deposition (LPCVD) RCS Adv. 2014;4:48507–48517. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka K, Kamiya K, Matsuoka M, Yoko T. ESR study of a sol-gel-derived amorphous Fe2O3-SiO2 system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 1987;94:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jitianu A, Crisan M, Meghea A, Rau I, Zaharescu M. Influence of the silica based matrix on the formation of iron oxide nanoparticles in the Fe2O3-SiO2 system, obtained by sol-gel method. J. Mater. Chem. 2002;12:1401–1407. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cannas C, Gatteschi D, Musinu A, Piccaluga G, Sangregorio C. Structural and Magnetic Properties of Fe2O3 nanoparticles dispersed over a silica matrix. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:7721–7726. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zubir NA, Yacou C, Motuzas J, Zhang X, Diniz da Costa JC. Structural and functional investigation of graphene oxide–Fe3O4 nanocomposites for the heterogeneous Fenton-like reaction. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4594. doi: 10.1038/srep04594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Matteis L, et al. Influence of a silica interlayer on the structural and magnetic properties of sol–gel TiO2-coated magnetic nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2014;30:5238–5247. doi: 10.1021/la500423e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alzahrani E. Photodegradation of binary azo dyes using core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanospheres. Am. J. Analyt. Chem. 2017;08:95–115. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang R, Wang X, Xi X, Hu R, Jiang G. Preparation and photocatalytic activity of magnetic Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2. composites. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2012;2012:8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee SC, et al. Hierarchically three-dimensional (3D) nanotubular sea urchin-shaped iron oxide and its application in heavy metal removal and solar-induced photocatalytic degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018;354:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu F, et al. Fabrication of vertically aligned single-crystalline boron nanowire arrays and investigation of their field-emission behavior. Adv. Mater. 2008;20:2609–2615. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu W, Xiao X, Zhang S, Ren F, Jiang C. Facile method to synthesize magnetic iron oxides/TiO2 hybrid nanoparticles and their photodegradation application of methylene blue. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011;6:533. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patil AJ, Li M, Dujardin E, Mann S. Novel bioinorganic nanostructures based on mesolamellar intercalation or single-molecule wrapping of DNA using organoclay building blocks. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2660–2665. doi: 10.1021/nl071052q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Z, et al. Highly ordered TiO2 nanotube arrays with controllable length for photoelectrocatalytic degradation of phenol. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2004).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.