Abstract

Aggregation of the disordered protein α‐synuclein into amyloid fibrils is a central feature of synucleinopathies, neurodegenerative disorders that include Parkinson's disease. Small, pre‐fibrillar oligomers of misfolded α‐synuclein are thought to be the key toxic entities, and α‐synuclein misfolding can propagate in a prion‐like way. We explored whether a compound with anti‐prion activity that can bind to unfolded parts of the protein PrP, the cyclic tetrapyrrole Fe‐TMPyP, was also active against α‐synuclein aggregation. Observing the initial stages of aggregation via fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy, we found that Fe‐TMPyP inhibited small oligomer formation in a dose‐dependent manner. Fe‐TMPyP also inhibited the formation of mature amyloid fibrils in vitro, as detected by thioflavin T fluorescence. Isothermal titration calorimetry indicated Fe‐TMPyP bound to monomeric α‐synuclein with a stoichiometry of 2, and two‐dimensional heteronuclear single quantum coherence NMR spectra revealed significant interactions between Fe‐TMPyP and the C‐terminus of the protein. These results suggest commonalities among aggregation mechanisms for α‐synuclein and the prion protein may exist that can be exploited as therapeutic targets.

Keywords: protein aggregation, cyclic tetrapyrrole, fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy, isothermal titration calorimetry

Abbreviations

- Cy5

cyanine 5

- FCCS

fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy

- Fe‐TMPyP

iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine)

- IPTG

isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- LB

Luria‐Bertani broth

- OG

Oregon Green 488

- ThT

thioflavin T

- TPM

trans‐cyclooctene‐(polyethylene glycol)3‐maleimide

1. INTRODUCTION

α‐Synuclein is an intrinsically disordered protein1, 2 abundant in presynaptic neurons of the central nervous system.3, 4 Native monomeric α‐synuclein can misfold and aggregate into a variety of oligomeric forms5, 6, 7 that ultimately lead to insoluble cross‐β‐structured amyloid fibrils8, 9 deposited as Lewy bodies and/or Lewy neurites in neurons.10, 11 Furthermore, the misfolding can propagate in a prion‐like fashion via intra‐ and trans‐neuronal spread of misfolded protein.12 This progressive cascade of events is proposed to play a key role in the pathogenesis of α‐synucleinopathies, a group of neurodegenerative disorders that includes Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy.13, 14, 15 α‐Synuclein has also been linked to the cross‐seeded fibrillization of aβ peptide and tau, proteins involved in plaque formation, and neurofibrillary tangle accumulation in Alzheimer's disease.16, 17, 18

Abundant evidence has implicated α‐synuclein oligomers as toxic agents in synucleinopathies,19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 motivating efforts to discover aggregation inhibitors as therapeutics to delay or halt the progressive decline in motor and cognitive abilities experienced by patients.25, 26, 27, 28 A wide range of aggregation inhibitors has been explored, including polyphenols,29, 30, 31 tetrapyrroles,32 phenothiazines,33 stilbenes,34 antibody reagents,35, 36, 37 and various peptide ligands.38, 39, 40, 41 Particularly interesting among these inhibitors are cyclic tetrapyrroles and related molecules (e.g., porphyrins, phthalocyanines, and corrins), which have been shown to modify the aggregation of multiple proteins exhibiting prion‐like propagated misfolding, including Aβ,42, 43 tau,44, 45 and prion protein (PrP).46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 In some cases, these compounds are proposed to stabilize off‐pathway oligomers,52, 53 whereas in others, they are proposed to stabilize monomers54 or interfere with interactions stabilizing larger aggregates,55 but in most cases, their mechanism of action is incompletely understood.

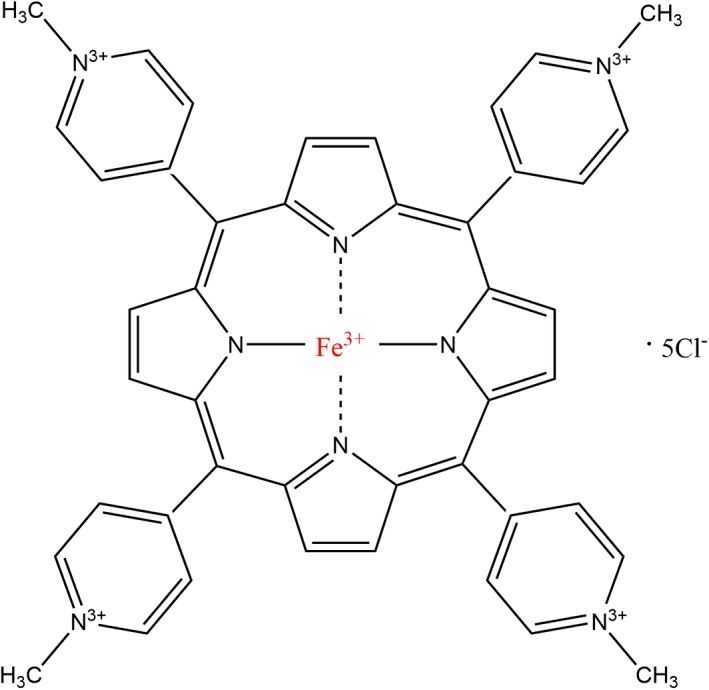

Here we have examined the effects on α‐synuclein of a tetrapyrrole that was initially discovered in a screen for inhibitors of prion disease, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine) (Figure 1), denoted hereafter as Fe‐TMPyP. Fe‐TMPyP, which was first proposed to act by stabilizing the natively structured C‐terminal domain of PrP,46 via specific binding with a stoichiometry of 1, is effective at inhibiting a broad range of prion strains,50 unlike other anti‐prion compounds.55, 56 However, it was later found to have high affinity also for the C‐terminal domain when unfolded, with its binding preventing the formation of stable misfolded aggregates.51 These results raise the interesting question of whether it has similar inhibitory properties against α‐synuclein.

Figure 1.

Fe‐TMPyP structure. Iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine) is a planar molecule with a ferric ion centrally coordinated within a porphyrin ring that is circumscribed peripherally by four positively charged methyl‐pyridinium moieties. Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine)

We tested the effects of Fe‐TMPyP on α‐synuclein at different stages in the aggregation cascade using a suite of biophysical and biochemical assays. The last stages of aggregation, namely formation and growth of mature amyloid fibrils, were assayed with thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence, whereas the earliest stages of aggregation were assayed using fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy (FCCS),57 which provides a more direct probe of the nucleation and growth of small oligomers.58 Fe‐TMPyP was found to inhibit both small oligomers and mature fibrils. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was used to quantify Fe‐TMPyP interactions with monomeric α‐synuclein, showing that it binds at a defined stoichiometry. Finally, two‐dimensional heteronuclear single quantum coherence NMR spectroscopy was used to determine the regions where α‐synuclein and Fe‐TMPyP interacted most prominently.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Concentration‐dependent effect of Fe‐TMPyP on amyloid fibril formation in vitro

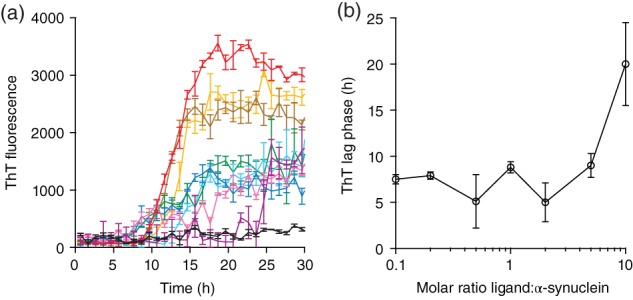

We first examined the effect of Fe‐TMPyP on the formation of mature amyloid fibrils, using the fluorescence from ThT, a dye whose absorption and emission spectra change upon binding to amyloid.59 ThT fluorescence was measured for samples incubated in a 96‐well microplate under standard aggregation conditions (see Materials and Methods), with varying amounts of Fe‐TMPyP present (at ligand:protein molar ratios of 0:1, 1:10, 1:5, 1:2, 1:1, 2:1, 5:1, and 10:1), to monitor the growth of fibrils over time (Figure 2a). Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a polyphenol previously demonstrated to bind α‐synuclein and inhibit fibrillization,31, 60, 61 was used as a positive control at a ligand:protein molar ratio of 10:1 (Figure 2a, black). In the absence of ligand (Figure 2a, red), α‐synuclein formed fibrils after a lag period of ∼7 hr, during which no change in ThT fluorescence was detected. Thereafter, the fluorescence rose rapidly, reflecting the growth of amyloid fibrils,44 until saturation was reached at ∼18 hr. Following saturation, the fluorescence dropped gradually owing to dye photobleaching. As Fe‐TMPyP was added and its concentration increased from 1/10 the protein concentration to a twofold excess (Figure 2a, orange, brown, green, cyan, blue), there was no change in the lag phase (Figure 2b) and saturation was reached in a similar timeframe, but the amount of amyloid present at saturation was systematically reduced by roughly threefold. Between a 5‐ and 10‐fold molar excess of Fe‐TMPyP (Figure 2a, pink and purple, respectively), there was no further reduction in the extent of amyloid formation, but the lag phase began to increase, with little detectable change at fivefold excess but a roughly threefold increase to ∼20 hr at 10‐fold excess (Figure 2b), and saturation was delayed to ∼23 and 25 hr, respectively. For comparison, the EGCG control (Figure 2a, black) revealed no detectable lag phase or increase in fluorescence arising from fibril formation.

Figure 2.

Fe‐TMPyP decreases α‐synuclein fibrillization extent and increases lag phase as assayed by ThT fluorescence. (a) ThT fluorescence shows concentration‐dependent inhibition of amyloid fibril formation for different molar ratios of Fe‐TMPyP:α‐synuclein: 0:1 (red), 1:10 (orange), 1:5 (brown), 1:2 (green), 1:1 (cyan), 2:1 (blue), 5:1 (pink), and 10:1 (purple). Curve in black shows results using a 10:1 molar ratio of EGCG. (b) The lag phase of fibril formation starts to rise above a 5:1 molar ratio. Error bars show SEM. EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate; Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine)

These results indicated that Fe‐TMPyP had a more complex effect on fibril formation by α‐synuclein than compounds like EGCG that suppress it entirely. As the concentration of Fe‐TMPyP increased, first it reduced the amount of fibril formed without changing the lag phase, suggesting that the ligand binding reduced the amount of protein competent to form fibrils but did not affect the rate‐limiting step for fibril formation. At higher concentrations, however, where the amount of fibril formed stopped falling but the lag phase started increasing, Fe‐TMPyP began to alter the rate‐limiting step for fibril formation. Two distinct effects of Fe‐TMPyP binding were thus observed.

2.2. Fe‐TMPyP inhibits oligomer formation as observed by FCCS

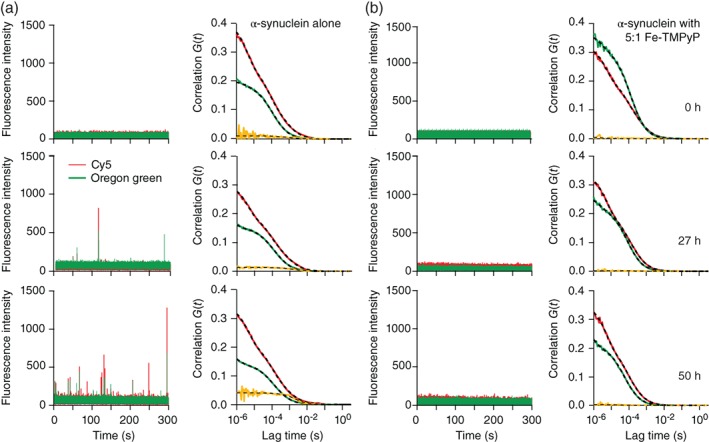

To probe the early stages of aggregation in more detail than is possible with ThT fluorescence, we used two‐color FCCS, following previous work characterizing aggregate nucleation in α‐synuclein.58 Monomeric α‐synuclein aliquots labeled either with Oregon green 488 (OG) or Cy5 were mixed in high equimolar concentrations to induce association (see Section 4). At various time points, samples were taken from the reaction, diluted to nM concentrations, and measured in a two‐color fluorescence confocal microscope. Dye‐labeled molecules diffusing through the confocal excitation volume produced fluctuations in the fluorescence, which were then analyzed to study the auto‐correlations in the green and red fluorescence as well as the cross‐correlation between the green and red signals. Because the auto‐correlation signals contain contributions from a large background of monomers, but the cross‐correlation signal reflects only the presence of aggregates, the presence of dual‐colored assemblies was used as a sensitive probe of the early stages of aggregation.58

Measurements of α‐synuclein alone, without ligand, showed negligible cross‐correlations before incubation to induce aggregation (Figure 3a, top right, orange), but the number and amplitude of dual‐color fluctuations grew as the aggregation time was increased from 0 to 50 hr (Figure 3a, left), leading to growth of the cross‐correlation signal (Figure 3a, right, orange). When Fe‐TMPyP was added to the reaction mixture before aggregation, however, the dual‐color fluctuations were largely suppressed (Figure 3b, left), and negligible cross‐correlation signals were seen even after 50 hr of incubation to induce aggregation (Figure 3b, right, orange).

Figure 3.

Fe‐TMPyP suppresses α‐synuclein oligomers monitored by fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy. (a) Large fluorescence fluctuations from Cy5‐ (red) and OG‐labeled (green) α‐synuclein (left panels) are seen more often as the incubation time increases from 0 to 50 h. The corresponding auto‐correlation (Cy5, red; OG, green) and cross‐correlation (orange) curves (right panels) fit to Equations 1, 2, 3 (dashed lines) show increasing cross‐correlation amplitude and diffusion time, indicating the growth of oligomers. (b) Measurements repeated with a fivefold molar excess of Fe‐TMPyP show no large fluorescence fluctuations (left panels) and suppression of the cross‐correlation signal (right panels). Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine)

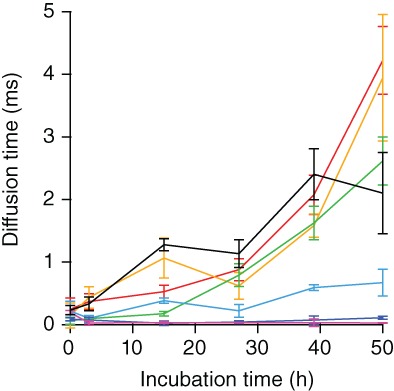

These FCCS measurements were repeated at different concentrations of Fe‐TMPyP, ranging from ligand:protein molar ratios of 1:4 to 5:1, as well as with the control ligand EGCG. The auto‐ and cross‐correlation functions were then fit Equations. 1, 2, 3 (see Section 4) as described previously58 to determine the diffusion time for the dual‐colored oligomeric assemblies as they moved through the confocal volume. Increases in the diffusion time indicated an increase in the size of the aggregates formed. For α‐synuclein alone, a monotonically increasing diffusion time was observed (Figure 4, red), revealing a progressive growth in oligomer size as aggregation progressed. With an excess of protein over ligand (Figure 4, orange and green), the diffusion time increased with aggregation time, but less steeply than without ligand present. As the concentration of ligand was increased to be in excess of the protein (Figure 4, cyan, blue), the rise in diffusion time (and hence aggregate size) was suppressed further, until at a fivefold excess oligomers were difficult to detect (Figure 4, purple). For comparison, a fivefold molar excess of the control ligand EGCG (Figure 4, black) resulted in increased diffusion time compared to α‐synuclein alone for the first ∼40 hr of aggregation, consistent with the proposal that EGCG stabilizes off‐pathway oligomers in α‐synuclein.31

Figure 4.

Fe‐TMPyP decreases oligomer size in FCCS assay. The diffusion time in FCCS assays decreases with increasing Fe‐TMPyP concentration, reflecting smaller oligomers, until oligomers are abolished above 5:1 ligand:protein molar ratios. Red, no ligand; orange, 1:4 molar ratio of Fe‐TMPyP to α‐synuclein; green, 1:2 molar ratio; cyan, 1:1 molar ratio; blue, 2:1 molar ratio; purple, 5:1 molar ratio; and black, 5:1 molar ratio of EGCG to α‐synuclein. Error bars show SEM. EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate; FCCS, fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy; Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine)

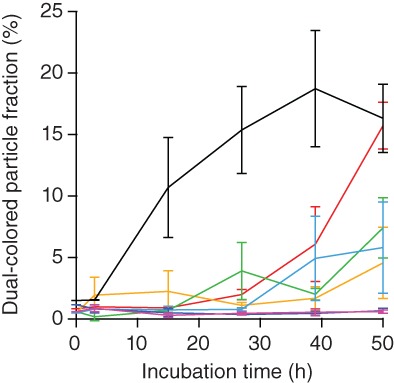

The fraction of particles that contained both dye colors, reflecting the extent of oligomer formation, was also quantified from the FCCS measurements, using the relationship between the amplitude of the correlation function and the number fluorescent particles present in the confocal volume.45, 58 The concentration of green‐, red‐, and dual‐colored particles was calculated from the correlation amplitudes and confocal volume yielding the fraction of all α‐synuclein particles represented by dual‐colored aggregates (Figure 5, see Section 4). This fraction rose to ∼15% after 50 hr for α‐synuclein alone (Figure 5, red), but was reduced by increasing amounts of Fe‐TMPyP, becoming close to zero for a twofold to fivefold excess of ligand (Figure 5, blue and purple). In contrast, EGCG induced significant oligomer formation within a few hours of incubation, several times more than in α‐synuclein alone (Figure 5, black).

Figure 5.

Fe‐TMPyP reduces the extent of oligomer formation. The fraction of particles that contain both dye labels in FCCS measurements is reduced with increasing molar ratios of ligand to protein (red, no ligand; orange, 1:4 Fe‐TMPyP:α‐synuclein; green,1:2; cyan, 1:1; blue, 2:1; purple, 5:1; and black, 5:1 molar ratio of EGCG:α‐synuclein. Error bars represent SEM. EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate; FCCS, fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy; Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine)

We note that the time‐scales for aggregation in the FCCS measurements cannot be directly compared to the time‐scales in the ThT measurements, because different protein concentrations and experimental conditions were used, strongly affecting the time for aggregation. Previous work measuring the growth of fibrils via ThT fluorescence under the same conditions as used here for FCCS, however, provides a point of comparison (Figure S2). The lag phase in the latter measurement, ∼60 hr, indicated that all of the aggregates characterized by the FCCS measurements reflect oligomers formed during the lag phase before mature fibril formation.

2.3. Fe‐TMPyP binds stoichiometrically to α‐synuclein monomers, interacting primarily with the C terminus

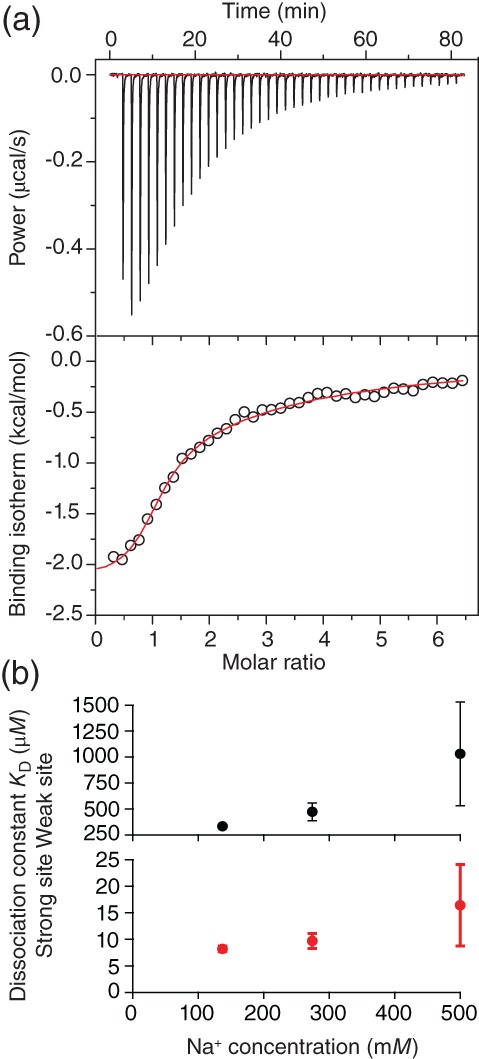

The results of the FCCS assays suggest that the ligand likely binds to the monomeric protein, since it inhibits monomers from interacting and nucleating oligomers. We therefore used ITC to quantify the interaction between Fe‐TMPyP and monomeric α‐synuclein by measuring the rate of heat produced from the binding as the ligand was titrated in (Figure 6a, upper panel). The resulting binding isotherm reflecting the integrated heat of reaction (Figure 6a, lower panel) was well fit by a model consisting of two binding sites (stoichiometry of 2.0 ± 0.1). The fits (Figure 6a, red) indicated one strong binding interaction, with dissociation constant 8.2 ± 0.5 μM, binding enthalpy −2.12 ± 0.03 kcal/mol, and binding entropy 16.0 ± 0.2 cal/mol °C, and one weak site, with dissociation constant 330 ± 20 μM, binding enthalpy −4.38 ± 0.03 kcal/mol, and binding entropy 1 ± 0.2 cal/mol °C. Thus, Fe‐TMPyP does indeed bind to monomeric protein, with an affinity at the strong‐binding site that is very similar to the affinity found previously for binding of Fe‐TMPyP to the structured domain of PrPC under similar solution conditions.51 Repeating the ITC measurements at different Na+ concentrations to modulate any electrostatic interactions, we found that K D increased modestly for the strong binding site (Figure 6b, red), but substantially for the weak binding site, becoming difficult to measure at 500 mM Na+ (Figure 6b, black).

Figure 6.

ITC reveals stoichiometric Fe‐TMPyP binding to α‐synuclein monomers. (a) Two binding sites were found by fitting the baseline‐subtracted binding isotherm (red), one with high affinity (K D = 8.2 μM) and one with low affinity (K D = 330 μM). (b) Binding at the high‐affinity site was weakened modestly by increasing [Na+] (red), whereas that at the low‐affinity site was weakened significantly (black). Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine); ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry

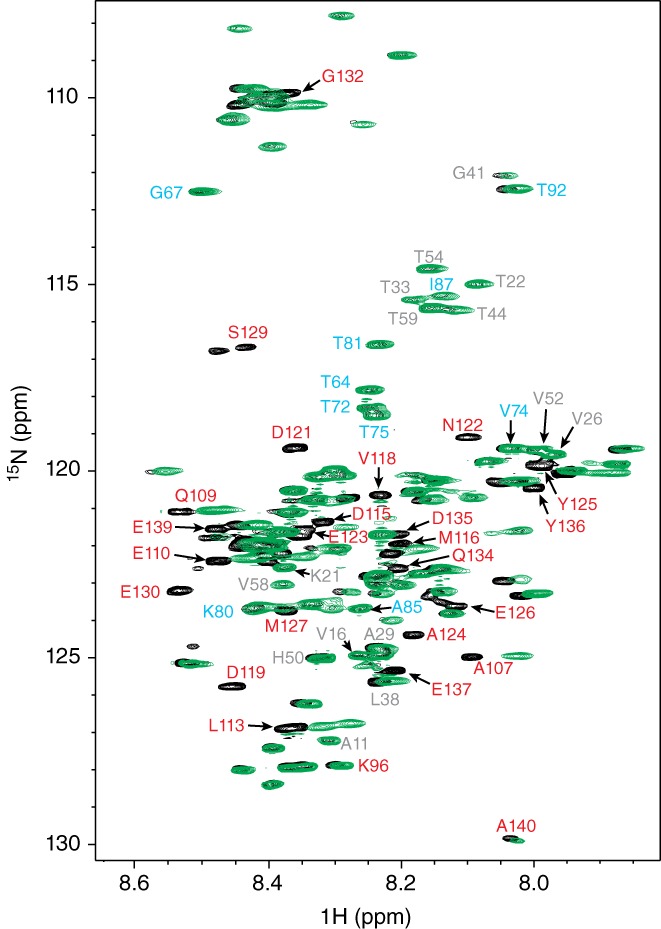

To explore what parts of α‐synuclein interact with Fe‐TMPyP, we monitored backbone perturbations in the protein using 2D‐[1H,15N]‐HSQC NMR spectroscopy.62, 63 Spectra measured at 800 MHz from protein labeled uniformly with 15N were compared for α‐synuclein alone (Figure 7, black), and for α‐synuclein in the presence of a fivefold molar excess of Fe‐TMPyP (Figure 7, green). As reported previously for α‐synuclein,64, 65 relatively poor chemical‐shift dispersion was observed in the 1H dimension, but the dispersion in the 15N dimension was more pronounced. Roughly 130 backbone peaks were resolved for α‐synuclein in the absence of ligand, close to the expected total of 134 nonoverlapping backbone peaks (excluding the initial methionine and non‐observable prolines). In the presence of Fe‐TMPyP, 109 backbone peaks were resolved. Based on the similarity of the observed backbone amide chemical shifts with previous Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB)66 depositions (access codes 19257,67 19337,68 19346,68 25227,69 27074,70 and 2734871), we assigned many of the observed [15N, 1H] resonances, as shown in Figure 7. This analysis identified residues whose backbone chemical environment was modified in the presence of Fe‐TMPyP. We found that backbone resonances shifted or disappeared in the presence of ligand almost exclusively among residues in the highly acidic C‐terminal region (Figure 7, red).

Figure 7.

2D‐[1H,15N]‐HSQC NMR spectroscopy of Fe‐TMPyP binding to α‐synuclein. Changes in the spectral peaks for α‐synuclein alone (black) and with fivefold molar excess of Fe‐TMPyP (green) indicate which parts of the protein are most affected by binding. Most of the peaks strongly affected (shifted or absent) by Fe‐TMPyP binding were located in the acidic C‐terminal domain (red), whereas residues in the hydrophobic NAC domain (cyan) or the N‐terminal region (gray) were little changed. Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine); HSQC, two‐dimensional heteronuclear single quantum coherence

3. DISCUSSION

The results presented above begin to assemble a picture of how Fe‐TMPyP interacts with α‐synuclein. First, it binds to monomeric α‐synuclein with a stoichiometry of 2, where one binding site has low‐μM affinity and the other closer to mM affinity, interacting primarily with the C‐terminal domain of the protein. These interactions had a relatively modest effect on the formation of small oligomers at low concentrations, as detected by FCCS, but at equimolar concentrations or higher they significantly suppressed both the fraction of proteins forming oligomers and the size of the oligomers formed. Similar trends were seen when looking at fibril formation, with modest effects at low concentrations, but suppression of fibril formation at higher concentrations. Curiously, however, where the suppression of oligomers was near‐total at high Fe‐TMPyP concentrations, the suppression of fibril formation seemed to saturate at ∼35% of the amount of fibril formed in the absence of Fe‐TMPyP, as quantified by ThT fluorescence intensity. Furthermore, even as the size and number of early oligomers were being suppressed by Fe‐TMPyP at moderate concentrations, the lag phase remained unchanged for all but the highest Fe‐TMPyP concentration probed.

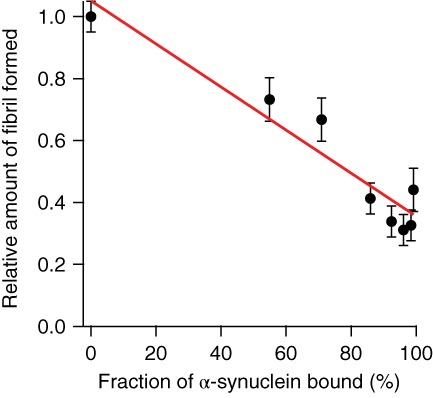

These observations suggest that the rate‐limiting step for fibril nucleation likely does not involve the larger oligomers that were the first species to be suppressed at moderate Fe‐TMPyP concentrations, but rather some population of the much smaller species that only began to be suppressed at the highest concentrations. The suppression of the amount of fibril formed before there is any change in the lag phase, moreover, suggests that Fe‐TMPyP reduces the amount of α‐synuclein available to fibrillize, possibly by making the ligand‐bound monomers incapable of adding to growing fibrils. To test this hypothesis, we calculated the fraction of α‐synuclein monomer expected to be ligand‐bound for each measurement at different Fe‐TMPyP concentrations, given the binding affinity measured by ITC, and compared it to the amount of fibril formed as measured by the intensity of ThT fluorescence after the end of the growth phase (Figure 8). We indeed found a relationship that was roughly linear (linear fit: r 2 = .91), as would be expected from the picture proposed. The line of best fit (Figure 8, red) showed that the amount of fibril formed at high ligand concentration, with ∼100% of α‐synuclein ligand‐bound, was ∼35% of the amount of fibril formed without ligand present, suggesting that ∼65% of the Fe‐TMPyP‐bound protein was unable to form fibrils.

Figure 8.

Amount of fibril formed is reduced by Fe‐TMPyP binding. The amount of fibril formed, reflected in the ThT fluorescence amplitude at saturation, is reduced roughly linearly (red line: linear fit, r 2 = .91) by Fe‐TMPyP binding, suggesting ~65% of Fe‐TMPyP‐bound α‐synuclein cannot form fibrils. Fe‐TMPyP, iron(III) meso‐tetra (N‐methyl‐4‐pyridyl‐prophine); ThT, thioflavin T

From the NMR spectra, the interactions driving these effects on α‐synuclein aggregation involve predominantly residues in the C‐terminal domain of the protein. This domain has two notable features that are very suggestive for the binding mechanism of Fe‐TMPyP. First, the C‐terminal domain is acidic, containing many negatively charged residues, which would be expected to enhance binding of positively charged ligands like Fe‐TMPyP. Indeed, most of the negative residues in the C‐terminal domain (including E110, D115, D119, D121, E123, E126, E130, D135, E137, and E139) show shifted or absent NMR peaks upon ligand binding, indicating significant perturbation by the ligand. These effects are reminiscent of the NMR results found for the binding of positively charged polyamines to α‐synuclein,72 which similarly induced many backbone shifts in the C terminus. Positive polyamines have been found to promote aggregation,72, 73 however, casting doubt on electrostatic interactions between Fe‐TMPyP and α‐synuclein being the primary mechanism inhibiting aggregation. Indeed, the salt‐dependence of the binding, where it is the weak binding that is highly salt‐dependent, suggests that electrostatic interactions with acidic C‐terminal residues primarily stabilize the secondary binding site, not the strong binding site that is presumably most responsible for aggregation inhibition.

The second notable feature of the C‐terminal domain is that it contains three of the four tyrosine residues of the protein (Y125, Y133, and Y136), which could interact specifically and strongly with Fe‐TMPyP via π–π interactions between the aromatic rings of the tetrapyrrole and tyrosine residues to modulate aggregation.74 Indeed, the peaks for Y125 and Y136 were absent with Fe‐TMPyP bound, although Y133 could not be assigned with confidence. Furthermore, previous work found that α‐synuclein aggregation could be attenuated by a small molecule (fasudil) that interacted specifically with Y133 and Y136,75 suggesting that interactions with the C‐terminal tyrosines might provide a route to suppress aggregation. Interestingly, a different porphyrin, phthalocyanine tetrasulfonate (PcTS), was found to bind to Y39 in the N‐terminus, instead of the C‐terminal tyrosines,76 presumably because PcTS is negatively charged and hence experiences repulsion from the many negatively charged residues in the C terminus. Given that the C‐terminal tyrosines are close to many of the acidic patches, the combination of specific π–π interactions with the aromatic side chains and electrostatic attractions with the negative residues may account for the potency of Fe‐TMPyP as an oligomerization inhibitor. The weak salt‐dependence of the primary binding site of Fe‐TMPyP on α‐synuclein supports the notion that both electrostatic and π–π interactions are involved, but that the latter are most important for stabilizing the binding.

An intriguing aspect of this work on interactions between Fe‐TMPyP and α‐synuclein is its implications for understanding the role of Fe‐TMPyP as an anti‐prion agent. Although Fe‐TMPyP was originally proposed to act by stabilizing the structured domain of PrP,48 it was later shown also to interact with unfolded PrP and help PrP to fold into its native structure by preventing the formation of stable misfolded states.51 Although PrP does not contain as many concentrated regions of charged residues as α‐synuclein, it has many more aromatic residues, including 11 tyrosines in the structured domain alone as well as multiple tyrosines and tryptophans in the unstructured N terminus. We speculate that Fe‐TMPyP may interact with specific tyrosines in unfolded PrP, analogous to the interactions seen in α‐synuclein, and that these interactions help provide protection against misfolded oligomer formation in both cases. Such a mechanism of action would provide additional support for the hypothesis that the unfolded state plays an important role in prion formation and propagation,77, 78 pointing to potential commonalities in the aggregation mechanisms for disordered proteins like α‐synuclein and more ordered proteins like PrP, and motivating future study of other anti‐prion compounds that may be effective at inhibiting α‐synuclein aggregation.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Materials

Unless noted specifically, all chemicals and reagents were of highest quality from Sigma‐Aldrich Canada (Oakville, ON) or from ThermoFisher Canada (Edmonton, AB). Columns for anion exchange chromatography (Q‐sepharose FF) and size‐exclusion chromatography (SEC) (sephacryl S200 HiPrep) were from GE Life Sciences. Both the Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) strain for protein expression and the pET21b expression vector were sourced from EMD Millipore.

4.2. Recombinant α‐synuclein production

Recombinant α‐synuclein protein, both wild type and a version with a Cys residues appended to the C terminus for fluorophore labeling, was prepared as described previously,79 with minor modifications.58, 80 Briefly, the open reading frames were inserted into pET21b expression vectors, and then used to transform E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells to ampicillin resistance. Protein expression was induced at the mid‐logarithmic growth stage of the culture using 1 mM isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and cultures were harvested 6 hr later. Harvested bacterial cells were resuspended in an osmotic‐shock buffer (30 mM Tris pH 7.2, 40% [w/v] sucrose, 2 mM EDTA); at this point, and in all subsequent buffers, 2 mM Tris(2‐carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) was added when preparing the cysteine mutant to ensure the sulfhydryl group was reduced. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation (21,036g, 40 min) and the resulting pellet resuspended in 90 mL ice‐cold MilliQ H2O containing 37.5 μL of saturated MgCl2. The sample was kept on ice for 10 min, then centrifuged again (21,036 g, 40 min) to pellet the cells. The resulting supernatant containing proteins released from the E. coli periplasm was subjected to ammonium sulfate precipitation: saturated ammonium sulfate was added and brought to a final concentration of 40% w/v to precipitate the protein, incubating overnight at 4°C with gentle stirring. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation (75,600g, 60 min), decanting the supernatant, and subjected to further purification by anion‐exchange chromatography.

4.3. Expression of 15N‐labeled α‐synuclein

A single colony of pET21‐transformed Rosetta 2 (DE3) expression strain was used to inoculate an overnight culture (LB + 100 μg/mL ampicillin), whose cells were then used as inoculum for 1 L Modified Terrific Broth media with 100 μg/mL ampicillin preheated to 37°C. The culture turbidity was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). When OD600 reached ∼2.0, cells were harvested and used to seed 1 L of preheated M9 minimal medium (+100 μg/mL ampicillin) modified to contain 15NH4Cl, replacing NH4Cl as the nitrogen source. Following induction of recombinant protein expression with 1 mM IPTG, this culture was grown overnight. The harvested cells were treated as above with the osmotic shock procedure, and 15N‐labeled α‐synuclein was precipitated with 40% w/v ammonium sulfate as described above prior to anion‐exchange chromatography.

4.4. Chromatographic purification

All versions of recombinant α‐synuclein were purified in essentially the same way, except that 2 mM TCEP was added to buffers when working with the C‐terminal cysteine mutant. Ammonium sulfate protein pellets from 1 L expression culture volume were dissolved (40% w/v) in 90 mL of ice‐cold Q‐Sepharose buffer A (20 mM Tris pH 8.0) then applied to a 30‐mL Q‐Sepharose FF (GE Life Sciences) column pre‐equilibrated with buffer A using an ÄKTA Purifier 100 FPLC system (GE Life Sciences). Unbound proteins were washed off with 10 column‐volumes of buffer A, then α‐synuclein was eluted using a gradient of 0–50% of buffer B (20 mM Tris, 1M NaCl, pH 8.0). Fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE); those containing α‐synuclein were pooled and the protein precipitated again with ammonium sulfate. Protein pellets were then either frozen in liquid nitrogen for long‐term storage at −80°C or further purified by SEC.

For SEC, ammonium sulfate pellets were dissolved at a protein concentration <3 mg/mL in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) for application to a pre‐equilibrated Sephacryl S200 HiPrep 26/60 column. The eluted protein was collected and analyzed using SDS‐PAGE. Fractions containing pure recombinant α‐synuclein were pooled. All samples were quantified spectrophotometrically using Beer's law, measuring the absorbance at 280 nm with a UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 60, Agilent Technologies) and using a theoretical extinction coefficient of 5960M −1 cm−1 (ProtParam).81 Wild type α‐synuclein was dialyzed overnight against MilliQ grade H2O to remove salts and then aliquoted appropriately and lyophilized. The cysteine mutant was concentrated to appropriate values using 3 kDa molecular weight cut‐off concentrators (EMD Millipore), aliquoted into amber, light‐tight 5 mL vials, and lyophilized directly.

4.5. Fluorescent labeling

Lyophilized aliquots of the cysteine mutant were resuspended in 1× PBS, pH 7.0, passed through a 20‐nm filter (Whatman Anotop) to remove spontaneously formed oligomers or fibrils, and then concentrated to 250 μM for optimal fluorescent labeling as described previously.58 Briefly, the protein was incubated with TCEP to reduce the C‐terminal cysteine, then excess TCEP was removed via centrifugal buffer exchange. Thiol‐reactive Oregon Green 488 maleimide in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide was added at a 10:1 molar excess to one aliquot in a light‐tight vial and incubated overnight. A second aliquot of TCEP‐reduced protein was mixed with 3.75 mM of thiol‐reactive trans‐cyclooctene‐(polyethylene glycol)3‐maleimide linker (TPM; Click Chemistry Tools) and transferred to a light‐tight glass vial for mixing overnight, before removing unreacted TPM by buffer exchange as described above. Tetrazine‐labeled Cy5 dye (Click Chemistry Tools) was then added to the second aliquot to a final concentration of 500 μM, and the reaction was incubated overnight at 4°C. In both aliquots, unreacted dye was removed by buffer exchange as above, monitoring removal with a spectrophotometer.

4.6. Fluorescence cross correlation spectroscopy

FCCS experiments were done on a confocal fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss model LSM 510) equipped with 488 and 633‐nm excitation sources. Laser wavelength cutoffs (green 505–540 nm; red 655–710 nm) were established to eliminate cross talk between fluorescence channels. The lasers were collimated into a water‐immersion objective (Carl Zeiss, C‐Apochromat 40×/1.20 W DicIII) and focused on overlapping focal volumes58 in 96‐well glass‐bottom sample cells (CellVis). The system was calibrated by measuring the diffusion coefficients of rhodamine 6G, Oregon green, and Cy5 and comparing to established values.82

Equal volumes of OG‐ or Cy5‐labeled α‐synuclein (125 μL each of 500 μM protein) were mixed in a single tube and incubated at 310 K with continuous shaking at 250 rpm, adding different molar ratios of Fe‐TMPyP to the individual tubes. Two controls were also measured: one without any ligand, and one with EGCG as a known inhibitor of α‐synuclein aggregation in vitro. At the desired measurement time‐points, 1‐μL samples taken from each tube were diluted in PBS to approximately 3 nM, and 50 FCCS measurements were taken per time point. Each experiment was repeated independently in triplicate, and the results averaged.

For each experimental condition, the auto‐correlation curves for individual fluorophores [G g(τ) and G r(τ) for OG and Cy5, respectively] and the dual‐color cross‐correlation curve [G rg(τ)] were fit as described previously.58 Auto‐correlation curves were fit to

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

G(0) is the amplitude of the correlation function, T is the triplet‐state fraction, τ T is the triplet relaxation time of the dye, f 1 is the fraction of signal from free dye, f 2 is the fraction of signal from the α‐synuclein construct, is the diffusion time of the free dye, is the diffusion time of the α‐synuclein construct, α is a parameter reflecting the degree of anomalous diffusion, and w xy/w z is the ratio of the polar and equatorial radii in the confocal volume.83, 84 Cross‐correlation curves were fit with

| (3) |

where G rg(0) is the amplitude of the cross‐correlation function. The parameters w xy/w z = 10, τ T = 4 μs, α = 1, = 46 μs for Oregon green 488, and = 61 μs for Cy5 were fixed during fitting, so that only T, f 1, and varied. The correlation amplitudes were used to calculate the number of single‐labeled (N r, N g) and dual‐labeled (N rg) particles and hence the fraction of all particles that were dual‐colored. Control experiments (Figure S3) showed that Fe‐TMPyP did not quench the Cy5 and OG fluorescence intensity.

4.7. ThT assays

ThT assays of α‐synuclein fibrillization were performed using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek). For each experimental condition, 150 μL of 100‐μM wild type α‐synuclein in PBS containing 15 μM ThT was placed in the wells of a black, sealed, clear‐bottomed 96‐well plate (Greiner Bio‐One) with a 3‐mm acid‐washed glass bead (Sigma‐Aldrich). Microplates were incubated at 37°C with continuous shaking (250 rpm), and ThT fluorescence was quantified at 20‐min intervals by exciting at 440 nm and measuring emission at 490 nm. Three replicates were measured for each time‐point and experimental condition, and the results averaged. Because Fe‐TMPyP absorbs in the same wavelengths as ThT emission,51 ThT fluorescence was corrected for Fe‐TMPyP absorbance by measuring the quenching of the ThT signal in the presence of various molar ratios of ligand (Figure S1). ThT fluorescence saturation value was calculated from the average fluorescence intensity in the 5‐hr window after the end of the growth phase (at 18 hr for 0, 1:10, 1:5, 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1 ligand:protein molar ratios, 23 hr for 5:1, and 25 hr for 10:1), to avoid including effects from dye photobleaching that resulted in a decrease in fluorescence intensity at longer times.

4.8. Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC measurements were made using a Microcal ITC200. 3‐mM Fe‐TMPyP was titrated into 100‐μM α‐synuclein (both in 1× PBS buffer) using an initial 0.2‐μL injection followed by 1‐μL injections at intervals of 2 min, with a stirring rate of 1000 rpm. The temperature was maintained at 25°C. Titrations of ligand into buffer were measured and used for background subtraction before fitting the data. The Bayesian information criterion85 was used to determine that the two‐binding‐site model fit better than models with only one binding site (ΔBIC ≫ 10). Three replicate experiments were performed and the results averaged. Measurements at higher salt concentration were made by adding NaCl into PBS buffer to a total concentration of 274 or 500 mM, making new 3‐mM Fe‐TMPyP and 100‐μM α‐synuclein solutions in these buffers, and titrating the ligand solution into the protein solution under the same conditions as above.

4.9. NMR spectroscopy

15N‐labeled α‐synuclein was resuspended at a concentration of 200 μM in PBS prepared with 10% D2O and containing 100‐μM 4,4‐dimethyl‐4‐silapentane‐1‐sulfonate as an internal chemical‐shift reference. NMR spectroscopy was performed at the NANUC National High Field NMR Facility using a 2.2‐K pumped 800‐MHz Oxford magnet updated to a Bruker Neo‐Advance IV console equipped with a 5‐mm cryoprobe. Two‐dimensional [15N,1H]‐HSQC spectra were acquired at 25°C using the standard Bruker pulse sequence hsqcetf3gpsi with 128 complex points in the 15N dimension and eight scans per increment. The program NMRPipe86 was used to process the data while NMRViewJ87 was used for analysis and assignment of the 2D‐[1H − 15N]‐HSQC peaks. Spectral assignments were based upon the similarity of the observed backbone amide chemical shifts to previous BMRB66 depositions (access codes 19257,67 19337,68 19346,68 25227,69 27074,70 and 2734871).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the contents of this publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.T.W. and N.O.P. designed the experiments. C.D. and C.R.G. produced recombinant protein, performed FCCS, ThT, and ITC experiments. P.M. collected and analyzed NMR data. C.D., C.R.G., and M.T.W wrote the manuscript and all authors edited it.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Quenching of ThT fluorescence by Fe‐TMPyP. ThT fluorescence emission from pre‐formed fibrils was measured at various concentrations of Fe‐TMPyP to determine the extent of quenching by the ligand and the correction factor needed for comparing measurements at different ligand concentrations. Error bars show standard error of the mean of three replicates at each ligand:protein ratio.

Figure S2 Determination of lag phase duration from ThT fluorescence assays. The ThT fluorescence intensity from experiments in (A) a microplate or (B) bulk tubes was fit in the lag phase to a quadratic function (blue) and in the growth phase to an exponential function (red). The intersection of these fits (arrows: ∼7 hr for microplate; ∼53 hr for bulk) yielded the end of the lag phase, as defined previously.90

Figure S3 Fluorescent signals in FCCS are not quenched by Fe‐TMPyP. The fluorescence emission from Cy5‐ (red) and OG‐ (green) labeled α‐synuclein was the same for all Fe‐TMPyP:α‐synuclein molar ratios used in FCCS experiments, showing no quenching by the ligand.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Alberta Prion Research Institute, Alberta Innovates, and the National Research Council of Canada. We thank Dr. Jitendra Kumar for advice regarding efficient 15N‐labelling of the α‐synuclein, as well as Krishna Neupane, Matthew Halma, and Noel Hoffer for helpful discussions.

Dong C, Garen CR, Mercier P, Petersen NO, Woodside MT. Characterizing the inhibition of α‐synuclein oligomerization by a pharmacological chaperone that prevents prion formation by the protein PrP. Protein Science. 2019;28:1690–1702. 10.1002/pro.3684

Chunhua Dong and Craig R. Garen contributed equally to this work.

Significance statement: The effects of an anti‐prion tetrapyrrole on α‐synuclein aggregation were probed experimentally using fluorescent cross‐correlation spectroscopy, ThT fluorescence, isothermal titration calorimetry, and NMR to show that the ligand inhibits oligomerization by binding to α‐synuclein.

Funding information Alberta Innovates; Alberta Prion Research Institute; National Research Council Canada

REFERENCES

- 1. Weinreb PH, Zhen W, Poon AW, Conway KA, Lansbury PT Jr. NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer's disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13709–13715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertoncini CW, Fernandez CO, Griesinger C, Jovin TM, Zweckstetter M. Familial mutants of alpha‐synuclein with increased neurotoxicity have a destabilized conformation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30649–30652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iwai A, Masliah E, Yoshimoto M, et al. The precursor protein of non‐A beta component of Alzheimer's disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron. 1995;14:467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclein: a neuron‐specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2804–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wood SJ, Wypych J, Steavenson S, Louis JC, Citron M, Biere AL. Alpha‐Synuclein fibrillogenesis is nucleation‐dependent implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19509–19512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cremades N, Cohen SI, Deas E, et al. Direct observation of the interconversion of normal and toxic forms of α‐synuclein. Cell. 2012;149:1048–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iljina M, Garcia GA, Horrocks MH, et al. Kinetic model of the aggregation of alpha‐synuclein provides insights into prion‐like spreading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1206–E1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Serpell LC, Berriman J, Jakes R, Goedert M, Crowther RA. Fiber diffraction of synthetic alpha‐synuclein filaments shows amyloid‐like cross‐beta conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4897–4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuttle MD, Comellas G, Nieuwkoop AJ, et al. Solid‐state NMR structure of a pathogenic fibril of full‐length human α‐synuclein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:409–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT Jr. Fibrils formed in vitro from α‐synuclein and two mutant forms linked to Parkinson's disease are typical amyloid. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2552–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. Alpha‐Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6469–6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Volpicelli‐Daley L, Brundin P. Prion‐like propagation of pathology in Parkinson disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;153:321–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goedert M. Filamentous nerve cell inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases: tauopathies and alpha‐synucleinopathies. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1999;354:1101–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baba M, Nakajo S, Tu PH, et al. Aggregation of alpha‐synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:879–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of progress over the last decade. Annu Rev Biochem. 2017;86:27–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clinton LK, Blurton‐Jones M, Myczek K, Trojanowski JQ, LaFerla FM. Synergistic interactions between Abeta, tau, and alpha‐synuclein: acceleration of neuropathology and cognitive decline. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7281–7289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giasson BI, Forman MS, Higuchi M, et al. Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and alpha‐synuclein. Science. 2003;300:636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, et al. Beta‐amyloid peptides enhance alpha‐synuclein accumulation and neuronal deficits in a transgenic mouse model linking Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12245–12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Conway KA, Lee SJ, Rochet J‐C, Ding TT, Williamson RE, Lansbury PT Jr. Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both alpha‐synuclein mutations linked to early‐onset Parkinson's disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta‐peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Outeiro TF, Putcha P, Tetzlaff JE, et al. Formation of toxic oligomeric alpha‐synuclein species in living cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winner B, Jappelli R, Maji SK, Desplats PA, Boyer L, Aigner S. In vivo demonstration that alpha‐synuclein oligomers are toxic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4194–4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fortuna JTS, Gralle M, Beckman D, et al. Brain infusion of α‐synuclein oligomers induces motor and non‐motor Parkinson's disease‐like symptoms in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2017;333:150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fusco G, Chen SW, Williamson PTF, et al. Structural basis of membrane disruption and cellular toxicity by α‐synuclein oligomers. Science. 2017;358:1440–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu T, Bitan G. Modulating self‐assembly of amyloidogenic proteins as a therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases: strategies and mechanisms. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:359–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dehay B, Bourdenx M, Gorry P, et al. Targeting α‐synuclein for treatment of Parkinson's disease: mechanistic and therapeutic considerations. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:855–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wong YC, Krainc D. α‐Synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2017;23:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brundin P, Dave KD, Kordower JH. Therapeutic approaches to target alpha‐synuclein pathology. Exp Neurol. 2017;298:225–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meng X, Munishkina LA, Fink AL, Uversky VN. Molecular mechanisms underlying the flavonoid‐induced inhibition of alpha‐synuclein fibrillation. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8206–8224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu M, Rajamani S, Kaylor J, Han S, Zhou F, Fink AL. The flavonoid baicalein inhibits fibrillation of alpha‐synuclein and disaggregates existing fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26846–26857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ehrnhoefer DE, Bieschke J, Boeddrich A, et al. EGCG redirects amyloidogenic polypeptides into unstructured, off‐pathway oligomers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lamberto GR, Torres‐Monserrat BCW, Salvatella X, Zweckstetter M, Griesinger C, Fernandez CO. Toward the discovery of effective polycyclic inhibitors of alphasynuclein amyloid assembly. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32036–32044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Masuda M, Suzuki N, Taniguchi S, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of alpha‐synuclein filament assembly. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6085–6094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Temsamani H, Krisa S, Decossas‐Mendoza M, Lambert O, Mérillon JM, Richard T. Piceatannol and other wine stilbenes: a pool of inhibitors against α‐synuclein aggregation and cytotoxicity. Nutrients. 2016;8:E367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iljina M, Hong L, Horrocks MH, et al. Nanobodies raised against monomeric ɑ‐synuclein inhibit fibril formation and destabilize toxic oligomeric species. BMC Biol. 2017;15:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schenk DB, Koller M, Ness DK, et al. First‐in‐human assessment of PRX002, an anti‐α‐synuclein monoclonal antibody, in healthy volunteers. Mov Disord. 2017;32:211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sahin C, Lorenzen N, Lemminger L, et al. Antibodies against the C‐terminus of α‐synuclein modulate its fibrillation. Biophys Chem. 2017;220:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rezaeian N, Shirvanizadeh N, Mohammadi S, Nikkhah M, Arab SS. The inhibitory effects of biomimetically designed peptides on α‐synuclein aggregation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;634:96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheruvara H, Allen‐Baume VL, Kad NM, Mason JM. Intracellular screening of a peptide library to derive a potent peptide inhibitor of α‐synuclein aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:7426–7435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Madine J, Doig AJ, Middleton DA. Design of an N‐methylated peptide inhibitor of alpha‐synuclein aggregation guided by solid‐state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7873–7881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abe K, Kobayashi N, Sode K, Ikebukuro K. Peptide ligand screening of alpha‐synuclein aggregation modulators by in silico panning. BMC Bioinf. 2007;8:451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee BI, Lee S, Suh YS, et al. Photoexcited porphyrins as a strong suppressor of beta‐amyloid aggregation and synaptic toxicity. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:11472–11476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tabassum S, Sheikh AM, Yano S, Ikeue T, Handa M, Nagai A. A carboxylated Zn‐phthalocyanine inhibits fibril formation of Alzheimer's amyloid β peptide. FEBS J. 2015;282:463–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Akoury E, Gajda M, Pickhardt M, et al. Inhibition of tau filament formation by conformational modulation. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2853–2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Taniguchi S, Suzuki N, Masuda M, et al. Inhibition of heparin‐induced tau filament formation by phenothiazines, polyphenols, and porphyrins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7614–7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Priola SA, Raines A, Caughey WS. Porphyrin and phthalocyanine antiscrapie compounds. Science. 2000;287:1503–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abdel‐Haq H, Lu M, Cardone F, Liu QG, Puopolo M, Pocchiari M. Efficacy of phthalocyanine tetrasulfonate against mouse‐adapted human prion strains. Arch Virol. 2009;154:1005–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nicoll AJ, Trevitt CR, Tattum MH, et al. Pharmacological chaperone for the structured domain of human prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17610–17615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dee DR, Gupta AN, Anikovskiy M, et al. Phthalocyanine tetrasulfonates bind to multiple sites on natively‐folded prion protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:826–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Massignan T, Cimini S, Stincardini C, et al. A cationic tetrapyrrole inhibits toxic activities of the cellular prion protein. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gupta AN, Neupane K, Rezajooei N, Cortez LM, Sim VL, Woodside MT. Pharmacological chaperone reshapes the energy landscape for folding and aggregation of the prion protein. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wagner J, Ryazanov S, Leonov A, et al. Anle138b: a novel oligomer modulator for disease‐modifying therapy of neurodegenerative diseases such as prion and Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:795–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Andrich K, Bieschke J. The effect of (−)‐epigallo‐catechin‐(3)‐gallate on amyloidogenic proteins suggests a common mechanism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;863:139–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abushakra S, Porsteinsson A, Scheltens P, et al. Clinical effects of tramiprosate in APOE4/4 homozygous patients with mild Alzheimer's disease suggest disease modification potential. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4:149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Collinge J, Gorham M, Hudson F, et al. Safety and efficacy of quinacrine in human prion disease (PRION‐1 study): a patient‐preference trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:334–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li J, Browning S, Mahal SP, Oelschlegel AM, Weissmann C. Darwinian evolution of prions in cell culture. Science. 2010;327:869–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rarbach M, Kettling U, Koltermann A, Eigen M. Dual‐color fluorescence cross‐correlation spectroscopy for monitoring the kinetics of enzyme‐catalyzed reactions. Methods. 2001;24:104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li X, Dong C, Hoffmann M, et al. Early stages of aggregation of engineered α‐synuclein monomers and oligomers in solution. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. LeVine H. Quantification of beta‐sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, et al. EGCG remodels mature alpha‐synuclein and amyloid‐beta fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7710–7715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lorenzen N, Nielsen SB, Yoshimura Y, et al. How epigallocatechin gallate can inhibit α‐synuclein oligomer toxicity in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:21299–21310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Craik DJ, Wilce JA. Studies of protein–ligand interactions by NMR. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;60:195–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Williamson MP. Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2013;73:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bussell R Jr, Eliezer D. Residual structure and dynamics in Parkinson's disease‐associated mutants of alpha‐synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45996–46003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Eliezer D, Kutluay E, Bussell R Jr, Browne G. Conformational properties of alpha‐synuclein in its free and lipid‐associated states. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ulrich EL, Akutsu H, Doreleijers JF, et al. BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D402–D408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Waudby CA, Camilloni C, Fitzpatrick AW, et al. In‐cell NMR characterization of the secondary structure populations of a disordered conformation of α‐synuclein within E. coli cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kang L, Janowska MK, Moriarty GM, Baum J. Mechanistic insight into the relationship between N‐terminal acetylation of α‐synuclein and fibril formation rates by NMR and fluorescence. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Porcari R, Proukakis C, Waudby CA, et al. The H50Q mutation induces a 10‐fold decrease in the solubility of α‐synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:2395–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. El Turk F, De Genst E, Guilliams T, et al. Exploring the role of post‐translational modifications in regulating α‐synuclein interactions by studying the effects of phosphorylation on nanobody binding. Protein Sci. 2018;27:1262–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Murrali MG, Schiavina M, Sainati V, Bermel W, Pierattelli R, Felli IC. 13C APSY‐NMR for sequential assignment of intrinsically disordered proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2018;70:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Fernández CO, Hoyer W, Zweckstetter M, et al. NMR of α‐synuclein‐polyamine complexes elucidates the mechanism and kinetics of induced aggregation. EMBO J. 2004;23:2039–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Antony T, Hoyer W, Cherny D, Heim G, Jovin TM, Subramaniam V. Cellular polyamines promote the aggregation of a‐synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3235–3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Valiente‐Gabioud AA, Miotto MC, Chesta ME, Lombardo V, Binolfi A, Fernández CO. Phthalocyanines as molecular scaffolds to block disease‐associated protein aggregation. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:801–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tatenhorst L, Eckermann K, Dambeck V, et al. Fasudil attenuates aggregation of α‐synuclein in models of Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lamberto GR, Binolfi A, Orcellet ML, et al. Structural and mechanistic basis behind the inhibitory interaction of PcTS on alpha‐synuclein amyloid fibril formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21057–21062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yu H, Liu X, Neupane K, et al. Direct observation of multiple misfolding pathways in a single prion protein molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5283–5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gerum C, Silvers R, Wirmer‐Bartoshek J, Schwalbe H. Unfolded state structure and dyamics influence the fibril formation of human prion protein. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9452–9456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Huang C, Ren G, Zhou H, Wang C. A new method for purification of recombinant human α‐synuclein in Escherichia coli . Protein Expression Purif. 2005;42:173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dong C, Hoffmann M, Li X, et al. Structural characteristics and membrane interactions of tandem α‐synuclein oligomers. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Sanchez JC, Williams KL, Appel RD, Hochstrasser DF. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol. 1999; 112: 531–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kapusta P. Application note: Absolute diffusion coefficients; compilation of reference data for FCS calibration (Rev. 1). Berlin, Germany: PicoQuant, GmbH, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Magde D, Elson EL, Webb WW. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy II. An experimental realization. Biopolymers. 1974;13:29–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lee J, Fujii F, Kim SY, Pack C‐G, Kim SW. Analysis of quantum rod diffusion by polarized fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J Fluoresc. 2014;24:1371–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multi‐dimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Johnson BA. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:313–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Quenching of ThT fluorescence by Fe‐TMPyP. ThT fluorescence emission from pre‐formed fibrils was measured at various concentrations of Fe‐TMPyP to determine the extent of quenching by the ligand and the correction factor needed for comparing measurements at different ligand concentrations. Error bars show standard error of the mean of three replicates at each ligand:protein ratio.

Figure S2 Determination of lag phase duration from ThT fluorescence assays. The ThT fluorescence intensity from experiments in (A) a microplate or (B) bulk tubes was fit in the lag phase to a quadratic function (blue) and in the growth phase to an exponential function (red). The intersection of these fits (arrows: ∼7 hr for microplate; ∼53 hr for bulk) yielded the end of the lag phase, as defined previously.90

Figure S3 Fluorescent signals in FCCS are not quenched by Fe‐TMPyP. The fluorescence emission from Cy5‐ (red) and OG‐ (green) labeled α‐synuclein was the same for all Fe‐TMPyP:α‐synuclein molar ratios used in FCCS experiments, showing no quenching by the ligand.