ABSTRACT

Objective:

To determine whether the topical use of gentamicin reduces periprosthetic joint infection rates in primary total hip arthroplasty (THA).

Methods:

We retrospectively evaluated two cohorts of patients who underwent primary THA in a university hospital, with a minimum of 1-year postoperative follow-up and full clinical, laboratory, and radiological documentation. Patients who underwent operation in the first 59 months of the study period (263 hips) received only intravenous cefazolin as antibiotic prophylaxis (Cef group), and those who underwent operation in the following 43 months (170 hips) received intravenous cefazolin plus topical gentamicin directly applied on the wound as antibiotic prophylaxis (Cef + Gen group). For the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection, we used the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data were analyzed using the Fisher exact test, and p values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results:

Thirteen hips (4.9%) in the Cef group and eight hips (4.7%) in the Cef + Gen group presented periprosthetic joint infection. Statistical analysis revealed no difference between the infection rates (p = 1.0).

Conclusion:

Topical gentamicin as used in this study did not reduce periprosthetic joint infection rates in primary THA. Level of Evidence III, Retrospective comparative study.

Keywords: Infection; Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip; Clinical study; Antibiotic prophylaxis

RESUMO

Objetivo:

Determinar se o uso tópico de gentamicina reduz a taxa de infecção articular periprotética na artroplastia total primária do quadril.

Métodos:

Avaliamos retrospectivamente dois coortes de pacientes submetidos à artroplastia total primária do quadril em um hospital universitário, com seguimento pós-operatório mínimo de 1 ano e completa documentação clínica, laboratorial e radiológica. Os casos operados nos primeiros 59 meses do período do estudo (263 quadris) utilizaram somente a cefazolina por via endovenosa como antibioticoprofilaxia (Grupo Cef). Os casos operados nos 43 meses seguintes (170 quadris) utilizaram a cefazolina por via endovenosa associada à gentamicina tópica aspergida diretamente na ferida operatória como antibioticoprofilaxia (Grupo Cef + Gen). Para o diagnóstico de infecção articular periprotética, utilizamos os critérios do Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Os dados foram submetidos ao teste exato de Fisher, e valor de p menor que 0,05 foi considerado significativo.

Resultados:

Treze quadris apresentaram infecção articular periprotética no Grupo Cef (4,9%) e oito quadris no Grupo Cef + Gen (4,7%). A análise estatística demonstrou não haver diferença entre estas taxas (p=1,0).

Conclusões:

O uso tópico da gentamicina, da maneira como utilizada neste estudo, não reduziu a taxa de infecção articular periprotética na artroplastia total primária do quadril. Nível de evidência III, Estudo comparativo retrospectivo.

Descritores: Infecção, Artroplastia de quadril, Estudo clínico, Antibioticoprofilaxia

INTRODUCTION

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) aims to minimize pain and improve hip joint function, and is considered one of the most effective surgeries in terms of improving patients' quality of life 1 . Data published in the literature demonstrate its increasing use in the last decades, and it is estimated that this trend may grow due to its expanding indications and population aging 2 .

Periprosthetic joint infection is one of the most feared complications of THA and is associated with significant morbidity and high costs of treatment. Several precautions have been proposed to reduce this complication, such as use of pulsatile lavage systems, operating rooms with laminar airflow, body exhaust suits (“space suits”) and topical use of antibiotics 3 – 5 . In 2009, Cavanaugh et al. 6 demonstrated in an in vivo investigation a lower infection rate in orthopedic surgery by the combined use of parenteral cefazolin and topical gentamicin, compared to parenteral cefazolin alone. Motivated by their investigation, we started using topical gentamicin in all THA patients in our hospital.

Our aim is to determine if topical use of gentamicin reduces the periprosthetic joint infection rate in the primary THA, by comparing the infection rate in the period when we used parenteral cefazolin alone as antibiotic prophylaxis, with the most recent period when we started using topical gentamicin in addition to parenteral cefazolin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a comparative retrospective cohort study. The study was performed following the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1995 and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the institution where it was conducted (approval number 2,462,571; January 9th, 2018).

Patient selection

We included all patients who had undergone primary THA during a period of 102 months (8.5 years) in a single hospital, with a minimum postoperative follow-up time of one year and complete clinical, laboratory and radiological documentation. Of a total of 464 primary THA performed in the period, 433 met these requirements. There were no restrictions for inclusion of patients in the study with regard to age, gender, ethnicity, comorbidities, indication for arthroplasty or previous surgeries.

Patients operated on during the first 59 months of the study period used intravenous cefazolin alone as antibiotic prophylaxis (263 hips, Cef group). Patients operated on during the following 43 months of the study period used intravenous cefazolin and topical gentamicin as antibiotic prophylaxis (170 hips, Cef + Gen group).

Data collection and outcomes definition

Data collection from medical records was performed by three authors who were not involved in the treatment of patients. Collected data included patients' gender and age, indication for surgery, type of prosthesis, operative time, occurrence of periprosthetic joint infection and the germ that caused it.

The diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection was based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria 7 , which define that infection is present when, within one year after surgery, there is at least one of the following findings: purulent drainage from a drain that is placed through a stab wound into the joint; organisms isolated from an aseptically obtained culture of joint fluid or tissue; an abscess or other evidence of infection involving the joint on direct examination, during reoperation, or by histopathologic or radiologic examination; diagnosis of joint infection performed by a surgeon or attending physician.

Surgical technique, antibiotic prophylaxis and postoperative care

All patients were operated on by the hip surgery team of the university hospital where the study was performed, using a standardized surgical technique.

When necessary, hair removal in the incision area was performed in the operating room with an electric clipper. Skin preparation was carried out with 10% povidone-iodine-alcohol solution, and an iodine-impregnated incision drape (Ioban®, 3M, St. Paul, MN, USA) was used in the incision area. Patients were positioned in lateral decubitus and surgeries were performed by the direct lateral approach with a 12 to 15-cm long incision. The choice of implant (cemented, hybrid or uncemented) was at the discretion of the surgeon in charge and was based on criteria such as patients' age, bone quality and proximal femoral morphology. Polymethylmethacrylate bone cement used in cemented and hybrid prostheses was always standard, i.e., without antibiotics. The bearing surface used in all cases was highly cross-linked polyethylene/metallic head.

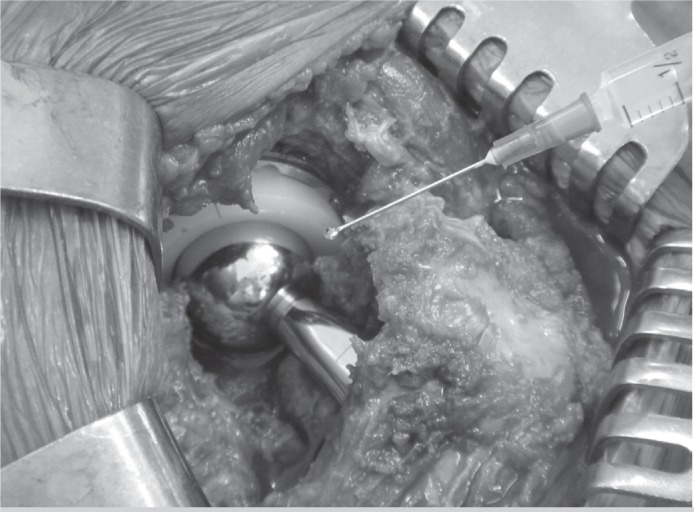

Antibiotic prophylaxis in Cef group was performed with 2g of cefazolin administered by intravenous (IV) injection approximately thirty minutes before the surgical incision and maintained in the postoperative period at a dose of 1g IV every eight hours until completing 48 hours. In Cef + Gen group, in addition to the IV cefazolin in the same protocol as described above, we sprinkled an ampoule of 80mg of liquid gentamicin with a syringe into the surgical wound, immediately before its closure (Figure 1). The postoperative rehabilitation protocol was usually initiated the day after surgery, with isometric exercises and active hip mobilization; gait training was initiated on the second postoperative day. As a general rule, patients were discharged on the third or fourth postoperative day, with information on wound care and suture removal between 10 and 14 days after surgery. Thromboprophylaxis was carried out with compressive elastic stockings and 5,000 IU of unfractionated heparin every 12 hours subcutaneously, for four weeks. All patients were followed up postoperatively for clinical and radiographic assessment at one month, two months, six months, twelve months and annually thereafter.

Figure 1. Liquid gentamicin sprinkled directly into the surgical wound, immediately before its closure.

Statistical analysis

Data sets were evaluated by means of a descriptive statistics, in which it was possible to characterize the cohorts regarding the variables collected. Data were submitted to Fisher's exact test to evaluate the association between categorical variables, and to Student's t-test for comparison of quantitative variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic and surgical data are presented in Table 1. Statistical analysis found that distribution of the variables gender, indication for surgery and type of prosthesis, as well as mean age were similar between the groups. Mean operative time presented a significant difference between groups, being higher in Cef group (p=0.002). Periprosthetic joint infection occurred in thirteen hips in Cef group (4.9%) and in eight hips in Cef + Gen group (4.7%). There was no significant difference between these rates (p=1.0; Table 2).

Table 1. Demographic and surgical characteristics of patients.

| Variable | Cef group | Cef + Gen group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender male / female (percentage) |

137 / 126 (52.1% / 47.9%) |

94 / 76 (55.3% / 44.7%) |

p*=0.55 |

| Mean age in years (range; SD) |

64.7 (34 − 81; 6.9) |

63.9 (30 − 82; 8.8) |

p**=0.26 |

| Indication for surgery | |||

| Prim OA / Sec OA / FNF (percentage) |

181 / 65 / 17 (68.8% / 24.7% / 6.5%) |

108 / 50 / 12 (63.5% / 29.4% / 7.1%) |

p*=0.49 |

| Type of prosthesis | |||

| cem / hyb / uncem (percentage) |

47 / 114 / 102 (17.9% / 43.3% / 38.8%) |

23 / 67 / 80 (13.5% / 39.4% / 47.1%) |

p*=0.19 |

| Mean operative time in minutes (range; SD) |

135.9 (90 − 190; 17.6) |

129.9 (85 − 210; 21.1) |

p**=0.002 |

SD: standard deviation; Prim OA: primary osteoarthritis; Sec OA: secondary osteoarthritis; FNF: femoral neck fracture; cem: cemented; hyb: hybrid; uncem: uncemented;

Fisher's exact test;

Student's t-test.

Table 2. Periprosthetic joint infection rate in the groups.

| Group | Infection | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Cef + Gen | 162 (95.3%) | 8 (4.7%) | 1.0 |

| Cef | 250 (95.1%) | 13 (4.9%) | |

Fisher's exact test.

The germs that caused infections in Cef + Gen group were S. epidermidis (two cases), E. cloacae (two cases), S. aureus (one case), P. aeruginosa (one case), A. baumannii (one case) and S. agalactiae (one case). In Cef group, the germs were S. aureus (four cases), S. epidermidis (three cases), E. coli (two cases), S. haemolyticus (one case), P. mirabilis (one case), E. cloacae (one case) and P. aeruginosa (one case). Thus, there was a predominance of infections caused by Gram-negative germs in Cef + Gen group and a predominance of infections caused by Gram-positive germs in Cef group, but without significant difference (Table 3).

Table 3. Germ distribution in the groups.

| Group | Germ | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative | Gram-positive | ||

| Cef + Gen | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.39 |

| Cef | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (61.5%) | |

Fisher's exact test.

In Cef + Gen group, mean operative time for patients who developed periprosthetic joint infection was 165 minutes, but for those who did not develop periprosthetic joint infection was 128.2 minutes, demonstrating a significant difference (p<0.0001). The same pattern was observed in Cef group, where the mean operative times for patients who developed and did not develop periprosthetic joint infection were respectively 157.3 minutes and 134.8 minutes (p<0.0001). Likewise, comparison of the mean operative time for all cases who developed and did not develop periprosthetic joint infection, without distinction between groups, presented significant difference (160.2 minutes and 132.2 minutes, respectively; p<0.0001). The data are shown in Table 4. There was no association between the type of prosthesis and periprosthetic joint infection, either in Cef + Gen group (p=0.16) or in Cef group (p=0.75). Analysis of this association in all cases, without distinction between groups, also did not present statistical significance (p=0.27). The data are shown in Table 5.

Table 4. Association between operative time and periprosthetic joint infection.

| Group | Infection | n | Mean operative time in minutes (range; SD) |

Difference in minutes (95% CI) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cef + Gen | No | 162 | 128.2 (85 − 175; 19.2) | 36.8 (23.9 − 49.6) |

<0.0001 |

| Yes | 8 | 165 (130 − 210; 27.9) | |||

| Cef | No | 250 | 134.8 (90 − 190; 16.7) | 22.5 (12.4 − 32.5) |

<0.0001 |

| Yes | 13 | 157.3 (120 − 190; 21.1) | |||

| All cases | No | 412 | 132.2 (85 − 190; 18) | 28 (19.9 − 36.1) |

<0.0001 |

| Yes | 21 | 160.2 (120 − 210; 23.5) |

n: number of cases; SD: standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval;

Student's t-test.

Table 5. Association between type of prosthesis and periprosthetic joint infection.

| Cef + Gen group |

Cef group |

All cases |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of prosthesis | Infection | Infection | Infection | |||

| No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

|

| Cemented | 20 (87%) |

3 (13%) |

44 (93.6%) |

3 (6.4%) |

64 (91.4%) |

6 (8.6%) |

| Hybrid | 65 (97%) |

2 (3%) |

108 (94.7%) |

6 (5.3%) |

173 (95.6%) |

8 (4.4%) |

| Uncemented | 77 (96.2%) |

3 (3.8%) |

98 (96.1%) |

4 (3.9%) |

175 (96.2%) |

7 (3.8%) |

| p-value*: 0.16 | p-value*: 0.75 | p-value*: 0.27 | ||||

Fisher's exact test.

Regarding the association between indication for surgery and periprosthetic joint infection, there was no statistical significance in Cef + Gen group (p=0.06), but statistical significance was found in Cef group, with femoral neck fracture cases presenting a higher infection rate (p=0.02). Analysis of this association in all cases, without distinction between groups, also presented statistical significance and, once again, femoral neck fracture cases presented the highest infection rate (p = 0.003). The data are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Association between indication for surgery and periprosthetic joint infection.

| Cef + Gen group |

Cef group |

All cases |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication for surgery | Infection | Infection | Infection | |||

| No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

|

| Prim OA | 105 (97.2%) |

3 (2.8%) |

176 (97.2%) |

5 (2.8%) |

281 (97.2%) |

8 (2.8%) |

| Sec OA | 47 (94%) |

3 (6%) |

60 (92.3%) |

5 (7.7%) |

107 (93%) |

8 (7%) |

| FNF | 10 (83.3%) |

2 (16.7%) |

14 (82.4%) |

3 (17.6%) |

24 (82.8%) |

5 (17.2%) |

| p-value*: 0.06 | p-value*: 0.02 | p-value*: 0.003 | ||||

Prim OA: primary osteoarthritis; Sec OA: secondary osteoarthritis; FNF: femoral neck fracture;

Fisher's exact test.

DISCUSSION

It is estimated that the cost of treatment of a periprosthetic joint infection is four to five times higher than the cost of an uncomplicated primary arthroplasty 8 , 9 . In addition to the direct financial impact associated to the treatment of an infected THA, there are indirect impacts related to loss of patients' productivity. Even with successful treatment, patients often require 6 to 18 months to recover the function they had before the onset of infection, and in some cases the patient may never recover the same functional levels 10 . The criteria used for the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection in this study were proposed by the CDC 7 in 1992 and are used in the literature until the present time 11 – 13 . More recently, in 2013, the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) published an international consensus for the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection 14 . We did not use the MSIS criteria in this study because a significant part of our series had been operated before 2013 and, at that time, we had not yet incorporated all the laboratory tests proposed by this international consensus for the investigation of periprosthetic joint infection. It is interesting to note that Honkanen et al. 15 recently compared the concordance between these two sets of diagnostic criteria in a tertiary orthopedic hospital and reported that 18% of the arthroplasties diagnosed as infected according to the CDC criteria were not considered infected according to the MSIS criteria, demonstrating that the old criteria may overestimate the real rate of periprosthetic joint infection or that the new criteria may underestimate it.

The periprosthetic joint infection rate in primary THA in our hospital are within the values reported by other Brazilian authors, ranging from 0.98% to 6.5% 11 , 16 – 18 , but are above the rates reported by North American and European authors, ranging from 0.3% to 2.3% 4 , 9 , 19 . Besides possible factors directly related to the patient, the fact that we do not use body exhaust suits and the circulation of several persons in the operating room, typical of a teaching hospital such as ours, may be factors related to these higher rates 20 .

Topical use of antibiotics in orthopedic surgeries can be accomplished by adding it to irrigation solution, bone grafts, bone substitutes, bone cement or by applying it directly to the operative wound in the form of powder or liquid, as in our case. Our results demonstrated that there was no reduction of periprosthetic joint infection rate in primary THA with topical use of gentamicin in the operative wound.

From a theoretical point of view, topical use of antibiotics in orthopedic surgeries is an interesting strategy, because it provides high concentration of the antibiotic at the surgical site, with fewer systemic adverse effects. This strategy has been studied for several years, with conflicting results. In 2011, O'Neill et al. 21 and also Sweet, Roh and Silva 22 reported a reduction in the surgical site infection rate with topical application of vancomycin powder in patients submitted to spinal arthrodesis. Parvizi et al. 4 reported that the use of antibiotic-impregnated cement reduces the rate of periprosthetic joint infection by approximately 50% in primary THA. Romanò et al. 23 in a multicenter study demonstrated a reduction in the rate of periprosthetic joint infection in THA with application of an antibiotic-loaded hydrogel coating onto the surface of the implants. Evidence on the efficacy of topical use of vancomycin 24 and gentamicin 6 to reduce the surgical site infection rate in orthopedic surgeries has also been found in animal models. On the other hand, Tubaki, Rajasekaran and Shetty 25 in 2013 found no reduction in surgical site infection rate with topical application of vancomycin powder in patients undergoing spinal surgery. Schiavone Panni et al. 26 reported in their systematic review that the use of antibiotic-loaded bone cement does not reduce the rate of periprosthetic joint infection in primary total knee arthroplasty. Finally, the CDC guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection published in 2017 declares that intraoperative antimicrobial irrigation for the prevention of surgical site infection is an unresolved issue 27 .

All the demographic characteristics between groups were similar. Mean operative time was the only surgical variable that showed difference between groups (six minutes shorter in Cef + Gen group); despite the small nominal value, this difference was statistically significant (p=0.002). Therefore, even with a mean shorter operative time, Cef + Gen group did not present a lower periprosthetic joint infection rate. We can argue from a logical point of view that this finding would reinforce the hypothesis of ineffectiveness of topical gentamicin in reducing the periprosthetic joint infection rate, since the literature shows that a shorter surgical time is associated with lower infection rates 28 , a fact that was also observed in our data.

We also found a higher rate of periprosthetic joint infection in patients operated due to a femoral neck fracture, and the association between these two circumstances was statistically significant in Cef group and again when patients were evaluated all together. The higher incidence of periprosthetic joint infection in patients with femoral neck fracture has been previously reported by other authors 28 and presumably occurs due to local and systemic reactions to trauma and because these surgeries are performed on an urgent basis, when patients are frequently not in the best clinical conditions.

The study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective study based on information collected from patients' medical records, and therefore, depends on the accuracy of this information. Second, the groups were not evaluated for the presence of factors that could influence the periprosthetic joint infection rate, such as body mass index, associated systemic diseases (diabetes, autoimmune diseases), previous hip surgeries and physical status. Finally, the number of patients studied is relatively small.

CONCLUSION

Topical application of gentamicin as used in this study did not reduce the periprosthetic joint infection rate in primary THA.

Footnotes

This work was developed at the Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

REFERÊNCIAS

- 1.Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(5):963–974. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block JE, Stubbs HA. Reducing the risk of deep wound infection in primary joint arthroplasty with antibiotic bone cement. Orthopedics. 2005;28(11):1334–1345. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20051101-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parvizi J, Saleh KJ, Ragland PS, Pour AE, Mont MA. Efficacy of antibiotic-impregnated cement in total hip replacement. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(3):335–341. doi: 10.1080/17453670710015229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Frampton C, Wyatt MC. Does the use of laminar flow and space suits reduce early deep infection after total hip and knee replacement?: the ten-year results of the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):85–90. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.24862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavanaugh DL, Berry J, Yarboro SR, Dahners LE. Better prophylaxis against surgical site infection with local as well as systemic antibiotics. An in vivo study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1907–1912. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13(10):606–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozic KJ, Ries MD. The impact of infection after total hip arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1746–1751. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapadia BH, Berg RA, Daley JA, Fritz J, Bhave A, Mont MA. Periprosthetic joint infection. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):386–394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61798-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malizos KN, Poultsides LA. The socio-economic burden of musculoskeletal infections. In: Meani E, Romanò C, Crosby L, Hofmann G, editors. Infection and local treatment in orthopedic surgery. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2007. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinto CZS, Alpendre FT, Stier CJN, Maziero ECS, de Alencar PG, Cruz EDA. Characterization of hip and knee arthroplasties and factors associated with infection. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;50(6):694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelstein R, Eluk O, Mashiach T, Levin D, Peskin B, Nirenberg G, et al. Reducing surgical site infections following total hip and knee arthroplasty: an Israeli experience. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(3):219–225. doi: 10.1007/s12306-017-0471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baratz MD, Hallmark R, Odum SM, Springer BD. Twenty Percent of Patients May Remain Colonized With Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Despite a Decolonization Protocol in Patients Undergoing Elective Total Joint Arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(7):2283–2290. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parvizi J, Gehrke T. International Consensus Group on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Definition of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1331–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honkanen M, Jämsen E, Karppelin M, Huttunen R, Lyytikäinen O, Syrjänen J. Concordance between the old and new diagnostic criteria for periprosthetic joint infection. Infection. 2017;45(5):637–643. doi: 10.1007/s15010-017-1038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima ALLM, Barone AA. Hospital infections in 46 patients submitted to total hip replacement. Acta Ortop Bras. 2001;9(1):36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ercole FF, Chianca TC. Surgical wound infection in patients treated with hip arthroplasty. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2002;10(2):157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Dolinger EJ, de Souza GM, de Melo GB, Filho PP. Surgical site infections in primary total hip and knee replacement surgeries, hemiarthroplasties, and osteosyntheses at a Brazilian university hospital. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(3):246–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1710–1715. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0209-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picado CH, Garcia FL, Chagas MV, Jr, Toquetao FG. Accuracy of intraoperative cultures in primary total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int. 2008;18(1):46–50. doi: 10.5301/hip.2008.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Neill KR, Smith JG, Abtahi AM, Archer KR, Spengler DM, McGirt MJ, et al. Reduced surgical site infections in patients undergoing posterior spinal stabilization of traumatic injuries using vancomycin powder. Spine J. 2011;11(7):641–646. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sweet FA, Roh M, Sliva C. Intrawound application of vancomycin for prophylaxis in instrumented thoracolumbar fusions: efficacy, drug levels, and patient outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36(24):2084–2088. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ff2cb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romanò CL, Malizos K, Capuano N, Mezzoprete R, D'Arienzo M, Van Der Straeten C, et al. Does an Antibiotic-Loaded Hydrogel Coating Reduce Early Post-Surgical Infection After Joint Arthroplasty? J Bone Jt Infect. 2016;1:34–41. doi: 10.7150/jbji.15986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zebala LP, Chuntarapas T, Kelly MP, Talcott M, Greco S, Riew KD. Intrawound vancomycin powder eradicates surgical wound contamination: an in vivo rabbit study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):46–51. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tubaki VR, Rajasekaran S, Shetty AP. Effects of using intravenous antibiotic only versus local intrawound vancomycin antibiotic powder application in addition to intravenous antibiotics on postoperative infection in spine surgery in 907 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(25):2149–2155. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiavone Panni A, Corona K, Giulianelli M, Mazzitelli G, Del Regno C, Vasso M. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement reduces risk of infections in primary total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(10):3168–3174. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, Leas B, Stone EC, Kelz RR, et al. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784–791. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridgeway S, Wilson J, Charlet A, Kafatos G, Pearson A, Coello R. Infection of the surgical site after arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(6):844–850. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B6.15121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]