Abstract

Aim

This paper reports on the incorporation of oleic acid (OA) within nanostructured lipid carriers (OA-NLC) to improve the anti-inflammatory effects in the presence of albumin.

Materials and methods

NLCs produced via hot high-shear homogenization/ultrasonication were characterized in terms of particle size, zeta potential, and toxicity. We examined the effects of OA-NLC on neutrophil activities. Dermatologic therapeutic potential was also elucidated by using a murine model of leukotriene B4-induced skin inflammation.

Results

In the presence of albumin, OA-NLC but not free OA inhibited superoxide generation and elastase release. Topical administration of OA-NLC alleviated neutrophil infiltration and severity of skin inflammation.

Conclusion

OA incorporated within NLC can overcome the interference of albumin, which would undermine the anti-inflammatory effects of OA. OA-NLC has potential therapeutic effects in topical ointments.

Keywords: oleic acid, nanostructured lipid carrier, neutrophil, reactive oxygen species, superoxide, elastase

Introduction

Fatty acids (FAs) are a major source of energy in mammalian bodies. They also have modulatory effects on immune responses and physiological functions.1 FAs have been shown to stimulate or inhibit many inflammatory molecules (eg, reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokines, and antibodies) and bioactive lipid mediators (eg, arachidonic acid (AA), linoleic acid (LA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)).1–4 Oleic acid (OA; cis-9-octadecenoic acid), a monounsaturated omega-9 fatty acid (C18:1, n-9), is the most abundant fatty acid in healthy individuals, presenting in adipose tissue, plasma, and cell membranes.5,6 There is a growing body of evidence which indicates that OA is beneficial to blood pressure control and that it helps to slow the progress of cancer and inflammatory diseases.7–10 However, the role of OA in inflammatory responses remains controversial. Indeed, a number of studies have reported the anti-inflammatory of OA;11 however, other studies have contradicted these claims. Nonetheless, most of the conflicting findings can be attributed to differences in methodology or OA concentration.11

Neutrophils constitute the major component of the human immune system, playing a critical role in defending against invading pathogens. Nonetheless, excessive neutrophil activation can lead to tissue damage. In a previous study, we reported that OA inhibits superoxide anion and elastase release from activated neutrophils by blocking Ca2+ mobilization through the modulation of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase.12 However, higher concentrations of OA were required to suppress neutrophil effector functions in the presence of albumin.12 This suggests that, to inhibit neutrophil activity, OA concentrations must exceed the FA binding capacity of albumin. The fact that FAs with long non-polar hydrocarbon chains are hydrophobic (ie, minimally water soluble) means that they must bind with albumin in order to be transported through vascular and interstitial compartments. However, it is possible that this binding may hampers the cellular effects of FA.

There is growing interest in the application of nanotechnology in the fields of molecular and cellular biology. Lipid-based nanoparticles have been developed as drug carriers with a range of therapeutic advantages, including enhanced drug stability and bioavailability, minimal systemic toxicity, prolonged circulation time, and improved biocompatibility.13,14 Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) are the latest generation of lipid nanoparticle drug carrier system.15,16 They are composed of mixtures of liquid and solid lipids that are biodegradable and biocompatible. Unlike solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), which have only a solid matrix, NLCs are characterized by the enhanced imperfections that result from the incorporation of liquid oil within the solid lipid core matrix. The imperfections increase the hydrophobic drug loading capacity and reduce the likelihood of drug expulsion.15,16

In a previous study, we reported that unsaturated FAs (USFAs) regulate the inflammatory responses of neutrophils but, in the presence of albumin, inhibitory effects were eliminated. In this current study, we adopted a well-established isolated human neutrophil model to test the hypothesis that incorporating OA within NLC (OA-NLC) could enhance its anti-neutrophilic inflammation functions in the presence of albumin. We also sought to elucidate the mechanism by which OA-NLC regulates neutrophil effector activity. We then examined the physicochemical properties of NLC, such as the size, and zeta potential, as well as the potential for toxicity. An animal model of leukotriene B4 (LTB4)-induced skin inflammation was used to evaluate the therapeutic effects of OA-NLC when delivered topically.

Materials and methods

NLC preparation

NLCs were produced via hot high-shear homogenization followed by ultrasonication in accordance with previously reported methods, albeit with minor modifications.17 The lipid matrix, which consists of 6% palmityl palpitates, 1% soy phosphatidylcholine, and 6% OA, was heated up to 85 °C to form a uniform oil phase. The aqueous solution, which contained the hydrophilic surfactant pluronic F68 (3.5%) and ddH2O (83.5%), was also heated to 85 °C. Subsequently, the hot lipid matrix was gradually dispersed in the aqueous solution under the effects of high-shear homogenization (Pro250, Pro Scientific) at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The resulting mixture was then ultrasonicated using a probe-type sonicator (VCX600, Sonics and Materials, Newtown, CT, USA) for 15 min duration at 35 W and 20 amplitudes without intermittent on/off cycle to obtain the final product.

Determining particle size and surface charge

The average particle size of the NLCs was determined via photon correlation spectroscopy, and surface charge (zeta potential) was measured via particle electrophoretic light scattering using a laser-scattering zetasizer (Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) at 25 °C. The nanoparticles were diluted 100-fold with ddH2O before measurements. All measurements were repeated three times per sample.

Observation of morphology using transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The shape and size of OA–NLC were visualized using a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi H-7500). For this, a drop of OA–NLC that had been diluted 100-fold with ddH2O was applied to a 200-mesh copper grid coated with formvar/carbon film (Agar Scientific, UK), and then subjected to negative staining with 1% phosphotungstic acid. The sample was subsequently dried in the air prior to observation under TEM.

Determination of OA entrapment efficiency (EE) in NLC

Entrapment efficiency was used to indicate the percentage of OA which is successfully entrapped into nanoparticles. It is calculated as follows:

The EE of OA was determined by first separating the OA from the NLC via ultracentrifugation at 48,000×g and 4 °C for 40 min and then measuring the free OA in the supernatant using high-performance liquid chromatography. Because OA is short of significant chromophore, derivatization of OA with 2-bromoacetophenone was used to enhance its detectability.18 Briefly, OA standard or OA separated from OA-NLC were dissolved in 0.5 mL acetonitrile, and then an excess amount of K2CO3 powder was added. Subsequently, the derivatization procedure was started by adding 2-bromo-2-acetonaphthone (200 mg) and hexaoxacyclo octadecane (100 mg) in 20 mL acetonitrile to the sample, and then sonicated at 55 °C for 1 h. Samples were analyzed by using a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system, which includes a pump (PU-1580, Jasco), a sampler (AS-1555-10, Jasco), a UV detector (UV-1575, Jasco), and a 25-cm-long, 4.6-mm inner diameter C18 column (Supelco Analytical). The mobile phase consisted of ddH2O (7%) and methanol (93%) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The UV detector was set a wavelength of 250 nm.

Human neutrophil isolation

Human neutrophils were purified from peripheral venous blood within 3 h after collection from healthy volunteers.19 All donors (aged 20–30 years) were informed of the risks associated with blood collection and provided written consent before blood was collected. All donors also declared that they did not have any systemic disease. Blood was layered on a density gradient using dextran sedimentation and Ficoll–Hypaque centrifugation. The neutrophil-rich layer was then collected, and contaminated red blood cells were disrupted via hypotonic lysis. Wright–Giemsa staining and trypan blue exclusion were respectively used to confirm the purity (≥99%) and viability (≥95%) of neutrophils. The isolated neutrophils were suspended in pH 7.4 Ca2+-free Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) with or without 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 4 °C prior to each experiment. This study was conducted in accordance with a protocol for human subjects that was approved by the institutional review board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Assessment of cytotoxicity

To assess the safety of the NLC formulations used in this study, the viability of NLC-treated neutrophils was determined by measuring the amount of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released from ruptured cells. LDH release was measured using a CytoTox 96 assay kit (Promega). Briefly, neutrophils (6×105 cells/mL) were first treated with various concentrations of OA or OA-NLC for 17 min. The cells were then centrifuged at 200 g at 4 °C for 8 min, whereupon LDH assay reagents were added to the supernatant. Measured colorimetric signal were presented as a percentage of total LDH activity, as determined by measuring the fluorescence of lysed neutrophils treated with 0.1% Triton X-100.

Assessment of superoxide generation

Superoxide generation assays were conducted by measuring the reduction of ferricytochrome c.19 For this, neutrophils (6×105 cells/mL) were suspended in HBSS that contained CaCl2 (1 mM) and ferricytochrome c (0.5 mg/mL) at 37 °C. The cells were then pretreated with vehicle, OA, or OA-NLC for 5 min, followed by the addition of cytochalasin B (1 μg/mL) for 3 min and then fMLF (0.1 μM) to activate the neutrophils. The reduction of ferricytochrome c was monitored by measuring changes in absorbance at 550 nm using a spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-3010, Tokyo, Japan). Control groups contained all the components of the assay buffer and additional superoxide dismutase (100 U/mL) for correction the ferricytochrome c reduction induced by agents other than superoxide.19

Luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence assay

Total ROS released from the neutrophils was evaluated by using the luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence method. Human neutrophils (2×106 cells/mL) were preincubated with luminol (37.5 μM) and horseradish peroxidase (6 U/mL) at 37 °C for 5 min. before being treated with vehicle, OA, or OA-NLC for 5 min. Cytochalasin B (0.5 μg/mL) and fMLF (0.1 μM) were then used to induce respiratory burst in neutrophils. Chemiluminescence was detected using a Tecan Infinite F200 Pro 96-well chemiluminometer (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Elastase release

Upon activation, neutrophils release antimicrobial proteins in a process referred to as degranulation. Elastase release was measured spectrophotometrically using a synthetic elastase substrate, methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-p-nitroanilide.19,20 Human neutrophils suspensions (6×105 cells/mL) were preincubated in HBSS containing CaCl2 (1 mM) and elastase substrate (0.1 mM) at 37 °C. The cells were then treated with vehicle, OA, or OA-NLC (5–100 μM) for 5 min prior to stimulation with cytochalasin B (0.5 μg/mL) and fMLF (0.1 μM) or cytochalasin B (0.5 μg/mL) and LTB4 (0.1 μM). The extent of p-nitrophenol spectrophotometrically was continuously measured at 405 nm using a spectrometer (Hitachi U-3010).

Observation of NLC uptake by neutrophils

The uptake of OA-NLC by neutrophils was monitored by producing fluorescent-labelled OA-NLCs via the addition of rhodamine 800 (0.1 mg/mL) in lipid phase during OA-NLC preparation. For this, human neutrophils (1.8×107 cells/mL) were labeled with Dil-C12 fluorescent dye. These labeled cells were co-incubated with labeled OA-NLC at 37 °C for 5 min. The intracellular fluorescence signal was then observed and localized by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM).

Determination of cytosolic Ca2+

Isolated human neutrophils were suspended in HBSS containing Fluo 3-AM (2 μM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a density of 3×106 cells/mL at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells were then re-suspended in HBSS containing CaCl2 (1 mM). The loaded cells were subsequently treated with vehicle, OA, or OA-NLC for 5 min, before undergoing stimulation with fMLF (0.1 μM). Intracellular free Ca2+ measurements were conducted using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi F-4500) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm. The maximum and minimum fluorescence values were respectively obtained by adding 0.05% Triton X-100 and 20 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid.

Induction of inflammatory responses in mice skin

LTB4, one of the most potent neutrophil chemotactic compounds,21 was used to induce skin inflammation in our in-vivo mice model. For this, male BALB/c mice (8 weeks old; weighing 18–20 g) (Lasco, Taipei, Taiwan) were housed in a pathogen-free environment at Chang Gung University (CGU). OA (in ethanol) and OA-NLC (in ddH2O) were applied topically to both ear of the mice for a period of 30 min, followed by the topical application of LTB4 (0.5 μg/mL, in ethanol). One day after inducing inflammation, the mice were anaesthetized by inhalation of 1–2% isoflurane to obtain skin tissue samples (6 mm in diameter). All procedures performed on the animals were in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of CGU.

Skin histology and MPO assay

For histological analysis, the skin samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sliced using a microtome at a thickness of 3 μm, mounted on glass slides, and then stained using hematoxylin and eosin (HE). The histological morphology of skin samples were observed using a microscope (Eclipse TS100; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). MPO activity was used to indicate the infiltration of neutrophils. For this, skin samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C until MPO activity assays were performed. After thawing, the samples were immersed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) containing hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (0.5%) before undergoing sonication and centrifugation. The homogenates were then suspended in PBS containing o-dianisidine hydrochloride (0.167 mg/mL) and hydrogen peroxide (0.0005%, Sigma). MPO activity was evaluated by spectrophotometric analysis to monitor changes in absorbance at 460 nm. Final MPO activity values were normalized to the corresponding protein concentration.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SEM. For statistical analysis, we performed Student’s t-tests using SigmaPlot software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). In examining differences among groups, the p-value which were lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

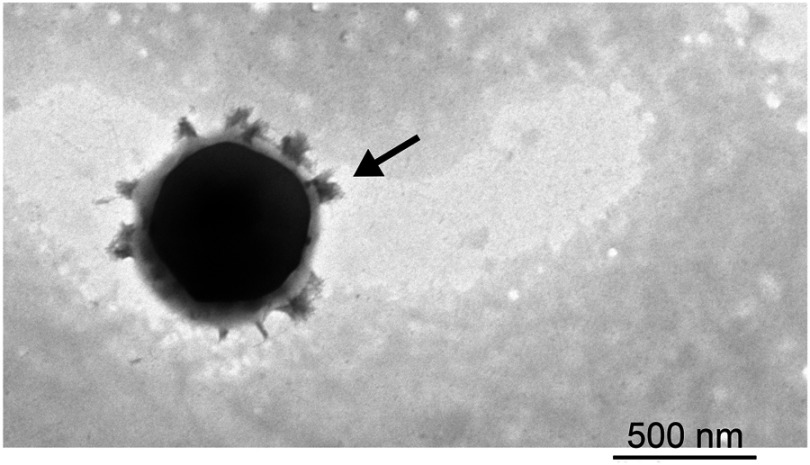

Characterization of NLC

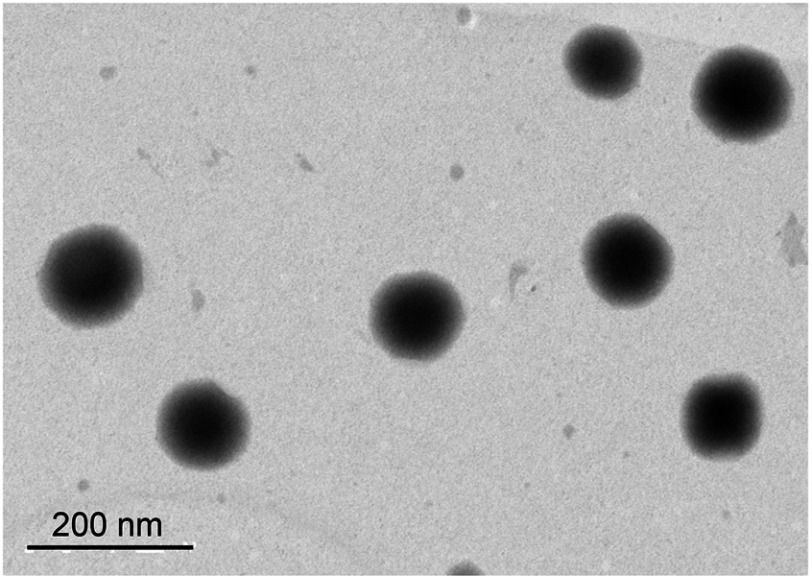

The morphology, particle size, zeta potential, and drug EE values of NLC are presented in Figure 1 and Table 1. The mean size of all nanoparticles ranges from 175 to 210 nm. The NLC nanoparticles presented a negative zeta potential of approximately −40 mV. TEM images revealed that all particles were spherical with a smooth surface and did not agglomerate. Finally, EE values obtained using HPLC revealed that nearly 100% of OA were encapsulated in the nanoparticles.

Figure 1.

Transmission electron micrograph images of OA-NLC.

Notes: OA–NLC was applied to a copper grid coated with formvar/carbon film, and then stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid. The sample was subsequently dried in the air prior to observation under TEM. Scale bar, 200 nm. Representative data from four independent experiments are shown.

Abbreviations: OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Table 1.

The physicochemical characteristics of OA-NLC in the absence or presence of albumin

| Size (nm) | PI | ZP (mV) | EE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without albumin | ||||

| OA-NLC | 208.26 ± 0.93 | 0.19 ± 0.93 | −40.59 ± 1.14 | 100.00 ± 0.00 |

| With albumin | ||||

| OA-NLC | 421.72 ± 0.83 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | −12.61 ± 0.06 | N/A |

Notes: The particle size, polydispersity index, zeta potential, and drug EE values nanoparticles are presented.

Abbreviations: OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carrier; PI, polydispersity index; ZP, zeta potential; EE, entrapment efficiency; N/A, not applicable.

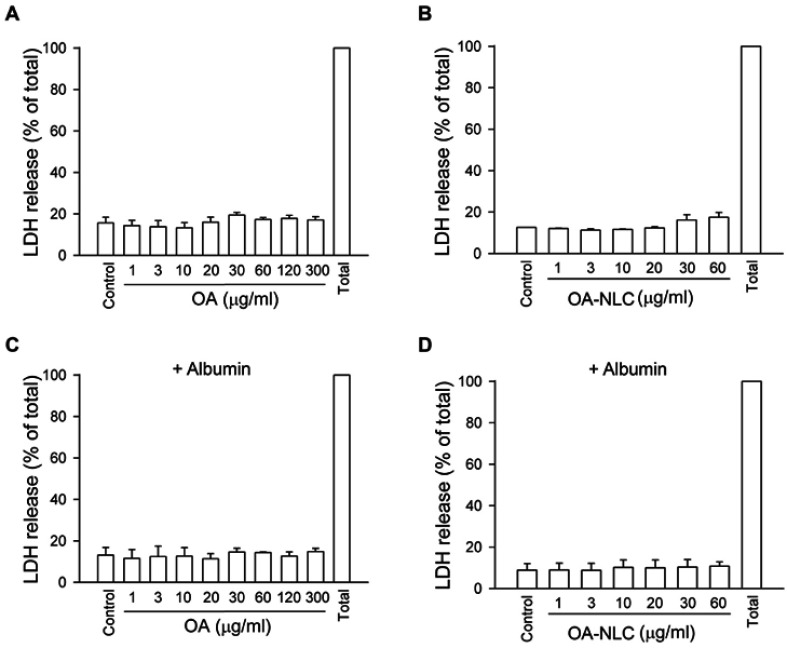

Cytotoxic effect of OA and OA-NLC

LDH is commonly used as a cell death marker, as it is released when the cell membrane is disrupted. Our results revealed that neither OA nor OA-NLC led to LDH release when they are co-incubated with neutrophils at a concentration of 1–30 μg/mL for 15 min in the presence or absence of BSA (Figure 2). This suggests that neither OA nor OA-NLC is cytotoxic in this study.

Figure 2.

OA and OA-NLC do not have cytotoxicity effect.

Notes: Neutrophils (6×105 cells/mL) were treated with various concentrations of OA (A, C) or OA-NLC (B, D) for 17 min in the absence (A, B) or presence (C, D) of 0.1% BSA. LDH activity was assessed with a commercial LDH assay kit. Measured colorimetric signal was presented as a percentage of total LDH activity, as determined by measuring the fluorescence of lysed neutrophils treated with 0.1% Triton X-100. Data are expressed as mean standard error of the mean, n=4.

Abbreviations: OA, oleic acid; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers; BSA, bovine serum albumin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

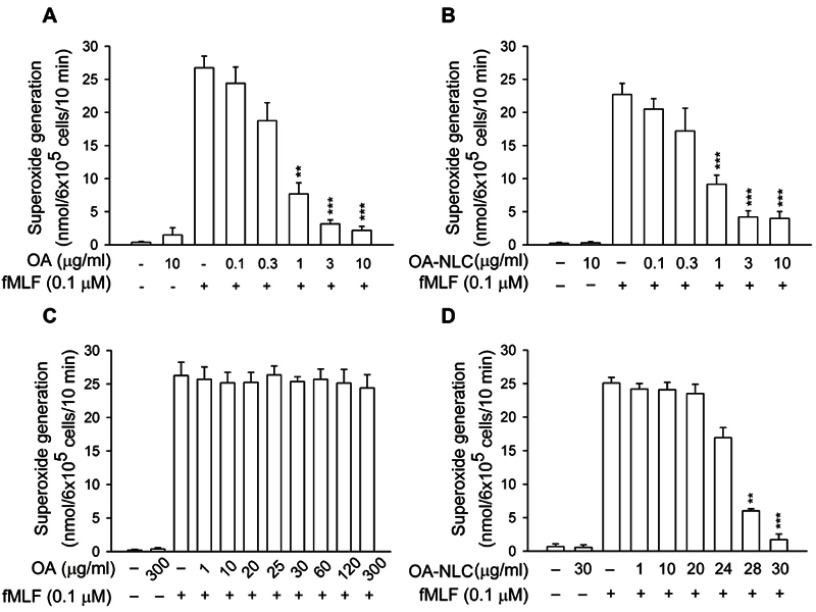

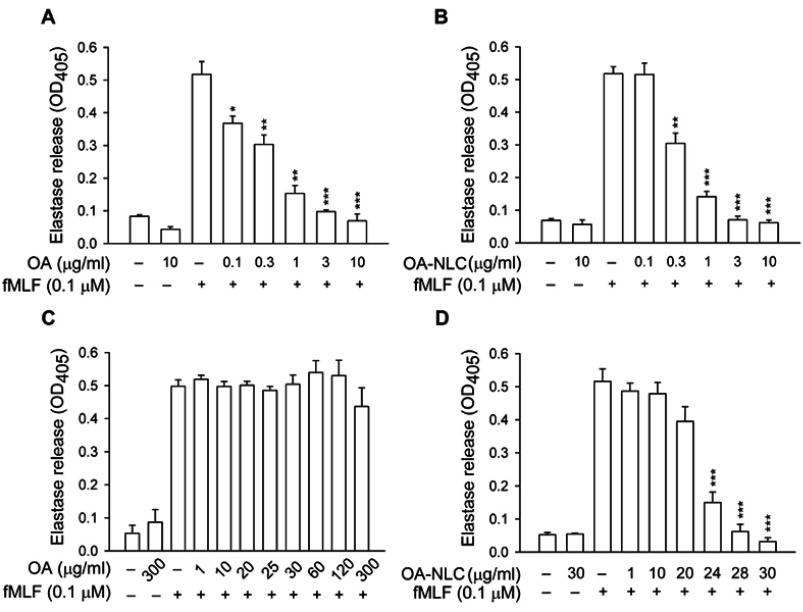

OA-NLC inhibits superoxide generation and elastase release in activated human neutrophils

To determine whether OA-NLC inhibits neutrophil inflammatory responses, we first investigated the effects of OA-NLC on superoxide and elastase release in fMLF-activated human neutrophils. In the absence of BSA, superoxide generation was reduced by both OA and OA-NLC (0.1–10 μg/mL) in a concentration-dependent manner, with IC50 values of 0.72±0.07 μg/mL and 0.83±0.09 μg/mL, respectively. However, in the presence of BSA (0.1%), only OA-NLC presented inhibitory effects on superoxide generation, with an IC50 value of 26.43±0.06 μg/mL (Figure 3). Similar results were observed in elastase release assays. In the absence of BSA, OA and OA-NLC were both shown to inhibit fMLF- or LTB4-induced elastase release (Figures 4 and 5). In fMLF-stimulation experiments, the IC50 values of OA and OA-NLC were 0.23±0.03 μg/mL and 0.42±0.08 μg/mL, respectively. In LTB-4 stimulation experiments, the IC50 values of OA and OA-NLC were 0.91±0.05 μg/mL and 0.61±0.09 μg/mL, respectively. In the presence of BSA, only OA-NLC inhibits the fMLF- or LTB4-induced elastase release, with IC50 value of 22.43±0.78 μg/mL and 23.99±0.82, respectively. Neither OA nor OA-NLC altered basal superoxide generation or elastase release in human neutrophils.

Figure 3.

Effects of OA and OA-NLC on superoxide generation in activated neutrophils.

Notes: Human neutrophils (6×105 cells/mL) were pre-incubated with OA or OA-NLC and then activated with cytochalasin B (1 μg/mL) and fMLF (0.1 μM) in the absence or presence of 0.1% BSA. (A, B) In the absence of BSA, superoxide release was reduced by both OA and OA-NLC. (C, D) In the presence of BSA, only OA-NLC inhibited superoxide release. Superoxide generation was detected spectrophotometrically using ferricytochrome c. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=6, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, as compared to the control assay.

Abbreviations: OA, oleic acid; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers; BSA, bovine serum albumin.

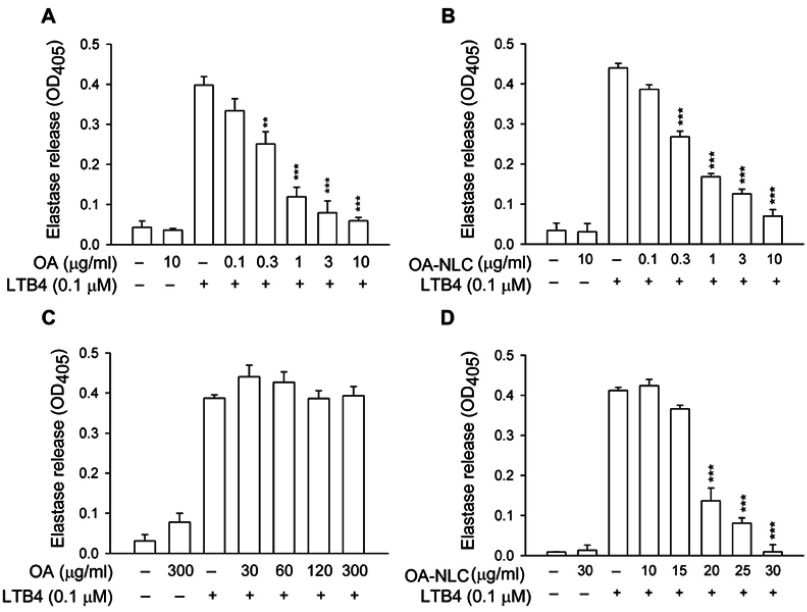

Figure 4.

Effects of OA and OA-NLC on elastase release in fMLF-activated neutrophils.

Notes: Human neutrophils (6×105 cells/mL) were pre-incubated with OA or OA-NLC and then activated with cytochalasin B (0.5 μg/mL) and fMLF (0.1 μM) in the absence or presence of 0.1% BSA. (A, B) In the absence of BSA, elastase release was reduced by both OA and OA-NLC. (C, D) In the presence of BSA, only OA-NLC inhibited elastase release. Elastase release was detected spectrophotometrically using elastase substrate. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=6, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, as compared to the control assay.

Abbreviations: OA, oleic acid; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers; BSA, bovine serum albumin.

Figure 5.

Effects of OA and OA-NLC on elastase release in LTB4-activated neutrophils.

Notes: Human neutrophils (6×105 cells/mL) were pre-incubated with OA or OA-NLC and then activated with cytochalasin B (0.5 μg/mL) and LTB4 (0.1 μM) in the absence or presence of 0.1% BSA. (A, B) In the absence of BSA, elastase release was reduced by both OA and OA-NLC. (C, D) In the presence of BSA, only OA-NLC inhibited elastase release. Elastase release was detected spectrophotometrically using elastase substrate. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=6, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, as compared to the control assay.

Abbreviations: OA, oleic acid; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers; BSA, bovine serum albumin.

Effects of OA-NLC on Ca2+ mobilization

Various neutrophil effector functions, including respiratory burst and degranulation, are regulated by Ca2+ signaling. In the absence of BSA, neither OA nor OA-NLC affected peak [Ca2+]i values in fMLF-activated neutrophils; however, they significantly decreased the time required for [Ca2+]i to return to half of the peak value (t1/2) in a concentration-dependent manner. In the presence of BSA, OA-NLC, but not OA, affected t1/2 values in activated cells (Table 2, Figure 6).

Table 2.

Effects of OA and OA-NLC on Ca2+ mobilization in the absence or presence of albumin

| Without albumin | With albumin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak [Ca2+]i (nM) | t1/2 (sec) | Peak [Ca2+]i (nM) | t1/2 (sec) | |

| Control | 297.34 ± 12.86 | 25.85 ± 2.92 | 346.40 ± 11.43 | 22.84 ± 0.94 |

| OA | 298.17 ± 17.62 | 6.90 ± 0.09*** | 334.62 ± 5.12 | 23.57 ± 0.87 |

| OA-NLC | 325.38 ± 10.05 | 9.40 ± 0.25*** | 371.04 ± 10.68 | 6.53 ± 0.41*** |

Notes: In the absence of albumin, neither OA nor OA-NLC affected peak [Ca2+]i values in activated neutrophils; however, they significantly decreased t1/2. In the presence of albumin, OA-NLC, but not OA, affected t1/2 values. ***P<0.001, as compared to the control assay.

Abbreviations: t1/2, the time required for [Ca2+]i to return to half of the peak value; OA, oleic acid; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers.

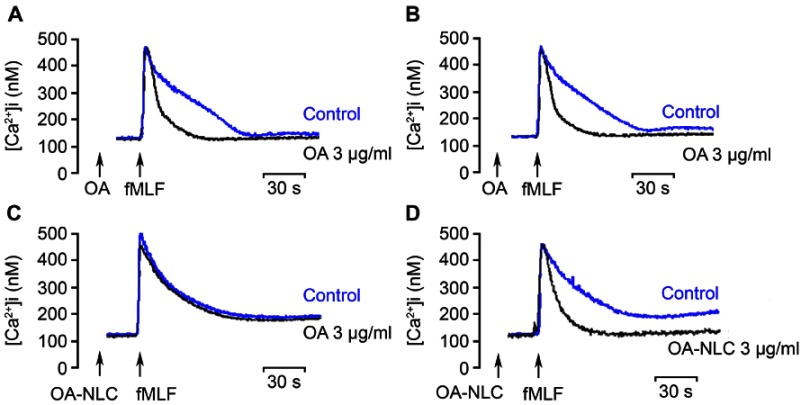

Figure 6.

Effects of OA and OA-NLC on Ca2+ mobilization.

Notes: Fluo 3-loaded neutrophils were incubated with OA or OA-NLC for 5 min. Cells were then activated by fMLF (0.1 μM). Mobilization of Ca2+ was determined in real time in a spectrofluorometer. (A, B) In the absence of BSA, neither OA nor OA-NLC affected peak [Ca2+]i values in fMLF-activated neutrophils; however, they significantly decreased the time required for [Ca2+]i to return to half of the peak value (t1/2). (C, D) In the presence of BSA, OA-NLC, but not OA, affected t1/2 values. Representative traces from four independent experiments are shown.

Abbreviations: OA, oleic acid; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers; BSA, bovine serum albumin.

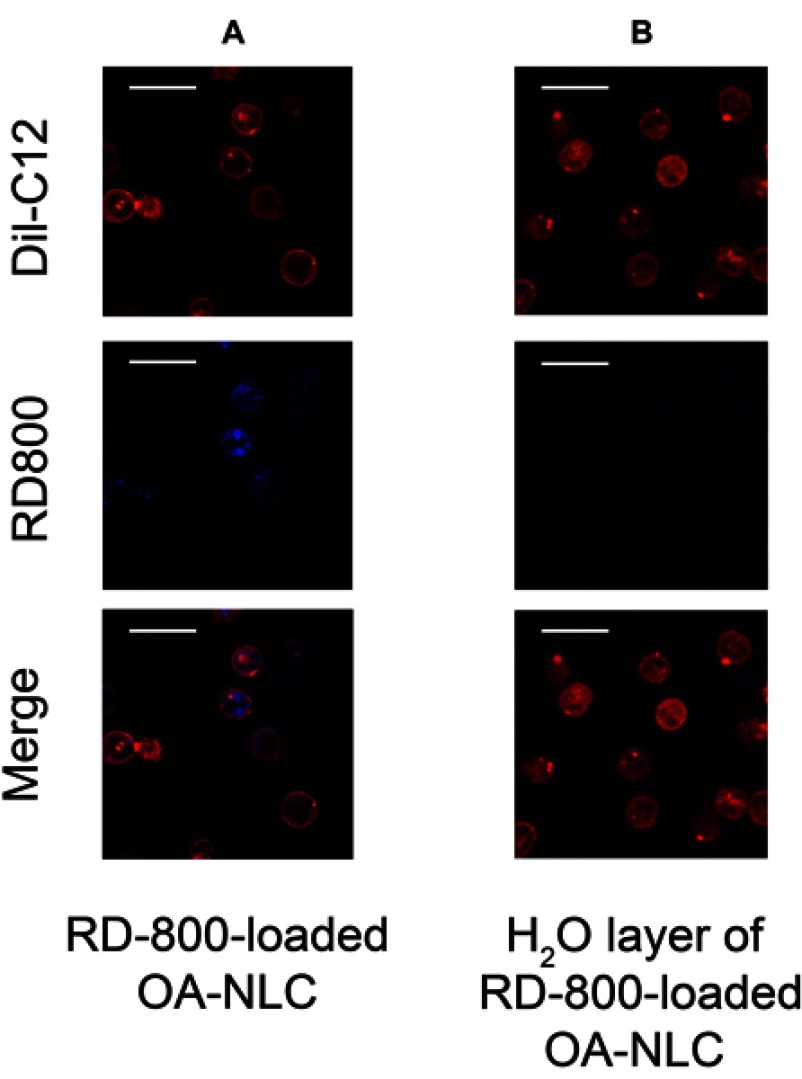

NLC uptake by neutrophils

OA-NLC is known to affect neutrophil activities and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization. We further investigated the interaction between nanoparticles and neutrophils. For this, we visualized the internalization of fluorescence-labeled OA-NLC by neutrophils under CLSM (Figure 7). Five minutes after the coculturing of labeled neutrophils and OA-NLC, notable fluorescence signals were observed throughout the neutrophil cytoplasm. The cell membrane of neutrophils was stained with Dil-C12 and remained intact following the uptake of nanoparticles.

Figure 7.

NLC uptakes by neutrophils.

Notes: Neutrophils (1.8×107 cells/mL were co-incubated with (A) rhodamine 800 labeled-OA-NLC, and (B) H20 layer of rhodamine 800-loaded OA-NLC after configuration, at 37 °C for 5 min. The intracellular fluorescence signal was then observed by CLSM. (A) Fluorescence signals were observed throughout the neutrophil cytoplasm. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Abbreviations: CLSM, confocal laser scanning microscopy; NLC, nanostructured lipid carriers; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers.

Interaction of albumin and NLC

Following the administration of nanoparticles in vivo, a variety of proteins bound to the surfaces of the nanoparticles, which resulted in the formation of distinct nanoparticle-protein complex. We further investigated the physicochemical properties of the produced complex. The average size of albumin-NLC complex was 421.72±0.83 nm following the addition of 5% BSA, which was 200 nm larger than that of pure NLC. Based on these measurements, we estimated that the average thickness of additional corona was estimated to be 200 nm (Figure 8, Table 1). The addition of 5% BSA also changed the zeta potential changes from −40.59 mV to −12.61 mV, indicating that the negative surface charge had been somewhat neutralized. Morphologic observation under TEM revealed that the nanoparticles were surrounded by a protein cloud, which is known as the “protein corona”. The diameter of the complex with a protein corona appeared to be larger than the diameter of the NLC without a protein corona.

Figure 8.

TEM images of NLC interaction with albumin.

Notes: OA-NLC was co-incubated with or without BSA (5%), subsequently applied to a 200-mesh copper grid coated with formvar/carbon film. The sample was then stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid and observed under TEM. The diameter of the NLC-albumin complex with a protein corona (arrow) is larger than that of the NLC without a protein corona (Figure 1).

Abbreviations: NLC, nanostructured lipid carriers; OA-NLC, oleic acid within nanostructured lipid carriers; BSA, bovine serum albumin; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

OA-NLC attenuates the severity of LTB4-induced skin inflammation

An LTB4-induced skin inflammation model was used in our study to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects of topically administered OA-NLC. Inflammation in mouse skin was induced by topical administration of LTB4 (5 μL, 0.5 mg/ear). Skin samples were subjected to HE stain and an assay for MPO activity. We performed skin inflammation assessment on the following groups of mice: sham-operated mice treated with ethanol (5 μL, 10%), mice with LTB4-induced skin inflammation, mice with LTB4-induced skin inflammation pretreated with OA (in ethanol, 5 μL, 0.6 mg/ear), and mice with LTB4-induced skin inflammation pretreated with OA-NLC (in ddH2O, 5 μL, 0.6 mg/ear). As shown in Figure 9, skin inflammation was characterized by epidermal neutrophil infiltration, which was alleviated by both OA-NLC and OA. The significant increase in MPO activity that we observed in inflamed skin is a quantitative indicator of neutrophil infiltration. Administration of topical OA-NLC or OA was found to suppress the increase in MPO activity. OA-NLC showed efficacy superior to that of OA in histology and MPO assay (Figure 9E).

Figure 9.

Effects of OA and OA-NLC on LTB4-induced skin inflammation.

Notes: OA or OA-NLC were applied topically to ear of the mice, followed by the topical application of LTB4 (0.5 μg/mL, in ethanol). Skin inflammation was characterized by epidermal neutrophil infiltration, which was alleviated by OA and OA-NLC. Representative histology images from six independent experiments are shown. Magnification, 400×; inset, 800×, Scale bar represent 50 μm; 25 μm (A) sham-operated mice. (B) Mice with LTB4-induced skin inflammation. (C) Mice with LTB4-induced skin inflammation pretreated with OA. (D) Mice with LTB4-induced skin inflammation pretreated with OA-NLC. (E) Administration of OA and OA-NLC suppress MPO activity, which had a significantly increased in inflamed skin induced with LTB4. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=6, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, as compared to the control assay.

Discussion

Human neutrophils play a critical role in innate immunity by destroying invading pathogens. Neutrophils in the blood stream and at sites of inflammation are in constant contact with fatty acids, which have been shown to have various modulating effects on neutrophils.22 Our findings revealed that OA and other C18 USFAs, including linoleic acid (C18:2, n-6; LA) and α-linolenic acid (C18:3, n-3; αLA), significantly inhibited superoxide anion and elastase release in neutrophils activated with fMLF (Table S1). FAs are transported in the circulatory system in two forms: triacylglycerols or non-esterified FA. Due to the low solubility of non-esterified FAs in aqueous solutions, delivering FAs from adipose cells to FA-consuming cells requires a transporter in both the vascular interstitial compartments. The fact that albumin has various binding sites for FAs,23,24 indicates that FAs can bind to albumin with high affinity.24,25 The cooperative binding of FAs to albumin contributes to FA transport and provides a buffer that maintains the uniform distribution of FAs among various types of tissues.26,27 However, the conjugation of FAs with albumin may interfere the biologic function of FAs, thereby undermining their inhibitory effects on human neutrophil activations. To overcome this, we incorporated OA within NLC to enhance anti-neutrophilic inflammatory effects in the presence of albumin. Furthermore, our in vivo study revealed that OA-NLC can ameliorate the severity of LTB4-induced skin inflammation, which is a clear indication of the transdermal therapeutic effects of OA-NLC.

Table S1.

Effects of unsaturated fatty acids on superoxide generation and elastase release

| Superoxide generation | Elastase release | |

|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μg/ml) | ||

| OA | 0.72±0.07 | 0.32±0.04 |

| LA | 0.84±0.06 | 1.04±0.39 |

| αLA | 1.63±0.22 | 1.61±0.09 |

Notes: OA, C18:1, n-9; LA, C18:2, n-6; αLA, C18:3, n-3. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Abbreviations: IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; OA, oleic acid; LA, linoleic acid; αLA, α-linolenic acid.

We then investigated the mechanisms of which OA-NLC inhibits neutrophil responses. Formylated peptides activate human neutrophils by binding formyl peptide receptor, thereby triggering a number of intracellular effector pathways, such as cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization. A rapid increase in the concentrations of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) was observed within seconds of stimulation by fMLF and sustained for several minutes until returning to normal levels. Intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis is maintained by a variety of mechanisms.28,29 For example, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) is a membrane Ca2+ pump with high-affinity and low-transport, which plays a vital role in preventing Ca2+ overload by exporting Ca2+ from cytosol.30 We previously reported that USFAs inhibits neutrophil activation by activating PMCA, which removes Ca2+ from the cell and thereby decreases Ca2+-modulated cellular activities.12 In this study, we found that neither OA nor OA-NLC affected the rapid release of Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum, as mediated by the PLC/IP3 pathway. However, OA and OA-NLC were both shown to reduce the time required for [Ca2+]i to return to half of the peak value (t1/2). In the presence of albumin, only OA incorporated within NLC, but not free form of OA, reduced t1/2. Our results indicate that reduced neutrophil responses are strongly correlated with the attenuation of Ca2+ mobilization. We therefore posit that the anti-neutrophil effects of OA–NLC are mediated by PMCA-associated Ca2+ mobilization.

The physicochemical characteristics of OA-NLC were also evaluated. The size of NLCs produced in this study ranged from 178 to 276 nm, which is suitable for intravenous administration and percutaneous absorption. The NLCs presented a negatively charged surface resulting from the presence of anionic FAs. The high zeta potentials ( >30 mV) is an indication of good physical stability with little risk of particle aggregation.31,32 TEM results also revealed that the particles are nearly spherical in shape.

Cytotoxicity is a major concern in the development of colloidal nanocarriers.33,34 The biodegradable materials used in the assembly of NLCs in this study have been used in a variety of cosmetic products and pharmaceuticals. We can therefore assume that the NLCs are as safe.35,36 Nevertheless, the nano-scaled size of nanoparticles can potentially promote cellular uptake of themselves, which can result in excessive drug payload or cytotoxicity.32 Nanoparticles have also shown to induce mitochondria-associated oxidative stress, therefore initiating cytochrome P450 enzyme activity and the mitochondrial respiratory chain.34,37–39 Our results show that OA-NLC does not induce superoxide generation or LDH release in human neutrophils. This is a clear indication that the OA-NLC formulations were non-cytotoxic and hence safe for therapeutic application.

Topical therapy is often the mainstay and initial treatment for inflammation-associated dermatologic diseases characterized by neutrophil infiltration. Lipid-based drug delivery systems, such as NLC and SLN, have shown considerable promise in the cutaneous application of active ingredients that are difficult to transport via conventional formulations.16,40 Cutaneous application of NLC forms a monolayer of hydrophobic film, which has an occlusive effect and thus prevents water evaporation. This water contained in stratum corneum reduces intercellular packing of by enlarging the intercellular gaps. Moreover, lipid nanoparticles can also take the follicular penetration route.41 All these promote the permeation and retention of encapsulated molecules in the deeper skin layers.42,43 In this study, we utilized an in vivo animal model of LTB4-induced skin inflammation to evaluate the therapeutic effects of topically administered OA-NLC. Our results demonstrate the efficacy of OA-NLC in reducing neutrophil infiltration and thereby in mediating the severity of inflammation. OA loaded in NLC can provide superior anti-inflammatory effect than that of free OA, indicating that NLC could promote the skin permeation and retention of OA in skin.

Conclusion

This paper reports on the incorporation of OA in anionic NLC to overcome the problem of albumin undermining the anti-neutrophil activities of OA. In the presence of albumin, only OA-NLC (ie, not free OA) was shown to inhibit superoxide generation and elastase release in fMLF-induced neutrophils by regulating Ca2+ mobilization. The ability of topically applied OA-NLC to alleviate the severity of skin inflammation induced by LTB4 is an indication of the potential therapeutic effects of this FA-nano delivery system. Furthermore, our findings indicate that OA and other USFAs incorporated in NLC play a dual role as an active ingredient and a liquid lipid matrix.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgment

This research was financially supported by the grants from the Ministry of Science Technology (MOST 106-2320-B-255-003-MY3, MOST 107-2320-B-182A-008-MY3, and MOST 104-2320-B-255-004-MY3), Ministry of Education (EMRPD1G0231 and EMRPD1H0381), and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPF1F0011~3, CMRPF1F0061~3, CMRPF1G0241~3, and BMRP450), Taiwan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and informed consent

This study was conducted in accordance with a protocol for human subjects that was approved by the institutional review board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. The protocols of animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chang Gung University. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Calder PC. Functional roles of fatty acids and their effects on human health. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39(1 Suppl):18S–32S. doi: 10.1177/0148607115595980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendell SG, Baffi C, Holguin F. Fatty acids, inflammation, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1255–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martins de Lima T, Gorjao R, Hatanaka E, et al. Mechanisms by which fatty acids regulate leucocyte function. Clin Sci. 2007;113(2):65–77. doi: 10.1042/CS20070006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schonfeld P, Wojtczak L. Fatty acids as modulators of the cellular production of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(3):231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez S, Bermudez B, Montserrat-de la Paz S, et al. Membrane composition and dynamics: a target of bioactive virgin olive oil constituents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838(6):1638–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodson L, Fielding BA. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase: rogue or innocent bystander? Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52(1):15–42. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sales-Campos H, Souza PR, Peghini BC, Da Silva JS, Cardoso CR. An overview of the modulatory effects of oleic acid in health and disease. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2013;13(2):201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrillo C, Cavia Mdel M, Alonso-Torre SR. Antitumor effect of oleic acid; mechanisms of action: a review. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1860–1865. doi: 10.3305/nh.2012.27.6.6010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teres S, Barcelo-Coblijn G, Benet M, et al. Oleic acid content is responsible for the reduction in blood pressure induced by olive oil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(37):13811–13816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807500105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva S, Combet E, Figueira ME, Koeck T, Mullen W, Bronze MR. New perspectives on bioactivity of olive oil: evidence from animal models, human interventions and the use of urinary proteomic biomarkers. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74(3):268–281. doi: 10.1017/S0029665115002323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrillo C, Cavia Mdel M, Alonso-Torre S. Role of oleic acid in immune system; mechanism of action; a review. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(4):978–990. doi: 10.3305/nh.2012.27.4.5783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang TL, Su YC, Chang HL, et al. Suppression of superoxide anion and elastase release by C18 unsaturated fatty acids in human neutrophils. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(7):1395–1408. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800574-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan S, Baboota S, Ali J, Khan S, Narang RS, Narang JK. Nanostructured lipid carriers: an emerging platform for improving oral bioavailability of lipophilic drugs. Int J Pharm Investig. 2015;5(4):182–191. doi: 10.4103/2230-973X.167661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraft JC, Freeling JP, Wang Z, Ho RJ. Emerging research and clinical development trends of liposome and lipid nanoparticle drug delivery systems. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103(1):29–52. doi: 10.1002/jps.23773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber S, Zimmer A, Pardeike J. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) for pulmonary application: a review of the state of the art. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014;86(1):7–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garces A, Amaral MH, Sousa Lobo JM, Silva AC. Formulations based on solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) for cutaneous use: A review. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2018;112:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2017.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alalaiwe A, Wang PW, Lu PL, Chen YP, Fang JY, Yang SC. Synergistic Anti-MRSA activity of cationic nanostructured lipid carriers in combination with oxacillin for cutaneous application. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1493. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang JY, Chiu HC, Wu JT, Chiang YR, Hsu SH. Fatty acids in Botryococcus braunii accelerate topical delivery of flurbiprofen into and across skin. Int J Pharm. 2004;276(1–2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CY, Liaw CC, Chen YH, Chang WY, Chung PJ, Hwang TL. A novel immunomodulatory effect of ugonin U in human neutrophils via stimulation of phospholipase C. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;72:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CY, Leu YL, Fang Y, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Perilla frutescens in activated human neutrophils through two independent pathways: Src family kinases and Calcium. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18204. doi: 10.1038/srep18204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Bel M, Brunet A, Gosselin J. Leukotriene B4, an endogenous stimulator of the innate immune response against pathogens. J Innate Immun. 2014;6(2):159–168. doi: 10.1159/000353694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodrigues HG, Takeo Sato F, Curi R, Vinolo MAR. Fatty acids as modulators of neutrophil recruitment, function and survival. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;785:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kragh-Hansen U. Molecular aspects of ligand binding to serum albumin. Pharmacol Rev. 1981;33(1):17–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavicevic ID, Jovanovic VB, Takic MM, Penezic AZ, Acimovic JM, Mandic LM. Fatty acids binding to human serum albumin: changes of reactivity and glycation level of Cysteine-34 free thiol group with methylglyoxal. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;224:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Vusse GJ. Albumin as fatty acid transporter. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24(4):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curry S, Mandelkow H, Brick P, Franks N. Crystal structure of human serum albumin complexed with fatty acid reveals an asymmetric distribution of binding sites. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5(9):827–835. doi: 10.1038/1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cistola DP. Fat sites found! Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5(9):751–753. doi: 10.1038/1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brini M, Cali T, Ottolini D, Carafoli E. Intracellular calcium homeostasis and signaling. Met Ions Life Sci. 2013;12:119–168. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brini M, Carafoli E. Calcium pumps in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(4):1341–1378. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strehler EE. Plasma membrane calcium ATPases: from generic Ca(2+) sump pumps to versatile systems for fine-tuning cellular Ca(2.). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh SK, Srinivasan KK, Gowthamarajan K, Singare DS, Prakash D, Gaikwad NB. Investigation of preparation parameters of nanosuspension by top-down media milling to improve the dissolution of poorly water-soluble glyburide. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;78(3):441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puglia C, Bonina F. Lipid nanoparticles as novel delivery systems for cosmetics and dermal pharmaceuticals. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9(4):429–441. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.666967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doktorovova S, Souto EB, Silva AM. Nanotoxicology applied to solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers - a systematic review of in vitro data. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014;87(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruge F, Damiani E, Marcheggiani F, Offerta A, Puglia C, Tiano L. A comparative study on the possible cytotoxic effects of different nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) compositions in human dermal fibroblasts. Int J Pharm. 2015;495(2):879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehnert W, Mader K. Solid lipid nanoparticles: production, characterization and applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47(2–3):165–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Chen M, Su Z, Sun M, Ping Q. Size-exclusive effect of nanostructured lipid carriers on oral drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2016;511(1):524–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huerta-Garcia E, Perez-Arizti JA, Marquez-Ramirez SG, et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce strong oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in glial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;73:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kulthong K, Maniratanachote R, Kobayashi Y, Fukami T, Yokoi T. Effects of silver nanoparticles on rat hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme activity. Xenobiotica. 2012;42(9):854–862. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2012.670312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Periasamy VS, Athinarayanan J, Al-Hadi AM, Juhaimi FA, Alshatwi AA. Effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles isolated from confectionery products on the metabolic stress pathway in human lung fibroblast cells. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2015;68(3):521–533. doi: 10.1007/s00244-014-0109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sala M, Diab R, Elaissari A, Fessi H. Lipid nanocarriers as skin drug delivery systems: properties, mechanisms of skin interactions and medical applications. Int J Pharm. 2018;535(1–2):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beloqui A, Solinis MA, Rodriguez-Gascon A, Almeida AJ, Preat V. Nanostructured lipid carriers: promising drug delivery systems for future clinics. Nanomedicine. 2016;12(1):143–161. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desai P, Patlolla RR, Singh M. Interaction of nanoparticles and cell-penetrating peptides with skin for transdermal drug delivery. Mol Membr Biol. 2010;27(7):247–259. doi: 10.3109/09687688.2010.522203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhai Y, Zhai G. Advances in lipid-based colloid systems as drug carrier for topic delivery. J Control Release. 2014;193:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]