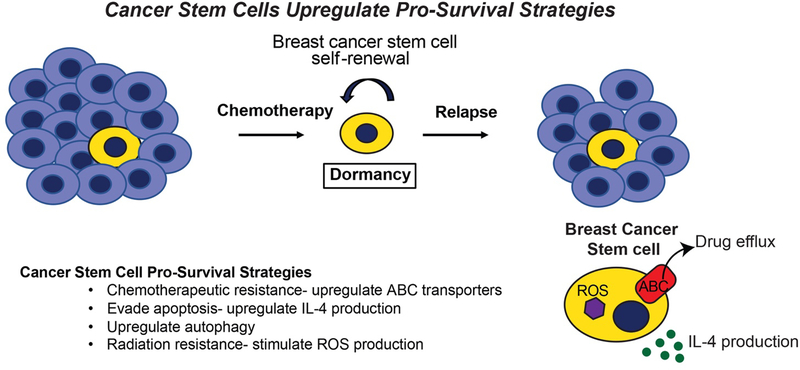

Figure 1. Cancer Stem Cells Upregulate Pro-Survival Strategies.

Early in mammary tumor development, breast cancer cells are shed and disseminated from the growing lesion, ultimately colonizing distant metastatic sites before clinical detection of a primary breast tumor. Upon breast cancer diagnosis, neoadjuvant chemotherapy in conjunction with surgical resection, or more traditionally, surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy are both effective in eliminating the bulk the primary tumor cells. In contrast to bulk tumor cells, breast cancer stem cells manage to survive chemotherapeutic treatment by upregulating a number of pro-survival strategies, thereby contributing to metastatic relapse following a period of remission and dormancy. In doing so, cancer stem cells can (i) upregulate ABC transporter expression, which evades the cytotoxic activities of chemotherapies; (ii) enhance IL-4 production, which inhibits apoptosis; (iii) activate autophagy; and (iv) induce ROS production, which confers resistance to radiation. In addition, breast cancer stem cells also evade apoptosis by lying dormant for years or even decades, a pathophysiological state that further protects these cells from the cytotoxic activities of chemotherapy and radiation, and from the apoptotic activities engendered by metabolic, hypoxic, and environmental stressors.