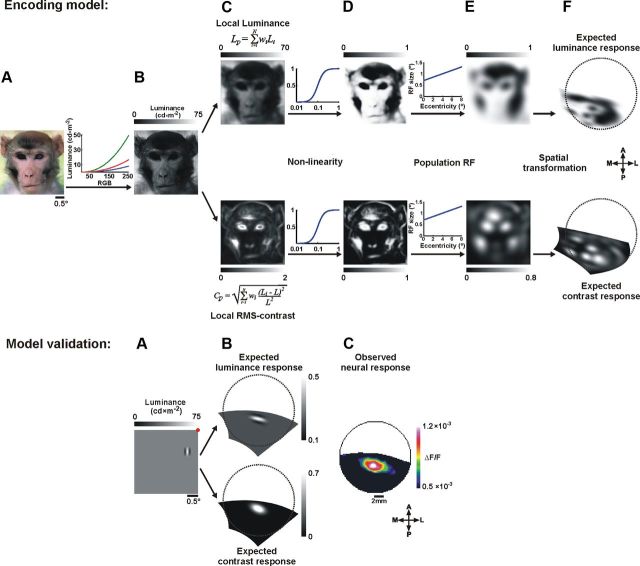

Figure 3.

Computing the expected neural response. Top, A, Example of a visual stimulus. B, The stimulus in A after conversion of each pixel from RGB to luminance values (maximum luminance of the screen = 75 cd × m−2). C, The local luminance (above) and local RMS-contrast (below) obtained by the weighted sum of a circular patch with a radius of 0.15°. D, The stimulus luminance and RMS-contrast shown in C, operated on by a nonlinear function (Naka–Rushton). E, The expected luminance response (above) and the expected contrast response (below) obtained by the weighted sum of a circular population RF (with size that varied linearly as a function of eccentricity). F, The expected luminance and contrast response after spatial transformation to cortical coordinates of V1 (Fig. 2; see Materials and Methods). Bottom, Model validation. Computing the expected neural response of a single Gabor stimulus. A, A Gabor element presented over a gray background. The red dot represents the fixation point of the monkey. B, The expected luminance and contrast response of a single Gabor, after spatial transformation to cortical coordinates (calculated as described above). C, The neural population response evoked in V1 by the presentation of a single Gabor, averaged over two time frames at 60–70 ms poststimulus onset (shown after 2D Gaussian filter with σ = 1.5 pixels). The spatial correlation values between the expected and the observed response are 0.58, 0.83 for the local luminance and local contrast, respectively, calculated over 452 pixels.