Abstract

Objectives

As sexual health information is increasingly presented digitally, and adolescents are increasingly seeking sexual health information on the internet, it is important to explore the challenges presented by this developing source of information provision. This study examined the key barriers and challenges faced by young people when accessing and using sexual health information online.

Methods

A novel qualitative approach was used which combined paired interviews with real-time online activities. A purposive sample of 49 young people aged between 16-19 years and diverse in terms of gender, sexuality, religion and socio-demographic background were recruited from areas across Scotland. Data analysis comprised framework analysis of conversational data (including pair interactions), descriptive analysis of observational data, and data integration.

Results

This study highlighted practical and socio-cultural barriers to engagement with online sexual health content. Key practical barriers included: difficulty filtering overabundant content; limited awareness of specific, relevant, trusted online sources; difficulties in finding locally-relevant information about services; and difficulties in navigating large organisations’ websites. Key socio-cultural barriers included: fear of being observed; wariness about engaging with visual and auditory content; concern about unintentionally accessing sexually explicit content; and reticence to access sexual health information on social networking platforms or through smartphone applications. These practical and socio-cultural barriers restricted access to information and influenced searching practices.

Conclusion

This study provides insights into some of the key barriers faced by young people in accessing and engaging with sexual health information and support online. Reducing such challenges is essential. We highlight the need for sexual health information providers and intervention developers to produce online information that is accurate and accessible; to increase awareness of and promote reliable, accessible sources; and to be sensitive to young people’s concerns about ‘being seen’ accessing sexual health information regarding audio-visual content and platform choice.

Keywords: adolescent, communication technologies, information technology, qualitative research, sexual health

Introduction

Improving sexual health outcomes for adolescents and young people continues to be a top priority in the UK, with transmission rates of new sexually transmitted infections (STIs), teenage pregnancy, and sexual coercion remaining high.1–4 Within this context, it is important for young people to have easy access to good quality information about sexual health issues and services.

Whilst sexual health information can be gathered from a broad range of sources, new digital media (textual, graphical, audio or visual content transmitted over the internet) have altered the information and care delivery landscape. There has been recognition of the potential of digital media to improve access to, provision of, and engagement with sexual health information and care, and internet-based, online sexual health promotion and services have grown both in the UK and abroad.5

Access to the internet is typically viewed as ingrained within young people’s lifestyles, approaching universality for people aged 16-24, predominantly through smartphones.6 Britain’s third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles found that younger people, and those who reported higher sexual risk behaviour, were more likely to have recently used the internet to access information and support for sexual health.7 Young people use the internet to access information about a wide range of sexual health issues, including safe sex, symptoms of STIs, sexual behaviours, and pleasure.8–10 Research has suggested that the anonymity and accessibility of the internet may help users mitigate some of the common barriers to seeking sexual health advice or care in offline contexts, including embarrassment and confidentiality concerns.10–12

With sexual health information increasingly presented digitally, and individuals increasingly seeking sexual health information online, it is important to explore the challenges presented by this developing venue of information provision.13 While young people are typically perceived as ‘digital natives’, fully embedded and competent within the online context14 15, a growing body of literature questions these generalisations as potentially limiting understandings of the challenges young people face.16 However, little research has focused on understanding young people’s experiences of negotiating the demanding and dynamic online environment for sexual health information.9 17 Thus, the aim of this qualitative research study18 was to understand the key challenges faced by young people in Scotland when accessing sexual health information and support online, in order to inform intervention development and better provision of online sexual health information and care.

Methods

Recruitment and sampling

We recruited a heterogeneous sample of young people (aged 16-19 - the age range at which many young people in the UK become, or consider becoming, sexually active) in existing friendship groups (e.g., school friends, childhood friends) to represent diverse perspectives and experiences. Recruitment was facilitated by gatekeepers within youth and community organisations, posters, word of mouth, social media posts, and snowball sampling and all participants were unknown to the interviewer at the time of recruitment. To recruit a purposive sample diverse in socio-economic status and geographical location, participants were recruited from across Scotland from areas that varied by deprivation (using the Scottish Index for Multiple Deprivation) and urban/rural classification (as defined by the Scottish Government, 2014). In total, 49 participants (aged 16-19), diverse in gender, sexuality, religion and geographical location (see Table 1) took part within 25 interviews (23 paired, two individual and one triad). There were not any major differences by different demographic groups in the findings reported here.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| Participant characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 30 | 61 |

| Male | 19 | 39 |

| Age | ||

| 16 | 16 | 33 |

| 17 | 15 | 31 |

| 18 | 9 | 18 |

| 19 | 9 | 18 |

| Sexuality | ||

| Heterosexual | 38 | 78 |

| Gay/lesbian | 5 | 10 |

| Bisexual | 3 | 6 |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 6 |

| Religion | ||

| Roman Catholic | 10 | 20 |

| Other Christian | 2 | 4 |

| None | 37 | 76 |

| Urban/rural | ||

| Large urban area | 20 | 41 |

| Small urban area | 15 | 31 |

| Accessible small town | 8 | 16 |

| Accessible rural area | 6 | 12 |

Data collection

A novel qualitative research design incorporating paired interviews and observational online activities was used to facilitate insights beyond those attainable from self-reported data alone. Research has suggested that participants’ recall of some behaviours, such as online information seeking, may be more accurately reflected in real-time data collection than retrospective reflections,19 and we considered that self-selected friendship pairs would diminish interview and topic discomfort. Participants chose the location of interviews, including: local youth clubs/organisations (n=12); local library or community centres (n=8); private meeting rooms within the University (n=2); and within participants’ homes (n=3).

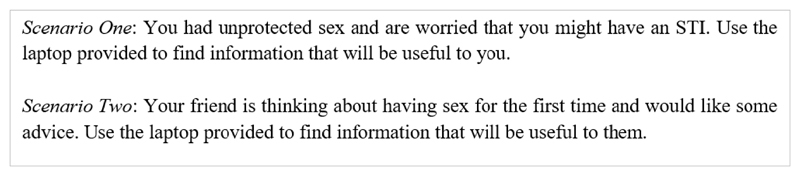

Paired, 90 minutes semi-structured interviews comprised three stages. The first stage explored perceptions and experiences of different sources of sexual health information, including access to, and engagement with, different forms of digital media (conducted by SP, the first author, who was a female PhD student, trained in qualitative research methods, at the time). The second stage comprised a twenty-minute unsupervised online activity, in which participants shared a laptop with a blank web browser to seek information they deemed relevant to two sexual health scenarios (see Figure 1). The scenarios were chosen to encapsulate diverse health information needs with reference to literature on typifying realistic, common situations.19 20 TechSmith Camtasia Studio software was used to capture audio of participants’ conversations and real-time screen captures of their computer use during the online activity. In the third stage, participants provided feedback on the online activity to the interviewer. A pilot study was conducted to test and refine the data collection methods.

Figure 1. Online activity scenarios.

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Glasgow, College of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (application no: 400140170). Participants were provided with detailed information sheets on the purpose and nature of the study and informed consent to record audio and screenshots throughout the interview was obtained. Participants were made aware that they could withdraw consent at any stage.

Data management and analysis

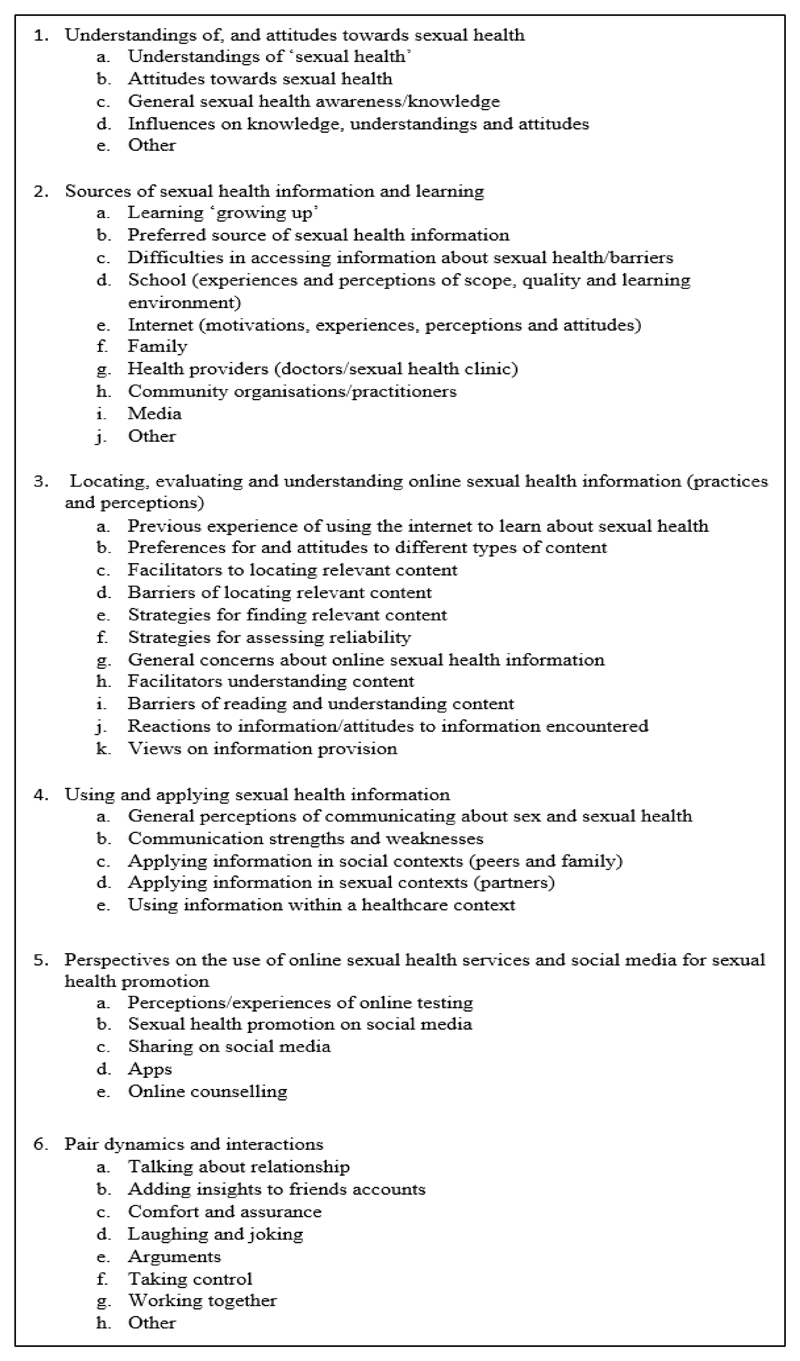

All interview data were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised (using pseudonyms). Transcripts were imported into QSR NVivo 10 software. Data analysis comprised framework analysis of conversational data (including pair interactions), descriptive analysis of observational data, and data integration. Framework analysis was adopted to ensure systematic thematic analysis and facilitate synthesis of key interpretations and themes across the dataset.21 This approach involved five stages: familiarisation (reading and re-reading of interview transcripts and fieldnotes); identification of a thematic framework derived from the data (see Figure 2); indexing (each interview transcript coded systematically and iteratively by theme and sub-theme); charting (creating matrices around each key theme summarising key points, notes and illustrative quotes; see online appendix); and mapping and interpretation (charted data examined to establish typologies, associations and theories around the research questions).

Figure 2. Thematic Framework.

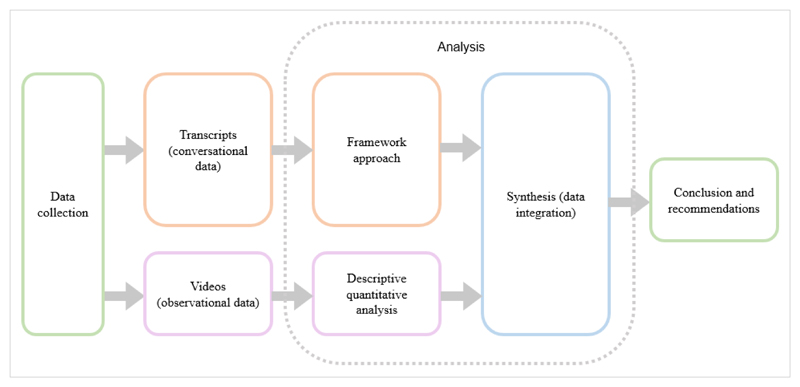

For the online activity, we systematically recorded detailed information about search strategies, websites chosen and the discussions that accompanied these. A coding scheme was developed and methodically applied to the content of the videos to document the pairs’ online information-search processes (see online appendix). Audio-visual recordings of the online activities were analysed thematically to produce descriptive and interpretative summaries of pair’s search processes and the discussions they had during the online activity. The key findings from the interview and online activity were combined in an analytical findings integration table, facilitating synthesis of findings generated across the full paired interview process (Figure 3). All authors contributed to and agreed on the final thematic framework, SP coded the data and prepared matrices, and the coding frame, emergent themes and interpretation of the findings were discussed and agreed within the research team (SP, LMc, SH, PF).

Figure 3. Data analysis and synthesis process.

Findings

Practical barriers to accessing online sexual health information

Participants encountered and identified practical barriers to accessing online sexual health information (Table 2).

Table 2. Additional practical barriers identified by participants.

| Additional practical barriers | Example quote(s) |

|---|---|

| Too much text | I think, like in a way they’ve got lots of information, but for a, a teenager, or even maybe younger, they would get in and be like: “Aw, I’m not looking at that” – and just come back off it. Like if I go onto this one and it’s, this one and there’s like quite a lot of this, and then like, it all just continues the – whole way down the page of different things, I’d get bored with reading that (Mia) |

| Tone of content | We’re talking about adult issues, you know, with our bodies. We’re not here to watch like a Thomas the Tank Engine explain it or anything like that [laughing] (Liam) |

| I think it’s like us, because we’re like teens, we’ll like want to be comforted like we won’t want to be told ‘right, go to your clinic like right away (Jess) | |

| Lack of individually relevant content | There’s a lot of stuff aimed at women…there seems to be a lot aimed at women, know what I mean? There’s no’ really any tips for men (Dylan) |

| Formal and medical terminology | Some of them [websites] were more detailed and more medical words…some people don’t do biology and they don’t know like big long words (Laura) |

| Ones [websites] without slang, what if you don’t know what you’re looking for? Like, words like, ‘cause you might not have heard, like a proper medical name for it. So they’d be like, wouldn’t have like any idea what they’re looking for then (Caleb) |

Many participants mentioned the sheer quantity of content available as a barrier to effectively seeking sexual health information online. For example, Ruth felt that seeking information online could be counterproductive, stating “’Cause you’re gonna get far too many answers on the laptop”. Notably, few participants appeared to know of any specific sexual health websites to visit during the online activity. Exchanges illustrated how a lack of guidance about specific sources could prevent effective online information-seeking:

Claire: Because, like, you don’t really hear about any sites like that. Like, you’d have to look it up yourself and…

Ashleigh: Yeah, it’s never, like, it’s never really…

Claire: You wouldn’t really know where to start

Several participants discussed the value of teenagers being aware of specific sexual health websites. When faced with copious information during the online activity, Courtney said “yeah, I think like most teenagers would look at some of the websites and just be like, ‘no’ and just close it and deal wi’ it themselves”, and her friend Laura replied “but if they knew there was like a specific website that gave them all the information then I think they’d use that”. Some participants suggested that school-based sexual health classes may have a role in referring pupils to relevant and reliable online sources.

Many participants encountered barriers to finding locally-relevant information about sexual health services during the online activity. A common challenge included locating information about local services on large health organisation’s websites containing outdated information and that were difficult to navigate due to unintuitive design. Some participants overcame these barriers with some effort, while others abandoned their searches in frustration at the density of the content:

Abbie: What is this telling me at all? This is not telling me anything.

Sinead: I don’t know…we’re so bad at this

Abbie: We’re not good at this at all.

Additional, less prominent, practical barriers included: too much text, tone of content; obstacles to finding individually relevant content; and barriers to reading and understanding content.

Socio-cultural barriers to accessing online sexual health information

As well as practical barriers, participants illuminated socio-cultural barriers to accessing online sexual health information. Despite many participants’ accounts suggesting that the online environment can alleviate some barriers to seeking information about sexual health encountered in traditional ‘offline’ contexts, worries about ‘being seen’ seeking sexual health information transcended into the online environment and appeared to influence some searching practices.

Images, videos and interactive content seemed to exacerbate participants’ concerns about ‘being seen’ or heard accessing sexual health information online by those in their physical environment. While visual material was typically valued as an engaging and efficient means of communication, it was perceived as potentially undermining attempts to access sexual health information discretely. Charlie explained “It’d make me embarrassed like looking at pictures, like it’d make me worry a wee bit, you know”. Audio-visual content represented an additional means of being observed; Josh highlighted the risk of being heard watching videos, explaining: “Naw [no]! In case my mum and dad heard me”.

Some discomfort with, and avoidance of, audio-visual content appeared to stem from associations with sexually explicit content. For example, Cleo and Alice agreed not to watch an online video in case it was sexually explicit:

Cleo: I think I’d rather just read it. I’d be dead embarrassed. I’m a pure good girl [laughing]

Alice: Yeah. I would be too scared tae like look at the video in case it is gonnae [going to] come up kinda porn-ish

Young women in particular often exhibited risk-averse search strategies to avoid explicit content, such as ‘censoring’ search strings and avoiding image search services and websites containing visual material. During the online activity, Amy expressed concern about the ‘risk’ of explicit content, warning her friend: “Oh no don’t Google it it’s too risky! […] Dinnae [don’t] type in ‘how tae have sex’”.

Despite social networking services (SNS) being a primary focus of participants’ general internet use, most opposed engaging with sexual health promotion content on SNS like Facebook and Twitter. On Facebook, simply ‘Liking’ sexual health content was deemed sufficient to attract judgement, as Josie and Kyle explained:

Kyle: Like you’ve liked it an’ then everybody’s like ‘Oh, why?’

Josie: Like, ‘What’s he dae’in [doing] that for?!’

Kyle: Yeah, ‘What are you dae’in that for, you dirty [a promiscuous person]?!’ [laughing]

Here, Kyle’s use of language highlights the influence of moral attitudes and stigma on sexual health information-seeking. Aaron, who appeared comfortable discussing sexual health, stated that young people would receive “dog’s [harsh] abuse” if seen interacting with sexual health organisations on SNS. Aaron’s friend Michael suggested that the only acceptable interactions “would be sarcastic and jokey”, with irreverence as a protective measure. However, despite this widespread aversion to engaging with sexual health support in the more public areas of SNS, participants were typically positive about the concept of online sexual health support services using private messaging features. An online sexual health messenger service was spontaneously proposed by a number of participants, consisting of online sexual health advisors who could be messaged privately through SNS, such as Facebook, in order to receive advice. Amy raised this as an idea, as she herself was extremely reluctant to interact within formal healthcare contexts and liked that this could offer an alternative setting where her worries could be settled: “'Cause you can worry about a problem for ages and not… be too embarrassed to do anything about it, but if you just do that, like, just gonnae [going to] be a random online just having a quick chat with and then that's it over”. Thus, despite general scepticism across the sample concerning the use of SNS for sexual health promotion, participants were generally keen for support services to be available in more private ways to provide reassuring and personalised advice within a confidential environment.

Participants typically rejected the concept of sexual health apps, despite often describing having fitness and general health apps on their smartphones. Christina and Josh typified this perspective:

What about having a sexual health app?

Christina: No! What if your pals got your phone, they’d be like “what’s this on your phone?”

Josh: Aye I wouldnae…Just go online aye

Christina: Yeah

Josh: ‘Cause you can always, like delete your search history

Josh identified the perceived benefits of discreet, one-off internet searches that can be deleted, in contrast to installing applications that may be seen. Aaron joked that, if he were to see a sexual health application on a peer’s smartphone, he would question “What’s that mad creep doing?”, going on to explain that “You’d get so much abuse”, to which Michael added “That just seems to be the way it is”, perhaps exhibiting awareness of ingrained stigma about engagement with sexual health information and support.

Discussion

This study used a novel approach to explore young people’s real-time experiences of online sexual health information-seeking and highlights practical and socio-cultural barriers that can hinder young people’s engagement with digital media content. Key practical barriers included: overabundant content that can be difficult to filter; limited knowledge of specific, relevant online sources; difficulties in finding locally-relevant information about services; and in navigating large organisations’ dense websites. Important socio-cultural barriers included: wariness about engaging with audio-visual content; concern about unintentionally accessing sexually explicit content; and reticence to access sexual health information on SNS or through smartphone applications.

This paper contributes to the sparse literature focusing specifically on young people’s experiences of accessing online sexual health information. Various studies have established that the online environment can alleviate barriers relating to accessibility and visibility for some young people, compared to accessing sexual health information and care within more traditional ‘offline’ contexts.12 22 However, this study identified some key challenges that should be addressed in harnessing the benefits of the online environment. Research has shown that concerns around embarrassment and shame influence communication about sexual health and access to information within offline contexts.23 24 The evidence presented in this paper suggests that these barriers also exist within the online context, with worries about ‘being seen’ influencing practices. This study responds to a need for research into challenges that may be specific to, or more acute in, seeking sexual health content, in contrast to general health.

The research is subject to certain limitations. While the young people recruited were diverse, some groups were not represented, including those from ethnic minorities and those from remote rural locations. Some were overrepresented, such as young women, with less young men being recruited into the study. Another potential limitation of the sample is that the participants who chose to take part may have been somewhat self-selecting for a willingness to discuss sexual health and having a social support network to draw on. As the study recruited young people in existing friendship pairs, the sample may have underrepresented those who do not have such social support, may struggle the most to communicate about sexual health, and may be more likely to seek support online. Furthermore, dynamics and power relationships within pairs varied, and in some pairs one participant dominated, particularly when their relationship was one of short-term acquaintanceship rather than long-term friendship, possibly underrepresenting the views of the less dominant participant. Conducting some interviews in public settings did raise issues because of noise and privacy, with participants at times distracted by activities elsewhere within the environment, or by others entering the private room and interrupting the interview taking place. Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths, notably the use of an innovative research design integrating interview and observational methods to provoke a range of insights into young people’s perspectives and their practices.

The findings are of relevance to sexual health information and support providers. Participants’ limited awareness of trustworthy online sources of sexual health information might be addressed through targeted promotion of reliable, accessible sources, and, as some participants specifically identified, promotion of such sources in school-based sexual health classes. This suggestion illustrates how schools might make more effective use of the internet, both adding value to information provided in school, and enhancing young people’s own online sexual health information-seeking by recommending specific accessible and authoritative websites. The difficulties experienced by participants in navigating dense websites highlights the need for sexual health information and service providers to produce online information that is accurate and accessible to young people. This is particularly important when they serve as gateways to ‘offline’ services. Furthermore, information providers should be sensitive to young people’s concerns about ‘being seen’, and consider offering content that does not contain eye-catching visual, aural or sexually explicit content that may deter engagement.

This study’s findings also have relevance for intervention development. While the ubiquity of social media in young people’s lives makes this an appealing avenue of health promotion, our findings suggest that concerns about ‘being seen’ are powerful forces that deter young people from engaging with sexual health content on social media.25 As previously suggested, “it is important that health content delivered online does not conflict with the everyday identity work that constitutes a large portion of many young adults’ engagement with social media platforms”.26 Similarly, participants were typically averse to installing sexual health applications where others may observe them. As noted elsewhere, researchers and information providers may view smartphones as inherently personal technologies, while young people perceive them as social devices that are likely to be seen by others.27

However, this is not to say that sexual health promotion on social media services is without merit, particularly given potential advantages over clinician-delivered interventions in terms of time and cost.28 While the interpersonal communication that is a strength of social media29 may not be conducive to sexual health promotion, nuanced understandings of different forms of social media and user-generated content may identify more appropriate settings, such as the relatively anonymous venues of blogs, video-sharing sites and forums. Differences between aspects of larger platforms may also be crucial; while participants would not engage with sexual health information in the semi-public spaces of social media, some identified merit in being able to seek professional advice through private messaging functions of these platforms, which are less vulnerable to ‘being seen’. Barriers of stigma might also be mitigated by certain tones of content, such as the use of humour to encourage the social sharing of sexual health content. 30 As such, realising the potential of sexual health interventions on social media demands nuanced, up-to-date understandings of young people’s perceptions and use of different platforms, aspects of those platforms, and types of content.

Conclusion

Digital media has promise for the improved delivery of sexual health information, but it is necessary that assumptions about young people’s uniform competence as ‘digital natives’ are examined critically so this potential can be realised. This study highlights both practical and socio-cultural challenges that can hinder young people in accessing sexual health information and services online. Potential ways in which stakeholders involved in information provision and intervention development may seek to mitigate those barriers include through: promotion of accessible and authoritative information sources, sensitivity to concerns about audio-visual content, and through private sexual health messaging services. The onus cannot be on young people to increase their individual digital health literacy, rather providers must seek ways to better communicate with young people, promote available services, provide accessible resources and reduce embarrassment and alienation.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

Participants identified a range of practical and socio-cultural barriers to accessing and engaging with sexual health information and support online.

Key barriers included limited awareness of specific sources, difficult-to-navigate websites, concerns over visibility of audio-visual content, and worries about ‘being seen’ engaging with sexual health information on SNS and smartphone applications.

Stakeholders involved in information provision and intervention development could seek to mitigate these barriers through: promotion of accessible sources, sensitivity to concerns about audio-visual content, and use of private sexual health messaging services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of participants who took part in the study and shared their thoughts and experiences.

Funding This study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, through the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow (MC_UU_12017/11, SPHSU 11; MC_UU_12017/2; MC_UU_12017/15, SPHSU15; MC_UU_12017/6). SP was funded by a UK Medical Research Council studentship (1408655).

Footnotes

Competing Interests None.

Patient consent Informed consent was obtained, and participants were made aware that they could withdraw consent at any stage without providing a reason.

Ethics approval Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Glasgow College of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (application no: 400140170).

Contributors SP designed the study, carried out the data collection, coding and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. LMcD, SH and PF contributed to the design of the study, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

"The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in STI and any other BMJPGL products and sub-licences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence http://group.bmj.com/products/journals/instructions-for-authors/licence-forms".

References

- 1.Association for Young People’s Health (AYPH) Young People’s Health, where are we up to? Update 2017. London: AYPH; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Protection Scotland (HPS) Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in Scotland: laboratory diagnoses 2006-2015. [Accessed 6th July 2017];2016 Available at: http://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/documents/ewr/pdf2016/1639.pdf.

- 3.Public Health England. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Chlamydia Screening in England, 2016. Health Protection Report. 2017;11(20) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barter C, Wood M, Aghtaie N, Larkins C, Stanley N, Apostolov G, Shahbazyan L, Pavlou S, Lesta S, De Luca N, Cappello G, et al. Briefing Paper 2, Safeguarding Teenage Intimate Relationships (STIR) DAPHNE III European Commission; 2015. [Accessed 6th July 2017]. Incidence Rates and Impact of Experiencing Interpersonal Violence and Abuse in Young People’s Relationships. Available at: http://stiritup.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/STIR-Briefing-Paper-2-English-final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey J, Mann S, Wayal S, Hunter R, Free C, Abraham C, Murray E. Sexual health promotion for young people delivered via digital: media a scoping review. Public Health Research. 2015;3(13) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ofcom. Adults’ media use and attitudes: Report. London: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aicken C, Estcourt CS, Johnson AM, Sonnenberg P, Wellings K, Mercer CH. Use of the internet for sexual health among sexually experienced persons aged 16 to 44 years: evidence from a nationally representative survey of the British population. Journal of medical Internet research. 2016;18(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borzekowski DL, Rickert VI. Adolescents, the Internet, and health: Issues of access and content. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2001;22(1):49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buhi ER, Daley EM, Fuhrmann HJ, Smith SA. An observational study of how young people search for online sexual health information. Journal of American college health. 2009;58(2):101–111. doi: 10.1080/07448480903221236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barman-Adhikari A, Rice E. Sexual health information seeking online among runaway and homeless youth. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2011;2(2):89–103. doi: 10.5243/jsswr.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couch M, Dowsett GW, Dutertre S, Keys D, Pitts MK. The Australian research centre in sex, health and society monograph series. Melbourne: La Trobe University; 2006. Looking for more: A review of social and contextual factors affecting young people’s sexual health. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon L, Daneback K. Adolescents’ use of the internet for sex education: A thematic and critical review of the literature. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2013;25(4):305–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanton C, Jones KG, Macdowall W, Clifton S, Mitchell KR, Datta J, Lewis R, Field N, Sonnenberg P, Stevens A. Patterns and trends in sources of information about sex among young people in Britain: evidence from three National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. BMJ open. 2015;5(3):e007834. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prensky M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the horizon. 2001;9(5):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helsper EJ, Eynon R. Digital natives: where is the evidence? British educational research journal. 2010;36(3):503–520. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd D. It's Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones RK, Biddlecom AE. Is the internet filling the sexual health information gap for teens? An exploratory study. Journal of health communication. 2011;16(2):112–123. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.535112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin S. Young people's sexual health literacy: seeking, understanding, and evaluating online sexual health information. PhD Thesis; University of Glasgow: 2017. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8528/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen DL, Derry HA, Resnick PJ, Richardson CR. Adolescents searching for health information on the Internet: an observational study. Journal of medical Internet research. 2003;5(4):e25. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5.4.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forrest S, Strange V, Oakley A, The Ripple Study Team What do young people want from sex education? The results of a needs assessment from a peer-led sex education programme. Culture, health & sexuality. 2004;6(4):337–354. doi: 10.1080/13691050310001645050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. The qualitative researcher’s companion. Vol. 2002. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis; 2002. pp. 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barak A, Fisher W. Toward an internet-driven, theoretically-based, innovative approach to sex education. The Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38(4):324–332. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey KJ, Brown B, Crawford P, Macfarlane A, McPherson A. ‘Am I normal?’ Teenagers, sexual health and the internet. Social science & medicine. 2007;65(4):771–781. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMichael C, Gifford S. “It is good to know now… before it’s too late”: Promoting sexual health literacy amongst resettled young people with refugee backgrounds. Sexuality & culture. 2009;13(4):218. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fergie GM. Understanding young adults’ online engagement and health experiences in the age of social media: exploring diabetes and common mental health disorders. PhD Thesis; University of Glasgow: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byron P, Albury K, Evers C. ”It would be weird to have that on Facebook”: young people’s use of social media and the risk of sharing sexual health information. Reproductive Health Matters. 2013;21(41):35–44. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oudshoorn NEJ, Pinch TJ. How users and non-users matter. In: Oudshoorn NEJ, Pinch TJ, editors. How Users Matter. The Co-construction of Technologies and Users. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press; 2003. pp. 4–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ownby RL, Waldrop-Valverde D, Jacobs RJ, Acevedo A, Caballero J. Cost effectiveness of a computer-delivered intervention to improve HIV medication adherence. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2013;13(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruns A. 'Social media: Tools for user-generated content: Social drivers behind growing consumer participation in user-led content generation, Volume 2-User engagement. 2009.

- 30.Evers CW, Albury K, Byron P, Crawford K. Young people, social media, social network sites and sexual health communication in Australia:" This is funny, you should watch it". International Journal of Communication. 2013;7:18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.