Abstract

Objective

Anonymised patient-level data from clinical research are increasingly recognised as a fundamental and valuable resource. It has value beyond the original research project and can help drive scientific research and innovations and improve patient care. To support responsible data sharing, we need to develop systems that work for all stakeholders. The members of the Independent Review Panel (IRP) for the data sharing platform Clinical Study Data Request (CSDR) describe here some summary metrics from the platform and challenge the research community on why the promised demand for data has not been observed.

Summary of data

From 2014 to the end of January 2019, there were a total of 473 research proposals (RPs) submitted to CSDR. Of these, 364 met initial administrative and data availability checks, and the IRP approved 291. Of the 90 research teams that had completed their analyses by January 2018, 41 reported at least one resulting publication to CSDR. Less than half of the studies ever listed on CSDR have been requested.

Conclusion

While acknowledging there are areas for improvement in speed of access and promotion of the platform, the total number of applications for access and the resulting publications have been low and challenge the sustainability of this model. What are the barriers for data contributors and secondary analysis researchers? If this model does not work for all, what needs to be changed? One thing is clear: that data access can realise new and unforeseen contributions to knowledge and improve patient health, but this will not be achieved unless we build sustainable models together that work for all.

Keywords: Data sharing, Clinical trials, Data re-use

Clinical Study Data Request (CSDR) is a consortium of 13 international pharmaceutical companies (GSK, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Chugai, Eisai, Novartis, ONO, Roche, Sanofi, Sunovion, Shionogi Inc, UCB and ViiV) and four academic research funders (The Wellcome Trust, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, The UK Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK).1 It was launched in 2013 and currently lists anonymised patient data from 3374 studies on the platform, including 10 studies from academic funders. The mandate is to reduce the barriers to access and reuse data, thereby facilitating data sharing in an equitable, transparent and independent manner.

Clinical trial data can be used beyond the original purpose for which it was generated, including for analysis of new hypotheses, avoiding duplicative research, ensuring reproducibility and to drive scientific research and innovations to improve patient care. As the value of clinical data is now widely recognised, many global initiatives actively promote and enable sharing of research data and most funders mandate researchers to plan for sharing their data.2–4 The European Medicines Agency and the National Institutes of Health have requirements in place for data disclosure and clinical trial transparency.5 Trial participants’ confidentiality and privacy need to be protected and the terms of consent to participate in research respected. Managed access systems can help with this, including an Independent Review Panel’s (IRP) review of all requests for data access and having data sharing agreements in place that place appropriate restrictions on data usage, though it should be recognised that these systems add time to the process from application to data access.

CSDR’s system allows researchers to request access to anonymised global clinical trial data from multiple studies and sponsors. All data requests that pass initial administrative and data availability checks are reviewed by an IRP, the secretariat for which is provided by Wellcome. Once access is granted, nearly all CSDR members restrict data access to a secure online analysis environment that they say ensures patient privacy while maintaining the utility of the data for secondary analysis. This system can limit the merging of data from other non-CSDR sources and the range of software available for researchers. Free access to data is usually granted for 12 months, with the possibility of extension, and CSDR requires researchers to report on findings, which are then listed on the website.

CSDR metrics

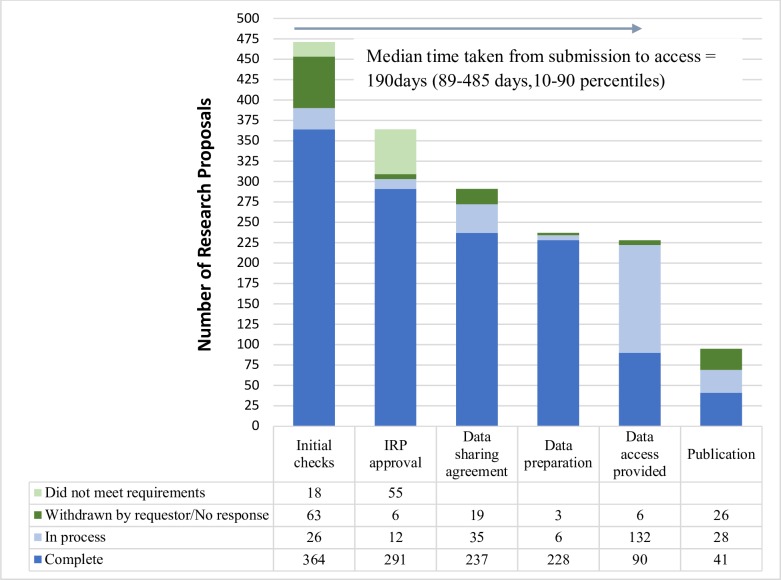

From 2014 to the end of January 2019, there were a total of 471 research proposals (RPs) submitted to CSDR. Of these, 364 met initial administrative and feasibility checks from the sponsors. Although the sponsors have a right to veto a request on the grounds of potential conflict of interest or competitive risk, this veto has never been used. In reviewing applications, the IRP default position is to provide access, and they have approved 291 (84% of those considered) and rejected 55. Thirty-four of the rejected RPs were subsequently revised and resubmitted. The remaining RPs are either still in process, withdrawn or no response has been received from the researchers (figure 1). The most common reasons for rejection were unclear or unsuitable statistical methods (eg, a lack of detail on: the exact meta-analytic method proposed, how models will be validated or how data from different study designs and sites can be combined), too technical lay summaries and insufficient information presented.

Figure 1.

The progress of research proposals through the CSDR system. Of the 471 proposals submitted to CSDR (2014–January 2019), 123 were withdrawn by the requestor at some point through the process. The IRP rejected 55, but 34 of these went on to resubmit revised proposals following IRP suggestions for improvements. Of the 222 that gained access to the data (in progress and completed) 41 have published at least one paper, with another 28 expecting to publish soon. CSDR, Clinical Study Data Request; IRP, Independent Review Panel.

Overall, the annual number of RPs submitted has remained fairly static with 70 submitted in 2014, 96 (2015), 92 (2016), 85 (2017) and 97 (2018). Researchers at institutions in over 30 different countries have submitted RPs, although 168 RPs have been from researchers based in the USA (35%) and very few have been submitted from researchers based in low-income and middle-income countries.

From January 2014, it became possible to request data from multiple sponsors and 17% (73/427) of RPs have requested data from more than one sponsor. However, the median number of studies per RP is 2 (1–5, 25th–75th percentile), with only a handful of RPs requesting a large number of studies (the biggest request involved 192 studies and 11 sponsors).

Of the >4000 studies ever listed on CSDR (over the years, studies have been listed and then removed when sponsors leave the platform), 1457 have been requested. Interestingly, the majority (1157, 79%) have been requested only once or twice, but four have been requested more than 10 times (NCT00153062, NCT00268216 and NCT00410384, which was always requested along with NCT00424476).

Of the 90 research teams that completed their analysis by January 2018, 41 (45%) have at least one publication, 28 (31%) are publishing soon and the remaining 21 have either not published or not responded to reminders from CSDR. Although these numbers appear encouraging in terms of converting access to data into publications of new findings, of concern are the 54 RPs (24%) whose researchers were granted access but did not log into the analysis environment. It is puzzling why this would happen, given the significant investment on both the part of the sponsors and the researchers in getting the RPs to this point in the process. CSDR is planning to contact those researchers to understand their constraints and challenges.

Lessons learned

From an IRP’s perspective, the lessons learnt from the CSDR experience include the following:

CSDR is a valuable resource of data from pharmaceutical companies and academic research funders that is available for free for researchers. However, it is an expensive and resource-intensive task for trial sponsors to provide access to data through this managed access model when it involves secure analysis environments with licenced software, and this may challenge the long-term sustainability of such a platform. With over 50% of studies never being requested, perhaps more resources need to be focused on driving the reuse of data. Research agendas informed by the whole community could drive the sharing and reuse of data for specific questions that are of the highest priority for health practice, although this does limit the resource to current thinking on what is most interesting. The research programmes of the Project Data Sphere cancer data sharing platform is an example of how this model could work.6

Pharmaceutical companies and academic funders should pool resources to strengthen and sustainably support data sharing infrastructure and to develop and implement harmonised principles, standards and best practices.7 The portal cost for the sharing of data should not be prohibitive for new data contributors.

It is important that there is a transparent system in place for data access decisions to maintain equity for all those that want to reuse data. There is a minimum requirement for sufficient statistical skills within the team requesting access to carry out the research proposed, and this may mean there is currently a bias towards higher resourced settings. Funders should consider supporting capacity building efforts to increase the data analysis expertise of teams based in low-income and middle-income settings.

The IRP and the secretariat support provided by Wellcome have been critical to ensuring a trusted and independent managed access system. Having an experienced and multidisciplinary IRP with expertise in ethics, statistics, epidemiology, clinical research and a lay member has helped to ensure that feedback is provided to the data requesters, including suggestions for how to improve proposals with respect to the analysis methods and the clarity of how the research will benefit patients and to ensure all proposals receive consistent review. The IRP’s perspective is to encourage and facilitate data sharing (unless there are significant reasons not to do so). The respected quality of the IRP service has been demonstrated by a newer data sharing platform (Vivli), launched in 2018, requesting the Wellcome IRP also be available for data contributors to their system. The IRP accepted this request and has already considered several proposals through this platform too, applying the same criteria as for CSDR.

It would be helpful if consent for clinical research could, as far as possible, include provision for reuse of their anonymised data beyond the original study.7 In the absence of specific guidance, institutional ethics committees should also adopt consistent policies for the need (or not) for ethics review for secondary use of anonymised data. This would clarify if ethics review is needed (or not), increase the amount of data available for reuse and decrease the time to access the data. Data generators might also feel reassured about using a file transfer model rather than restricting to the use of a controlled analysis environment.

The data access process should be easily discoverable with transparent metrics for potential data users. A common data sharing agreement should be available for all the data providers, and once researchers from an institution have signed the agreement, it should be applicable for other researchers from that institution (to decrease the time often taken by institutions negotiating changes to the agreement).

Merging multiple datasets is critical for finding small or subpopulation effects that could not have been observed from any individual trial alone. However, the resource involved in pooling, or even finding suitable data can be prohibitive if there are no common standards used. CSDR industry sponsors mostly all use Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium standards,8 but the academic research community does not currently employ agreed standards, which is barrier to truly accessible and interoperable data.

The analysis environment must be easily usable by the researchers (including for merging multiple datasets and statistical analysis) and not be expensive for the data providers. Increasing efficiency in the process to ensure that data access happens as soon as possible benefits the researchers (currently, the median time from submission to data access is 190 days in CSDR). It is critical that researchers that get access to the data report their results in a timely manner (eg, within 6 months of completion of data access), so that it helps to move the research field forward and reduce research waste. This should be a requirement in the data sharing agreement.

Some pharmaceutical companies had the fear that data might be accessed for competitive advantage or to disprove trial results. In all the years of CSDR, these fears have been unfounded. This should encourage other pharmaceutical companies to share their data.

Sharing of data on CSDR by academic funders is low and barriers to using the strength of the platform should be identified and addressed. The four academic funders who are CSDR members are currently gathering feedback from their grantees about the challenges and support they need to share clinical data. Other academic funders could encourage their grant holders to start sharing their clinical research data using this or similar platforms.

Conclusions

Sharing of anonymised, patient-level clinical trial data through platforms like CSDR advances research and innovation. International pharmaceutical companies and academic funders are making their data available for free to the research community in a transparent and equitable manner. Challenges still remain to speed up the process and enable data value to be maximised. Researchers need incentives to share, such as citation of their data (which requires unique identifiers to be embedded) being recognised by funders and institutions in decision making. The costs of sharing and reuse need to decrease, which will be helped by adoption of standards in the creation of data, and reduced use of controlled analysis environments. Guidance from professional bodies addressing, for example, consent issues and common data sharing agreements would help promote data sharing. Despite these challenges great advances have already been made, and models developed that mean there are more clinical trial data available for reuse than ever before. We hope this field will continue to develop to meet the needs of all stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the conception, drafting and revision of the article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: GSH is the secretariat for the Independent Review Panel and all other authors are members of the IRP.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Clinical study data request. Available: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Default.aspx [Accessed 20 Jul 2019].

- 2. Institute of Medicine Sharing clinical trial data maximizing benefits, minimizing risk 2015.

- 3. Kiley R, Peatfield T, Hansen J, et al. . Data sharing from clinical trials - a research funder's perspective. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1990–2. 10.1056/NEJMsb1708278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taichman DB, Backus J, Baethge C, et al. . Sharing clinical trial data--a proposal from the international committee of medical journal editors. N Engl J Med 2016;374:384–6. 10.1056/NEJMe1515172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Institute for health sharing policies. Available: https://grants.nih.gov/policy/sharing.htm [Accessed 20 Jul 2019].

- 6. Project data sphere. Available: https://www.projectdatasphere.org/projectdatasphere/html/home [Accessed 20 Jul 2019].

- 7. Burton PR, Banner N, Elliot MJ, et al. . Policies and strategies to facilitate secondary use of research data in the health sciences. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1729–33. 10.1093/ije/dyx195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. CDISC standards in the clinical research process. Available: https://www.cdisc.org/standards [Accessed 20 Jul 19].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.