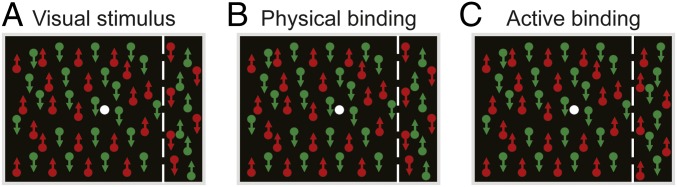

Fig. 1.

Visual stimulus design. (A) The stimulus contains 2 sheets of dots: 1 sheet moving up and the other moving down. On both sheets, dots in the right peripheral area (right of the white dashed line, the effect part) and those in the rest area (left of the white dashed line, the induction part) are rendered with different colors (either red or green). Oppositely moving dots always have different colors. Thus, the induction and effect parts of the stimulus combine color and motion in opposite fashions. For the example stimulus here, on the upward-moving sheet, dots in the induction and effect parts are red and green, respectively. On the downward-moving sheet, dots in the induction and effect parts are green and red, respectively. Intriguingly, when observers fixate at the stimulus center, their perception of the binding of color and motion in the effect part is bistable, switching between the physical binding and the illusory binding. The illusory binding means that the color and motion of the dots in the effect part are erroneously perceived to be bound in the same fashion as those in the induction part. (B) The physical binding state. The color and motion of all of the dots are bound as their physical appearance. (C) The active (illusory) binding state. The illusory binding of color and motion causes observers to perceive upward-moving red dots and downward-moving green dots in the effect part. The illusory binding is actually an active binding process, in which the visual system treats the induction and effect parts as a unitary surface and relies on the information in the central induction part to make inferences about the properties of the peripheral effect part. The white dashed line is for illustration purposes only; it was not shown in the experiments.