Significance

Police violence is a leading cause of death for young men in the United States. Over the life course, about 1 in every 1,000 black men can expect to be killed by police. Risk of being killed by police peaks between the ages of 20 y and 35 y for men and women and for all racial and ethnic groups. Black women and men and American Indian and Alaska Native women and men are significantly more likely than white women and men to be killed by police. Latino men are also more likely to be killed by police than are white men.

Keywords: criminal justice, public health, demography, social inequality

Abstract

We use data on police-involved deaths to estimate how the risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States varies across social groups. We estimate the lifetime and age-specific risks of being killed by police by race and sex. We also provide estimates of the proportion of all deaths accounted for by police use of force. We find that African American men and women, American Indian/Alaska Native men and women, and Latino men face higher lifetime risk of being killed by police than do their white peers. We find that Latina women and Asian/Pacific Islander men and women face lower risk of being killed by police than do their white peers. Risk is highest for black men, who (at current levels of risk) face about a 1 in 1,000 chance of being killed by police over the life course. The average lifetime odds of being killed by police are about 1 in 2,000 for men and about 1 in 33,000 for women. Risk peaks between the ages of 20 y and 35 y for all groups. For young men of color, police use of force is among the leading causes of death.

Violent encounters with the police have profound effects on health, neighborhoods, life chances, and politics (1–9). Policing plays a key role in maintaining structural inequalities between people of color and white people in the United States (1, 10). The killings of Oscar Grant, Michael Brown, Charleena Lyles, Stephon Clark, and Tamir Rice, among many others, and the protests that followed have brought sustained national attention to the racialized character of police violence against civilians (11). Social scientists and public health scholars now widely acknowledge that police contact is a key vector of health inequality (3, 6) and is an important cause of early mortality for people of color (12).

Police in the United States kill far more people than do police in other advanced industrial democracies (13). While a substantial body of evidence shows that people of color, especially African Americans, are at greater risk for experiencing criminal justice contact and police-involved harm than are whites (14–19), we lack basic estimates of the prevalence of police-involved deaths, largely due to the absence of definitive official data. Journalists have stepped into this void and initiated a series of systematic efforts to track police-involved killings. These data enable a richer understanding of the geographic and demographic patterning of police violence (17) and an evaluation of the magnitude of exposure to police violence over the life course.

Prior research has clearly established that race, sex, and age are closely correlated with exposure to the criminal justice system (20–22). Age, race, and gender are also central to the logics that police and legal systems use to decide who to target, how to intervene, and how much force should be applied in the process of policing (5, 23–26).

Research Strategy and Key Findings

This paper provides descriptive estimates of the national prevalence of fatal police violence. In doing so, we contribute to a body of research that uses demographic methods to systematically describe the depth of the involvement of the criminal justice system in the lives of Americans (22, 27–30).

We estimate the risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race, and sex. We also construct period life tables (31) that provide estimates of the risk of death across the life course, with the central assumption that risk profiles observed between 2013 and 2018 remain stable. We use Bayesian simulation and multilevel models to provide uncertainty intervals for our mortality estimates.

Our results show that people of color face a higher likelihood of being killed by police than do white men and women, that risk peaks in young adulthood, and that men of color face a nontrivial lifetime risk of being killed by police.

Focal measures for this analysis rely on data compiled by Fatal Encounters (FE) (32), a journalist-led effort to document deaths involving police. Cases are identified through public records and news coverage, and each variable in the data is validated against published documents. Unofficial media-based methods provide more comprehensive information on police violence than do the limited official data currently available (4, 33, 34).

We focus exclusively on police use-of-force deaths and exclude cases from the analysis that police described as a suicide, that involved a vehicular collision, or that involved an accident such as an overdose or a fall. We provide sensitivity analyses that explore the impact of these inclusion criteria in SI Appendix, Fig. S12. Mortality rate estimates for all groups increase substantially when all recorded cases are included in the analysis.

We describe the data and methods, their limitations, and their assumptions in more detail in Materials and Methods and in SI Appendix.

Results

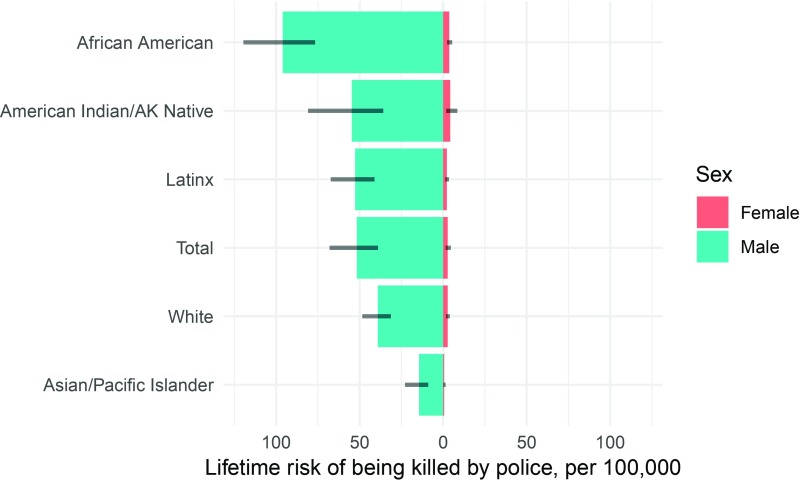

Fig. 1 displays estimates of lifetime risk of being killed by police use of force by race and sex, using data from 2013 to 2018. We estimate that over the life course, at levels of risk similar to those observed between 2013 and 2018, about 52 [39, 68] (90% uncertainty interval) of every 100,000 men and boys in the United States will be killed by police use of force over the life course, and about 3 [1.5, 4.5] of every 100,000 women and girls will be killed by police over the life course.

Fig. 1.

Lifetime risk of being killed by the police in the United States by sex and race–ethnicity for a synthetic cohort of 100,000 at 2013 to 2018 risk levels. Dashes indicate 90% posterior predictive uncertainty intervals. Life tables were calculated using model-based simulations from 2013 to 2018 Fatal Encounters data and 2017 National Vital Statistics System data.

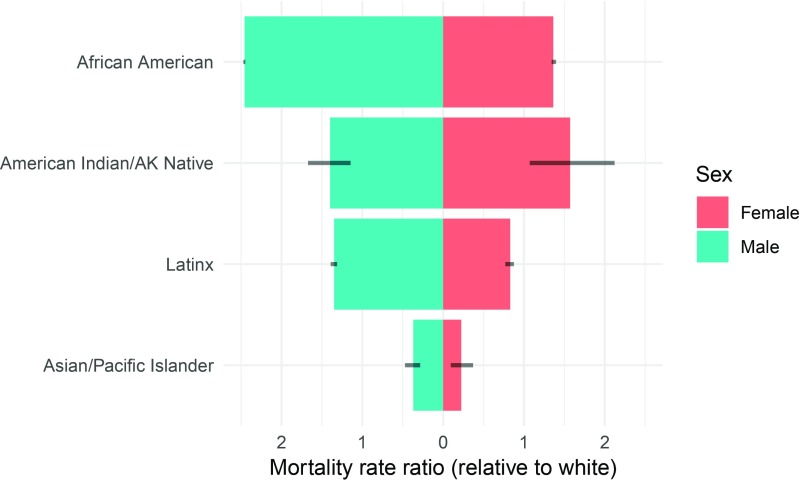

Fig. 2 displays the ratio of lifetime risk for each racial–ethnic group relative to risk for whites for both men and women. Note that a rate ratio of 1 indicates equality in mortality risk relative to whites. The highest levels of inequality in mortality risk are experienced by black men. Black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police over the life course than are white men. Black women are about 1.4 times more likely to be killed by police than are white women. Although risks are estimated with less precision for American Indian/Alaska Native men and women than for other groups, we show that they face a higher lifetime risk of being killed by police than do whites. American Indian men are between 1.2 and 1.7 times more likely to be killed by police than are white men, and American Indian women are between 1.1 and 2.1 times more likely to be killed by police than are white women. Latino men are between 1.3 and 1.4 times more likely to be killed by police than are white men, but Latina women are between 12% and 23% less likely to be killed by police than are white women. Both Asian/Pacific Islander men and women are more than 50% less likely to be killed by police than are white men and women, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Inequality in lifetime risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by sex and race–ethnicity at 2013 to 2018 risk levels. Dashes indicate 90% uncertainty intervals. Life tables were calculated using model simulations from 2013 to 2018 Fatal Encounters data and 2017 National Vital Statistics System data.

Among all groups, black men and boys face the highest lifetime risk of being killed by police. Our models predict that about 1 in 1,000 black men and boys will be killed by police over the life course (96 [77, 120] per 100,000). We predict that between 36 and 81 American Indian/Alaska Native men and boys per 100,000 will be killed by police over the life course. Latino men and boys have an estimated risk of being killed by police of about 53 per 100,000 [41, 67]. Asian/Pacific Islander men and boys face a lifetime risk of between 9 and 23 per 100,000, while white men and boys face a lifetime risk of about 39 [31, 48] per 100,000.

Women’s lifetime risk of being killed by police is about 20 times lower than men’s risk. Among women and girls, black women’s and American Indian/Alaska Native women’s risk is highest; we expect between 2.4 and 5.4 black women and girls to be killed by police over the life course per 100,000 at current rates. American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls are killed by police over the life course at a rate of about 4.2 per 100,000 [1.8, 8.5]. Latina and white women and girls have similar lifetime mortality risks, at about 2 per 100,000. Asian/Pacific Islander women and girls are at the lowest risk of being killed by police for all groups, with a lifetime risk of about 0.6 [0.2, 1.5] per 100,000. However, when other causes of fatality are included in risk estimates, particularly vehicle-related deaths, risk estimates more than double for women across all racial and ethnic groups. We show estimates of lifetime risk at 2013 to 2018 mortality risk levels for multiple causes of police-involved deaths in SI Appendix, Fig. S12.

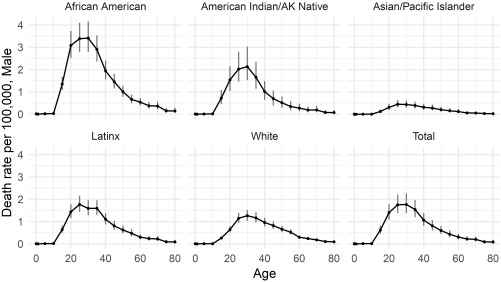

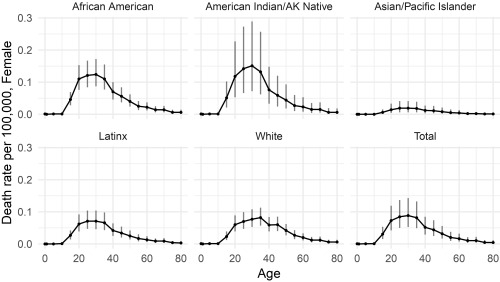

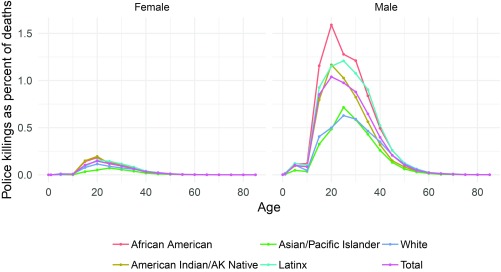

Fig. 3 displays male age-specific rates of death by police use of force by race–ethnicity, and Fig. 4 displays female age-specific rates of being killed by police by race–ethnicity and age. Risk for all groups peaks between the ages of 20 y and 35 y and declines with age. This pattern is similar to the distribution of violent crime (35).

Fig. 3.

Age-specific risk of being killed by the police in the United States by sex and race–ethnicity at 2013 to 2018 risk levels, men and boys. Dashes indicate 90% posterior predictive uncertainty intervals. Life tables were calculated using model simulations from 2013 to 2018 Fatal Encounters data and 2017 National Vital Statistics System data.

Fig. 4.

Age-specific risk of being killed by the police in the United States by sex and race–ethnicity at 2013 to 2018 risk levels, women and girls. Dashes indicate 90% uncertainty intervals. Life tables were calculated using model simulations from 2013 to 2018 Fatal Encounters data and 2017 National Vital Statistics System data.

Between the ages of 25 y and 29 y, black men are killed by police at a rate between 2.8 and 4.1 per 100,000, American Indian and Alaska Native men are killed at a rate between 1.5 and 2.8 per 100,000, Asian/Pacific Islander men are killed by police at a rate between 0.3 and 0.6 per 100,000, Latino men at a rate between 1.4 and 2.2 per 100,000, and white men at a rate between 0.9 and 1.4 per 100,000. Inequalities in risk persist throughout the life course.

We estimate an overall mortality rate of about 1.8 per 100,000 for men between the ages of 25 y and 29 y. This ranks police use of force as one of the leading causes of death for young men. Between these ages, police violence trails accidents (which include drug overdoses, motor vehicle traffic deaths, and other accidental fatalities) at 76.6 deaths per 100,000, suicide (26.7 deaths per 100,000), other homicides (22.0 deaths per 100,000), heart disease (7.0 deaths per 100,000), and cancer (6.3 deaths per 100,000) as a leading cause of death.

Women’s risk of being killed by police use of force is about an order of magnitude lower than men’s risk at all ages, as shown in Fig. 4. Between the ages of 25 y and 29 y, we estimate a median mortality risk of 0.12 per 100,000 for black women, a risk of 0.14 for American Indian/Alaska Native women, a risk of 0.02 for Asian/Pacific Islander women, a risk of 0.07 for Latina women, a risk of 0.07 for white women, and an overall mortality risk of 0.08 per 100,000 for women in this age group. Police use of force is not among the 15 leading causes of death for young women.

Fig. 5 displays the ratio of police use-of-force deaths to all deaths by age, sex, and race. Police use of force accounts for 0.05% of all male deaths in the United States and 0.003% of all female deaths, a low overall share. However, this ratio is strongly correlated with age and race and is starkly unequal across racial groups. Police use of force is responsible for 1.6% of all deaths involving black men between the ages of 20 y and 24 y. At this age range, police are responsible for 1.2% of American Indian/Alaska Native male deaths, 0.5% of Asian/Pacific Islander male deaths, 1.2% of Latino male deaths, and 0.5% of white male deaths. For women between the ages of 20 y and 24 y, police use of force is responsible for 0.2% of all deaths of black women, 0.2% of all deaths of American Indian/Alaska Native women, 0.05% of all deaths of Asian/Pacific Islander women, 0.16% of all deaths of Latina women, and 0.11% of all deaths of white women.

Fig. 5.

Deaths caused by police use of force (median model-based prediction) as a percentage of all deaths by age, race, and sex. Life tables were calculated using model simulations from 2013 to 2018 Fatal Encounters data and 2017 National Vital Statistics System data.

Discussion

Our analysis shows that the risk of being killed by police is jointly patterned by one’s race, gender, and age. Police violence is a leading cause of death for young men, and young men of color face exceptionally high risk of being killed by police. Inequalities in risk are pronounced throughout the life course. This study reinforces calls to treat police violence as a public health issue (1, 4). Racially unequal exposure to the risk of state violence has profound consequences for public health, democracy, and racial stratification (5, 7–9, 11).

Results should be interpreted with several considerations in mind. While the methods used in this paper allow for nationally precise age-, race-, and gender-specific mortality estimates, they may mask important subnational variation and changes in risk over time (17, 36). Because our analysis focuses on some groups that have low age-specific risks, we lack the power to closely consider spatial and temporal trends. However, in SI Appendix, Fig. S3 we show that rates of death have increased by as much as 50% since 2008. Also note that while black people remain disproportionately more likely than white people to be killed by police, the share of white deaths has been increasing in recent years (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Our approach smooths over these changes by treating year effects as random error, but future research should examine these trends closely. Prior research suggests that despite high contemporary rates, the risk of being killed by police was higher in decades past (37).

FE relies on photographs and victim obituaries to classify the race–ethnicity of victims. FE does not currently collect data on variables that may be associated with variation in risk within racial/ethnic groups such as skin tone, multiracial identity, or social class (38). We discuss FE’s methodology and compare FE’s racial data to other sources of data in SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S7. The meaning of race, age, and gender for police violence emerges in the interactions between how officers perceive an individual’s identity and the salience of these classifications for perceptions of criminality, belonging, and dangerousness (1, 10, 25, 39). Future work should closely consider how place, race, gender, age, social class, and disability intersectionally structure exposure to violence (26).

The absence of authoritative official data is a key challenge in reducing police violence. The Bureau of Justice Statistics should renew efforts to develop comprehensive systems to track officer-involved deaths (4, 40). Both the public interest and social science are served by increasing transparency with regard to police use of force. Using such data, the research community has made strides in identifying officers most at risk of being involved in cases of excessive force (41) and system failures that result in civilian deaths (42).

While our research does not evaluate the effects of policy, we believe that several avenues of reform may be fruitful in reducing rates of death. Austerity in social welfare and public health programs has led to police and prisons becoming catch-all responses to social problems (43, 44). Adequately funding community-based services and restricting the use of armed officers as first responders to mental health and other forms of crisis would likely reduce the volume of people killed by police (44). Increasing the ability of the public to engage in the regulation of policing through both investigatory commissions with disciplinary teeth and equal participation in police union contract negotiations would also likely reduce rates of death (45).

Materials and Methods

Our analysis relies on a combination of official and unofficial sources of mortality data: FE and the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) (46). FE collects data on all deaths involving police through systematic searches of online news coverage, public records, and social media. FE provides more comprehensive data on police-involved deaths than do official mortality files (34), has a broader scope than similar unofficial efforts to document deaths, and has been endorsed as a sound source of data by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (47). Despite the relatively high quality of FE, because the data rely on media reports, counts of deaths are likely negatively biased. If any death is not covered by news organizations or is not documented in searchable public records, it will not appear in the data.

Between 2013 and 2018, about 9% of FE cases are missing data on race–ethnicity (SI Appendix, Table S1). We use multiple imputation by chained equations (48) to address missing data for observations between 2013 and 2018. Imputation models include victim age, sex, race, cause of death, and the racial/ethnic composition of the county in which a death occurred. We also include surname-specific estimates of the probability of racial/ethnic group identification on the US Census compiled by Imai and Khanna (49). Results yield similar case compositions to those we observe in NVSS and FE data, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7. Listwise deletion of missing cases unrealistically understates uncertainty in our parameter estimates and negatively biases mortality risk estimates (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

We use these imputed data to construct multilevel Bayesian count models of mortality risk that allow us to directly estimate uncertainty driven by small annual age–race–sex-specific death counts for some groups, by variation in underlying risk over the 6 y of FE data, and by missing data. Intervals reported in the text are drawn from model posterior predictive distributions.

Because we lack sufficient data to track a birth cohort over the life course, we rely on synthetic cohorts to estimate lifetime risk (31). Period life tables allow us to estimate deaths over the life course within a compressed period by tracking age-specific mortality risk over hypothetical cohorts in each subgroup with the key assumption that underlying age-specific mortality risks remain constant at observed levels throughout the life course. All risk estimates presented in this paper can be interpreted as estimates of age-specific or cumulative lifetime risk at 2013 to 2018 police use-of-force mortality rates and 2017 total mortality rates. Our methods are described in more detail in SI Appendix, and an excerpt of our multiple-decrement period life table is displayed in SI Appendix, Table S4.

A replication package containing all scripts and data used in this analysis is available through an Open Science Framework project repository (https://osf.io/c8qxh/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Brian Burghart for collecting and maintaining the Fatal Encounters data. We thank Christopher Wildeman, Peter Rich, Sara Wakefield, Theresa Rocha Beardall, and Robert Apel for advice. Iris Edwards provided valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: All scripts and data used in this analysis are available on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/c8qxh/).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1821204116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Alang S., McAlpine D., McCreedy E., Hardeman R., Police brutality and black health: Setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am. J. Public Health 107, 662–665 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bor J., Venkataramani A. S., Williams D. R., Tsai A. C., Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet 392, 302–310 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller A., Fagan J., Tyler T., Link B. G., Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. Am. J. Public Health 104, 2321–2327 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krieger N., Chen J. T., Waterman P. D., Kiang M. V., Feldman J., Police killings and police deaths are public health data and can be counted. PLoS Med. 12, e1001915 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soss J., Weaver V., Learning from Ferguson: Policing, race, and class in American politics. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 20, 565–591 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sewell A. A., The illness associations of police violence: Differential relationships by ethnoracial composition. Sociol. Forum 32, 975–997 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerman A. E., Weaver V. M., Arresting Citizenship: The Democratic Consequences of American Crime Control (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legewie J., Fagan J., Aggressive policing and the educational performance of minority youth. Am. Sociol. Rev. 84, 220–247 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desmond M., Papachristos A. V., Kirk D. S., Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. Am. Sociol. Rev. 81, 857–876 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhammad K. G., The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor K.-Y., From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Haymarket Books, Chicago, IL, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bui A. L., Coates M. M., Matthay E. C., Years of life lost due to encounters with law enforcement in the USA, 2015 - 2016. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 715–718 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lartey J., By the numbers: US police kill more in days than other countries do in years. The Guardian, 9 June 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/jun/09/the-counted-police-killings-us-vs-other-countries. Accessed 1 January 2018.

- 14.Kramer R., Remster B., Stop, frisk, and assault? Racial disparities in police use of force during investigatory stops. Law Soc. Rev. 52, 960–993 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brame R., Turner M. G., Paternoster R., Bushway S. D., Cumulative prevalence of arrest from ages 8 to 23 in a national sample. Pediatrics 129, 21–27 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettit B., Western B., Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. Am. Sociol. Rev. 69, 151–169 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards F., Esposito M. H., Lee H., Risk of police-involved death by race/ethnicity and place, United States, 2012 - 2018. Am. J. Public Health 108, 1241–1248 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooney A. C., McConville S., Rappaport A. J., Hsia R. Y., Association of legal intervention injuries with race and ethnicity among patients treated in emergency departments in California. JAMA Network Open 1, e182150–e182150 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knox D., Lowe W., Mummolo J., The bias is built in: How administrative records mask racially biased policing. 10.2139/ssrn.3336338 (April 26, 2019). [DOI]

- 20.Gelman A., Fagan J., Kiss A., An analysis of the New York City police department’s “stop-and-frisk” policy in the context of claims of racial bias. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 102, 813–823 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakefield S., Uggen C., Incarceration and stratification. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 36, 387–406 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shannon S. K. S., et al. , The growth, scope, and spatial distribution of people with felony records in the United States, 1948 - 2010. Demography 54, 1795–1818(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward G., Living histories of white supremacist policing. DuBois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 15, 167–184 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rios V. M., Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys (NYU Press, New York, NY, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Legewie J., Schaeffer M., Contested boundaries: Explaining where ethnoracial diversity provokes neighborhood conflict. Am. J. Sociol. 122, 125–161 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie A. J., Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color (Beacon Press, Boston, MA, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pettit B., Invisible Men: Mass Incarceration and the Myth of Black Progress (Russell Sage Foundation, New York, NY, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Western B., Punishment and Inequality in America (Russell Sage Foundation, New York, NY, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakefield S., Wildeman C., Children of the Prison Boom: Mass Incarceration and the Future of American Inequality (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enns P. K., et al. , What percentage of Americans have ever had a family member incarcerated?: Evidence from the family history of incarceration survey (FamHIS). Socius 5, 2378023119829332 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preston S., Heuveline P., Guillot M., Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes (Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, MA, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burghart D. B., Fatal Encounters. https://fatalencounters.org. Accessed 25 January 2019.

- 33.Feldman J. M., Gruskin S., Coull B. A., Krieger N., Quantifying underreporting of law-enforcement-related deaths in United States vital statistics and news-media-based data sources: A capture - recapture analysis. PLoS Med. 14, e1002399 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman J. M., Gruskin S., Coull B. A., Krieger N., Killed by police: Validity of media-based data and misclassification of death certificates in Massachusetts, 2004-2016. Am. J. Public Health 107, 1624–1626 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan R. E, Kena G., Criminal victimization, 2016 (NCJ, 251150, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC, 2017).

- 36.Ross C. T., A multi-level Bayesian analysis of racial bias in police shootings at the county-level in the United States, 2011 - 2014. PLoS One 10, e0141854 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieger N., Kiang M. V., Chen J. T., Waterman P. D., Trends in US deaths due to legal intervention among black and white men, age 15-34 years, by county income level: 1960-2010. Harvard Public Health Rev. 3, 1–5 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monk E. P., The cost of color: Skin color, discrimination, and health among African-Americans. Am. J. Sociol. 121, 396–444 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flores R. D., Schachter A., Who are the “illegals”? The social construction of illegality in the United States. Am. Sociol. Rev. 83, 839–868 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klinger D., Rosenfeld R., Isom D., Deckard M., Race, crime, and the micro-ecology of deadly force. Criminol. Public Policy 15, 193–222 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helsby J., et al. , Early intervention systems: Predicting adverse interactions between police and the public. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 29, 190–209 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherman L. W., Reducing fatal police shootings as system crashes: Research, theory, and practice. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 1, 421–449 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilmore R., Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vitale A. S., The End of Policing (Verso Books, New York, NY, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocha Beardall T. Y., “Transactional policing: Reframing local police-community relations through the lens of police employment,” PhD thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY (2019).

- 46.National Center for Health Statistics , Multiple cause of death data, 2000 - 2017. https://www.nber.org/data/vital-statistics-mortality-data-multiple-cause-of-death.html. Accessed 25 January 2019.

- 47.Banks D., Ruddle P., Kennedy E., Planty M. G., Arrest-Related Deaths Program Redesign Study, 2015-16: Preliminary Findings (Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Buuren S., Groothuis-Oudshoorn K., mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imai K., Khanna K., Improving ecological inference by predicting individual ethnicity from voter registration records. Polit. Anal. 24, 263–272 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.