Abstract

The intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) is disproportionately high in Appalachia, including among adolescents whose intake is more than double the national average and more than four times the recommended daily amount. Unfortunately, there is insufficient evidence for effective strategies targeting SSB behaviors among Appalachian youth in real-world settings, including rural schools. Kids SIPsmartER is a 6-month, school-based, behavior and health literacy program aimed at improving SSB behaviors among middle school students. The program also integrates a two-way short message service (SMS) strategy to engage caregivers in SSB role modeling and supporting home SSB environment changes. Kids SIPsmartER is grounded by the Theory of Planned Behavior and health literacy, media literacy, numeracy, and public health literacy concepts. Guided by the RE-AIM framework (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance), this type 1 hybrid design and cluster randomized controlled trial targets 12 Appalachian middle schools in southwest Virginia. The primary aim evaluates changes in SSB behaviors at 7-months among 7th grade students at schools receiving Kids SIPsmartER, as compared to control schools. Secondary outcomes include other changes in students (e.g., BMI, quality of life, theory-related variables) and caregivers (e.g., SSB behaviors, home SSB environment), and 19-month maintenance of these outcomes. Reach is assessed, along with mixed-methods strategies (e.g., interviews, surveys, observation) to determine how teachers implement Kids SIPsmartER and the potential for institutionalization within schools. This paper discusses the rationale for implementing and evaluating a type 1 hybrid design and multi-level intervention addressing pervasive SSB behaviors in Appalachia.

Keywords: beverages, research design, behavioral research, randomized controlled trial, rural population, health literacy

1. Introduction

The intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB, e.g., soda/pop, sweet tea, sports and energy drinks, fruit drinks) is disproportionately high in Appalachia. Data show that adolescents and adults in the southwest Virginia region of Appalachia drink about 34 ounces (~425 kcals)1 and 38 ounces (~475 calories)2 of SSB per day, respectively. These intakes are more than double national average intakes3 and more than four times the recommended daily amount of less than eight ounces per day.4 Not only is SSB consumption pervasive in Appalachia, it is also the largest single food source of calories in the US diet and contributes approximately 7% of total energy intake for United States adults.5 Appalachia-based data suggest overall added sugar comprises an estimated 21% of total energy intake,6 and similar to national data, SSB is the largest contributor to added sugar intake in the region.

There are also strong and consistent data documenting relationships among high SSB consumption and numerous health issues such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, some types of obesity-related cancers, and dental erosion and decay,7-11 including among youth.7,12-15 Specific to obesity, one recent examination of 13 systematic reviews found that nine concluded a direct association between SSB and obesity in youth.15 Importantly, the four reviews not showing a direct effect were funded by the food and beverage industry or reported a conflict of interest.15

Further compounding the SSB problem in the Appalachian region is a lack of access to medical services and evidence-based prevention programs.16,17 Rural Appalachia is also challenged by transportation issues, geographical isolation, and the digital divide.18-20 Therefore, schools may provide the best opportunity to reach the largest proportion and most representative sample of adolescents. Reaching adolescents with behaviorally-focused health programs at school, where they spend most of their time, shows promise; yet engaging caregivers who are one of their child’s strongest role models and gatekeeper for the home environment is also important.21-26 Furthermore, there is great need to understand how to support schools to implement and maintain evidence-based health education programs,27-29 especially within rural schools.30

While several programs to reduce SSB consumption among youth are evident in the literature, generalizability of findings are limited. In a recent review of 55 studies targeting SSB consumption among youth, it was concluded that existing literature provides insufficient information for real-world settings.30 While the majority of interventions occurred in schools, this review had several notable findings. First, only three trials were conducted in the rural United States, including one in Appalachia. Second, few trials targeted middle school-aged students (16%) and none targeted Appalachian middle-school students. Finally, of the nine school-based interventions targeting middle schools, only one included a parent/caregiver component, and none used technology to engage parents/caregivers.

This current Kids SIPsmartER trial was conceptualized to address these gaps in the literature. Working in partnership with rural Appalachian middle schools, and targeting both middle school students and their caregivers, the overarching goal is to improve SSB behaviors and reduce SSB-related health inequities and chronic conditions in rural Appalachia.

2. Study overview and objectives

Kids SIPsmartER is grounded by the Theory of Planned Behavior as well as health literacy, media literacy, numeracy, and public health literacy concepts. The 6-month, 12 session, school-based, behavioral and health literacy curriculum focuses on improving SSB behaviors among middle school students. The intervention also integrates a two-way short message service (SMS) strategy to engage parents and/or caregivers (hereafter referred to as caregivers) in SSB role modeling and supporting home SSB environment changes. While the digital divide largely pertains to inequalities in accessing computers and the Internet, 95% of US adults own an SMS enabled phone, including 91% of rural US adults.31 Finally, Kids SIPsmartER uses a teacher implementation strategy, including teacher resources, training, and technical support, to deliver Kids SIPsmartER.

Guided by the RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework,32 this type 1 effectiveness-implementation hybrid design and cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) targets 12 Appalachian middle schools in southwest Virginia.33 The RE-AIM framework demands focus on both individual-level (reach, effectiveness and individual-level maintenance) and organizational-level (adoption, implementation, and organizational-level maintenance) processes and outcomes and considers both internal and external validity of study designs and findings.32 Likewise, the type 1 hybrid design guides study decisions and methodologies, with a primary aim focused on intervention effectiveness and secondary aims focused on understanding the context of implementation.33

As such, the primary objective of this trial is to determine the effectiveness of Kids SIPsmartER in changing SSB behaviors among students receiving the intervention, as compared to delayed contact control schools. Secondary outcomes include to: 1) determine changes in other student outcomes (e.g. quality of life, BMI z-score, theory-related variables, health and media literacy), 2) determine changes in caregiver outcomes (e.g., SSB behaviors, home SSB environment), 3) evaluate maintenance of individual-level students and caregivers outcomes at 19-months post-baseline, 4) assess the reach of Kids SIPsmartER among students and caregivers, and 5) explore organization-level factors across schools, including adoption, implementation, and school-level maintenance. Organizational-level factors targeting teachers and principals are explored using a mixed-methods approach including interviews, surveys, and observations.

3. Study region and population

Appalachian communities are disproportionately burdened by numerous nutrition-related chronic diseases, including obesity and cancer.34,35 This burden is compounded by compromised social determinants of health: high poverty rates,36 low educational attainment,37 and limited access to medical care.16,17 This region also has the some of the lowest scores for health behaviors in the state,38 and the majority of the population in the region scores low in terms of health opportunity level.39 Furthermore, the overweight and obesity rate is 65%,40 and middle and high school students have rates of 30 and 28%, respectively.41 Given these disparities and limited access to medical services in the region, prevention efforts must extend beyond traditional healthcare settings.

This study targets middle schools in an 18-county southwest Virginia region of Central Appalachia. Across these 18 counties, 62 middle schools have 7th grade students, of which 26 (42%) meet the school eligibility inclusion criteria and 36 (58%) do not (see Section 5.2; 30 schools have <80 students, four schools have >200 students, two schools do not have 7th and 8th grade in same building). When compared to state averages for Virginia schools, the 26 eligible schools have a higher proportion of White students (48% vs. 93%), students that meet eligibility for free or reduced-price lunches (42% vs. 52%), students classified as economically disadvantaged (40% vs. 55%), and students with chronic absenteeism (11% vs. 17%).42 The average 2017-2018 Standards of Learning (SOL) pass rate among these 26 schools averaged 81% (range 66% to 92%), which is nearly identical to state average pass rate (80%).42

4. Theoretical and conceptual framework

Kids SIPsmartER is a multi-level intervention that uses both individual- and micro-level strategies to target students and their caregivers (Figure 1). With a primary outcome focused on student’s SSB behavior, Kids SIPsmartER integrates the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), with interrelated skill-based health literacy concepts (e.g., numeracy, media literacy and public health literacy). The TPB is one of the most well-studied and valuable theories for understanding health behaviors and has been applied to a wide variety of health contexts, including dietary behaviors43-47 and SSB research.48-50 Numerous systematic reviews have summarized the usefulness of the TPB to predict intentions and behaviors,51-53 including among youth.54 While the TPB is extremely helpful in conceptualizing targeted messages, behavioral strategies and evaluation procedures; targeting skill-based health literacy factors are also important to achieve improvements in SSB behaviors.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for Kids SIPsmartER

Kids SIPsmartER also applies health literacy design features and strategies. First, key design features include simple, clear, and culturally-sensitive messaging with repetition; visual and experiential learning techniques; action planning and monitoring; and application of clear communication strategies for written materials.55,56 Second, there is a focus on numeracy,57 due to the numeric demands involved with applying information on the nutrition facts panel of SSBs58 and the low use of nutrition labels among lower socioeconomic groups.59,60 Third, in an effort to mitigate any negative individual health consequences from overexposure to SSB media, Kids SIPsmartER incorporates media literacy concepts that foster skepticism toward advertising and develop critical thinking skills necessary for identifying health (mis)claims in SSB advertising.61,62 Kids SIPsmartER builds off other media-literacy literature in adolescents63-67 and SSB-specific media literary research.68,69 Finally, Kids SIPsmartER uses public health literacy concepts to show students regional disparities in SSB behaviors and health-related outcomes and help them understand these differences do not have to exist.70 As such, Kids SIPsmartER focuses on conceptual foundations, critical skills, and orientation to civic responsibility.

At the micro-level, Kids SIPsmartER also targets caregivers by focusing on role modeling and the home environment as well as caregivers’ SSB behaviors. Established ecological models highlight the important role of caregivers in child health and obesity.71,72 Specific to SSB behaviors, research has established the role of caregivers and the home environment.21-26 Consequently, Kids SIPsmartER is guided by the premise that caregivers influence their child’s SSB attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intentions and ultimately SSB behaviors through role modeling, SSB practices and rules, and controlling the availability and accessibility of SSBs in the home. These key micro-level influences are targeted via the integrated two-way SMS caregiver component of Kids SIPsmartER.

Though intervening on macro-level SSB factors are beyond the scope of this study, these influences are indirect targets of the Kids SIPsmartER curriculum. For example, the curriculum is designed to help students understand and appreciate the ways SSBs affect their community and society-at-large. Likewise, the intent is to help motivate the students to address SSB-related disparities by advocating and creating macro-level changes (e.g. social, environmental, policy) in their own rural, Appalachia schools and larger communities.

5. Study design and procedures

5.1. Study design, timeline, and randomization

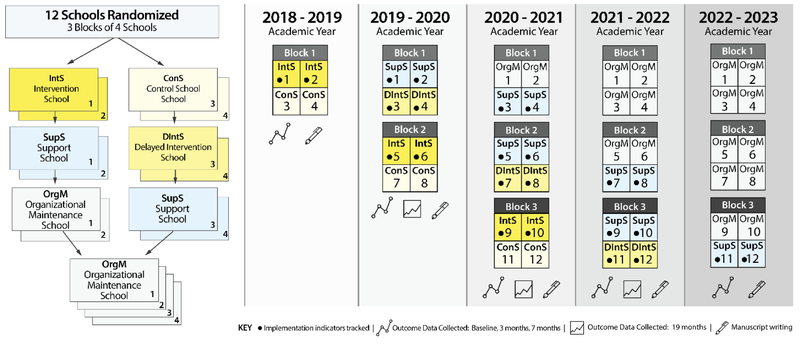

The study design, timeline, and randomization scheme are illustrated in Figure 2. The study was designed with input from school informants and with a key intent to allow schools equal opportunity to benefit, regardless of randomized treatment allocation. Also, due to reported turnover in administration/teachers and fluctuations in resources, it was unrealistic to request a school to enter into a research agreement for a project that is potentially three to four years away. Therefore, to promote sound randomization and school retention, four schools are recruited each year and randomized within three separate blocks (i.e., 12 schools total). The superintendent and principal of each school serve as the ‘cluster guardian’ and must agree to participation and for their school to be randomized.73 Subsequently, pure randomization is used within each block, with two schools randomized into the Intervention School condition and two into the Control School condition. In the Control School condition, the 7th grade students and their caregivers are invited to participate in the data assessments, but do not receive the intervention. Schools randomized into Control School conditions transition into the Delayed Intervention School in the following academic year, while the Intervention Schools transition into Support Schools.

Figure 2.

Kids SIPsmartER study design, timeline, and block randomization scheme

In each school’s first year of implementation (either as an Intervention School or Delayed Intervention Schools), Kids SIPsmartER is co-delivered by researchers and teachers. In the school’s second year of implementation, the Support School year, teachers are trained and receive technical assistance to lead the delivery of Kids SIPsmartER, with reduced in-class support from researchers. Schools have the option of sustaining Kids SIPsmartER into Organizational Maintenance School years and continue to receive training and technical assistance. To assist in implementation, teachers have access to a secure website that contains all student curriculum and teacher training resources.

Student and caregiver individual-level data is collected during Intervention School, Delayed Intervention, Control School, and Support School years, but not during Organizational Maintenance years. Individual-level maintenance data is collected as students’ matriculate into 8th grade. School-level, implementation indicators are tracked in Intervention School, Delayed Intervention, and Support School years, but not during Organizational Maintenance years.

All study procedures have been approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board. After verbal consent is obtained from the superintendent and principal and subsequent randomization, parent consent and student assent are obtained. Since the Kids SIPsmartER curriculum activities and evaluation are a part of a normal classroom period, all students can participate, regardless of consent or assent status. However, only data from consented and assented students are used for research purposes. Due to the cluster-randomized design and in attempts to prevent or reduce selection bias, there are two sets of consent forms (i.e., participants are blinded to the cluster design and study hypotheses).73 One details the procedures for Kids SIPsmartER intervention conditions and the other details procedures for the control condition. On both consent forms, caregivers select one of three options: 1) their student only to participate in the research, 2) their student and themselves to participate in the research, or 3) neither to participate in the research. Through an assent process, students also indicate if their data may be used for research processes. In collaboration with school administrators and teachers from Block 1, these study procedures were designed to comply with human subjects’ protection principles, while minimizing classroom disruptions and selection bias within each cluster.73

5.2. Schools & teachers: Eligibility criteria, recruitment, incentives, and compensation structure

School eligibility criteria include location in the geographical Central Appalachia catchment area in southwest Virginia, with approximately 80 to 200 students in the 7th grade, and an 8th grade within the same school building as 7th grade. The latter eligibility criterion is in an effort to promote student retention at the 19-month data point. Superintendents and middle school principals are fully informed of the study design and protocol and must agree to the randomization procedures. Likewise, they must agree to nominate and approve teachers to help facilitate the logistics of implementing the curriculum and data collection components. Schools have flexibility on which course/subject (e.g., health/physical education, science) Kids SIPsmartER is integrated into their school.

Each participating school receives a $1500 incentive during the first and second years of Kids SIPsmartER implementation for a total incentive of $3000/school. Additionally, the six schools identified as control schools receive $1000 in incentives for participating in data collection. Finally, $1000 is offered for those schools who choose to maintain Kids SIPsmartER programming for an additional year.

Teachers who are nominated by their principal and agree to facilitate the implementation of Kids SIPsmartER have tasks that occur both within and outside of the normal school day. Examples of tasks within the normal school day include distributing and collecting consent forms, delivering the Kids SIPsmartER curriculum, and coordinating data collection. Examples of tasks that occur outside of their normal school day include professional development meetings and trainings, technical assistance related to classroom preparation, school-level process evaluation activities, and communicating with the research team. For tasks that occur outside of the normal school, teachers are hired as external research consultants and are compensated at a rate of $25/hour. Though teachers’ involvement may vary greatly within and among schools, it is projected that each teacher consultant would contribute about 53 hours of time outside the normal school day over the duration of the Kids SIPsmartER trial.

5.3. Students & caregivers: Eligibility criteria, recruitment, consent/assent, and incentives

Within each school, all 7th grade students are eligible to participate. However, data are excluded for students with major cognitive disabilities and for students who are not regular attendees in the Kids SIPsmartER curriculum (e.g. learning, behavioral, or discipline reasons). Information provided by the schools is used to make these exclusion decisions. One caregiver per 7th grade student is eligible to participate. Willingness to receive and respond to text messages throughout the Kids SIPsmartER intervention is described in the consent document (and cell phone and contact information are provided). However, all caregivers who complete and return the baseline survey are enrolled in the study, regardless of functioning cell phone status.

Recruitment efforts for caregivers and students are customized to the needs of each school and based on a combination of strategies that have shown to increase response rates.74,75 At each school an informational letter signed by the school’s principal, a study flyer, and a consent form are sent home with students to give to their caregivers. Teachers assist with distributing student and caregiver consent forms, collecting forms, and following-up with students who have not returned consent forms. Additional strategies at some schools include the use of robo-calls to inform families about Kids SIPsmartER, members of the research team attend “Back-to-School Nights” and/or PTA meetings to inform caregivers about Kids SIPsmartER, and a personalized phone call to caregivers to remind them to return the consent forms and to answer questions about the study.

The student assent procedure is conducted in conjunction with in-class data collection procedures. An assent statement is read and reviewed with students, and all questions are answered. Students sign the assent form and indicated if they agree for their data to be used for research purposes (though data is only used if caregivers also provide consent). Students who return the signed consent form (permission granted or denied) receive a nominal prize (e.g. highlighter, bag, water bottle). At the 7-month assessment, students receive a Kids SIPsmartER t-shirt. Caregivers receive a $10 gift card each time they return a survey, including at baseline, 7-month, and 19-months ($30 total).

6. Preliminary research: History of intervention development and progression

Prior to the Kids SIPsmartER study, the research team had an established Appalachia-based SSB research agenda that focused on adults and resulted in the establishment of SIPsmartER, an evidence-based intervention to improve SSB behaviors. The underlying theoretical framework of SIPsmartER, including the Theory of Planned Behavior and health literacy concepts, was originally established through an initial series of formative research projects49,50,76 and subsequently, a full-scale RCT of SIPsmartER followed by pilot dissemination and implementation trial. Then, a second series of pilot projects were executed to adapt the adult-focused SIPsmartER intervention, to Kids SIPsmartER, a multi-level school-based intervention targeting middle school students and their caregivers. The following sections summarize these studies.

6.1. SIPsmartER: Effectiveness and Feasibility

An effectiveness trial for SIPsmartER was executed among 301 Appalachian adults.33 SIPsmartER is a 6-month behavioral and health literacy intervention comprised of 1) three small group classes that covered key behavioral content and action planning, 2) one live teach-back call that provided an opportunity for participants to teach back key concepts from the first class and verify understanding of the behavioral diary tracking process,77 and 3) 11 interactive voice response calls that engaged participants in reporting SSB intake and personal action planning, including identification of barriers and strategies, as well as provided brief theory-based reinforcement messages. SIPsmartER improved 6-month SSB behaviors78 and sustained improvements during a 12-month maintenance phase.79 Furthermore, SIPsmartER participants improved overall dietary and beverage quality,6,80 demonstrated improvement in a δ13C added sugar intake biomarker,81 and achieved small, yet significant, improvements in weight and BMI.78 Quality of life and numerous theoretical targets also improved among SIPsmartER participants.48,78

Given the successes of this effectiveness trial and evidence for SIPsmartER, this RCT was followed by a pilot dissemination and implementation trial in partnership with four rural Southwest Virginia Department of Health (VDH) districts. Through the collaborative development and execution of a SIPsmartER consultation-based implementation strategy, this mixed-methods and pre-post study explored how rural, medically-underserved public health districts adopt and implement SIPsmartER.82 In-person classes and the implementation strategy were viewed as acceptable, appropriate, and feasible and were executed with fidelity. However, implementation outcomes for teach-back and missed class calls and recruitment were not as strong. When compared to the previous RCT effectiveness trial, existing VDH staff achieved stronger effects for improvement in SSB behaviors. For reach and other secondary effectiveness variables, results were comparable to the RCT for most, but not all, outcomes.83 Resources developed and lessons learned through the VDH pilot implementation trial, were adapted and applied to develop the teacher implementation strategy for Kids SIPsmartER.

6.2. Kids SIPsmartER, Youth participatory curriculum development and feasibility testing

Adapted from the adult based SIPsmartER intervention, Kids SIPsmartER is also grounded by the Theory of Planned Behavior as well as health literacy, numeracy, media literacy, and public health literacy concepts.43,55-57,62,70 In 2015, middle school students from one Appalachia county took part in a youth-participatory research process that included a three-day summer camp. During this process, students received six Kids SIPsmartER lessons, completed key learning activities, and provided qualitative and quantitative evaluation data. The purpose of this formative process was to understand the age and cultural appropriateness of the adaptations and confirm targeted theoretical constructs were addressed. This process revealed numerous opportunities to better address theoretical targets and to enhance cultural acceptability of the Kids SIPsmartER program.84

Following the summer camp and additional curriculum revisions guided by the students’ feedback, a feasibility study of Kids SIPsmartER was conducted in one Appalachia middle school in 2015-2016. This matched-contact randomized crossover study used a mixed-methods approach and focused on limited effectiveness, demand, acceptability, implementation, and integration.1,85 In this feasibility study, Kids SIPsmartER consisted of six weekly classroom lessons and also included five 60-second caregiver phone calls delivered through the school’s one call system. The intervention was delivered by trained research assistants. Two teachers assisted and responded to feasibility outcomes through standardized forms and interviews. Results revealed significant improvements in SSB behaviors, media literacy and public health literacy among middle school students receiving Kids SIPsmartER.1 Also, students and teachers found Kids SIPsmartER acceptable, in-demand, practical, and implementable within existing school resources. Due to limitations of the one call system, the proportion of caregivers who received a call was not tracked and data were not collected from caregivers. Overall, it was concluded that Kids SIPsmartER was feasible in an under-resourced, rural school setting. However, the teachers and principal emphasized the need to strengthen future caregiver engagement efforts.

6.3. Caregiver focus groups and SMS pilot for Kids SIPsmartER

SMS, a basic mobile phone feature that does not require a smartphone, was chosen as an intervention modality to engage middle school caregivers based on prior SMS literature,86-89 regional data indicating that approximately 76-82% adults use SMS in the targeted southwest Virginia counties of rural Appalachia, and advice from regional school informants. SMS messages are limited to 160 characters and are an ideal platform from which to directly send short communications to individuals in rural Appalachia. The intent of the Kids SIPsmartER SMS strategy component for caregivers is two-fold: 1) to improve the parenting practices, role modeling, and the home environment to support improvements in student SSB behaviors, and 2) to address barriers and provide strategies to improve caregiver SSB behaviors. To initiate development of the SMS message bank and programming logic, content from the interactive voice response system used in the adult trial was modified.48,78 Then, a mixed-methods elicitation process was conducted to help further refine and tailor the SMS strategy for caregivers.

The primary purpose of the formative research targeting caregivers of middle school students was to understand content preference (e.g., tone of voice, liked/disliked words), audience perceptions, and acceptability of text messages. The secondary purpose was to understand the actual use of text messaging and explore the impact of a brief, five-week text messaging intervention on SSB behaviors. Five focus groups, including caregivers of middle school students, were held across southwest Virginia and was followed by a five-week SMS pilot trial. During the focus groups, tone of voice preferences emerged, as well as liked and disliked words and phrases. After completing the SMS pilot trial, caregivers reported the SMS components were highly acceptable and beneficial. Preliminary analyses of SMS based assessments from the brief SMS pilot trial revealed that both caregivers and children significantly reduced SSB intake and caregivers reported significant improvements in the SSB home environment and SSB parenting practices. Results from this formative study were used to further develop and refine the SMS strategy and programming logic for the larger Kids SIPsmartER trial, including SSB behavioral assessments, feedback loops, and message bank (further described below).

7. Kids SIPsmartER intervention

Data and lessons learned from the summer camp, school feasibility testing, caregiver focus groups, and pilot SMS trial were assimilated and used to further refine and finalize Kids SIPsmartER. As illustrated in Figure 3, for the full-scale effectiveness trial, Kids SIPsmartER is a 12 lesson, 6-month program for students with an integrated two-way SMS strategy to engage caregivers. Kids SIPsmartER also includes a teacher implementation strategy that consists of professional development and technical assistance.

Figure 3.

Summary of Kids SIPsmartER, a multi- level intervention to improve sugar-sweetened beverages behaviors among Appalachia students and their caregivers

7.1. Student curriculum

Each of the 12 classroom based lessons are designed to fit with one 40-50 minute class period (Figure 3). The first nine lessons are delivered weekly in the fall semester; the remaining three lessons are delivered monthly in the spring semester. In general, lessons 1-6 focus on making personal changes, lessons 7-9 emphasize encouraging change in their community, and lessons 10-12 focus on motivating and maintaining changes. Table 1 provides an overview of lesson titles, learning objectives, primary behavioral change techniques,90 and targeted theoretical constructs. Using a drink traffic light system (red light, yellow light, green light), students are educated on six main categories of sugary drinks (soda/pop, fruit-flavored drinks, energy drinks, sweetened milk drinks, sweetened coffees and teas, sports drinks) as well as non-sugary drinks (water, milk, unsweetened coffee and tea, diet drinks).

Table 1.

Intervention overview of Kids SIPsmartER: structure, theoretical constructs and content.

| Lessons delivered in classroom |

Caregiver SMS messages |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesson: lesson title | Learning objectives | Primary behavior change techniques90 |

Theoretical constructs |

Educational messages | Example strategy messagesa | Example personalized feedback messagesb |

| 9 Lessons delivered weekly in fall | ||||||

| 1: How many sugary drinks Do I Drink? |

|

|

|

Sugary drinks include: soda/pop, sweet tea, sports drinks, juices, and energy drinks. Think about which ones you drink. [Infographic link] | Barrier: Habit Wondering where to start breaking your habit? Try keeping a log of when and where you drink sugary drinks. | Parent Meeting Goal – Child Maintained but Not Meeting Goal You drank little to no sugary drinks last week, way to go! [child name] maintained his/her intake. Keep encouraging [child name] to make healthy drink choices! |

| 2: Setting goals and overcoming barriers |

|

|

|

Drink less, live more, throw sugar out the door! Limit sugary drinks to 8 oz. for adults and 0 for kids to improve health for the whole fam. | Barrier: Taste Try diluting your sugary drink with ice or water. This will help you reduce your sugary drink intake AND let you get the taste you crave. | Parent Increased – Child Reduced but Not Meeting Goal [Child name] has decreased his/her intake since last time, but it seems you have increased your intake from last time. Work together as a family to develop a plan, you can always get back on track! |

| 3: Consequences of sugary drinks |

|

|

|

Trying to be healthy? Don't slack, cut back! Drinking fewer sugary drinks can prevent tooth decay, weight gain, and heart problems. Click here to see all the ways sugary drinks can harm your health [Infographic link] | Barrier: Parenting Talk to [Child's name] about reducing sugary drinks and decide on limits together. Make reducing sugary drinks a competition & have fun with it. | Parent Maintained but Not Meeting Goal – Child Reduced but Not Meeting Goal You maintained how much you are drinking and [child name] is drinking less than last time! Keep working to improve your family's drink choices! |

| 4: Using the nutrition facts label to make healthy drink choices |

|

|

|

The nutrition label helps you find the grams of sugar. It tells the truth, unlike logs & pics on the front of the bottle. Click here to see a quick guide to help you practice with your family [Infographic link] | Barrier: Home Environment Next grocery shopping trip, buy half the amount of sugary drinks you normally buy. If drinks finish, that's it till the next trip. | Parent Reduced but Not Meeting Goal – Child Maintained but Not Meeting Goal You have decreased your intake and [child name] has maintained his/her intake. Remember even small decreases in sugary drinks can be a big change for your family's health! |

| 5: Flipping the script on sugary drink marketing |

|

|

|

Sugary drink companies are good at using ads to convince us to buy their stuff. Don't let these companies fool you! | Barrier: Family and Friends You can be a role model to your family and friends! If your family sees you drinking less sugary drinks they will want to drink less too. | Parent and Child Increased You and [child name] have increased your intake since last time. Don't worry, slip-ups happen! Discuss this with your family and develop a plan to get on track with health drink choices! |

| 6: Energy balance, MyPlate & sugary drinks |

|

|

|

Don't drink your calories! Use your calories to eat more fruits and veggies. Click here to see what you could replace with a sugary drink. [Infographic link] | No Barrier: Positive Reinforcement We are so glad to hear that you and your family are keeping up with your goals of drinking fewer sugary drinks. Keep up the good work | Parent Increased – Child Meeting Goal [Child name] is doing great drinking little to no sugary drinks! But it seems you have increased your intake from last time. Discuss tips with [child name] to help get you back on track! |

| 7: Leading sugary drink changes in my community |

|

|

|

[Child's name] knows why and how to drink fewer sugary drinks. Encourage them to become a leader to help others drink less. | Barrier: Habit Figure out where you drink sugary drinks the most, such as going out to eat, and find a healthier choice instead. | Parent Maintained but Not Meeting Goal – Child Meeting Goal [Child name] is drinking little to no sugary drinks, that's awesome! You maintained how much you are drinking. Keep making small changes towards healthy drink choices! |

| 8: Let's write the script! |

|

|

|

[Child's name] created a public service announcement about drinking fewer sugary drink. Ask how s/he likes being a leader for a healthier community. | Barrier: Taste Try to satisfy that sweet tooth with a piece of sugar-free gum instead of sugary drinks. This will curb cravings and keep you on track. | Parent and Child Maintained but Not Meeting Goal You and [child name] have maintained how much you are drinking. Remember even small changes can make big impacts on your health, discuss sugary drink goals with your family! |

| 9: Reflecting on my sugary drink changes |

|

|

|

Set goals to stay on track! Having a goal and a plan to reach it can make it easier to drink fewer sugary drinks. | Barrier: Parenting Make rules around sugary drinks. For example, try to limit [Child's name] sugary drinks to only special events, like parties. | Parent Reduced but Not Meeting Goal – Child Meeting Goal [Child name] is drinking little to no sugary drinks, that's awesome! You have also decreased your intake since last time, keep working to make small changes. |

| 3 Lessons delivered monthly in spring | ||||||

| 10: Sugary drinks & oral health |

|

|

|

Drink less, brush more! Any amount of sugary drinks can cause tooth decay but sipping through the day is worse than drinking it all at once. | Barrier: Home Environment Out of sight, out of mind! Try storing sugary drinks somewhere other than the fridge such as pantry, garage, or basement. | Parent and Child Reduced but Not Meeting Goal Both you and [child name] have cut down your intake from last time. Your family is on the right track, keep trying to reduce your sugary drinks! |

| 11: Saving money by having fewer sugary drinks |

|

|

|

The cost of sugary drinks really adds up! Spending just $1 a day on a pop can add up to $365 over a year. Think of what you can buy instead! [Infographic link] | Barrier: Family and Friends Talk to your family or friends about health risks and benefits of drinking less sugary drinks. This may help motivate them to join you. | Parent Meeting Goal – Child Increased You drank little to no sugary drinks last week, great job! But it looks like [child name] has increased his/her sugary drinks. Discuss this with [child name] and help develop a plan to get on track! |

| 12: Maintaining sugary drink changes |

|

|

|

Congrats on making it to the end! Keep up with your plans and if you slip up don't give up! Ask [Child's name] about “No Guilt, No Giving Up!” | No Barrier: Question What specific parenting rules do you have that help [Child's name] drink less (or no) sugary drinks? | Parent and Child Meeting Goal Congrats! Both you and [child name] drank little to no sugary drinks last week. A healthy family is a happy family, keep up the awesome work! |

Illustrates example strategy messages, actual strategy messages are personalized to caregiver's identified barriers of habit, taste, parenting, home environment, or family and friends.

Illustrates example personalized feedback messages, actual feedback messages are provided every five to six weeks when SSB assessments occur and are personalized to reported SSB behavior change.

Each student receives a workbook with interactive worksheets and info sheets to support lesson delivery and content. In lessons 2, 6, 9, and 12, each student completes a personalized “Drop the Pop!” action plan that includes identifying current sugary drink intake patterns, setting intentions, barriers and strategies for achieving goal(s), and setting SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound) goal(s). Additionally, a self-monitoring section allows students to track and reflect on their goal(s). In lessons 1 and 8, students complete a “Drink Diary,” providing them with the opportunity to track their sugary drink intake outside of class using the knowledge and skills they have gained.

7.2. Caregiver text messages

SMS technology is leveraged to engage caregivers to support decreased SSB behavior through role modeling, home environment, and other changes. Specifically, over a period of 6 months, all enrolled caregivers receive messages two times per week. Messages sent to caregivers are from the following types: assessments, personalized strategy, educational, and educational with an infographic (Figure 3). SMS content is based on the previous adult-focused SIPsmartER trial that used an interactive voice response system to help set goals and identify personalized barriers.48,78 Caregivers have the option to opt-out of receiving text messages should they so desire. Also, at the start of the intervention, all consented caregivers receive a one-time newsletter highlighting key SSB educational, role modeling, and home environment concepts.

Assessment messages collect data on caregiver and student SSB intake, every five to six weeks. The decision to collect data at this frequency is based on considerations of: 1) a relatively longer, 6-month intervention period and 2) obtaining enough data points to monitor trajectories of caregiver and student SSB behavior over time. The assessments consist of three separate messages, delivered consecutively as caregivers respond. Using a one-item question adapted from the Beverage Intake Questionnaire (BEVQ-15),91-93 the first message assesses caregiver intake and the second message obtains student intake. Participants report from seven categories: less than one time, one time, two to three times, four to six times, every day, two per day, or three or more per day. Following this, the SMS software separates participants into four categories based on consumption patterns: caregiver consumer/student consumer, caregiver consumer/student non-consumer, caregiver non-consumer/student consumer, and caregiver non-consumer/student non-consumer. If either student or caregiver is an SSB consumer or has an intake greater than one time per week, caregivers are displayed a message that allows them to indicate a barrier most relevant to them. Subsequently, over the next few weeks, caregivers receive weekly SMS that contain personalized strategies to overcoming their identified specific barriers until the next assessment point (see Table 1). If both caregiver and student are non-consumers, caregivers receive positive reinforcement messages or are asked a question about strategies they use with their own families. The current SMS bank has 59 SSB reduction strategies specific to five SSB barriers: habit (n=11), taste (n=12), parenting (n=11), home environment (n=15), family and friends (n=10).

Educational messages are delivered once per week during the first three months of the program, then once every month during the second three months. The content of educational text messages mirrors the information in the student’s SSB intervention. Some of these educational messages also have a link that takes caregivers to an infographic that reinforces the educational content. Finally, at the follow-up assessment points, personalized feedback is provided based on the reported SSB behavior change among the caregiver and student. Example educational, strategy, and personalized feedback messages are illustrated in Table 1. All SMS have been designed to fit the 160-character limit.

The University of Virginia’s Qualtrics Research Suite is used for SMS delivery and data storage. This university associated delivery tool provides high security for automatically collecting research sensitive information. Additionally, Qualtrics supports customized programming logic to push automated and tailored messages, which reduces researcher burden and error.

7.3. Teacher implementation strategy

A consultation-based implementation strategy was developed to support teachers to deliver Kids SIPsmartER. The strategy incorporates consultation elements identified by Edmunds and colleagues: on-going instruction, self-reflection, and feedback.94 Also, the strategy utilizes in-person and distance learning strategies and allows for self-paced engagement with most implementation strategy components.

First, detailed lesson plans and training videos are available on a secure program website developed for this trial. The Kids SIPsmartER website is designed for easy teacher access, to reduce in-person training and technical assistance burden, and to help standardize the implementation strategy across schools and among teachers. The lesson plans detail procedural steps for delivering the curriculum along with supporting materials. Additionally, each of the 12 lesson plans includes background sections for key content areas covered in the lesson, description of how the lesson activities promote behavior change, detailed activity resources, and PowerPoint slides to support lesson delivery. Teachers receive an educator binder with all printed materials and resources. Lesson training videos complement the written materials. The two curriculum overview and 12 individual lesson training videos provide general and specific information, including suggestions for appropriate adaptations, needed to deliver Kids SIPsmartER. Each video averages about 12 minutes (range 8-20 minutes), for approximately three hours of total training.

Second, the implementation strategy includes training and technical assistance, via in-person and telephone-based options, that are customized to the implementation phase and experience of the teacher. An initial overview training, lasting approximately three hours, will orient teachers to the Kids SIPsmartER program structure, available training resources, co-delivery plan with researchers, informed consent and assent processes, and evaluation components. Notably, the co-teaching responsibilities for teachers in their school’s first year of Kids SIPsmartER program implementation (i.e., Intervention School year or Delayed Intervention School year) is meant to serve as hands-on and content specific training for each lesson. As schools transition into their Support School year and beyond, the training will be tailored meet to specific needs of each teacher. Additionally, teachers can receive telephone-based technical assistance regarding lesson specific and other concerns. The optional ~15 minute telephone calls happen before each lesson and are completed with a research team member specifically assigned to support each teacher. It is anticipated that the demand for training and technical assistance will decrease for teachers who implement the Kids SIPsmartER program in successive years, but will be similar or higher for schools that have teacher turnover.

Third, real-time implementation process data are captured via lessons debrief forms, fidelity observations, surveys and interviews, and field notes (see Section 8.2 for details). Collectively, the implementation process stresses communication, collaboration, and flexibility. This approach allows the teachers to gain the necessary skills and content knowledge to deliver Kids SIPsmartER while recognizing their personal expertise and time constraints. In context of the larger type 1 effectiveness-implementation hybrid design, the goal of the implementation strategy is to balance consistency (e.g. lesson plans, training videos, program website) and flexibility (e.g. training and technical assistance), while standardizing the process evaluation.

8. Data collection and measures

8.1. Individual-level, student and caregiver-level

For students, the validated survey instrument is administered during class time at four time points [baseline, 3-, 7- (immediately post-program), and 19-months (maintenance)]. At 3-months, only the self-reported SSB behaviors are assessed. Each survey assessment data point takes one class period or 45-50 minutes. On a subsequent day, students are pulled from class for height and weight assessments at baseline, 7- and 19-month time points. For caregivers, survey packets are sent home from school to those who have signed a consent to participate in the research at three times (baseline, 7- and 19-months).

Table 2 summarizes the student and caregiver measures for the Kids SIPsmartER trial. For the primary SSB behavior outcome, the Beverage Intake Questionnaire (BEVQ-15), which has been validated in both adults and youth is used,91-93 yet adapted. The BEVQ-15 focuses on frequency and portion sizes of 15 beverage categories, including specific SSB items. To meet the needs of this study, alcohol items were removed and the three types of milk were consolidated into a single milk category, resulting in a 10-item assessment. Importantly, the five items necessary to compute amounts of SSB were not altered (i.e., regular soft drinks, sweetened juice beverage/drink, sweetened tea, coffee with sugar, energy drinks).

Table 2.

Student and caregiver measures for the Kids SIPsmartER trial

| Domains Assessed | Student Measure Description | Caregiver Measure Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Beverage behaviors, including SSB91-93 | 10 beverage categories, frequency and portion sizes | 10 beverage categories, frequency and portion sizes |

| SSB-related Theory of Planned Behavior | 6-item scale on attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions towards SSB1,50,95 | 6-item scale on attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions towards SSB50 |

| Health literacy | 6-item objective assessment of health literacy96-98 | 3-item subjective assessment of health literacy99-101 |

| SSB-related media literacy | 6-item scale covering three subdomains of media literacy framework: authors and audiences, messages and meanings, and representation and reality1,102 | 6-item scale covering three subdomains of media literacy framework: authors and audiences, messages and meanings, and representation and reality102 |

| SSB public health literacy | 4-item measure pertained to student’s perceptions of SSB in their community1,103 | NA |

| Environment | 16-item assessment | 12-item assessment

|

| SSB parenting practices/rules | 12-item assessment on parent’s SSB consumption and parenting rules and practices on SSB23,104 | 17-item assessment on child’s SSB consumption and parenting rules and practices on SSB23,104 |

| Quality of life and other self-rated health | 8-item assessment | 12-item assessment |

| Other health habits | 22-item assessment104,106

|

17-item assessment104,108

|

| Height and weight | Collected and measured by research staff | Self-reported |

| Demographics | 5-item self-reported assessment104,106

|

12-item self-reported assessment104,108

|

The majority of the secondary measures are drawn from previously validated measures with acceptable psychometric properties and were also used in the formative Kids SIPsmartER pilot phases (Table 2). The measures cover the domains of the Theory of Planned Behavior,50,95 media literacy,102 health literacy,96-101 public health literacy,1,103 quality of life and other self-rated health, 105-108 and other health habits.104,106,108,109 For the home environment measure, no appropriate existing measure specific to SSB was available. Therefore, consistent with other measures of home food availability,110,111 questions were constructed using the same beverage items from the BEVQ-15 and three additional food items (i.e., sweets, salty snacks, fruits/vegetables). The frequency of home availability is reported on a 5-point scale, ranging from never to always. Finally, for items pertaining to the frequency of sugary drinks in different settings/situations and for the SSB parenting practices measure, questions were formulated from two different established instruments23,104 and rescaled on consistent Likert scales.

For students, height and weight are measured by trained research staff using a research-grade calibrated digital Tanita scale and portable stadiometer. For caregivers, height and weight is self-reported. BMI percentiles for students and BMI scores for caregivers are calculated using standardized protocol.112

To assess reach, the number, proportion, and demographics of eligible students and caregivers who participate in the research are examined.32,113 The uptake/utilization of SMS among caregivers and SMS process data (e.g. response rate, SSB patterns, SSB strategies selected) is also monitored throughout the trial.

8.2. Organizational, school-level

At the organizational-level, implementation, adoption, and maintenance are assessed.32,113 Relying on best practices in implementation science, implementation process data are captured via lesson debrief forms, fidelity observations, and surveys and interviews with delivery agents. 113-116 Teachers complete lesson debrief forms after each lesson. These written forms include: self-reporting fidelity to lesson content and structure, describing adaptations/modifications, and highlighting good and bad points from the delivery experience. They can be completed on paper or electronically. During the Support Year, a research team member observes about 25% of the 12 lessons (using a convenience sample of lessons). Observations are recorded on a longer version of the lesson debrief form, and feedback is provided to the educator as needed. Teachers complete surveys and interviews after the first nine lessons (~December) and after all lessons have been delivered (~April). Principals also complete a survey and interview after the delivery of lesson 12. These measures capture experiences and perceptions related to implementing Kids SIPsmartER, including identification of barriers, as well as decisions related to program implementation and maintenance. Teachers and principals complete the mixed-methods surveys first so that the research team can incorporate this information into the semi-structured and audio-taped interview.

Additional implementation process measures completed by research staff include field notes and cost tracking. Research staff writes field notes after co-teaching and observing lessons, planning meetings, and interviews meetings with teachers and principals. To track cost, records are maintained related to the cost of lesson and training supplies as well as time spent during research and program implementation activities.

To assess organizational-level adoption, the number and characteristics of the schools approached to participate in this trial are documented, along with reasons regarding their decision to participate. Regarding teacher- and school-level maintenance, the audio-recorded interviews meetings, and process evaluation procedures are used to understand decisions, barriers, and opportunities for maintaining Kids SIPsmartER beyond the support school year.

9. Power calculation and sample size

Given the lack of interventions and designs similar to Kids SIPsmartER,30 data from the Kids SIPsmartER feasibility study were used to estimate the effect size and intraclass correlation (ICC) of students’ SSB intake.1 Considering the school size eligibility criteria and anticipated variation in the number of students per school (range 80-200 students, average 133 students), a lower and upper range of power is estimated. Due to the cluster-randomized block design (i.e., randomization at school level), no attrition at the school level is anticipated. The sample size calculations are conservatively based on a small 7-month effect size of 0.3, a 0.05 type I error, and a 0.01 ICC of students’ SSB intake. To achieve 80% power under these assumptions, a total of 12 schools/clusters (6 schools per condition) are needed, with 54 enrolled students per school (and 49 retained after an anticipated 10% attrition rate at student level at 7-month). Following these same assumptions, 99.99% power would be achieved with a total of 12 schools/clusters and an average of ~115 students enrolled per school (and 104 retained after an anticipated 10% attrition rate). In sum, using conservative effect size and ICC estimates and standard type I error rate, enrolling a minimum of 54 students and up to 115 students per 12 schools/clusters would provide adequate power ranging from 80% to 99.9% for the primary 7-month SSB student outcome.

10. Data analysis

Effectiveness analysis will be on the individual level. Due to the high degree of homogeneity (in income and race) among the eligible schools, focus will be placed on detecting potential selection bias on the individual level program participation and attrition. Appropriate descriptive, parametric, and non-parametric statistical methods will be used to compare continuous and categorical variables among the intervention conditions at baseline. Data will be examined for the presence of outliers, violations of normality for continuous variables, and missing data. Major violations of normality will be corrected with an appropriate transformation procedure. All analysis will use cluster-robust standard error adjustment.

10.1. Primary effectiveness aim

Multi-level mixed effect models will be used to control errors of non-independence and heteroscedasticity caused by individual, class and school heterogeneity, and potential covariates identified a priori based on the literature and theory that are relevant to SSB behavior changes.117,118 The treatment effect models used in this study will contain outcomes of interest as dependent variables (e.g., SSB kcal, quality of life measures etc.). Specific mixed effect link function will be chosen to fit different outcome distributions. The models will control those unobserved effects that are fixed over time at three different levels (i.e., individual student, class, and school) and those unobserved time and block fixed effects that are individual-class-school-invariant. To further examine intervention treatment effect differences across blocks, we will modify the models to allow group indicator to interact with time-block fixed effects.

10.2. Secondary effectiveness, maintenance and reach outcomes

The analytical model for the primary aim will be modified to assess these aims by making the secondary student outcomes the dependent variables. For nonlinear outcomes, such as discrete health literacy classification, appropriate link functions will be used in the multilevel model. Also, the time indicator in the model will be changed to examine effectiveness at 3-month, 7-month, and 19-month. For caregivers’ outcome analysis, a simplified version of the above multilevel mixed effect selection models will be applied, recognizing the class nesting will not be of concern for this level. Furthermore, an additional indicator that signals the uptake of the SMS will be added to the model to examine the adoption of SMS influence on caregivers’ behavior and home environment changes. To further explore student-caregiver dynamics, mixed effect structural equation models will examine the causal relationship among caregiver and student SSB outcome changes. Finally, differences in student effectiveness data will be explored by comparing student level changes within schools when Kids SIPsmartER is co-delivered by researchers-teachers versus when delivered by teachers only.

The program reach at student and caregiver levels will be analyzed following recommendations of Glasgow and colleagues.113 Participation rate at each school will be determined by dividing the total number of 7th grade students and caregivers enrolled by the total number eligible to enroll. Representativeness will be assessed by comparing demographics of students and caregivers eligible and enrolled to the demographic data provided by schools. Uptake/utilization of SMS among caregivers will also be analyzed.

10.3. Organizational, school-level: Implementation, adoption and maintenance

For implementation analyses, quantitative classroom debriefs and observations will be summarized descriptively (i.e., means, variance) and inferential statistics will be used to compare across teachers and schools when sample sizes are sufficient. Interviews from the process evaluation will be audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. A hybrid deductive (i.e., utilizing RE-AIM dimensions) and inductive (i.e., identification of meaning units) qualitative analysis approach will be used to analyze transcripts.119,120 Aided by NVIVO software, meaning units will be identified in each transcript.119 Coding will occur in pairs and 80% agreement will be sought. In an iterative process, the meaning units will be reduced into themes and sub-themes and then organized back to RE-AIM. Finally, to facilitate a deeper understanding of the process, field notes, qualitative, and quantitative data will be triangulated to check for consistency between and within sources. 120-122 For adoption and maintenance, a similar mixed-method approach will be used to compare and document reasons of schools who agree to participate (adoption) in this research project to those who do not wish to participate, as well as compare those who do and do not maintain Kids SIPsmartER beyond the support year.

Implementation costs will be assessed from the program delivery perspective. General cost capture categories will be used to track teachers’ time spent during research, training and implementation activities. Research staff will maintain cost records for lesson and training supplies. Although a cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this project, simple cost metric that sums across categories and specifies school-level costs of adopting and sustaining Kids SIPsmartER will be used.123

11. Discussion

Despite the ubiquitous SSB problem in Appalachia and nationally, as well as clear obesity and health consequences, sustainable solutions surrounding excessive consumption of SSB remains a key public health challenge. Our type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial is the first known study to test the effectiveness of a SSB reduction intervention while simultaneously seeking to actively understand and evaluate the potential for adoption, implementation, and maintenance into existing school systems.30 The RE-AIM framework is one of the most widely used dissemination and implementation frameworks and is an ideal guide for our study that targets both individual-level and organizational-level processes and outcomes.113-116 Pragmatically, our intent is to match a feasible and targeted SSB strategy to the individual resources and environmental capacity of the targeted Appalachian region. Grounded from a health literacy perspective, our Kids SIPsmartER intervention purposefully focuses on an important, yet relatively simple behavior—with a goal of achieving a balance between health literacy skills/ability and demands/complexity of the targeted behavior.124

While a number of evidenced-based health education programs (EBP) are available,125-127 few have established effects in Appalachia and none target SSB intake among Appalachia middle-school students.30 In a recent systematic review of interventions specific to reducing SSB among children, the majority of studies were occurring in schools.30 Though several of these interventions were found to be effective, they rarely focused on implementation factors or sought to engage caregivers. Schools have long been used as venues to support the health of students and their families. This is due, in part, to the overarching mission of public education and the large reach of schools into communities.27 Notably, health education is included within standards of learning. However, standard health education curriculum is limited in its potential effectiveness as it is not behaviorally-focused.128 Unfortunately, schools often face many barriers that hinder implementing health education efforts, such as standardized testing, competing interests with other non-SOL programs, and limited financial resources.27,129 Also, there is limited practical understanding of how to support schools when transitioning from a research-supported paradigm designed to test effectiveness to efforts aimed at promoting long-term adoption, implementation, and maintenance of EBP.27-29 Thus, establishing effectiveness of an SSB intervention within Appalachian schools is a critical first step yet should not be isolated from efforts to understand teacher- and school-level factors that are necessary to sustain effective EBP in schools.

In addition to the important role of schools, there is a wealth of research demonstrating that youth behaviors, 71,72 including SSB behaviors,21-26 are heavily influenced by their caregivers and home environment. Notably, youth develop and maintain SSB behavior through parental modeling and reinforcement. Middle school aged students are at a critical time for increased autonomy in food/beverage choices; however, caregivers largely remain the gatekeeper for the home environment, maintain the majority of purchasing power, and are one of the strongest role models for their child.21-26 Therefore, interventions seeking to create lasting change in youth SSB consumption, including those implemented in schools,130 must also target and engage their caregivers.

The use of an integrated SMS technology strategy to engage caregivers in improving their child’s SSB behaviors is an innovative design feature of our Kids SIPsmartER intervention. Text messaging is the most common mode of communication for over 7 billion users worldwide and is an efficient, cheap, and personalized means of communication. This makes SMS an easily scalable component for behavioral intervention. Importantly, numerous reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate the impact of SMS on changing health behaviors,86-89 including some preliminary research that found SMS is a useful component in interventions aimed at decreasing SSB consumption in children.131 Past research has found that SMS is a valid and practical way of collecting data and is endorsed and well-accepted by caregivers as a convenient method of data collection.132 Additionally, prior studies have found that some tailoring of SMS to individuals is generally preferred and increases intervention engagement.89,133 Despite the promise of SMS, little is known about the utility of SMS as a school-based intervention component in rural communities. Our study will provide important data on the reach, engagement, and effectiveness of a tailored SMS intervention targeting caregivers of middle school students’ caregivers in rural communities.

Finally, it is important to situate Kids SIPsmartER from a larger ecological perspective, including macro-level influences. Due to recent mandates that restrict the sales of SSB during regular school hours,134-136 excessive SSB consumption rarely occurs during regular school hours. Published literature also shows that the majority of SSB consumption among children and adolescents occurs at home, and not during regular school hours.13,137 As such, when targeting SSB behaviors, macro-level school-based strategies are of lower priority relative to other influences. Also, some US cities have also had success with SSB taxation at the community level.138,139 Unfortunately, similar to many US disparity-related issues; poor, rural subpopulations with the highest odds of heavy SSB consumption (like Appalachians) also have fewer opportunities to benefit from SSB taxation. It takes tremendous local leadership, public will, and financial resources to fight the powerful American Beverage Association opposition.140,141 For example, it takes cities an estimated $2.5-$5 million to support and pass a SSB tax, and the American Beverage Association outspends these efforts by over 3-4 times.142 To our knowledge, there has been zero political action for SSB taxation in our targeted Appalachia counties. From a cultural perspective, long-standing and engrained SSB behaviors will likely not be solved solely from a top-down approach. Behavioral programs, similar to Kids SIPsmartER, are generally viewed as more acceptable, met with less political opposition, and are regarded as a necessary complement to macro-level strategies. Importantly, our long-term vision and impetus behind the Kids SIPsmartER curriculum strategies (e.g. media literacy, public health literacy) are to educate and empower youth to recognize the influence of Big Soda, as well as teach advocacy skills and encourage civic action.

12. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the unique rural Appalachia schools targeted by our research efforts may limit the generalizability of our findings beyond this region. Second, given that our trial is targeting real-world school systems, there are several key structural factors that may vary across schools and have the potential to influence study findings (e.g. class size, teacher-to-student ratios, inconsistency in students’ semester schedules, level of commitment or involvement of teachers and upper administration, level and regularity of training and technical assistance needed or requested). However, our mixed-methods implementation process data are designed to identify these differences and to assist in the interpretation of findings. Third, despite efforts to minimize selection bias through the randomization and consent processes, neither the teachers nor researchers who are involved in the recruitment process are blinded to schools’ randomized allocation. This may introduce bias in the proportion of consented caregivers and students between Intervention Schools and Control Schools,73 even though similar recruitment efforts and protocol are applied at each school. Fourth, we acknowledge that not all caregivers will opt-in to receive the SMS and some caregivers will opt-in and later drop out. This is an issue of all SMS trials and one that we seek to better understand through our proposed reach and effectiveness analyses. Despite these limitations, our hybrid design and multi-level study is strategically planned to optimize attention to both internal and external validity, address major gaps in the literature, accommodate key practical needs of the schools, and accelerate research through the pipeline.114,116,143,144

13. Conclusions

Excessive SSB consumption among Appalachians is well-established, along with clear associations among SSB and numerous chronic health conditions.7-15 The long-term goal of this line of health promotion and prevention research is to sustain effective strategies to reduce SSB-related health inequities and chronic conditions in rural Appalachia. As such, collaborating with local Appalachian school systems to evaluate multi-level SSB intervention strategies among middle-school students and their caregivers has important public health implications. If found to be effective and if implementation at the school level shows strong potential, Kids SIPsmartER could be scaled-up to reach and extend the benefit to additional middle schools in Appalachia and beyond.

Acknowledgements:

We would like the acknowledge the superintendents and middle school principals from Tazewell and Buchannan county, for their time and dedication in the study planning process, and with a distinct recognition for the efforts of Superintendent Mr. George Brown. We also appreciate the insightful guidance provided by Dr. Deborah Tate on the caregiver SMS component.

Funding Sources: This study was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [R01MD012603]. NIH was not involved is the design of this study or writing of this manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- SSB

sugar-sweetened beverages

- SMS

short service message

- RE-AIM

reach, adoption, effectiveness, implementation, and maintenance

- BMI

body mass index

- TPB

Theory of Planned Behavior

- VDH

Virginia Department of Health

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- EBP

evidenced-based programs

Footnotes

Identifiers: Clincialtrials.gov:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lane H, Porter K, Hecht E, Harris P, Zoellner J. Kids SIPsmartER: a feasibility study to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among middle school youth in Central Appalachia. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(6):1386–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zoellner J, Krzeski E, Harden S, Cook E, Allen K, Estabrooks PA. Qualitative application of the theory of planned behavior to understand beverage consumption behaviors among adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012; 112(11):1774–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Park S, Nielsen SJ, Ogden CL. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999-2010, Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popkin BM, Armstrong LE, Bray GM, Caballero B, Frei B, Willett WC. A new proposed guidance system for beverage consumption in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(3):529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kit BK, Fakhouri THI, Park S, Nielsen SJ, Ogden CL. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999–2010. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedrick VE, Davy BM, You W, Porter KJ, Estabrooks PA, Zoellner JM. Dietary quality changes in response to a sugar-sweetened beverage–reduction intervention: results from the Talking Health randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(4):824–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imamura F, O'Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ. 2015;351:h3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Edmonds PJ, et al. Sugar and artificially sweetened soda consumption linked to hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2015;37(7):587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernabe E, Vehkalahti MM, Sheiham A, Aromaa A, Suominen AL. Sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries in adults: a 4-year prospective study. J Dent. 2014;42(8):952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodge AM, Bassett JK, Milne RL, English DR, Giles GG. Consumption of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soft drinks and risk of obesity-related cancers. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(9):1618–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Light K, Henderson M, et al. Consumption of added sugars from liquid but not solid sources predicts impaired glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance among youth at risk of obesity. J Nutr. 2013;144(1):81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988-2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1604–e1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington S The role of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in adolescent obesity: a review of the literature. J Sch Nurs. 2008;24(1):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller A, Bucher Della Torre S. Sugar-sweetened beverages and obesity among children and adolescents: a review of systematic literature reviews. Child Obes. 2015;11(4):338–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halverson JA, Friedell GH, Cantrell SE, Behringer BA. Health Care Systems In: Ludke RL, Obermiller PJ, eds. Appalachian Health and Well-Being. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGarvey EL, Leon-Verdin M, Killos LF, Guterbock T, Cohn WF. Health disparities between Appalachian and non-Appalachian counties in Virginia USA. J Community Health. 2011;36(3):348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behringer B, Friedell G. Appalachia: where place matters in health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(4):A113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Department of Agriculture ERS. Food Access Research Atlas website. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/. Updated May 18, 2017 Accessed May 15, 2017.

- 20.Howley A, Wood L, Hough B. Rural Elementary School Teachers' Technology Integration. Journal of Research in Rural Education. 2011;269:1–13. http://jrre.psu.edu/articles/26-9.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Ober AJ, et al. Home sweet home: parent and home environmental factors in adolescent consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. Acad Pediatr. 2017; 17(5):529–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Sharma AJ, et al. Parental and home environmental facilitators of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among overweight and obese Latino youth. Acad Pediatr. 2013; 13(4):348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van de Gaar VM, van Grieken A, Jansen W, Raat H. Children’s sugar-sweetened beverages consumption: associations with family and home-related factors, differences within ethnic groups explored. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickelson J, Roseman MG, Forthofer MS. Associations between parental limits, school vending machine purchases, and soft drink consumption among Kentucky middle school students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42(2):115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]