Abstract

Dentin dysplasia (DD) is an uncommon developmental disturbance affecting dentin, resulting in enamel with atypical dentin formation and abnormal pulpal morphology. Type I (radicular) and Type II (coronal) are the two types of DD. Type I is more common, and both types include single or multiple teeth in primary and permanent dentition. Combinations of both types have also been described in literature. Four distinct forms of Type I and one form of Type II were identified. This case report documents one such rarity of DD in an 11-year-old female with clinical and radiographical findings and management aspects.

Keywords: Atypical dentin, dental anomaly, dentin dysplasia, pulp obliteration, pulp stones, rootless teeth

INTRODUCTION

Developmental anomalies are quite uncommon and can affect enamel and/or dentin portion of developing teeth. The presence of teeth anomalies can result in esthetic, psychological and functional problems. Dentin is a mineralized tissue which forms the body of the tooth, serving the pulp as a protective cover and supports both overlying of enamel and cementum.[1] Dentin dysplasia (DD) is a rare developmental anomaly of dentin characterized by normal enamel and crown morphology, having atypical dentin formation, abnormal pulp morphology and small roots.[2] DD, so named by Rushton, was first described by Balchsmiede as rootless teeth. It manifests in both primary dentition and permanent dentition with a prevalence of 1 in 100,000.[3]

The rare anomaly of DD with unknown etiology has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. DD occurs in a number of disorders such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, calcinosis, branchio–skeleto–genital syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, Vitaminosis D and in osseous changes along with sclerotic bone formation.[4,5,6] DD was also reported in association with taurodontism.[7,8]

DD can be classified as (i) radicular and coronal DD, (ii) Type I and Type II DD and (iii) generalized (>30% affected) or localized (<30% affected).[4,8] Carrol et al. proposed a subclassification based on the radiographic findings. Type I was classified into four subtypes: 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d [Table 1].[4]

Table 1.

Carrol et al. classification of dentin dysplasia Type I[4]

| DD types | Features |

|---|---|

| Type Ia | Complete obliteration of pulp chamber, little or no root development |

| Type Ib | Single crescent-shaped horizontal radicular line with abnormal radicular dentin, rudimentary root |

| Type Ic | Two crescent-shaped horizontal radicular lines with one half of root length and absence of canals |

| Type Id | Normal root formation with bulbous coronal one-third, pulp stone with healthy pulp |

DD: Dentin dysplasia

Clinically, DD Type I affects teeth in both dentitions (primary and permanent) and have normal size, shape, color and enamel formation or slightly amber translucency with nearly normal-appearing crowns.[4,5,9] The teeth may be prematurely exfoliated due to their short roots and periapical lesion or lost as a result of trauma. Tooth eruption is usually unaffected and they are resistant to dental caries.[4,9,10] Histologically, it shows normal dentinal tubule which can appears to be blocked with new dentin forms around the obstacles, resulting in lava flowing around boulders.[6,11] Because mantle dentin is not affected, the teeth have an apparently normal clinical crown.[11] There is normal-appearing mantle dentin and globular or nodular masses of abnormal dentin.[4] Short conical roots with partial obliteration of coronal chamber and total obliteration of pulp canals are seen radiographically in DD Type I.[9] In DD Type I, osseous changes with sclerotic bone formation can be seen.[6]

In DD Type II, clinically, both dentitions are affected. Primary teeth will give a brown amber or bluish translucent and appearance similar to dentinogenesis imperfect. The permanent tooth will have normal appearance or slight amber discoloration.[11] Radiographically, primary teeth show total obliteration of pulp while the permanent teeth show thistle tube pulp configuration and the presence of pulp stone in pulp chamber, and the roots are normal in size and shape.[9,11] DD has to be differentiated from other conditions such as dentinogenesis imperfecta and regional odontodysplasia.[6]

CASE REPORT

An 11-year-old female patient reported to the Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry with a chief complaint of broken upper front tooth for 1 month. She gave a history of trauma to the tooth due to fall from a bicycle. Her medical and family history was noncontributory. Informed consent was obtained from parents of the child.

Extraoral examination revealed no abnormality. Intraoral examination revealed poor oral hygiene with plaque and calculus deposits. The patient had mixed dentition with decayed 16, 55, 26, grossly decayed 75, root stump 74, 83, retained 52, palatally erupting 12 and filled 46. Teeth 11 and 21 showed Ellis Class II fracture [Figure 1]. Crown portion of all teeth were of normal size, morphology and color. Teeth eruption was normal.

Figure 1.

Intraoral photograph showing Ellis Class II fracture with respect to 11 and 21 with normal color, texture and shape of teeth

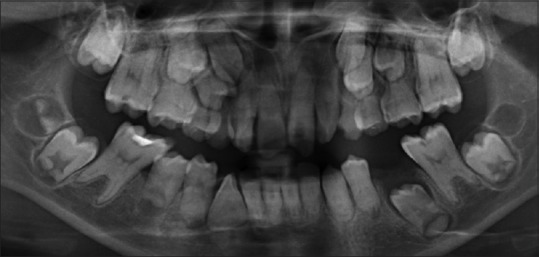

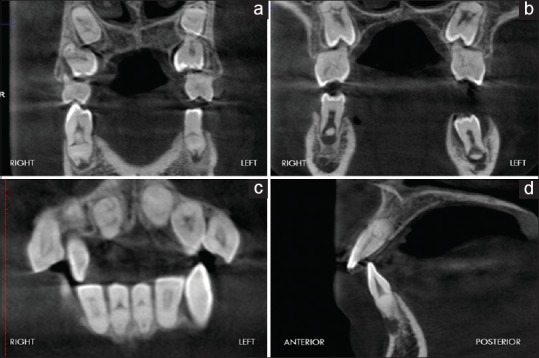

Intraoral periapical radiograph [Figure 2] and panoramic radiograph [Figure 3] examination revealed the presence of short/incomplete or malformed root in most of the teeth. There was abnormal pulpal morphology with obliteration of pulp along with pulp stones [Figure 4]. Permanent molars showed apical migration of furcation area showing taurodontism-like appearance. There were many accessary canals and abnormal ramification in permanent maxillary incisors. On the basis of clinical and radiographic evaluation, a diagnosis of DD Type-I was confirmed (which is affecting the roots only). Decayed teeth were restored with Type IX glass ionomer cement; grossly decayed 74, 75, 83 teeth were extracted under local anesthesia.

Figure 2.

Radiovisiography showing obliterated pulp chambers and crescent-shaped pulp chambers having dentinal mass in the middle third of the root with defective root formation (a) upper incisors and (b) lower incisors

Figure 3.

Orthopantomogram showing generalized dentin dysplasia Type I with obliterated pulp chambers with short/absence of roots with pulp stone and taurodontism-like appearance in molars

Figure 4.

Cone-beam computed tomography scan of dentin dysplastic teeth showing the obliterated crescent-shaped pulp chambers with pulp stones defective root formation. (a) Coronal section of the 1st premolar, (b) coronal section of the 2nd premolar, (c) coronal section of lower anteriors, and (d) sagittal section of 42

DISCUSSION

DD is an uncommon developmental anomaly affecting dentin, resulting in short root, mobility and early exfoliation; hence, early diagnosis and multidisciplinary management is necessary. Preventive care is of foremost important for patients with DD with rubber cup pumice prophylaxis and topical application of 1.23% acidulated phosphate fluoride gel. Instructions on oral home care are reinforced, and the affected regions are examined both clinically and radiographically at regular intervals.[8] Loss of periodontal attachment may be adequately prevented through effective oral hygiene. The patient's oral hygiene should be monitored to prevent possibility of early exfoliation due to periodontal inflammation.[10] Prophylactic stainless steel crown is used to prevent tooth wear and maintain occlusal vertical dimension.[12]

There is no specific treatment for this rare genetic disorder affecting the dentin development of teeth. It is wise to control mobility of tooth and minimize discomfort during mastication and retain teeth as long as possible. The prognosis depends on the occurrence of lesion in the periapical region that necessities extraction of teeth. Only procedures to avoid the premature loss of hypermobile teeth and to simulate the normal development of the occlusion can be undertaken. Because the affected teeth have a very unfavorable prognosis due to the short roots and the presence of associated periapical radiolucencies, careful monitoring is mandatory. If necessary, space loss due to spontaneous exfoliation of hypermobile teeth can be managed by the placement of removable space maintainers.[13] Composite facing/composite strip crown can be added for esthetic reason on demand.[14]

Because of the peculiar pulpal morphology (abnormal ramification) and pulp stones, endodontic therapy is challenging. Because of ramification and pulp stones, there is difficulty in instrumentation and obturation. Hence, teeth with long roots requiring endodontic therapy can be treated by periapical curettage and retrofilling, rather than conventional endodontic therapy.[10,12]

If any orthodontic treatment is needed, very light forces should be used for prolonged period of time with maximum extraoral forces.[13] Orthodontic forces may cause further resorption of roots and loosening of teeth, and premature exfoliation may occur due to resistance of the short roots to these forces.[14] Extraction should be performed in cases involving periapical infection, mobility followed by replacement prosthesis.[3,15] If the teeth have undergone attrition to the level of the gingiva and the only treatment option left is to provide overdenture.[3] Until the growth is complete, the treatment of choice for the placement of missing teeth is denture. Dental implants may be considered when the growth is complete at about 18 years of age. Hence, the treatment in DD varies according to the age of the patient, severity of the problem and presenting complaint.[12]

In the present case, there was a presence of ramification in maxillary incisors and taurodontism-like appearance in molars, which makes endodontic treatment difficult and needs modified aspect. According to Witkop, taurodontism is more likely an anomaly arising from a failure of sufficient invagination of Hertwig's Epithelial Root Sheath and not an intrinsic defect in dentin formation.[5] In our case, there was Ellis Class II fracture with relation to upper incisors 11 and 21, which was restored with composite and the rest of all teeth had normal clinical crown portion. The patient and her parents were informed about the condition and preventive measures. Because the patient was not having any complication, she was kept under recall visits.

CONCLUSION

The pediatric dentist has an important role in the early diagnosis of this disorder and in guiding the patient in the selection of measures to prolong the retention of affected teeth. Treating DD patient is a challenge to all clinicians because treatment may not be successful always; however, treatment attempts are made to allow these abnormal teeth to be retained instead of extraction and replacement with dentures.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim JW, Simmer JP. Hereditary dentin defects. J Dent Res. 2007;86:392–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozer S, Ozden B, Otan Ozden F, Gunduz K. Dentinal dysplasia type I: A case report with a 6-year followup. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:659084. doi: 10.1155/2013/659084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khandelwal S, Gupta D, Likhyani L. A case of dentin dysplasia with full mouth rehabilitation: A 3-year longitudinal study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2014;7:119–24. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toomarian L, Mashhadiabbas F, Mirkarimi M, Mehrdad L. Dentin dysplasia type I: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witkop CJ., Jr Hereditary defects of dentin. Dent Clin North Am. 1975;19:25–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik S, Gupta S, Wadhwan V, Suhasini GP. Dentin dysplasia type I – A rare entity. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015;19:110. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.157220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosinski RW, Chaiyawat Y, Rosenberg L. Localized deficient root development associated with taurodontism: Case report. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:213–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocha CT, Nelson-Filho P, Silva LA, Assed S, Queiroz AM. Variation of dentin dysplasia type I: Report of atypical findings in the permanent dentition. Braz Dent J. 2011;22:74–8. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402011000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shields ED, Bixler D, el-Kafrawy AM. A proposed classification for heritable human dentine defects with a description of a new entity. Arch Oral Biol. 1973;18:543–53. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(73)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steidler NE, Radden BG, Reade PC. Dentinal dysplasia: A clinicopathological study of eight cases and review of the literature. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;22:274–86. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(84)90084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seow WK, Shusterman S. Spectrum of dentin dysplasia in a family: Case report and literature review. Pediatr Dent. 1994;16:437–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barron MJ, McDonnell ST, Mackie I, Dixon MJ. Hereditary dentine disorders: Dentinogenesis imperfecta and dentine dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenneise CV, Dwornik RM, Brenneise EE. Clinical, radiographic, and histological manifestations of dentin dysplasia, type I: Report of case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;119:721–3. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1989.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravanshad S, Khayat A. Endodontic therapy on a dentition exhibiting multiple periapical radiolucencies associated with dentinal dysplasia type 1. Aust Endod J. 2006;32:40–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2006.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shankly PE, Mackie IC, Sloan P. Dentinal dysplasia type I: Report of a case. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1999;9:37–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.1999.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]