Abstract

Outcomes associated with magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have been reported, however the optimal population for MSA and the related patient care pathways have not been summarized. This Minireview presents evidence that describes the optimal patient population for MSA, delineates diagnostics to identify these patients, and outlines opportunities for improving GERD patient care pathways. Relevant publications from MEDLINE/EMBASE and guidelines were identified from 2000-2018. Clinical experts contextualized the evidence based on clinical experience. The optimal MSA population may be the 2.2-2.4% of GERD patients who, despite optimal medical management, continue experiencing symptoms of heartburn and/or uncontrolled regurgitation, have abnormal pH, and have intact esophageal function as determined by high resolution manometry. Diagnostic work-ups include ambulatory pH monitoring, high-resolution manometry, barium swallow, and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. GERD patients may present with a range of typical or atypical symptoms. In addition to primary care providers (PCPs) and gastroenterologists (GIs), other specialties involved may include otolaryngologists, allergists, pulmonologists, among others. Objective diagnostic testing is required to ascertain surgical necessity for GERD. Current referral pathways for GERD management are suboptimal. Opportunities exist for enabling patients, PCPs, GIs, and surgeons to act as a team in developing evidence-based optimal care plans.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Surgery, Magnetic sphincter augmentation, Referral pathways

Core Tip: While the outcomes associated with magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have been previously reported, the optimal population for MSA and the related patient care pathways have not been summarized. This review presents evidence that describes the optimal patient population for MSA, delineates diagnostics to identify these patients, and outlines opportunities for improving GERD patient care pathways. Current referral pathways for GERD management are suboptimal. Opportunities exist for enabling patients, primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and surgeons to act as a team in developing evidence-based optimal care plans.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an inherently mechanical disease whose primary etiology lies in a weakened lower esophageal sphincter (LES)[1-5] which opens abnormally and allows the reflux of gastric content into the esophagus. The opening of the LES and reflux result from changes in gastric fluid pressure relative to abdominal pressure regulated by adjustments in the anatomical conformation of the sphincteric muscles[6]. Additionally, it is contended that the crura contribute to the competence of the anatomic anti-reflux mechanism[7-11]. The presence of a hiatal hernia adversely affects LES pressure, relaxation, and esophageal acid clearance. Furthermore, the frequency and duration of acid exposure in the esophagus is significantly impacted by the incidence of transient LES relaxations (tLESRs), and patients need to be considered for treatment with these mechanical aspects in mind[12-14].

Based on disease severity and responsiveness to medical management, some patients with GERD may benefit from surgical intervention. However, effective treatment of patients with GERD requires an awareness of the clinical spectrum of GERD, its varied symptomatology and potential complications, the reasons for referral, and the many treatment options available[15,16]. Sub-optimal referral of patients may affect the process of patient evaluation, treatment, and continuity of care, and can affect clinical outcomes and costs[17]. Despite multiple treatment options, a considerable number of patients with GERD have inadequate disease management[18]. GERD is inherently a multi-specialty disease and in order to ensure that the appropriate interventions are delivered efficiently, a better understanding of GERD patient care pathways is needed[19].

Treatment options for GERD vary depending on the progression and symptoms of their disease, however, there are currently three primary means of treating GERD: lifestyle changes, medical therapy, and surgical intervention[20]. Lifestyle interventions should be included as part of the therapy for GERD[15]. Counseling is often helpful to provide information regarding weight loss, head of bed elevation, tobacco and alcohol cessation, avoidance of late-night meals, and cessation of foods that can potentially aggravate reflux symptoms including caffeine, coffee, chocolate, spicy foods, highly acidic foods such as oranges and tomatoes, and foods with high fat content[15]. While medical therapy with anti-acid medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is the mainstay of treatment that can control heartburn in the majority of patients, other symptoms such as regurgitation and respiratory symptoms may not be controlled, particularly in patients with compromised LES and/or hiatal hernias[2,21-23]. Although external factors such as inadequate dosing or nonadherence to treatment may play a role in PPI failure, persistent GERD symptoms despite anti-secretory drugs may be indicative of an incompetent LES that allows abnormal reflux of gastric content into the esophagus[1-5]. Endoscopic therapies for GERD have been developed but evidence for their long-term efficacy is limited[15]. These include radiofrequency augmentation to the LES, silicone injection into the LES, and endoscopic suturing of the LES[15]. Recent alternative approaches have included transoral incisionless fundoplication, a suturing device designed to create a full thickness gastroesophageal valve from inside the stomach[15]. Unfortunately, long-term data regarding efficacy of this device are limited to a small number of subjects and short duration of follow-up[15].

Anti-reflux surgery is an option to better control symptoms and avoid lifelong medical therapy[24]. Currently, the de facto treatment option for surgical treatment of GERD is the laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication (LNF) procedure[25]. LNF involves wrapping a portion of the stomach around the esophagus to reinforce the weakened LES. While LNF has long been associated with effective reflux control, it has several limitations: (1) It results in anatomical and physiological alteration of the fundus; (2) Potential side effects including gas bloat and an inability to belch or vomit may occur[5,26]; and (3) The procedure is difficult to standardize and teach, resulting in variable efficacy[26,27]. Sixty-seven percent of patients undergoing LNF (54/87) reported new symptoms (i.e., excessive gas, abdominal bloating, dysphagia) after surgery[28]. LNF is associated with up to 15% reoperation rates and a cumulative surgery failure rate of up to 27.1%[26,29].

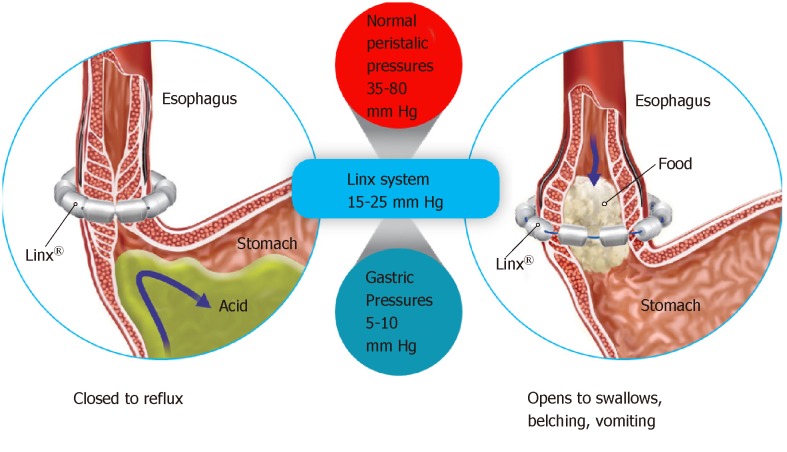

An alternative to LNF is Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation (MSA). MSA with the LINX® Reflux Management System was FDA approved via the premarket approval (PMA) process and has shown beneficial effects in studies in diverse patient populations[27,30-44]. The LINX Reflux Management System is a laparoscopic, fundic-sparing anti-reflux procedure indicated for patients diagnosed with GERD as defined by abnormal pH testing, and who are seeking an alternative to continuous acid suppression therapy (i.e., PPIs or equivalent) in the management of their GERD. LINX is contraindicated in patients with suspected or known allergies to titanium, stainless steel, nickel, or ferrous materials. LINX is an implantable device consisting of a series of titanium beads, each containing a magnetic core connected with independent titanium wires that allows dynamic augmentation of the LES without compression of the esophagus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

LINX magnetic sphincter augmentation implantable device.

The magnetic attraction of the device is designed to close the LES immediately after swallowing, restoring the body's natural barrier to reflux. Warren et al[45] demonstrated how a manometrically defective LES can essentially be restored to a normal sphincter with MSA, thus reestablishing the mechanical barrier to reflux. Compared to baseline, studies of patient outcomes with MSA have reported excellent pH control with more than 50% of patients normalizing pH scores at 1 year, and significant improvements in symptom scores and PPI usage at the 5-year interval[31,33,42]. A randomized control trial (RCT) compared LINX to twice-daily (BID) 20 mg omeprazole PPI demonstrated significant relief from regurgitation with LINX therapy compared to patients in whom the PPI dosage was increased from single to double-dose[44]. Overall, MSA has been demonstrated to be potentially safe and efficacious, reversible and reproducible, and associated with fewer side effects compared to LNF[30-41]. Importantly, MSA patients experienced improvement in regurgitation, PPI dependence, heartburn, and patient satisfaction that persisted for 5 years[30,35,40,44]. More than 75% of MSA patients experienced complete cessation of PPI use at up to 5 years[30,32-34,40,44,46,47]. The 5-year reoperation rate with MSA has been shown to range from 6.8%-7.0%[30,33]. The most common side effects of MSA were gas/bloating (26.7% with MSA vs 53.4% with LNF; P = 0.06) and postoperative dysphagia (33.9% with LINX vs 47.1% with LNF; P = 0.43)[35]. When performed responsibly and on appropriately-selected patients, MSA can be an important treatment to optimally control these patients’ reflux disease, thereby increasing their quality of life, and minimizing potential side effects.

In regards to the economic consequences associated with MSA, a meta-analysis by Chen et al[48] showed that MSA had a significantly shorter operative time (MSA and fundoplication: RR = -18.80 min, 95%CI: -24.57 to -13.04, and P = 0.001) and length of stay (RR = -14.21 h, 95%CI: -24.18 to -4.23, and P = 0.005) compared to fundoplication. A retrospective analysis of 1-year outcomes of patients undergoing MSA and LNF by Reynolds et al[36] showed that LNF and MSA were comparable in overall hospital charges ($48491 vs $50111, P = 0.506). The charge for the MSA device was offset by lower charges in pharmacy/drug use, laboratory/tests/radiology, OR services, anesthesia, and room and board. There were significant differences in OR time (66 min MSA vs 82 min LNF, P < 0.01) and LOS (17 h MSA vs 38 h LNF, P < 0.01).

While the outcomes associated with MSA have previously been evaluated, evidence describing the optimal population for MSA and the related GERD patient pathways have not yet been summarized. Proper patient selection is central to obtaining the best possible surgical outcomes in patients with GERD[5,15,19,49]. As such, the purpose of this review is to (1) Describe the optimal population for MSA; (2) Delineate the diagnostic evaluation necessary to identify those patients; and (3) Assess gaps in patient care pathway and identify opportunities to improve care coordination.

A narrative literature review was undertaken to obtain a comprehensive and critical analysis of the current knowledge on the topic.

Data sources and searches

Comprehensive searches of the literature were performed using the Medline (PubMed) and EMBASE databases with the timeframe of January 1, 2000 to December 16, 2018. A search for guidelines available from the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGS) was also conducted. Search terms utilized in the literature search included: “gastroesophageal reflux disease”, “GERD”, “refractory”, “surgery”, “magnetic sphincter augmentation”, “LINX”, “fundoplication”, “Nissen”, “pH monitoring”, “manometry”, “lower esophageal sphincter”, and “mechanical”. Reference lists of selected studies were also reviewed for possible additional articles.

Study selection criteria

Study and guideline inclusion criteria were publications that presented evidence for current treatment pathways of patients with GERD. Exclusion criteria included publication of abstracts only, case reports, letters, or commentaries; animal studies; languages other than English; duplicate studies; and studies that did not evaluate the patient population of interest (e.g., malignancy, any form of esophageal dysmotility, achalasia and scleroderma). After removing excluded abstracts, full articles were obtained, and studies were screened again more thoroughly using the same exclusion criteria. A total of 86 articles were identified for inclusion in this narrative review. Studies were assessed for quality; the study types (designs) used to address the research questions were: Level I – randomized controlled trials; Level II – prospective, non-randomized trials; Level III – retrospective comparative studies; Level IV – single-arm case series; and Level V – expert opinion.

FINDINGS-TARGET POPULATION AND REFERRAL PATHWAYS FOR MSA

Describing the target population potentially eligible for anti-reflux surgery

GERD can have significant potential complications such as erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma[50]. Persistent reflux symptoms, despite PPI therapy, have been associated with debilitating comorbidities including mental health disorders, sleep disorders, and psychological distress to patients[51,52]. Additionally, GERD is known to negatively impact health related quality of life, work productivity, and overall healthcare resource utilization[53].

While there is evidence that acid-suppressive drugs reduce the acidic content of refluxate, abnormal reflux continues and associated symptoms such as regurgitation and respiratory symptoms are often not controlled with medical management[54]. Between 30%-40% of patients on PPI therapy (even those on double-dose therapy) continue to experience heartburn or regurgitation symptoms despite adequate healing of esophagitis[55]. Treatment in clinical practice has been primarily focused on increasing escalation of the PPI dose and/or frequency, or supplementing with additional anti-acid medications[56]. In patients who failed twice daily PPI, alternative treatments range from lifestyle and diet modification, weight loss, medical treatment with a focus on controlling the frequency of tLESRs, attenuating esophageal pain perception using visceral analgesics, cognitive behavior therapy, and anti-reflux surgery[56]. As symptoms of GERD become increasingly severe and burdensome to the patient despite various treatment approaches, patients may be advised to seek, or may refer themselves for, surgical therapy[2,23,57].

A search of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)'s National Guideline Clearinghouse[58] identified two clinical guidelines evaluating surgery for GERD: the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2013 Guidelines[23] and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) 2012 Guidelines[59]. Both guidelines agree that: (1) Surgery is a treatment option for patients with chronic reflux and refractory symptoms; (2) Surgical therapy is generally not recommended for patients who do not have at least a partial response to acid reduction therapy; and (3) Surgery appears to be more effective in patients with typical symptoms of heartburn and/or regurgitation than in patients with extraesophageal or atypical symptoms[23,59].

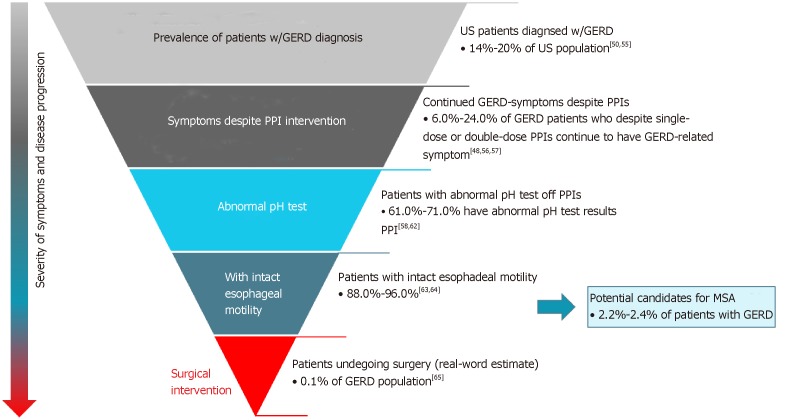

Reasons to refer GERD patients for surgery, including MSA, may include persistent symptoms despite medical therapy, desire to discontinue medical therapy, or presence of a large hiatal hernia[2,23,42]. It is important that MSA candidates have normal esophageal motility documented by high resolution manometry. This is to ensure enough esophageal power to break the magnetic bonds and allow the device to open, allowing for normal swallowing[23]. Potential surgical candidates for MSA are those GERD patients (14-20%[57] of U.S. population[60]) who, despite optimal medical management, continue to experience symptoms of heartburn and/or uncontrolled regurgitation [medically managed and refractory to lifestyle and pharmacological interventions (6.0%-24.0%)[22,55,61,62]], have abnormal pH off PPI (61.0%-71.0%)[63-67], and do not have esophageal dysmotility (88.0%-96.0%)[68,69]. Overall, among patients with GERD, the total eligible population for MSA is estimated to be in the 2.2%-2.4% range (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Typical eligibility criteria for anti-reflux surgery procedures as patients progress from medical management to surgery.

Currently, it is estimated that only 0.1% of GERD patients[70] in fact undergo anti-reflux surgery. The reasons underlying the significant gap are multifactorial and would benefit from a more well-defined care pathway. Additional reasons to refer GERD patients for surgery include the desire to discontinue medical therapy, non-compliance, side-effects associated with medical therapy, and the presence of a large hiatal hernia[23,71]. In practice, patient identification and treatment are based on a combination of the guidelines[23,71], a robust preoperative work-up, and ultimately, physician assessment of patient symptoms and disease severity.

DIAGNOSTICS TO DETERMINE SURGICAL ELIGIBILITY OF GERD PATIENTS

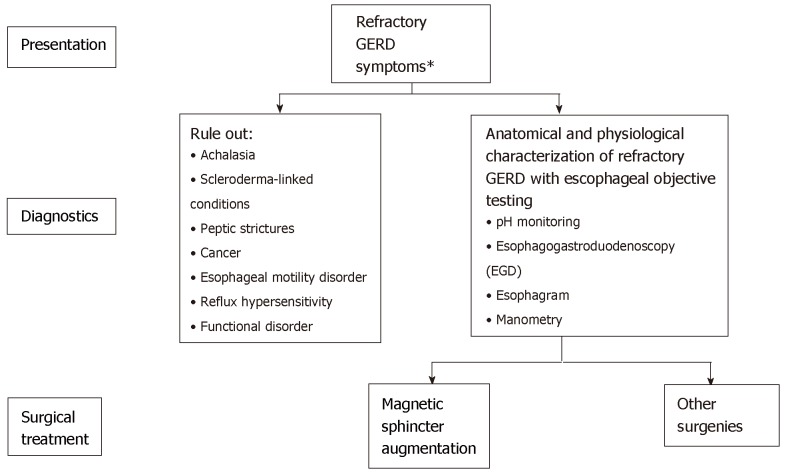

In order to appropriately identify those patients who might benefit from anti-reflux surgery, it is important that thorough testing be performed. Objective testing is required to confirm the diagnosis of GERD in patients being considered for surgery. Diagnostic testing is recommended for patients with GERD who do not respond to prior treatments, have symptoms suggestive of complications or other conditions (e.g., dysphagia, odynophagia, bleeding, anemia, weight loss), or are at risk for developing Barrett’s esophagus[23]. Typical pre-operative diagnostic testing includes esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), ambulatory pH monitoring, esophageal high-resolution manometry, and esophagram (Figure 3)[23,57]. Each testing modality has a specific role in the diagnosis and evaluation of GERD, and no single test alone can provide the entire clinical picture[72].

Figure 3.

Patient diagnostics used in the evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms[23,61].

EGD

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)[73] and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)[57] recommend that EGD be performed for patients who have symptoms suggesting complicated GERD or alarm symptoms. Repeat EGD should also be performed in patients with severe erosive esophagitis after at least an 8-wk course of PPI therapy to exclude underlying Barrett’s esophagus and dysplasia[73,74].

pH monitoring

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring is critical to establish a diagnosis of GERD[75]. pH monitoring directly measures the extent and frequency with which acid refluxes into the esophagus and has been shown to be the most sensitive and specific test to objectively diagnose GERD[57,63]. pH-impedance monitoring also measures the proximal extent of reflux and can differentiate between acidic, weakly-acidic and non-acid reflux.

Manometry

In addition to upper endoscopy and esophageal pH testing, a preoperative evaluation should include high resolution manometry to ensure normal esophageal motility[19,57]. Manometry measures the pressure in the upper and lower esophageal sphincters, determines the effectiveness and coordination of peristalsis, and detects abnormal contractions. Manometry can be used to diagnose esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia, esophageal spasm, and lower esophageal sphincter hypotension and hypertension[57].

TYPICAL CLINICAL PATHWAYS FOR GERD SYMPTOMS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVING CARE WITH MSA

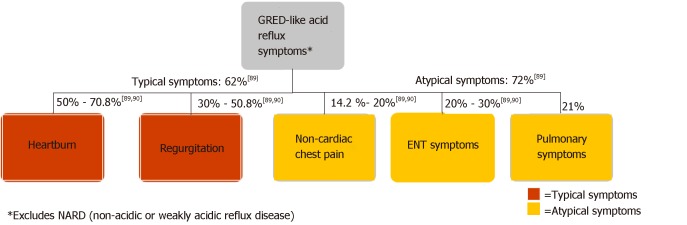

The diversity of clinical presentations of GERD poses challenges for clinicians in primary and specialty care settings. As Figure 4 illustrates, GERD patients may present with a range of typical or atypical symptoms. Typical symptoms of GERD include heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia[2,23,76,77]. Although dysphagia can be associated with uncomplicated GERD, its presence warrants investigation for alternative etiologies, including underlying motility disorder, stricture, ring, or neoplasm[23,78]. Atypical GERD symptoms may include dyspepsia, epigastric pain, nausea, bloating, and belching[19,23]. Extraesophageal GERD symptoms include chronic cough, chronic laryngitis, and associated asthma symptoms[23,77,79,80]. Atypical symptoms may overlap with other conditions, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Distinguishing them from GERD with appropriate diagnosis is important[81].

Figure 4.

Typical patient presentation in gastroesophageal reflux disease[89,90].

There is significant room for improvement in GERD diagnosis and treatment, particularly among patients with atypical symptoms for optimal patient care and healthcare resource utilization[81-83]. A study from AHRQ demonstrated that hospitalizations for disorders caused by GERD rose 103 percent between 1998 and 2005[84]. As such, detailed investigations and objective measurements in patients with symptoms of GERD should be performed with the intent of making the correct diagnosis, thus enabling choice of appropriate therapy[85].

Clinical pathways

In addition to obtaining an accurate diagnosis of GERD and conducting a through evaluation of the esophagus, it is also important that algorithms for referral for diagnosis to treatment be defined. When the diagnosis is uncertain or when GERD symptoms do not resolve following self-treatment, patients often present to primary care providers (PCPs)[81]. Some research has shown that patients with chronic diseases may have better health outcomes when PCPs co-manage care with specialists[86]. Patients with GERD also often present to emergency rooms (ERs). In an AHRQ analysis of GERD hospitalizations, 69% of patients initially presented to the ER[84]. Patients with GERD may also seek care from otolaryngologists, allergists, immunologists, and pulmonologists, as it is estimated that 38%-51% of asthmatics have GERD[79], and approximately 60% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea may have GERD[52]. In some cases, referrals to anti-reflux surgery may be limited to only those patients with severe disease and large hiatal hernias[87]. Timely referral of patients to a specialist in GERD when empiric treatment is insufficient may lead to improved clinical management[88]. However, referral algorithms across the spectrum of medical and surgical options are not established. Those data indicate that improved education and disease state awareness are critical for recognizing symptoms suggestive of GERD, and for navigating patients through appropriate diagnostic pathways to ensure timely specialty referral[86]. As such, establishing an easily understood, evidence-based algorithmic approach to implement best practices would serve better inform patients and physicians alike[89,90].

CONCLUSION

Optimal GERD management requires an emphasis on care coordination, improving healthcare quality through a patient-centered and evidence-based approach. An individualized approach to the GERD patient with a thorough understanding of optimal patient selection and patient referral to appropriate specialists is important for achieving desirable outcomes[15,49]. While lifestyle modi-fications and pharmacological therapy control symptoms for most GERD patients, there is a significant subset of patients whose symptoms are not adequately controlled. Objective testing is required to confirm the diagnosis, and to anatomically and physiologically evaluate the nature and severity of GERD and to help reveal the optimal patient treatment. For MSA surgery, the optimal population may be described and identified as a sub-segment of patient population who experience GERD symptoms of heartburn and/or uncontrolled regurgitation despite optimal medical management, have abnormal pH, and have normal esophageal motility.

Management algorithms incorporating medical and surgical treatments of GERD are not established. Currently, only a small fraction of eligible patients benefit from anti-reflux surgery. Reasons underlying the gap between potential surgical candidates and real-world utilization of anti-reflux surgery have not been well studied. Further studies are needed to identify impediments to access to surgical options for eligible patients. Strategies that may narrow this treatment gap include: (1) Improving PCP and gastroenterologist awareness of surgical guidelines; (2) Improving physician training curricula with respect to the evolving anti-reflux surgery procedures (such as MSA); and (3) Importantly developing an evidence-based, multidisciplinary referral network that includes the patient, the PCP, the gastroenterologist, and the surgeon. Such a network will empower both patients and providers access to all treatment options to optimally control their reflux disease, thereby potentially increasing the quality of life of patients and decreasing overall healthcare resource utilization.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: F Paul Buckley acts as an advisor to Ethicon and has received funding for surgeon teaching and consulting on product development; Benjamin Havemann has received funding from Ethicon as a guest speaker; Amarpreet Chawla is a paid full-time employee of Ethicon Inc. There was no funding for the design and development of this manuscript.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 22, 2019

First decision: May 9, 2019

Accepted: July 20, 2019

Article in press: July 20, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Caboclo JF, Fiori E, Harada H, Rawat KS, Sandhu DS, Vorobjova T S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor:A E-Editor: Zhou BX

Contributor Information

F Paul Buckley, Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, United States. tripp.buckley@austin.utexas.edu.

Benjamin Havemann, Austin Gastroenterology, Bee Cave, TX 78738, United States.

Amarpreet Chawla, Department of Health Economics and Market Access, Ethicon Inc. (Johnson and Johnson), Cincinnati, OH 45242, United States.

References

- 1.Menezes MA, Herbella FAM. Pathophysiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. World J Surg. 2017;41:1666–1671. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-3952-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefanidis D, Hope WW, Kohn GP, Reardon PR, Richardson WS, Fanelli RD SAGES Guidelines Committee. Guidelines for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2647–2669. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herregods TV, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: new understanding in a new era. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1202–1213. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikami DJ, Murayama KM. Physiology and pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95:515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patti MG. An Evidence-Based Approach to the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:73–78. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh SK, Kahrilas PJ, Brasseur JG. Liquid in the gastroesophageal segment promotes reflux, but compliance does not: a mathematical modeling study. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G920–G933. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90310.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyun JJ, Bak YT. Clinical significance of hiatal hernia. Gut Liver. 2011;5:267–277. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittal RK. The crural diaphragm, an external lower esophageal sphincter: a definitive study. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1565–1567. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90167-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandolfino JE, Kim H, Ghosh SK, Clarke JO, Zhang Q, Kahrilas PJ. High-resolution manometry of the EGJ: an analysis of crural diaphragm function in GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1056–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolone S, de Cassan C, de Bortoli N, Roman S, Galeazzi F, Salvador R, Marabotto E, Furnari M, Zentilin P, Marchi S, Bardini R, Sturniolo GC, Savarino V, Savarino E. Esophagogastric junction morphology is associated with a positive impedance-pH monitoring in patients with GERD. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1175–1182. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rona KA, Reynolds J, Schwameis K, Zehetner J, Samakar K, Oh P, Vong D, Sandhu K, Katkhouda N, Bildzukewicz N, Lipham JC. Efficacy of magnetic sphincter augmentation in patients with large hiatal hernias. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2096–2102. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandolfino JE, Zhang QG, Ghosh SK, Han A, Boniquit C, Kahrilas PJ. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux: mechanistic analysis using concurrent fluoroscopy and high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1725–1733. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halicka J, Banovcin P, Jr, Halickova M, Demeter M, Hyrdel R, Tatar M, Kollarik M. Acid infusion into the esophagus increases the number of meal-induced transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) in healthy volunteers. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1469–1476. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banovcin P, Jr, Halicka J, Halickova M, Duricek M, Hyrdel R, Tatar M, Kollarik M. Studies on the regulation of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) by acid in the esophagus and stomach. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:484–489. doi: 10.1111/dote.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz PO. Treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: use of algorithms to aid in management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:S3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(99)00656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) The IHI Triple Aim Initiative. 2019. [Accessed February 10, 2019] Available at: http://www.ihi.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, Powe NR. Referral of Patients to Specialists: Factors Affecting Choice of Specialist by Primary Care Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:245–252. doi: 10.1370/afm.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gikas A, Triantafillidis JK. The role of primary care physicians in early diagnosis and treatment of chronic gastrointestinal diseases. Int J Gen Med. 2014;7:159–173. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S58888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badillo R, Francis D. Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2014;5:105–112. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v5.i3.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yadlapati R, Dakhoul L, Pandolfino JE, Keswani RN. The Quality of Care for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:569–576. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vela MF, Camacho-Lobato L, Srinivasan R, Tutuian R, Katz PO, Castell DO. Simultaneous intraesophageal impedance and pH measurement of acid and nonacid gastroesophageal reflux: effect of omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1599–1606. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N. Response of regurgitation to proton pump inhibitor therapy in clinical trials of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1419–25; quiz 1426. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–28; quiz 329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minjarez R. Surgical therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. GI Motility online. 2006. p. 16 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore M, Afaneh C, Benhuri D, Antonacci C, Abelson J, Zarnegar R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: A review of surgical decision making. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:77–83. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter JE. Gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment: side effects and complications of fundoplication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:465–471; quiz e39. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganz RA. A Modern Magnetic Implant for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1326–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vakil N, Shaw M, Kirby R. Clinical effectiveness of laparoscopic fundoplication in a U.S. community. Am J Med. 2003;114:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellokumpu I, Voutilainen M, Haglund C, Färkkilä M, Roberts PJ, Kautiainen H. Quality of life following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: assessing short-term and long-term outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3810–3818. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i24.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganz RA, Edmundowicz SA, Taiganides PA, Lipham JC, Smith CD, DeVault KR, Horgan S, Jacobsen G, Luketich JD, Smith CC, Schlack-Haerer SC, Kothari SN, Dunst CM, Watson TJ, Peters J, Oelschlager BK, Perry KA, Melvin S, Bemelman WA, Smout AJ, Dunn D. Long-term Outcomes of Patients Receiving a Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation Device for Gastroesophageal Reflux. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:671–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipham JC, DeMeester TR, Ganz RA, Bonavina L, Saino G, Dunn DH, Fockens P, Bemelman W. The LINX® reflux management system: confirmed safety and efficacy now at 4 years. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2944–2949. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warren HF, Reynolds JL, Lipham JC, Zehetner J, Bildzukewicz NA, Taiganides PA, Mickley J, Aye RW, Farivar AS, Louie BE. Multi-institutional outcomes using magnetic sphincter augmentation versus Nissen fundoplication for chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3289–3296. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saino G, Bonavina L, Lipham JC, Dunn D, Ganz RA. Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation for Gastroesophageal Reflux at 5 Years: Final Results of a Pilot Study Show Long-Term Acid Reduction and Symptom Improvement. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:787–792. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith CD, DeVault KR, Buchanan M. Introduction of mechanical sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease into practice: early clinical outcomes and keys to successful adoption. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:776–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skubleny D, Switzer NJ, Dang J, Gill RS, Shi X, de Gara C, Birch DW, Wong C, Hutter MM, Karmali S. LINX® magnetic esophageal sphincter augmentation versus Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3078–3084. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds JL, Zehetner J, Nieh A, Bildzukewicz N, Sandhu K, Katkhouda N, Lipham JC. Charges, outcomes, and complications: a comparison of magnetic sphincter augmentation versus laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for the treatment of GERD. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3225–3230. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4635-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganz RA. The Esophageal Sphincter Device for Treatment of GERD. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2013;9:661–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prakash D, Campbell B, Wajed S. Introduction into the NHS of magnetic sphincter augmentation: an innovative surgical therapy for reflux - results and challenges. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100:251–256. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2017.0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aiolfi A, Asti E, Bernardi D, Bonitta G, Rausa E, Siboni S, Bonavina L. Early results of magnetic sphincter augmentation versus fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;52:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonavina L, Saino G, Bona D, Sironi A, Lazzari V. One hundred consecutive patients treated with magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease: 6 years of clinical experience from a single center. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonavina L, Saino G, Lipham JC, Demeester TR. LINX(®) Reflux Management System in chronic gastroesophageal reflux: a novel effective technology for restoring the natural barrier to reflux. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:261–268. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13486311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganz RA. A Review of New Surgical and Endoscopic Therapies for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2016;12:424–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bell R, Lipham J, Louie B, Williams V, Luketich J, Hill M, Richards W, Dunst C, Lister D, McDowell-Jacobs L, Reardon P, Woods K, Gould J, Buckley FP, 3rd, Kothari S, Khaitan L, Smith CD, Park A, Smith C, Jacobsen G, Abbas G, Katz P. Laparoscopic magnetic sphincter augmentation versus double-dose proton pump inhibitors for management of moderate-to-severe regurgitation in GERD: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:14–22.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riegler M, Schoppman SF, Bonavina L, Ashton D, Horbach T, Kemen M. Magnetic sphincter augmentation and fundoplication for GERD in clinical practice: one-year results of a multicenter, prospective observational study. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1123–1129. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warren HF, Louie BE, Farivar AS, Wilshire C, Aye RW. Manometric Changes to the Lower Esophageal Sphincter After Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation in Patients With Chronic Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Ann Surg. 2017;266:99–104. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Louie BE, Farivar AS, Shultz D, Brennan C, Vallières E, Aye RW. Short-term outcomes using magnetic sphincter augmentation versus Nissen fundoplication for medically resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:498–504; discussion 504-5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Louie BE, Smith CD, Smith CC, Bell RCW, Gillian GK, Mandel JS, Perry KA, Birkenhagen WK, Taiganides PA, Dunst CM, McCollister HM, Lipham JC, Khaitan LK, Tsuda ST, Jobe BA, Kothari SN, Gould JC. Objective Evidence of Reflux Control After Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation: One Year Results From a Post Approval Study. Ann Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen MY, Huang DY, Wu A, Zhu YB, Zhu HP, Lin LM, Cai XJ. Efficacy of Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation versus Nissen Fundoplication for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Short Term: A Meta-Analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:9596342. doi: 10.1155/2017/9596342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarani B, Scanlon J, Jackson P, Evans SR. Selection criteria among gastroenterologists and surgeons for laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s004640080169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:267–276. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimura Y, Kamiya T, Senoo K, Tsuchida K, Hirano A, Kojima H, Yamashita H, Yamakawa Y, Nishigaki N, Ozeki T, Endo M, Nakanishi K, Sando M, Inagaki Y, Shikano M, Mizoshita T, Kubota E, Tanida S, Kataoka H, Katsumi K, Joh T. Persistent reflux symptoms cause anxiety, depression, and mental health and sleep disorders in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2016;59:71–77. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.16-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung HK, Choung RS, Talley NJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep disorders: evidence for a causal link and therapeutic implications. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:22–29. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toghanian S, Johnson DA, Stålhammar NO, Zerbib F. Burden of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with persistent and intense symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor therapy: A post hoc analysis of the 2007 national health and wellness survey. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31:703–715. doi: 10.2165/11595480-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bashashati M, Hejazi RA, Andrews CN, Storr MA. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms not responding to proton pump inhibitor: GERD, NERD, NARD, esophageal hypersensitivity or dyspepsia? Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:335–341. doi: 10.1155/2014/904707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, Vakil NB, Johnson DA, Zuckerman S, Skammer W, Levine JG. Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:575–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gyawali CP, Fass R. Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:302–318. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, Hiltz SW, Black E, Modlin IM, Johnson SP, Allen J, Brill JV American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383–1391, 1391.e1-1391.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2018. National Guideline Clearinghouse. [Google Scholar]

- 59.University of Michigan Health System. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan Health System; 2012. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) p. Critical Care Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 60.2018. United States Census Bureau.U.S. and World Population Clock - Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G, Smout AJ. Management of the patient with incomplete response to PPI therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.El-Serag HB, Fitzgerald S, Richardson P. The extent and determinants of prescribing and adherence with acid-reducing medications: a national claims database study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2161–2167. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kleiman DA, Sporn MJ, Beninato T, Metz Y, Crawford C, Fahey TJ, 3rd, Zarnegar R. Early referral for 24-h esophageal pH monitoring may prevent unnecessary treatment with acid-reducing medications. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1302–1309. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2602-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kandulski A, Peitz U, Mönkemüller K, Neumann H, Weigt J, Malfertheiner P. GERD assessment including pH metry predicts a high response rate to PPI standard therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lacy BE, Chehade R, Crowell MD. A prospective study to compare a symptom-based reflux disease questionnaire to 48-h wireless pH monitoring for the identification of gastroesophageal reflux (revised 2-26-11) Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1604–1611. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kushnir VM, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Abnormal GERD parameters on ambulatory pH monitoring predict therapeutic success in noncardiac chest pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1032–1038. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Parameters on esophageal pH-impedance monitoring that predict outcomes of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:884–891. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dalton CB, Castell DO, Hewson EG, Wu WC, Richter JE. Diffuse esophageal spasm. A rare motility disorder not characterized by high-amplitude contractions. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1025–1028. doi: 10.1007/BF01297441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katz PO, Dalton CB, Richter JE, Wu WC, Castell DO. Esophageal testing of patients with noncardiac chest pain or dysphagia. Results of three years' experience with 1161 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:593–597. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-4-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Utilization Project (HCUP). 2014. Claims analysis - CPT code 43280; HCUP database analysis – ICD9 procedure code 44.67 . [Google Scholar]

- 71.Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) In: Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES), editor Technology and Value Assessment Committee (TAVAC); 2017. LINX® Reflux Management System. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jobe BA, Richter JE, Hoppo T, Peters JH, Bell R, Dengler WC, DeVault K, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Lacy BE, Pandolfino JE, Patti MG, Swanstrom LL, Kurian AA, Vela MF, Vaezi M, DeMeester TR. Preoperative diagnostic workup before antireflux surgery: an evidence and experience-based consensus of the Esophageal Diagnostic Advisory Panel. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:586–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Muthusamy VR, Lightdale JR, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Fonkalsrud L, Faulx AL, Khashab MA, Shaukat A, Wang A, Cash B, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in the management of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1305–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Naik RD, Vaezi MF. Recent advances in diagnostic testing for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:531–537. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1309286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richter JE, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF, Kahrilas PJ, Lacy BE, Ganz R, Dengler W, Oelschlager BK, Peters J, DeVault KR, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Conklin J, DeMeester T Esophageal Diagnostic Working Group. Utilization of wireless pH monitoring technologies: a summary of the proceedings from the esophageal diagnostic working group. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:755–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kahrilas PJ. Regurgitation in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9:37–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20; quiz 1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vakil NB, Traxler B, Levine D. Dysphagia in patients with erosive esophagitis: prevalence, severity, and response to proton pump inhibitor treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:665–668. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gaude GS. Pulmonary manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Thorac Med. 2009;4:115–123. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.53347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rao SS. Diagnosis and Management of Esophageal Chest Pain. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2011;7:50–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Player MS, Gill JM, Mainous AG, 3rd, Everett CJ, Koopman RJ, Diamond JJ, Lieberman MI, Chen YX. An electronic medical record-based intervention to improve quality of care for gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and atypical presentations of GERD. Qual Prim Care. 2010;18:223–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yadlapati R, Gawron AJ, Bilimoria K, Keswani RN, Dunbar KB, Kahrilas PJ, Katz P, Richter J, Schnoll-Sussman F, Soper N, Vela MF, Pandolfino JE. Development of quality measures for the care of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:874–883.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pandit S, Boktor M, Alexander JS, Becker F, Morris J. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: A clinical overview for primary care physicians. Pathophysiology. 2018;25:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhao Y, Encinosa W. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Hospitalizations in 1998 and 2005: Statistical Brief #44. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville MD. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nikaki K, Woodland P, Sifrim D. Adult and paediatric GERD: diagnosis, phenotypes and avoidance of excess treatments. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:529–542. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the Baton: Specialty Referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011;89:39–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rieder E, Riegler M, Simić AP, Skrobić OM, Bonavina L, Gurski R, Paireder M, Castell DO, Schoppmann SF. Alternative therapies for GERD: a way to personalized antireflux surgery. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1434:360–369. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Halpern R, Kothari S, Fuldeore M, Zarotsky V, Porter V, Dabbous O, Goldstein JL. GERD-Related Health Care Utilization, Therapy, and Reasons for Transfer of GERD Patients Between Primary Care Providers and Gastroenterologists in a US Managed Care Setting. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:328–337. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0927-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Karamanolis G, Vanuytsel T, Sifrim D, Bisschops R, Arts J, Caenepeel P, Dewulf D, Tack J. Yield of 24-hour esophageal pH and bilitec monitoring in patients with persisting symptoms on PPI therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2387–2393. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.de Miranda Gomes PR, Jr, Pereira da Rosa AR, Sakae T, Simic AP, Ricachenevsky Gurski R. Correlation between pathological distal esophageal acid exposure and ineffective esophageal motility. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2010;57:37–43. doi: 10.2298/aci1002037d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]