Abstract

Iroquois homeobox 1 (IRX1) belongs to the Iroquois homeobox family known to play an important role during embryonic development. Interestingly, however, recent studies have suggested that IRX1 also acts as a tumor suppressor. Here, we use homozygous knockout mutants of zebrafish to demonstrate that the IRX1 gene is a true tumor suppressor gene and mechanism of the tumor suppression is mediated by repressing cell cycle progression. In this study, we found that knockout of zebrafish Irx1 gene induced hyperplasia and tumorigenesis in the multiple organs where the gene was expressed. On the other hands, overexpression of the IRX1 gene in human tumor cell lines showed delayed cell proliferation of the tumor cells. These results suggest that the IRX1 gene is truly involved in tumor suppression. In an attempt to identify the genes regulated by the transcription factor IRX1, we performed microarray assay using the cRNA obtained from the knockout mutants. Our result indicated that the highest fold change of the differential genes fell into the gene category of cell cycle regulation, suggesting that the significant canonical pathway of IRX1 in antitumorigenesis is done by regulating cell cycle. Experiment with cell cycle blockers treated to IRX1 overexpressing tumor cells showed that the IRX1 overexpression actually delayed the cell cycle. Furthermore, Western blot analysis with cyclin antibodies showed that IRX1 overexpression induced decrease of cyclin production in the cancer cells. In conclusion, our in vivo and in vitro studies revealed that IRX1 gene functionally acts as a true tumor suppressor, inhibiting tumor cell growth by regulating cell cycle.

Abbreviations: IRX, Iroquois homeobox; TALEN, transcription activator-like effector nuclease; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

Introduction

Iroquois homeobox (IRX) is a member of transcription factor containing homeobox and plays an important role during embryonic development in both vertebrates and invertebrates [1]. The IRX gene was first discovered in Drosophila during mutagenesis screens [2], and later, the genes were also found in other animals being clustered into two groups, A (Irx1, Irx2, and Irx4) and B (Irx3, Irx5, and Irx6) [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Further studies have revealed that the genes are expressed in various organs including limb [10], gonad [11], kidney [12], heart [13], and lung [14].

Although the IRX gene family seems to play pivotal roles in patterning and cell specification during organ development in vertebrates, recent studies have suggested that the genes are also involved in tumor suppression [15], [16], [17], [18]. Several years ago, IRX1 gene was reported to suppress gastric carcinoma, demonstrating that the tumorigenicity was significantly reduced in nude mice subcutaneously inoculated with IRX1-transfected gastric cell lines [17]. Other study showed that IRX1 was found to be frequently methylated in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, suggesting silencing of the malignancy [18]. IRX2 and IRX3 gene were also suggested to be involved in suppressing carcinogenesis [19], [20].

Zebrafish model allows easy genetic modification at a lower cost, thus being a valuable model for cancer biology. Homozygous knockout strategy using the zebrafish model might provide valuable functional analysis of the gene. TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies have been well known for this purpose in animal models, and furthermore, zebrafish has also been demonstrated as a powerful animal model for phenotypic analysis of genes using the technologies [21]. Our group previously demonstrated that TALEN technology can be efficiently applied for functional analysis of genes in zebrafish model [22].

In zebrafish, Irx1 gene exists as a duplicated form, Irx1a and Irx1b. Thus, in this study, we used the two different knockout strategies to establish homozygous knockout mutants of the two zebrafish genes, and the homozygous knockout mutants showed aberrant phenotype of hyperplasia and tumor development in multiple organs where the genes are expressed. This result suggests that the zebrafish Irx1 gene is also involved in antitumorigenesis. Since the IRX1 is a transcription factor, we conducted microarray assay to identify the genes regulated by the IRX1, and the result suggested that the IRX1 functions in cell cycle regulation. Further analysis revealed that the antitumorigenicity was mediated by regulating cell cycle regulation especially at G2/M phase in bile duct cancer cells. This study provides understanding of IRX1 gene function and discusses potential mechanism of the gene in antitumorigenesis.

Material and Method

Mutagenesis of Irx1 in Zebrafish

Zebrafish homolog of Human IRX1 (Iroquois related homeobox 1) gene exists as a duplicated form of Irx1a (Gene bank: NC_007127.7; mRNA: NP_997067.1) and Irx1b (Gene bank: NC_007130.7; mRNA: NP_571898.1). For targeted mutation of these Irx1 genes in zebrafish, each gene was separately designed to induce frameshift mutation by using TALEN technology and CRISPR/Cas9 technology for Irx1a and Irx1b, respectively (Figure 1). The TALEN construct targeting the exon 1 of Irx1a gene was designed by using a software program (TAL Effector Nucleotide Targeter 2.0: TALEN Targeter) from the Bogdanove laboratory (https://boglab.plp.iastate.edu/node/add/talen). Based on the program, the TALEN sequences that recognize the exon 1 were found to be 5′-TCCCCCAGCTGGGCTACCCG- 3′ (left arm, RVD sequence: NG HD HD HD HD HD NI NH HD NG NH NH NH HD NG NI HD HD HD NH) and 5′-TCCCGGTCGGTCGCCTCCG-3′ (right arm, RVD sequence: NG HD HD HD NH NH NG HD NH NH NG HD NH HD HD NG HD HD NH) (Figure 1A). Spacer sequence which is flanked by the two TALENs was 5′-CAGTATTTAAGTGCCTCCCAGGCGGTGTAA-3′. Both TALEN constructs were generated by using TALEN Toolbox kit (Addgene), following the protocol provided by Feng Zhang laboratory (reference nature protocol). After the sequence verification, capped mRNA was produced by in vitro transcription of the plasmid (mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 ULTRA kit (Ambion Co.)) individually consisting of left or right arm sequences.

Figure 1.

Generation of Irx1 knock-out zebrafish. Targeted gene mutation was performed by TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 knockout methods for Irx1a (A) and for Irx1b gene (B), respectively. Frameshift mutation was caused by the knockout strategies. Insertion or deletion of the nucleotides was indicated by red letterings. (C) Three-day-old embryos of the zebrafish mutants. While either Irx1a or Irx1b homozygote mutants did not show abnormal morphology during embryonic development, some siblings (homozygote for both Irx1a and Irx1b) from the breeding of Irx1a−/−/1b+/− and Irx1a+/−/1b−/− showed severe morphologic abnormality. This suggests that majority of homozygote mutants of Irx1a and Irx1b are developmentally defective. A few of Irx1a−/−/1b−/− zebrafish, however, were found to survive up to 3 months of age but were not fertile and died within 6 months of age.

CRISPR/Cas9 technology was applied for Irx1b knockout mutation by using pT7gRNA (Addgene) and pRGEN-Cas9-CMV (Toolgen). The target site was identified from E-crisp (www.e-crisp.org) online site, finding that the target sequence of guide RNA was 5′-CCAAGAGCGCTACCAGAGAAA-3′, which presents on exon 2 of zebrafish Irx1b gene (Figure 1B). The construct was then generated by following the protocol provided by Chen laboratory. After sequence verification, pT7-gRNA construct carrying guide RNA was linearized with BamHI, and capped mRNA was generated by in vitro transcription using MEGAshortscript T7 kit (Ambion Co). Cas9 mRNA was generated by using pRGEN-Cas9-CMV.

Establishment of Irx1-Null Zebrafish Mutants

DNA break at the identified targeted site was induced by injecting the capped mRNA into the yolk of AB zebrafish embryos using an MMPI-2 microinjector at single cell stage. In order to make the DNA break of Irx1a, injection mixture was prepared by reconstituting the left and right arm mRNAs (final concentration of each mRNA, 30 ng/ml) in Danieu's buffer mixed with 0.03% phenol red, and injection mixture for targeting Irx1b was prepared by reconstituting 50 ng/μl of Cas9 mRNA and 150 ng/μl of gRNA in 20 mM Hepes and 150 mM KCl buffer mixed with 0.03% phenol red. Each injection mixture was then introduced into the one-cell AB zebrafish embryos and raised till adulthood. The F1 progenies were obtained by backcrossing the F0 adult zebrafish to AB wild-type zebrafish.

For screening of the germline mutation, the F1 progenies were individually verified by sequence analysis of the PCR products amplified from the genomic DNA isolated by tail fin clipping method. Primer sequences used to amplify the exon1 sequences of Irx1a were 5′-ACATCAGTTGGAGCTCAATT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGGAGAAAAGAGCCAGATC-3′ (reverse), and the exon2 sequences of Irx1b were 5′-GGTCGCAGTATGAGCTGAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTCTCCTTTTTGAGTCTCCG-3′ (reverse). The identified heterozygous mutant zebrafish were backcrossed again with the AB zebrafish to produce F2 progenies. The homozygous Irx1a-null and Irx1b-null zebrafish were then obtained from the F3 progenies produced by inbreeding of the F2 heterozygote progenies (Figure 1).

Animal Stocks and Embryo Care

Wile-type (AB), Irx1a−/−, and Irx1b−/− zebrafish were raised in a standardized aquaria system (Genomic-Design Co., Daejeon, Korea) (http://zebrafish.co.kr). The system provides continuous water flow, biofiltration tank, constant temperature maintenance at 28.5°C, UV sterilization, and 14-hour light and 10-hour dark cycle. We strictly followed the Guidelines for the Welfare and Use of Animals in Cancer Research [23].

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the visceral organs of 3-month-old zebrafish of AB, Irx1a−/− and Irx1a−/−/b−/− using RNeasy Miniprep kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The RNA purity and integrity were evaluated by ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, USA). Microarray procedures were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, RNA was labeled and hybridized with Cy3-dCTP, following the Agilent One-Color Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis protocol (Agilent Technology, V 6.5, 2010). The labeled cRNAs were then purified by RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and measured by NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, USA). Labeled cRNA was fragmented and hybridized to the Agilent SurePrint HD Zebrafish v3 GE 4X44K Microarrays (Agilent). Microarrays were incubated for 17 hours at 65°C in an Agilent hybridization oven and washed at room temperature according to the Agilent One-Color Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis protocol (Agilent Technology, V 6.5, 2010). The hybridized array was immediately scanned with an Agilent Microarray Scanner D (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), and expression data were generated using Agilent Feature Extraction software v11.0 (Agilent Technologies). Gene-Enrichment and Functional Annotation analysis for significant probe list was performed using Gene Ontology (www.geneontology.org/). All data analyses and visualization of differentially expressed genes were conducted by using R 3.1.2 (www.r-project.org). Hierarchical clustering analysis based on Euclidean distance, and average linkage was performed using TMEV software [24].

Real-Time PCR and Western Blot Analyses

Real-time PCR was performed by using the whole zebrafish embryos and 3-month-old zebrafish liver and intestine. RNA was extracted by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of the total RNA with a Maxima First Stand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, K1641, Glen Burnic, MD). The real-time PCR was conducted by using Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, K0222) on a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster city CA). The primer sequences for Real-time PCR are shown in Supplementary Table1.

For Western blot analyses, whole cell protein extracts were prepared with a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCL (pH 7.9), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2% SDS, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1 M and protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo scientific)). After treating 20 μg of the total protein with Laemmli sample buffer and heating at 100°C for 5 minutes, the total proteins were resolved by 8% and 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The electroblotted nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare life Sciences) containing the proteins was blocked in a solution with 5% nonfat dry milk and PBS-T. Antibodies used for Western blot analyses were rabbit anti–cyclin D1 (1:1000, Abcam, EPR2241), rabbit anti–cyclin E1 (1:1000, Abcam, EP435E), mouse anti–cyclin B1 (1:1000, Santacruz, GNS1), mouse anti–cyclin A (1:1000, Santacruz, B-8), anti–human IRX1 (1:500, Abcam, ab66310), mouse anti-turboGFP (1:1000, Origene, TA150041), and β-actin (1:2000, Cell signaling, #4967 L). Visualization of the protein band was done with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000, Gendepot, USA), and the band density was measured by using TINA image software (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and In Situ Hybridization

Histologic evaluation was done by using 4-μm sections of paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue. Hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining was performed according to standard protocols. IHC and ISH experiments were carried out as previously described [22], [25]. Primary antibodies used for IHC were mouse anti–proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, 1:2000), mouse anti–-cytokeratin 19 (CK19, 1:500), and mouse anti-pancytokeratin (1:500) purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). For ISH, riboprobes were generated by PCR amplification with partial cDNA using appropriate primers. Primer sequences used for PCR were 5′-ATGTCTTTCCCCCAGCTGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCCAGATCTATCTCCTCTTCG-3′ (reverse) for Irx1a (product size 633 bp), and 5′-ATGTCGTTCCCCCAACTGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCATATCGATGGTCTCCAGATC-3′ (reverse) for Irx1b (product size 658 bp). The underlined sequences are T7 RNA polymerase-binding sites. In vitro transcription was carried out using mMEssage mMACHINE T7 ultra Kit (Ambion). Hybridization was done at 60°C for overnight, and serial stringent wash was done at 68°C. Hybridized riboprobe was detected by anti-dig antibody binding and detected by NBT/BCIP AP substrate solution (Roche). The slides were counterstained with neutral red.

Overexpression of IRX1 Gene in Human Cancer Cells and Cell Cycle Analysis

IRX1 gene overexpression was made to the human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines HuCCT1 and SNU1196. These cells were lentivirally transformed with the human IRX1 gene fused with IRX1-GFP (pLentiCMV:Irx1-GFP, Origene, RG218767) or GFP (pLentiCMV:GFP, Origene, PS100019) alone as a control. After the lentiviral transduction, GFP-positive cells were selected by using BD Aria III FACS (Becton Dickinson Co.). Phenotypic changes in the cell proliferation and apoptosis were then evaluated.

For cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry, the transduced cholangiocarcinoma cells were fixed with ethanol, labeled with mitotic marker (Alexa588-conjugated anti–phosphohistone H3, Cell Signaling 3458S), and stained with propidium iodide. To evaluate the cell cycle progression, the transduced cells were synchronized at either G1/S phase or G2/M phase by treating with hydroxyurea (1 mM, Sigma H8627) or nocodazole (100 ng/mL, Sigma, M1404), respectively. After 16 hours of cell cycle arrest, the synchronized cells were released from the cell cycle arrest, harvested at indicated time point, and then processed to flow cytometry experiment. Annexin V antibody (Santacruz, sc-74,438) was used to perform apoptotic analysis.

Results

Targeted Knockout and Expression of Irx1 Gene in Zebrafish

In order to obtain knockout mutants of target genes, each gene was separately designed to induce frameshift mutation by using TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies for Irx1a and Irx1b, respectively (Figure 1). DNA break at the identified targeted site was induced by injecting the capped mRNA into the yolk of AB zebrafish embryos (See Materials and Method). Genomic DNA sequencing of the progenies from F0 founder zebrafish revealed that single nucleotide C insertion and two nucleotides (CG) deletion with three nucleotides insertion (TTT) occurred, respectively, in the Irx1a and Irx1b regions, resulting in frameshift mutation (Figure 1, A and B). Homozygous mutants of Irx1a and Irx1b were then successfully generated (Figure 1C). The homozygous mutants for Irx1a (Irx1a−/−) and Irx1b (Irx1b−/−) were vital without showing morphological abnormality at embryogenic stage and survived long enough to cause abnormal phenotypes later. However, homozygous mutants for both Irx1a and Irx1b (Irx1a−/−/b−/−) were severely malformed (Figure 1C). Only few of them survived till 3 months of age (all died within 6 months) and were not fertile, reflecting the lethal phenotype found in other mammal study.

We also performed expression analysis of the Irx1 gene in zebrafish (Figure 2). In humans, the IRX1 gene is expressed in multiple organs including lung, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, brain, and also in reproductive organ [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Similarly, our whole mount ISH experiment showed that zebrafish embryo also expressed the gene in the various organs (Figure 2A). ISH experiment with different organ tissue sections further revealed the detailed expression patterns in those organs (Figure 2, B and C). Meticulous examination of the ISH slides under a microscope showed that the gene was also expressed in both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, which was not previously documented (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Expression of zebrafish Irx1 gene. (A) Whole mount ISH expression in embryogenic zebrafish. Irx1 gene expression is found highly in brain area at early developmental stage (see 48 hpf, hours postfertilizaton) and later distributed to internal organs (5 dpf, days postfertilization). (B-D) Images of ISH in 3-month-old adult tissue sections. (B) Expression in intestine and kidney. Both Irx1a and Irx1b genes are expressed at the crypt base of intestines and renal tubular cells. (C) ISH observation of Irx1 gene expression in reproductive organs, typically in primordial germ cells and oocytes (insets indicate 40× low-power images). (D) Expression in the liver and bile ducts. While none of the hepatocytes express Irx1 gene, meticulous examination revealed obvious expression in the biliary tree including extrahepatic (arrows) and intrahepatic bile ducts (arrowheads).

Tumorigenesis Occurs in Multiple Organs of the Irx1 Gene Knockout Zebrafish

Observation of the abnormal phenotypes caused by the Irx1 gene knockout was done with the homozygous Irx1a-null and Irx1b-null zebrafish. In order to do this, serial analysis of histology was carried out with the tissue sections from 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month-old knockout zebrafish (Figures 3 and 4). The result showed that hyperplasia and/or tumor developed in the multiple organs where we observed the Irx1 gene expression, suggesting that the gene knockout was successfully made to the targeted organs and that the Irx1 gene was involved in tumor suppression in zebrafish (Figure 3). During our observation of the tumor formation among the different organs, we found that the hyperplasia and tumorigenesis occurred more frequently in bile duct organ than occurred in any other organs (Figure 4, Table 1). Biliary hyperplasia occurred as early as 3 months old in the knockout zebrafish, and the bile duct tumors showed occasionally invasive growth into the liver (Figure 4C), pancreas (Figure 4, D and G), and intestine (Figure 4E). ISH for Irx1 revealed rather strong expression of both Irx1a and Irx1b mRNA (although the mRNA harbors mutations) in the tumor cells (Figure 4, O and P). This seemed to be caused by loss of feedback mechanism of transcriptional inhibition due to lack of functioning Irx1 protein. As the normal bile duct cells express Irx1 mRNAs (Figure 2D), the positivity on ISH is supportive finding that the tumors are originated from bile duct cells. Interestingly, although the abnormal phenotypes were observed basically to be identical in both Irx1a and Irx1b knockout mutants, we found that the abnormal phenotypes were prominently induced by Irx1a gene knockout than induced by Irx1b gene knockout (Table 1). This suggests that functional preservation of the gene relies more on Irx1a gene. During investigation of other organs, organomegaly by hyperplasia was a prominent feature with occasional tumor formation in testis, ovary, and kidney. Taken together, the results suggest that the gene acts as antitumorigenesis in zebrafish.

Figure 3.

Abnormal phenotypes developed in multiple organs caused by Irx1 knockout in zebrafish (long-term observation up to 18 months). (A, B, and E) Control. (C and D, F-L) Irx1a knockout (Irx1b data not shown due to similar images). Hyperplasia or tumor developed in the multiple organs where certain degree of Irx1 expression was noted on the ISH experiment. Note the testicular (black arrowheads), renal (red arrowheads), and ovarian tumors (arrow). (L) Cystic tumor of ovary (Inset indicates IHC image of CK19).

Figure 4.

Bile duct phenotypes and tumor invasions found in the Irx1a knockout (Irx1b data not shown due to similar images). (A and B) A large liver mass (boundary by red arrowheads) showing positivity for PCNA. The tumors often invaded the liver (C and K), intestine (E), and pancreas (D, G, and L). The bile duct tumor was often multifocal (H and I) (black arrowheads). (M) Tumor cells revealed robust expression of PCNA suggesting enhanced proliferation. (N) IHC for pancytokeratin in tumor cells. (O and P) ISH images for Irx1 mRNA showing positive expression of both Irx1a and Irx1b genes in the tumor cells. As the bile duct cells in the knockout lines also produce Irx1 mRNAs that harbor mutations, the positivity on ISH is supportive finding that the tumors are originated from bile duct cells. P, pancreas; L, liver.

Table 1.

Phenotypic Changes Induced by Irx1 Gene Knockout

| 6 Months |

12 Months |

18 Months |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irx1a −/− | Irx1b −/− | Irx1a −/− | Irx1b −/− | Irx1a −/− | Irx1b −/− | |

| Intestinal hyperplasia | 8.3% (2/24) | 4.2% (1/24) | 37.5% (9/24) | 25.0% (6/24) | 54.2% (13/24) | 33.3% (8/24) |

| Testicular hyperplasia | 0% (0/13) | 0% (0/12) | 25.0% (3/12) | 8.3% (1/12) | 54.5% (6/11) | 18.2% (6/11) |

| Testicular tumor | 0% (0/13) | 0% (0/12) | 8.3% (1/12) | 0% (0/12) | 9.1% (1/11) | 0% (0/11) |

| Ovarian hyperplasia | 0% (0/11) | 0% (0/12) | 8.3% (1/12) | 8.3% (1/12) | 30.8% (4/13) | 15.4% (2/13) |

| Ovarian tumor | 0% (0/11) | 0% (0/12) | 8.3% (1/12) | 0% (0/12) | 7.7% (1/13) | 7.7% (1/13) |

| Renal hyperplasia | 8.3% (2/24) | 4.2% (1/24) | 20.8% (5/24) | 12.5% (3/24) | 37.5% (9/24) | 16.7% (4/24) |

| Renal tumor | 0% (0/24) | 0% (0/24) | 0% (0/24) | 0% (0/24) | 4.2% (1/24) | 0% (0/24) |

| Bile duct hyperplasia | 50.0% (12/24) | 25.0% (6/24) | 70.8% (17/24) | 37.5% (9/24) | 87.5% (21/24) | 66.7% (16/24) |

| Bile duct tumor | 25.0% (6/24) | 4.2% (1/24) | 45.8% (11/24) | 12.5% (3/24) | 66.7% (16/24) | 50.0% (12/24) |

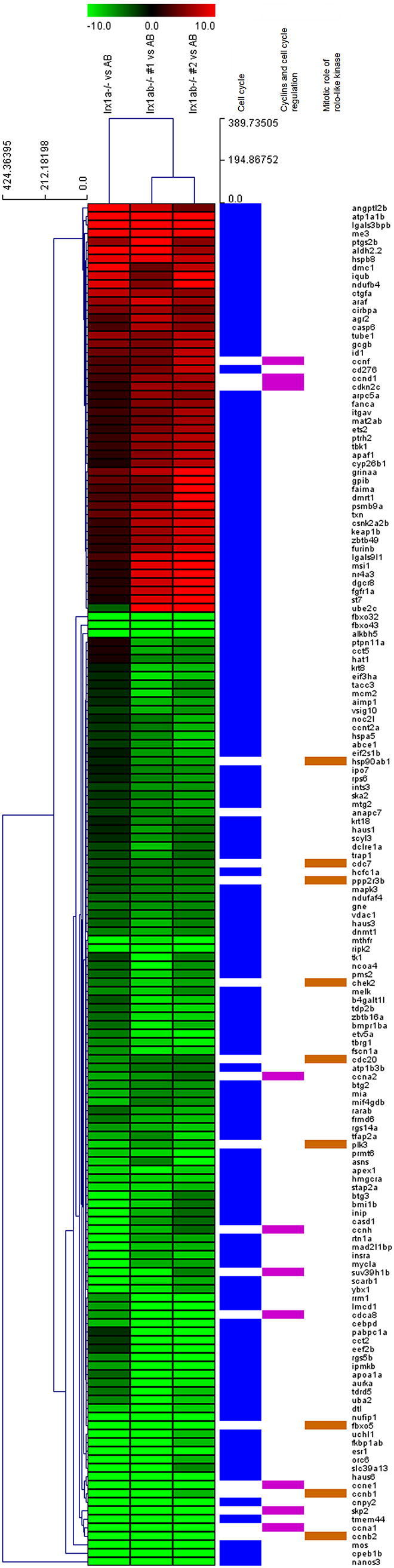

Differential Gene Expression Induced by Irx1 in Zebrafish

We further characterized the relevant phenotypes and possible mechanism of the antitumorigenesis driven by the Irx1. To do this, we performed microarray (Agilent Gene Chip) analysis using the cRNA from the visceral organs of 3-month-old zebrafish (Figure 5): Experimental samples were one pooled AB control, two pooled Irx1a−/−, and two separately prepared Irx1a−/−/b−/− zebrafish RNAs. Because majority of the homozygote mutants of both Irx1 genes did not survive, repetitive genotyping was required to find Irx1a−/−/b−/−. The result indicated that among the 80 adult zebrafish bred from the crossing of Irx1a+/−/b−/− and Irx1a−/−/b+/, only four of them were found to be Irx1a−/−/b−/−. Based on the microarray analysis, we were able to find 687 upregulated and 963 downregulated genes in the knockout mutant (Figure 5, A and B, refer to Supplementary Fig. 1 for high-resolution image). Of them, five top canonical pathways changed by Irx1 knockout were found to include cyclins and cell cycle regulation, mitotic roles of polo-like kinase, farnesoid X / retinoid X receptor (FXR/RXR) activation, estrogen-mediated S-phase entry, and cell cycle control of chromosomal replication (Supplementary Table 2). Further categorizing them into detailed manner according to Gene Ontology (GO) terms, we found that the largest number of the differential genes was involved in cell cycle (165 genes for cyclins and cell cycle regulation, mitotic roles of polo-like kinase, and cell cycle; 137 genes for cell death and survival; 115 for cell growth and proliferation; and 101 for cancer pathways). The result suggests that cell cycle pathways are possibly regulated by IRX1 (list of differential genes relevant to cell cycle is shown in Supplementary Table 3). To further confirm this, real-time RT-PCR was performed against the genes related to cell cycle regulation, and we found that the results were largely correlated with the microarray data (Figure 5C, refer to Supplementary Table 1 for primer sequences). Taken together, our result suggests that the significant canonical pathway of IRX1 in achieving antitumorigenesis is done by regulating cell cycle.

Figure 5.

cRNA microarray analysis. (A and B) Differential genes were explored by microarray (Agilent Gene Chip) analysis using the visceral organs of 3-month-old zebrafish from AB, Irx1a−/−, and Irx1a−/−/b−/−. The microarray revealed 687 upregulated and 963 downregulated genes by Irx1a/b knockout. Significant canonical pathways were cyclins and cell cycle regulation, mitotic roles of polo-like kinase, FXR/RXR activation, estrogen-mediated S-phase entry, and cell cycle control of chromosomal replication. The upper colored bar indicates the gene expression, and the metric used was Euclidean distance, with average linkage for distance between clusters. (C) Real-time RT-PCR recapitulated the microarray results.

Supplementary Fig. 1.

cRNA microarray analysis. High-resolution image of Figure 5A.

Overexpression of IRX1 Gene Inhibits Proliferation of Human Cholangiocarcinoma Cells

As the tumorigenesis in bile duct was found to be the predominant phenotype in the Irx1 knockout zebrafish (Figure 4), we decided to further evaluate the role of Irx1 by performing transduction of human IRX1 gene into cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. To do this, two different cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, HuCCT1 and SNU1196, respectively, containing high and low IRX1 gene expression, were chosen for the transduction study. In this way, we expected that phenotypic changes induced by IRX1 gene overexpression would be more evidently appeared on SNU1196, the low IRX1 gene expressing cell line, than appeared on the high IRX1 gene expressing cell line HuCCT1. GFP gene was fused to the IRX1 gene to enable observation of the transgene expression (Figure 6, A and C). The result showed that overexpression of the IRX1 gene resulted in decreased cell proliferation of both HuCCT1 and SNU1196, supporting our finding that the gene is involved in antitumorigenesis (Figure 6D). Upon treatment with H2O2 to the cell lines, the SNU1196 cells (the low Irx1 expressing cell) were found to be more sensitive to oxidative stress, showing much more increased fraction of Annexin V–positive (apoptotic) or propidium iodide–positive (dead) cells in flow cytometry analysis (Figure 6E). The result suggested that IRX1 gene expression inhibited cell proliferation and sensitized cells to apoptotic stimuli. Furthermore, our flow cytometry experiment using pHH3, a specific marker for mitosis, to examine the alteration of cell cycle showed that IRX1 gene overexpression induced decrease of the mitotic cell fraction in both HuCCT1 and SNU1196 (Figure 6F), suggesting that Irx1 is associated with the cell cycle regulation.

Figure 6.

Transduction of human IRX1 gene into human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. (A) Western blot experiment showed Irx1 expression in four different cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. Among these, HuCCT1 (high Irx1 expression cell line) and SNU1196 (low Irx1 expression cell line) were selected for overexpression study. (B) Lentiviral transduction of IRX1-GFP fusion gene (right). Note the nuclear localization of IRX1-GFP in Irx1 transduced cells whereas GFP-alone transduced cell showed diffused expression (left). (C) Western blot experiment confirmed the transduced protein, tGFP. Fused IRX1-tGFP protein bands are seen with larger size. (D) Cell proliferation assay. The results showed that IRX1 overexpression resulted in decreased cellular proliferation in both HuCCT1 and SNU1196 cell lines. (E) Flow cytometry analysis for cell death induced by H2O2 treatment showing increased susceptibility to H2O2 in the Irx1-expressing cells. (F) Flow cytometry for cell cycle change. IRX1-expressing cells showed decreased mitotic fraction measured by phosphohistone H3 (pHH3).

Prominent Delay in Mitotic Progression of the IRX1 Overexpressed Cholangiocarcinoma Cells

To further confirm that the IRX1 is responsible for tumor suppression by regulating cell cycle, the cholangiocarcinoma cells were synchronized by treating the two different cell cycle blockers, hydroxyuria and nocodazole, which block G1/S phase and G2/M phase, respectively. The cells were then released and monitored for exit from their arrested phases to find that IRX1 overexpression actually delays the cell cycle. On flow cytometry analyses of the released cells from their arrested point (i.e., 0 hour in the Figure 7, A and B), the results showed that IRX1 expression actually delayed each progression of the cell cycle in the two different cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. The cell cycle delay was profoundly affected at mitotic exit especially in SNU1196, the low IRX1 expressing cell, as expected. Confirmation of our observation was also done by pHH3 staining of the released cells from nocodazole-induced M phase arrest. The result showed that IRX1 overexpressing cells revealed higher fraction of pHH3-positive cells at 3 and 6 hours after release, indicating that delayed mitotic exit and reentry into G1 occurred in the transduced cells (Figure 7C). Western blot experiments also detected decreased amounts of active cyclins involved in cell cycle progression in those cells compared to the control (Figure 7D). Taken together, the results suggested that tumor suppression of the gene is mediated by repressing cell cycle progression.

Figure 7.

Cell cycle synchronization study. (A and B) Cell synchronization was obtained by treatment with hydroxyuria and nocodazole, respectively, for G1/S and G2/M phase arrest. Arrest was then released, detecting the cell cycle progression. Dotted red lines indicate 2N and 4N cells. The result showed that mitotic exit is markedly delayed by IRX1 overexpression, while S phase progression is slightly delayed. Numbers in upper and lower lines indicate G1/S and G2/M fractions, respectively. (C) The mitosis marked by pHH3. G2/M phase-blocked cells were released and stained for pHH3 at indicated time points. Yellow to white cells (red arrowheads) represent pHH3- and GFP-positive cells. Numbers of percentage indicate fractions of the pHH3-positive cells. At 3 and 6 hours after release, higher cell fractions are still positive for pHH3 in IRX1-expressing cells. (D) Western blot analysis against cyclins. The result showed that levels of various cyclin expression are decreased by IRX1 expression.

Discussion

IRX gene family encodes homeobox-containing transcription factors. In mammalian, the genes are known to be clustered on two genomes that consist of a total of six IRX genes, and the genes play important roles in pattern formation during embryonic development [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. All IRX genes are found to be expressed either specifically or redundantly in different organs. Among the IRX genes, recent studies showed that IRX1 gene functions as a tumor suppressor [17]. Not only for the tumor suppressor, IRX1 also acts an oncogene, especially when the gene undergoes allelic deletion or promoter methylation. For instance, in osteosarcoma, IRX1 was identified as a metastatic oncogene that is activated by hypomethylation [26], whereas the gene was reported as a tumor suppressor in other cancer types [14], [15], [18]. Although those reports suggest that IRX genes are involved in regulation of tumor development, understanding of the mechanism in tumorigenesis is very limited at current.

In zebrafish, Irx1 gene exists as a duplicated form, as Irx1a and Irx1b genes. Identification and expression of the Irx1 gene in this animal were first reported in 2001, but functional role of the gene was unclear [27]. In fact, none of studies have revealed yet how the gene is involved in antitumorigenesis. In this study of functional analysis of Irx1 gene, we generated each of homozygous Irx1a and Irx1b mutants that were vital and fertile to generate descendants (Figure 1). To do this, we used two different knockout strategies, TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9. At the beginning of this study, TALEN technology was more accessible for us to generate knockout mutant, successfully targeting Irx1a gene. This technology was however complicated and inconvenient especially when generating constructs for knockout. Thus, later, we used CRISPR/Cas9 technology for targeting Irx1b gene. Homozygous Irx1a-null and Irx1b-null zebrafish were then obtained from the F3 progenies produced by inbreeding of the F2 heterozygote progenies (Figure 1C).

Our investigation of the Irx1 gene expression showed that the gene is expressed in various internal organs of zebrafish as similarly displayed in other animals, including humans (Figure 2). Meticulous expression study using ISH experiment included a prominent expression of Irx1 gene also in bile duct which has never been documented so far (Figure 2D). Observation of abnormal phenotypes caused by the gene knockout in the zebrafish mutants revealed that the mutants contained tumor development where the gene was expressed (Figure 3). This suggests that the Irx1 gene is involved in antitumorigenesis in multiple organs. In mammals, Irx genes often showed overlapping patterns of expression, suggesting their redundant roles in development [10]. From our investigation, we also found that expression pattern of the two Irx1 genes was tissue and organ specific but was redundant (Figure 2). The same redundancy was phenotypically observed from both Irx1a and Irx1b knockout mutants, although the abnormal phenotype was found to be more prominent in the Irx1a mutant than appeared on Irx1b mutants. The results suggested that the two genes were functionally overlapped and that the functional preservation may dominantly rely on Irx1a gene. Unlike in other mammalian studies with homozygous mutants, we believe that because of this functional redundancy, the zebrafish homozygous mutants were able to survive long enough to show the phenotypic abnormality of tumorigenesis in the multiple organs, although the Irx1a/b knockout mutants did not survive longer than 6 months. Taken together, our observations revealed that Irx1 gene functioned to suppress tumorigenesis in zebrafish at multiple locations where the gene was expressed.

Further study with the zebrafish mutants was focused on characterization of the gene behavior during the tumor development especially in bile duct since the tumorigenicity in the particular organ occurred more frequently than occurred in any other organs and the bile duct tumor was often invasive to near organs, liver and pancreas (Figure 4). Histological analysis with the serial sections obtained from the internal organs well revealed how the tumor masses were severely formed in the organs of the knockout mutants (Figure 3). This finding also referred to our expression analysis, showing that the Irx1 gene was expressed in both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct, whereas the gene was not expressed in hepatocytes (Figure 2D). This suggests that the gene may contain important roles in the development of cholangiocarcinoma previously not known. As the tumorigenicity in bile duct was found to be the predominant phenotype in these Irx1 knockout zebrafish, we considered that study with overexpression of IRX1 gene in human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines was useful to confirm the IRX1 role in antitumorigenesis. In vitro assay using the cholangiocarcinoma cell lines showed that overexpression of the IRX1 gene resulted in decreased cell proliferation and increased susceptibility to H2O2-induced oxidative stress, supporting our finding that the gene is involved in antitumorigenesis (Figure 6). Taken together, these results indicate that IRX1 gene is a true tumor suppressor.

In an attempt of identifying the genes regulated by the transcription factor Irx1 during antitumorigenesis, we performed cRNA microarray assay using the cRNA obtained from the knockout mutants (Figure 5). This microarray analysis allowed us to understand changes of the downstream gene expression of Irx1. After investigating 687 upregulated and 963 downregulated genes identified from the microarray, our result showed that the significant fold change of the genes fell into the category of the genes involved in cell cycle regulation. Especially, we noticed that the highest fold change occurred in CDKN2ab (homolog for CDKN2A in mammals), a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, which codes for two proteins: p16INK4a and p14arf [28], [29]. These two proteins are known to act as tumor suppressor by regulating the cell cycle. The result suggests that the significant canonical pathway of IRX1 in antitumorigenesis is possibly done by regulating cell cycle. In a previous study with gastric cancer, protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5, an enzyme responsible for symmetric demethylation of histone) has been introduced as an upstream regulator of IRX1, suggesting that methylation of the gene is involved in tumorigenic process [15]. Further study with PRMT5 has revealed that knockout of IRX1 gene induces cell cycle arrest and growth inhibition [30]. Also, a study with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma has suggested that methylation of IRX1 gene induces tumorigenesis by causing decrease of the gene expression [18]. On the other hand, overexpression of the IRX1 gene in this cancer cell has showed suppression of the cell growth and colony formation. Taken together, these results suggest that the IRX1 gene expression is suppressed by hypermethylation during tumorigenesis and that restoring the gene expression inhibits tumorigenesis in cancer cells. In our study with the cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, IRX1 overexpression also resulted in delayed progression of the tumor cell cycle along with decrease of cyclin expression, and the most prominent changes were delayed mitotic exit and reentry into G1 phase (Figure 7). Although it necessitates to further clarify how IRX1 controls the progression of mitotic phase, these results indicate that regulation of cell cycle is an important mechanism of IRX1 function leading to tumor suppression.

In this study with homozygous knockout mutants of Irx1 in zebrafish, the results have demonstrated that the gene functions as a true tumor suppressor. Our molecular study provides further understanding of IRX1 gene function, revealing that tumor suppression is mediated by repressing cell cycle progression. This study also suggests potential roles of the gene in bile duct organ previously undescribed. At the present study, however, we do not understand how IRX1, as a transcription factor, regulates cyclin production during cell cycle progression. Further molecular analysis is needed to unveil the mechanism and the functional roles of IRX1 in antitumorigenesis including cholangiocarcinoma.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Supplementary tables

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (1345269929); Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute of Korea (H14C1324); National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (1711053448).

Contributor Information

In Hye Jung, Email: iherb21@yuhs.ac.

Dawoon E. Jung, Email: estherjung@yuhs.ac.

Yong-Yoon Chung, Email: ychung@smtbio.co.kr.

Kyung-Sik Kim, Email: kskim88@yuhs.ac.

Seung Woo Park, Email: swoopark@yuhs.ac.

References

- 1.Cavodeassi F, Modolell J, Gomez-Skarmeta JL. The Iroquois family of genes: from body building to neural patterning. Development. 2001;128(15):2847–2855. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.15.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez-Skarmeta JL, D ´ıez-del-Corral R, de la Calle-Mustienes E, Ferre-Marco D, Modolell J Araucan and caupolican, two members of the novel iroquois complex, encode homeoproteins that control proneural and vein-forming genes. Cell. 1996;85:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardeña-Núñez S, Sánchez-Guardado LÓ, Corral-San-Miguel R, Rodríguez-Gallardo L, Marín F, Puelles L, Aroca P, Hidalgo-Sánchez M. Expression patterns of Irx genes in the developing chick inner ear. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:2071–2092. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee K, Bu ¨rglin TR. Comprehensive analysis of animal TALE homeobox genes: new conserved motifs and cases of accelerated evolution. J Mol Evol. 2007;65:137–153. doi: 10.1007/s00239-006-0023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerner P, Ikmi A, Coen D, Vervoort M. Evolutionary history of the iroquois/Irx genes in metazoans. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larroux C, Luke GN, Koopman P, Rokhsar DS, Shimeld SM, Degnan BM. Genesis and expansion of metazoan transcription factor gene classes. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:980–996. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters T, Dildrop R, Ausmeier K, Ruther U. Organization of mouse Iroquois homeobox genes in two clusters suggests a conserved regulation and function in vertebrate development. Genome Res. 2000;10:1453–1462. doi: 10.1101/gr.144100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogura K, Matsumoto K, Kuroiwa A, Isobe T, Otoguro T, Jurecic V, Baldini A, Matsuda Y, Ogura T. Cloning and chromosome mapping of human and chicken Iroquois (IRX) genes. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;92:320–325. doi: 10.1159/000056921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez-Skarmeta JL, and Modolell J Iroquois genes: genomic organization and function in vertebrate neural development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:403–408. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houweling AC, Dildrop R, Peters T, Mummenhoff J, Moorman AF, Ruther U, Christoffels VM. Gene and cluster-specific expression of the Iroquois family members during mouse development. Mech Dev. 2001;107:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorgensen JS, Gao L. Irx3 is differentially up-regulated in female gonads during sex determination. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5:756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebel M, Agarwal P, Cheng CW, Kabir MG, Chan TY, Thanabalas- ingham V, Zhang X, Cohen DR, Husain M, Cheng SH. The Iroquois homeobox gene Irx2 is not essential for normal development of the heart and midbrain- hindbrain boundary in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8216–8225. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8216-8225.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao ZZ, Bruneau BG, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Cepko CL. Regulation of chamber-specific gene expression in the developing heart by Irx4. Science. 1999;283:1161–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker MB, Zulch A, Bosse A, Gruss P. Irx1 and Irx2 expression in early lung development. Mech Dev. 2001;106:155–168. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Zhang J, Liu L, Jiang Y, Ji J, Yan R, Zhu Z, Yingyan Y. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5-mediated epigenetic silencing of IRX1 contributes to tumorigenicity and metastasis of gastric cancer molecular basis of disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:2835–2844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang P, Liu N, Xu X, Wang Z, Cheng Y, Jing W, Wang X, Yang H, Liu H, Zhang Y. Clinical significance of Iroquois homeobox gene IRX1 in human glioma. Mol Med Reports. 2018;17:4651–4656. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo X, Liu W, Pan Y, Ni P, Ji J, Guo L, Zhang J, Wu J, Jiang J, Chen X. Homeobox gene IRX1 is a tumor suppressor gene in gastric carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:3908–3920. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett KL, Karpenko M, Lin M, Claus R, Arab K, Dyckhoff G, Plinkert P, Herpel E, Smiraglia D, Plass C. Frequently methylated tumor suppressor genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(12):4494–4499. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis MT, Ross S, Strickland PA, Snyder CJ, Daniel CW. Regulated expression patterns of IRX-2, an Iroquois-class homeo- box gene, in the human breast. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:549–554. doi: 10.1007/s004410051316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asaka S, Fujimoto T, Akaishi J, Ogawa K, Onda M. Genetic prognostic index influences patient outcome for node-positive breast cancer. Surg Today. 2006;36:793–801. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupret B, Völkel P, Follet P, Bourhis XL, Angrand PO. Combining genotypic and phenotypic analyses on single mutant zebrafish larvae. Methods X. 2018;5:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung IH, Chung YY, Jung DE, Kim YJ, Kim DH, Kim KS, Park SW. Impaired lymphocytes development and xenotransplantation of gastrointestinal tumor cells in Prkdc-Null SCID zebrafish model. Neoplasia. 2016;18(8):468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1555–1577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saeed A.I., Sharov V., White J., Li J., Liang W., Bhagabati N., Braisted J., Klapa M., Currier T., Thiagarajan M. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park SW, Davison JM, Rhee J, Hruban RH, Maitra A, Leach SD. Oncogenic KRAS induces progenitor cell expansion and malignant transformation in zebrafish exocrine pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:2080–2090. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu J, Song G, Tang Q, Zou C, Han F, Zhao Z, Yong B, Yin J, Xu H, Xie X. IRX1 hypomethlyation promotes osteosarcoma metastasis via induction of CXCL14/NF-κB signaling. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):1839–1856. doi: 10.1172/JCI78437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng CW, Hui C, Strahle U, Cheng SH. Identification and expression of zebrafish Iroquois homeobox gene irx1. Dev Genes Evol. 2001;211(8–9):442–444. doi: 10.1007/s004270100168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regneri J, Klotz B, Wilde B, Kottler VA, Hausmann M, Kneitz S, Regensburger M, Maurus K, Götz R, Lu Y. Analysis of the putative tumor suppressor gene cdkn2ab in pigment cells and melanoma of Xiphophorus and medaka. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2019;32(2):248–258. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liggett WH, Jr., Sidransky D. Role of the p16 tumor suppressor gene in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(3):1197–1206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banasavadi-Siddegowda YK, Russell I, Frair E, Karkhanis VA, Relation T, Yoo JY, Zhang J, Sif S, Imitola J, Baiocchi R. PRMT5-PTEN molecular pathway regulates senescense and self-renewal of primary glioblastoma neurophere cells. Oncogene. 2017;36:263–274. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables