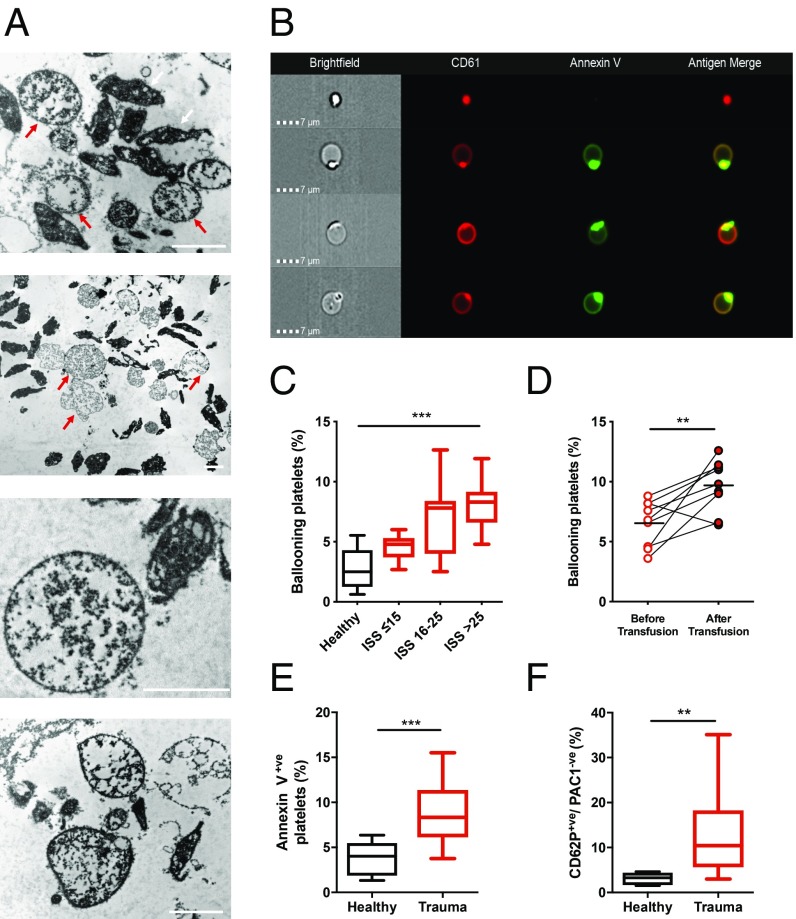

Fig. 2.

Platelet ballooning during trauma hemorrhage. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy images of platelet-rich plasma from 3 patients with severe injuries showing ballooning platelets (red arrows) with loss of membrane integrity and absent cytoplasmic contents. White arrows indicate nonballooned platelets. (Scale bars, 2 µm.) (B) Representative images from trauma patients demonstrating a morphologically normal platelet (Top) and platelets displaying membrane ballooning and annexin V binding. (C) Number of ballooning platelets in healthy volunteers (black, n = 10) and in trauma patients (red) with mild–moderate injuries (ISS ≤ 15, n = 13), severe injuries (ISS 16–25, n = 17), and critical injuries (ISS > 25, n = 18). Results expressed as proportion of platelets. Box plots display median with interquartile range and 10th–90th percentiles. ***P < 0.01, 1-way ANOVA. (D) Level of ballooning before (pre-) and after (post-) platelet transfusion in serial samples taken during active hemorrhage (n = 9). Lines indicate mean. **P < 0.01, paired t test. (E) Annexin V binding to platelets isolated from healthy volunteers (n = 8) and trauma patients (n = 18). ***P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test. (F) Frequency of P-selectin+ve/PAC-1−ve platelets in healthy volunteers (n = 8) and trauma patients (n = 28). **P < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U test.